Jrnuhl00fren.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hay Any Work for Cooper 1 ______

MARPRELATE TRACTS: HAY ANY WORK FOR COOPER 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ Hay Any Work For Cooper.1 Or a brief pistle directed by way of an hublication2 to the reverend bishops, counselling them if they will needs be barrelled up3 for fear of smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state, that they would use the advice of reverend Martin for the providing of their cooper. Because the reverend T.C.4 (by which mystical5 letters is understood either the bouncing parson of East Meon,6 or Tom Cook's chaplain)7 hath showed himself in his late Admonition To The People Of England to be an unskilful and beceitful8 tub-trimmer.9 Wherein worthy Martin quits himself like a man, I warrant you, in the modest defence of his self and his learned pistles, and makes the Cooper's hoops10 to fly off and the bishops' tubs11 to leak out of all cry.12 Penned and compiled by Martin the metropolitan. Printed in Europe13 not far from some of the bouncing priests. 1 Cooper: A craftsman who makes and repairs wooden vessels formed of staves and hoops, as casks, buckets, tubs. (OED, p.421) The London street cry ‘Hay any work for cooper’ provided Martin with a pun on Thomas Cooper's surname, which Martin expands on in the next two paragraphs with references to hubs’, ‘barrelling up’, ‘tub-trimmer’, ‘hoops’, ‘leaking tubs’, etc. 2 Hub: The central solid part of a wheel; the nave. (OED, p.993) 3 A commodity commonly ‘barrelled-up’ in Elizabethan England was herring, which probably explains Martin's reference to ‘smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state’. -

In the Foreign Legion

In the Foreign Legion by Erwin Rosen, 1876-1923 Published: 1910 Duckworth & Co., London J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Prologue & Chapter I … Legionnaire! In Belfort : Sunrays and fear : Madame and the waiter : The French lieutenant : The enlistment office of the Foreign Legion : Naked humanity : A surgeon with a lost sense of smell : „Officier Allemand“ : My new comrades : The lieutenant-colonel : A night of tears. Chapter II … L‘Afrique. Transport of recruits on the railway : What our ticket did for us and France : The patriotic conductor : Marseilles : The gate of the French Colonies : The Colonial hotel : A study in blue and yellow : On the Mediterranean : The ship‘s cook : The story of the Royal Prince of Prussia at Saida : Oran : Wine and légionnaires : How the deserter reached Spain and why he returned. Chapter III … Légionnaire Number 17889. French and American bugle-calls : Southward to the city of the Foreign Legion : Sidi-bel-Abbès : The sergeant is not pleased : A final fight with pride : The jokes of the Legion : The wise negro : Bugler Smith : I help a légionnaire to desert : The Eleventh Company : How clothes are sold in the Legion : Number 17889. Chapter IV … The Foreign Legion‘s Barracks. In the company‘s storeroom : Mr. Smith—American, légionnaire, philosopher : The Legion‘s neatness : The favourite substantive of the Foreign Legion : What the commander of the Old Guard said at Waterloo : Old and young légionnaires : The canteen : Madame la Cantinière : The regimental feast : Strange men and strange things : The skull : The prisoners‘ march : The wealth of Monsieur Rassedin, légionnaire : „Rehabilitation“ : The Koran chapter of the Stallions. -

Uniforms and Armies of Bygone Days Year 3

Uniforms and Armies of bygone days Year 3 – No. 9 Contents P.1 The Campaign of 1807 M. Göddert P.7 Questions and Answers P.9 Russian Dragoons 1807 M. Stein Plate 1 E. Wagner P.18 The Municipal Guard of Paris M. Gärtner Plates 2-3 P.29 Royal Württemberg Military 1806-1808 U. Ehmke Plate 4 Unless otherwise noted, the drawings interspersed throughout the text are by G. Bauer and R. Knötel. Editor Markus Stein 2020 translation: Justin Howard i Introduction First of all, I would like to convey my thanks for the kind letters, sent in reply to my circular, in which many readers expressed understanding for the delay to this issue. In fact, two issues – the result of a year’s work – are now being published simultaneously and, as announced, the focus in this issue as well as part of the next one will be on the Campaign of 1807, which is now 180 years ago. This campaign, or rather its consequences, brought Napoleon I to the summit of his turbulent career, because France was then faced only by its arch-enemy England, and its sphere of power and influence had reached its greatest extent. But at what price! As early as the Winter Campaign of 1806/07, first major weak points had become apparent in Napoleon’s method of conducting warfare, for example the French army and corps commanders’ lack of strategic and tactical training. Significant flaws also manifested themselves in the French supply system, which was based almost exclusively on the requisition and purchasing of stocks and goods in the occupied enemy country – difficult to achieve in the impoverished and, moreover, wintry Poland. -

