Race, Transportation, and the Future of Metropolitan Atlanta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Atlanta Preservation Center's

THE ATLANTA PRESERVATION CENTER’S Phoenix2017 Flies A CELEBRATION OF ATLANTA’S HISTORIC SITES FREE CITY-WIDE EVENTS PRESERVEATLANTA.COM Welcome to Phoenix Flies ust as the Grant Mansion, the home of the Atlanta Preservation Center, was being constructed in the mid-1850s, the idea of historic preservation in America was being formulated. It was the invention of women, specifically, the ladies who came J together to preserve George Washington’s Mount Vernon. The motives behind their efforts were rich and complicated and they sought nothing less than to exemplify American character and to illustrate a national identity. In the ensuing decades examples of historic preservation emerged along with the expanding roles for women in American life: The Ladies Hermitage Association in Nashville, Stratford in Virginia, the D.A.R., and the Colonial Dames all promoted preservation as a mission and as vehicles for teaching contributive citizenship. The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition held in Piedmont Park here in Atlanta featured not only the first Pavilion in an international fair to be designed by a woman architect, but also a Colonial Kitchen and exhibits of historic artifacts as well as the promotion of education and the arts. Women were leaders in the nurture of the arts to enrich American culture. Here in Atlanta they were a force in the establishment of the Opera, Ballet, and Visual arts. Early efforts to preserve old Atlanta, such as the Leyden Columns and the Wren’s Nest were the initiatives of women. The Atlanta Preservation Center, founded in 1979, was championed by the Junior League and headed by Eileen Rhea Brown. -

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary ................................................................5 Summary of Resources ...........................................................6 Regionally Important Resources Map ................................12 Introduction ...........................................................................13 Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value .................21 Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ..................................48 Areas of Scenic and Agricultural Value ..............................79 Appendix Cover Photo: Sope Creek Ruins - Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area/ Credit: ARC Tables Table 1: Regionally Important Resources Value Matrix ..19 Table 2: Regionally Important Resources Vulnerability Matrix ......................................................................................20 Table 3: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ...........46 Table 4: General Policies and Protection Measures for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ................47 Table 5: National Register of Historic Places Districts Listed by County ....................................................................54 Table 6: National Register of Historic Places Individually Listed by County ....................................................................57 Table 7: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ............................77 Table 8: General Policies -

Raise the Curtain

JAN-FEB 2016 THEAtlanta OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE OF AtLANTA CoNVENTI ON &Now VISITORS BUREAU ATLANTA.NET RAISE THE CURTAIN THE NEW YEAR USHERS IN EXCITING NEW ADDITIONS TO SOME OF AtLANTA’S FAVORITE ATTRACTIONS INCLUDING THE WORLDS OF PUPPETRY MUSEUM AT CENTER FOR PUPPETRY ARTS. B ARGAIN BITES SEE PAGE 24 V ALENTINE’S DAY GIFT GUIDE SEE PAGE 32 SOP RTS CENTRAL SEE PAGE 36 ATLANTA’S MUST-SEA ATTRACTION. In 2015, Georgia Aquarium won the TripAdvisor Travelers’ Choice award as the #1 aquarium in the U.S. Don’t miss this amazing attraction while you’re here in Atlanta. For one low price, you’ll see all the exhibits and shows, and you’ll get a special discount when you book online. Plan your visit today at GeorgiaAquarium.org | 404.581.4000 | Georgia Aquarium is a not-for-profit organization, inspiring awareness and conservation of aquatic animals. F ATLANTA JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2016 O CONTENTS en’s museum DR D CHIL ENE OP E Y R NEWL THE 6 CALENDAR 36 SPORTS OF EVENTS SPORTS CENTRAL 14 Our hottest picks for Start the year with NASCAR, January and February’s basketball and more. what’S new events 38 ARC AROUND 11 INSIDER INFO THE PARK AT our Tips, conventions, discounts Centennial Olympic Park on tickets and visitor anchors a walkable ring of ATTRACTIONS information booth locations. some of the city’s best- It’s all here. known attractions. Think you’ve already seen most of the city’s top visitor 12 NEIGHBORHOODS 39 RESOURCE Explore our neighborhoods GUIDE venues? Update your bucket and find the perfect fit for Attractions, restaurants, list with these new and improved your interests, plus special venues, services and events in each ’hood. -