Sault Tribe Receives $2.5M Federal HHS Grant Tribe Gets $1.63 Million

In this issue Recovery Walk, Pages 14-15 Tapawingo Farms, Page 10 Squires 50th Reunion, Page 17 Ashmun Creek, Page 23 Bnakwe Giizis • Falling Leaves Moon October 7 • Vol. 32 No. 10 Win AwenenOfficial newspaper of the SaultNisitotung Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians Sault Tribe receives $2.5M federal HHS grant The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of diseases such as diabetes, heart tobacco-free living, active living blood pressure and high choles- visit www.healthysaulttribe.net. Chippewa Indians is one of 61 disease, stroke and cancer. This and healthy eating and evidence- terol. Those wanting to learn more communities selected to receive funding is available under the based quality clinical and other To learn more about Sault Ste. about Community Transformation funding in order to address tobac- Affordable Care Act to improve preventive services, specifically Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians’ Grants, visit www.cdc.gov/com- co free living, active and healthy health in states and communities prevention and control of high prevention and wellness projects, munitytransformation. living, and increased use of high and control health care spending. impact quality clinical preventa- Over 20 percent of grant funds tive services across the tribe’s will be directed to rural and fron- seven-county service area. The tier areas. The grants are expected U.S. Department of Health and to run for five years, with projects Human Services announced the expanding their scope and reach grants Sept. 27. over time as resources permit. The tribe’s Community Health According to Hillman, the Sault Department will receive $2.5 mil- Tribe’s grant project will include lion or $500,000 annually for five working with partner communities years. -

Inside Facts of Stage and Screen (February 7, 1931)

STAGE PRICE lO CENTS RADIO SCREEN Only Theatrical MUSIC Newspaper on the Pacific Coast j EDITED BY JACK JOSEPHS ESTABLISHED 1924 Entered Vol. XIII as Second Class Matter, April 29, 1927, at Post- office, Los. Angeles, Calif., Published Every Saturday at 809 Warner Bros Down- under Act ’ Saturday, of March 3, 1879 February 7, 1931 town Building. 401 West Seventh St., Los Angeles, Calif. No. 5 PLAN ‘JITNEY THEATRE’ CHAIN FOR PAC. COAST +- Press and MX Group Show Biz To Finance In Clash 10c Houses ' A war which has been , brewing leaf theatre ween local interests and A chain of miniature theatres, of the local press was all set to break two hundred seating capacity and oqt in dead earnest this week. to operate on a 10 cents admission Illustrated The Los Angeles schedule, is planned by a Nip-tY. -"k Daily, News, a morning- tabloid, orgr’fization which ha? fired broadside • • a into show busi- sodufcs on the toa-on. ove ness under a five-column line on prospects for nikiatiiifc Jha.., of page 2 their Thursday editions, here. panning the gala premiere policy to a fare-ye-well. While the News The plan is to spot the houses in shot was particularly at the pre- class picture neighborhoods, play- miere of RKO’s “Cimarron” at the ing opposition to the 65 centers and Orpheum Theatre, it was a crack relying for their draw on the smaii at the whole premiere practice. admission fee. ' Info from inside the battle lines, The program will be a feature, a coupled up with the fact that the comedy and a newsreel. -

These Strange Criminals: an Anthology Of

‘THESE STRANGE CRIMINALS’: AN ANTHOLOGY OF PRISON MEMOIRS BY CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS FROM THE GREAT WAR TO THE COLD WAR In many modern wars, there have been those who have chosen not to fight. Be it for religious or moral reasons, some men and women have found no justification for breaking their conscientious objection to vio- lence. In many cases, this objection has lead to severe punishment at the hands of their own governments, usually lengthy prison terms. Peter Brock brings the voices of imprisoned conscientious objectors to the fore in ‘These Strange Criminals.’ This important and thought-provoking anthology consists of thirty prison memoirs by conscientious objectors to military service, drawn from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and centring on their jail experiences during the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War. Voices from history – like those of Stephen Hobhouse, Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, Ian Hamilton, Alfred Hassler, and Donald Wetzel – come alive, detailing the impact of prison life and offering unique perspectives on wartime government policies of conscription and imprisonment. Sometimes intensely mov- ing, and often inspiring, these memoirs show that in some cases, indi- vidual conscientious objectors – many well-educated and politically aware – sought to reform the penal system from within either by publicizing its dysfunction or through further resistance to authority. The collection is an essential contribution to our understanding of criminology and the history of pacifism, and represents a valuable addition to prison literature. peter brock is a professor emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Toronto. -

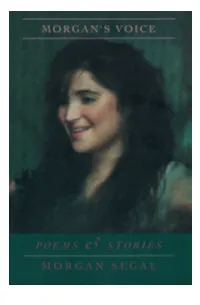

Get a PDF Copy of Morgan's Voice

Morgan's Voice POEMS& STORIES Morgan Segal Copyright © 1997 by RobertSegal All rights reserved. Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data Segal,Morgan Morgan's Voice Poems8c Stories ISBN 0-9662027-0-8 First Edition 1997 Designedby RileySmith Printed in the United Statesof America by PacificRim Printers/Mailers 11924 W. Washington Blvd. LosAngeles, CA 90066 Printed on acid-free, recycled paper. The gift of sharing so intimately in Morgan's life, through her prose and poetry, is one all will commit to their hearts. Here are remembrances, emotionally inspired, of personal journeys through a landscape of experience that has been both tranquil and turbulent. Her poems are "pearls dancing," shimmering like her own life in an all too brief sunlight; her stories portraits, at times fragile, at times triumphant in their will to witness lasting humaness. She is tmly a talent and a presence too soon lost. -James Ragan, Poet Director, Professional Writing Program University of Southern California Morgan possessed a rare and beautiful soul. Those wide brown eyes of hers shone forth with a child's curiosity and innocence. But her heart was the heart of woman who was haunted by unfathomable darkness. Morgan's words are infused with depth, wisdom, honesty, courage and insight. Her descriptions reveal the intense thirst she had for even the most mundane aspects of life -- a fingernail, the scale of a fish, a grandfather's breath, a strand of hair. The attention she pays to details can help us to return to our lives with a renewed revereance for all the subtle miracles that surround us each moment. -

Ellis & Associates, Inc

INTERNATIONAL LIFEGUARD Training Program Manual 5th Edition Meets ECC, MAHC, and OSHA Guidelines Ellis & Associates, Inc. 5979 Vineland Rd. Suite 105 Orlando, FL 32819 www.jellis.com 800-742-8720 Copyright © 2020 by Ellis & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated in writing by Ellis & Associates, the recipient of this manual is granted the limited right to download, print, photocopy, and use the electronic materials to fulfill Ellis & Associates lifeguard courses, subject to the following restrictions: • The recipient is prohibited from downloading the materials for use on their own website. • The recipient cannot sell electronic versions of the materials. • The recipient cannot revise, alter, adapt, or modify the materials. • The recipient cannot create derivative works incorporating, in part or in whole, any content of the materials. For permission requests, write to Ellis & Associates, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address above. Disclaimer: The procedures and protocols presented in this manual and the course are based on the most current recommendations of responsible medical sources, including the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) Consensus Guidelines for CPR, Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) and First Aid, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards 1910.151, and the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC). The materials have been reviewed by internal and external field experts and verified to be consistent with the most current guidelines and standards. Ellis & Associates, however, make no guarantee as to, and assume no responsibility for, the correctness, sufficiency, or completeness of such recommendations or information. Additional procedures may be required under particular circumstances. Ellis & Associates disclaims all liability for damages of any kind arising from the use of, reference to, reliance on, or performance based on such information. -

MEMOIRS of the Royal Artillery Band

TARY M Bfc_ IN ENGLAND ^^B ww <::,>„ /.:' FARMER / /^Vi^i^ 1 *^ '" s S^iii , ~H! ^ **- foH^^ St5* f 1 m £*2i pH *P**" mi * i Ilia TUTu* t W* i L« JW-Rj fA 41U fit* .1? ' ^fl***-* vljjj w?tttai". m~ lift 1 A w rf'Jls jftt » Ijg «Hri ». 4 Imj v .*<-» *)i4bpt=? ..... y MEMOIRS OF THE Royal Artillery Band ITS ORIGIN, HISTORY AND PROGRESS An Account of the Rise of Military Music in England HENRY GEORGE FARMER Bombardier, Royal Artillery Band " 1 am beholden to you for your sweet music —PERICLES WITH 14 ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON BOOSEY & CO., 295, REGENT STREET AND NEW YORK 1904 TO THE OFFICERS OF THE ROYAL REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY THIS HISTORY OF THEIR REGIMENTAL BAND IS BY PERMISSION MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/memoirsofroyalarOOfarm —; PREFACE. " Now, instead of going on denying that we are an unmusical nation, let us do our utmost to prove that we are a musical nation."—SIR ALEX. MACKENZIE. " A History of British Military Music is much needed." So said the Musical Times some six or seven years ago and to-day, when military music and military bands are so much discussed, a work of this kind appears to be urgently called for. This volume, however, makes no pretence whatever to supply the want, but merely claims to be a history of one of the famous bands in the service, that of the Royal Artillery. The records of this band date as far back as 1762, when it was formed, and I doubt if there is another band in the army with a continuous history for so long a period. -