Atlanta's Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class

“To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 by William Seth LaShier B.A. in History, May 2009, St. Mary’s College of Maryland A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Eric Arnesen James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that William Seth LaShier has passed the Final Examinations for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 20, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 William Seth LaShier Dissertation Research Committee Eric Arnesen, James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History, Dissertation Director Erin Chapman, Associate Professor of History and of Women’s Studies, Committee Member Gordon Mantler, Associate Professor of Writing and of History, Committee Member ii Acknowledgements I could not have completed this dissertation without the generous support of teachers, colleagues, archivists, friends, and most importantly family. I want to thank The George Washington University for funding that supported my studies, research, and writing. I gratefully benefited from external research funding from the Southern Labor Archives at Georgia State University and the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Books Library (MARBL) at Emory University. -

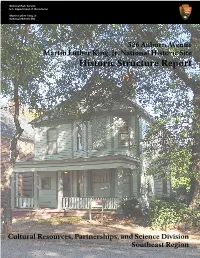

Historic Structure Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science Division Southeast Region 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report May 2017 Prepared by: WLA Studio SBC+H Architects Palmer Engineering Under the direction of National Park Service Southeast Regional Offi ce Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division The report presented here exists in two formats. A printed version is available for study at the park, the Southeastern Regional Offi ce of the National Park Service, and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, this report also exists in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps. gov for more information. Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division Southeast Regional Offi ce National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404)507-5847 Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 450 Auburn Avenue, NE Atlanta, GA 30312 www.nps.gov/malu About the cover: View of 526 Auburn Avenue, 2016. 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Approved By : Superintendent, Date Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Recommended By : Chief, Cultural Resource, Partnerships & Science Division Date Southeast Region Recommended By : Deputy Regional Director, -

Fire Station No. 6 Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church and School

North FREEDOM PARKWAY To Carter Center 0 20 100 Meters From Freedom Parkway, turn south onto Boulevard 0 100 500 Feet and follow signs to parking lot. Cain Street Boulevard John Wesley Dobbs Avenue International Boulevard Parking lot John Wesley Dobbsentrance Avenue Butler Street Exit Ellis Street NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE BOUNDARY PRESERVATION DISTRICT BOUNDARY PARKING John Wesley Dobbs Avenue Irwin Street Irwin Street Butler Street Courtland Street Piedmont Avenue Big Bethel African National Park Service Alexander Hamilton, Jr., Methodist Episcopal Visitor Center Home 450 Auburn Ave. The visitor center 102 Howell St. Built 1890-95. This Church Fort Street has exhibits, a video program, and elegant house, whose architectural Hilliard Street John Wesley Dobbs Avenue 220 Auburn Ave. Built 1890s; re- Hogue Street built 1924. The church’s most prom- a schedule of park activities. details include a Palladian window Rucker Building National Park Service personnel and Corinthian columns, was home 158-60 Auburn Ave. Completed inent feature, the “Jesus Saves” sign on the steeple, was added when provide information and answer to Atlanta’s leading black building Atlanta Life Insurance 1904. Atlanta’s first black office questions. contractor in the early 1900s. building was constructed by busi- the structure was rebuilt after a Double “Shotgun” Company Building PROMENADE nessman and politician Henry A. 1920 fire. Row Houses 148 Auburn Ave. Completed 1920; Rucker. The King Center annex (142 Auburn) built 1936. From The Martin Luther King, Jr., Center 472-488 Auburn Ave. Built in 1905 Prince Hall Masonic for Empire Textile Company mill 1920 to 1980, this was the head- for Nonviolent Social Change, Inc., Jackson Street quarters of the country’s largest workers. -

Black History Itinerary

Black History Tour Tour Length: Half Day (4hrs) Number of Stops to explore: 2-3 Tour allows time to take photos and explore on your own Downtown Atlanta • Olympic Torch & Olympic Rings • Olympic Stadium & Turner Field & Fulton County Stadium • Fulton Court House & Government Center • Atlanta City Hall • Georgia State Capitol Building • Underground Atlanta • Mercedes Benz Dome/Phillips Arena/CNN Center • Famous TV/Movie Locations • Woodruff Park Historic West End (Atlanta’s Oldest Neighborhood) • Tyler Perry Studios/Famous Madea House • West End Historic Homes • The Wren's Nest • Historic West Hunter Baptist Church • Hammond House & Museum • Willie Watkins Funeral Home • Shrine Of The Black Madonna Bookstore & Culture Center • HBCU (Atlanta University Center) Vine City (One of Atlanta’s Oldest Black Neighborhoods) • Charles A. Harper Park • Washington Park (Atlanta’s 1st Black City Park) • Booker T. Washington High School (Atlanta’s 1st Black Public High School) • Martin Luther King Jr, Drive (2nd Major Black Atlanta Avenue of Black Businesses) • Paschal's Restaurant and Hotel (Civil Rights Headquarters/Black City Hall) • Busy Bee’s Soul Food Restaurant • Historic Sunset Avenue Neighborhood (Civil Rights Foot Soldiers Residence) • Historic Herndon Home Mansion & Museum • Historic Friendship Baptist Church Historic Castleberry Hills • New Paschal’s Restaurant & H.J. Russell Headquarters • Castleberry Hill Mural Wall • Old Lady Gang Restaurant (RHOA Kandi Burress) • Famous Movie Location Sweet Auburn Avenue (Atlanta’s Most famous Black Neighborhood) • Mary Combs • Atlanta Daily World • Atlanta Life Insurance • The APEX Museum • The Royal Peacock • Historic Big Bethel A.M.E Church • Hanley’s Funeral Home/Auburn Curb Market • Famous TV/Movie Locations • Historic Wheat Street Baptist • SCLC Headquarters/W.E.R.D Radio/Madam CJ Walker Museum • The King Center/Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church/Birth Home/Fire Station #6 Black History Tour . -