The Passion of Max Von Oppenheim Archaeology and Intrigue in the Middle East from Wilhelm II to Hitler

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/163 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Lionel Gossman is M. Taylor Pyne Professor of Romance Languages (Emeritus) at Princeton University. Most of his work has been on seventeenth and eighteenth-century French literature, nineteenth-century European cultural history, and the theory and practice of historiography. His publications include Men and Masks: A Study of Molière; Medievalism and the Ideologies of the Enlightenment: The World and Work of La Curne de Sainte- Palaye; French Society and Culture: Background for 18th Century Literature; Augustin Thierry and Liberal Historiography; The Empire Unpossess’d: An Essay on Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall”; Between History and Literature; Basel in the Age of Burckhardt: A Study in Unseasonable Ideas; The Making of a Romantic Icon: The Religious Context of Friedrich Overbeck’s “Italia und Germania”; Figuring History; and several edited volumes: The Charles Sanders Peirce Symposium on Semiotics and the Arts; Building a Profession: Autobiographical Perspectives on the Beginnings of Comparative Literature in the United States (with Mihai Spariosu); Geneva-Zurich-Basel: History, Culture, and National Identity, and Begegnungen mit Jacob Burckhardt (with Andreas Cesana). He is also the author of Brownshirt Princess: A Study of the ‘Nazi Conscience’, and the editor and translator of The End and the Beginning: The Book of My Life by Hermynia Zur Mühlen, both published by OBP. -

Claremen Who Fought in the Battle of the Somme July-November 1916

ClaremenClaremen who who Fought Fought in The in Battle The of the Somme Battle of the Somme July-November 1916 By Ger Browne July-November 1916 1 Claremen who fought at The Somme in 1916 The Battle of the Somme started on July 1st 1916 and lasted until November 18th 1916. For many people, it was the battle that symbolised the horrors of warfare in World War One. The Battle Of the Somme was a series of 13 battles in 3 phases that raged from July to November. Claremen fought in all 13 Battles. Claremen fought in 28 of the 51 British and Commonwealth Divisions, and one of the French Divisions that fought at the Somme. The Irish Regiments that Claremen fought in at the Somme were The Royal Munster Fusiliers, The Royal Irish Regiment, The Royal Irish Fusiliers, The Royal Irish Rifles, The Connaught Rangers, The Leinster Regiment, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers and The Irish Guards. Claremen also fought at the Somme with the Australian Infantry, The New Zealand Infantry, The South African Infantry, The Grenadier Guards, The King’s (Liverpool Regiment), The Machine Gun Corps, The Royal Artillery, The Royal Army Medical Corps, The Royal Engineers, The Lancashire Fusiliers, The Bedfordshire Regiment, The London Regiment, The Manchester Regiment, The Cameronians, The Norfolk Regiment, The Gloucestershire Regiment, The Westminister Rifles Officer Training Corps, The South Lancashire Regiment, The Duke of Wellington's (West Riding Regiment). At least 77 Claremen were killed in action or died from wounds at the Somme in 1916. Hundred’s of Claremen fought in the Battle. -

January 2020 Tea Time Types Of

January 2020 Tea Time We're back this month for more tips on healthy living! January is National Hot Tea Month, so we will discuss the health benefits associated with tea. There are many different types of tea and each has its own benefits. Tea versus coffee is often a hot topic, but there are pros and cons to both drinks. Tea can also be prepared with ice in the warmer months for a refreshing effect. Types of Tea Studies have found that some teas may help with cancer, heart disease, and diabetes; encourage weight loss; lower cholesterol; and bring about mental alertness. Tea also appears to have antimicrobial qualities. Green Tea Made with steamed tea leaves, it has a high concentration of EGCG, a helpful plant compound that has been widely studied. Green tea’s antioxidants may interfere with the growth of many cancers; prevent clogging of the arteries, burn fat, counteract oxidative stress on the brain, reduce risk of neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, reduce risk of stroke, and improve cholesterol levels. Black Tea Made with fermented tea leaves, black tea has the highest caffeine content and forms the basis for flavored teas like chai, along with some instant teas. Studies have shown that black tea may protect lungs from damage caused by exposure to cigarette smoke. It also may reduce the risk of stroke. White Tea It is uncured and unfermented. One study showed that white tea has the most potent anticancer properties compared to more processed teas. Oolong Tea In an animal study, those given antioxidants from oolong tea were found to have lower bad cholesterol levels.