Downtown Atlanta Available Sites

Downtown Atlanta Available Sites CURRENTLY ON THE MARKET South Downtown 1. Ted Turner Drive at Whitehall Street – Artisan Yards Atlanta, GA 30303 Multi-parcel assemblage under single ownership 9.86 AC (429,502 SF) lot Contact: Bruce Gallman at [email protected] 2. 175-181 Peachtree St SW - Vacant Land/Parking Lot Land of 0.25 AC. Site adjoins Garnett MARTA Station, for sale, lease, or will develop, key corner with 110" frontage on Peachtree St. and 100' frontage on Trinity Ave. For sale at $2,240,000 ($8,712,563/AC) John Paris, Paris Properties at (404) 763-4411 and [email protected] 3. Broad St/Mitchell Street Assemblage 111 Broad Street, SW, Atlanta, GA 30303 (3,648 s.f.) 115 Broad Street, SW, Atlanta, GA 30303 (3,072 s.f.) 185 Mitchell Street, SW, Atlanta, GA 30303 (5,228 s.f.) Parking Lot on Mitchell Street, SW - Between 185 & 191 Mitchell Street 191 Mitchell Street, SW, Atlanta, GA. 30303 (2,645 s.f.) For sale at $3.6 million Contact Dave Aynes, Broker / Investor, (404) 348-4448 X2 (p) or [email protected] 4. 207-211 Peachtree St Atlanta, GA For Sale at $1,050,000 ($35.02/SF) 29,986 SF Retail Freestanding Building Built in 1915 Contact: Herbert Greene, Jr. (404) 589-3599 (p) or [email protected] 5. 196 Peachtree Street Atlanta, GA 19,471 SF Retail Storefront Retail/Office Building Built in 1970 For Sale at $5 million ($256.79/SF) Contact: Herbert Greene, Jr. (404) 589-3599 (p) or [email protected] 6. -

Phoenix Flies Program3.Indd

Phoenix Flies A Citywide Celebration of Living Landmarks March 5-20, 2011 More than 150 FREE events throughout Atlanta www.PhoenixFlies.org About The Phoenix Flies he phoenix is a mythical, flying creature that is born from the ashes of its own incineration. Like this powerful creature, so too was Atlanta reborn from her ashes. The phoenix has been a part of Atlanta’s seal and served as her symbol since 1887. In creat- March 2011 Ting a celebration of Atlanta’s living historic fabric, The Atlanta Preservation Dear Friends of Phoenix Flies, Center again looked to this magical creature. The Phoenix Flies: A Celebration of Living Landmarks was created in 2003 by Our City is the product of the efforts of those who have gone before us The Atlanta Preservation Center as a way to celebrate the 25th anniversary and those who make the successes of today stand on their shoulders. of the dramatic rescue of the Fox Theatre, an event that changed Atlanta’s Atlanta is rich with the evidence of this continuing process, from the preservation outlook forever. Since that time surviving names on our original street grid of the mid-19th century to the Modernist architecture of the 1960s, we have much material This March and the celebration has won an Award of Excel- that illustrates the various epochs in the life of our city. The Atlanta in the following lence from the Atlanta Urban Design Com- Preservation Center, through its mission of preserving Atlanta’s historic mission, a Preservation Award from the Geor- and culturally significant buildings, neighborhoods and landscapes, has months take time gia Trust for Historic Preservation, presented been dedicated through advocacy and education to the survival and to explore what over 1,000 events and provided a better un- celebration of this heritage. -

Atlanta Heritage Trails 2.3 Miles, Easy–Moderate

4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks 4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks A Comprehensive Guide to Walking, Running, and Bicycling the Area’s Scenic and Historic Locales Ren and Helen Davis Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Copyright © 1988, 1993, 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All photos © 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without prior permission of the publisher. This book is a revised edition of Atlanta’s Urban Trails.Vol. 1, City Tours.Vol. 2, Country Tours. Atlanta: Susan Hunter Publishing, 1988. Maps by Twin Studios and XNR Productions Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Cover design by Maureen Withee Composition by Robin Sherman Fourth Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Manufactured in August 2011 in Harrisonburg, Virgina, by RR Donnelley & Sons in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Davis, Ren, 1951- Atlanta walks : a comprehensive guide to walking, running, and bicycling the area’s scenic and historic locales / written by Ren and Helen Davis. -- 4th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56145-584-3 (alk. paper) 1. Atlanta (Ga.)--Tours. 2. Atlanta Region (Ga.)--Tours. 3. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta-- Guidebooks. 4. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta Region--Guidebooks. 5. -

Curriculum Guide: the President's Travels

Curriculum Guide: The President’s Travels Unit 2 of 19: Life in Plains, Georgia 441 Freedom Parkway, Atlanta, GA, 30312 | 404-865-7100 | www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov Life in Plains Kindergarten GPS: SSKH3: Correctly use words and phrases related to chronology and time to explain how things change. Second Grade GPS: SS2H1a: Identify contributions made by Jimmy Carter (leadership and human rights) and Dr. Martin The Man from Plains Luther King, Jr. (civil rights). President Jimmy Carter was born in Plains, Georgia, in 1924. A few SS2H2b: Describe how the everyday life of this historical years later, President Carter’s family moved from Plains to the figure is similar to and different nearby rural community of Archery. The Carter family farmed, and from everyday life in the present. leased some of its land to African-American sharecroppers. Because SS2G2: Describe the cultural and President Carter’s mother was often busy as a nurse, and his father geographic systems associated worked long hours in the fields, young President Carter spent much with the historical figures in of his time with his African-American neighbors. SS2H1. SS2CG2a,b: Identify the roles of President Carter cites these early experiences in Archery as pivotal the following elected officials – in his development as a person and as a leader. He also cherishes his President and Governor. eleven years of education at Plains High School (Grades 1-11), even quoting his teacher and principal, Miss Julia Coleman, in his Third Grade Inaugural Address. GPS: After graduating from Plains High School, President Carter attended Georgia Southwestern College, the Georgia Institute of Technology, and graduated from the United States Naval Academy SS3H2a: Discuss the lives of in Annapolis, Maryland. -

Viagra Purchase Canada

Downtown Atlanta Contemporary Historic Resources Survey Master Spreadsheet--Contains all parcels meeting the survey criteria by Atlanta Preservation & Planning Services, LLC; Karen Huebner; Morrison Design, LLC, September 2013 GNAHRGIS Street Year Built NR COA Designated ID Number Number Street Name Location Information Building Name(s)-oldest first Parcel ID Year Built Decade Building Type Architectural Style Original Use CurrentUse Levels Notes Eligibility NR Individually Listed NR Historic District COA Designated District Building City State Zip County East of Forsyth Street; aka 143 Finch-Heery; Vincent Kling (Philadelphia) design 243986 30 ALABAMA ST SW Alabama Five Points MARTA Station 14 007700020668 1979 1970-1979 Rapid Transit Station Late Modern Rapid Transit Station Rapid Transit Station 2 consultant to MARTA No Atlanta GA 30303 Fulton 1901 Eiseman Building Façade Architectural Façade Beaux Arts Architectural Façade 243987 30 ALABAMA ST SW Five Points MARTA Station Elements 14 007700020668-X 1979 1970-1979 Elements Classicism Elements Work of Art N/A Walter T. Downing No Atlanta GA 30303 Fulton Atlanta Constitution Building; Georgia Power Atlanta Division 243159 143 ALABAMA ST SW West of Forsyth Street Building 14 007700020650 1947 1940-1949 Commercial Block Streamline Moderne Professional/Office Professional/Office 5 Robert & Co. Yes Atlanta GA 30303 Fulton ANDREW YOUNG INTL BLVD Commercial Plain 243652 17 NE Good Food Building 14 005100040229 ca. 1935 1935-1939 Commercial Block Style Unknown Restaurant/Bar 2 Maybe Atlanta