Ghost Brian Phillip Whalen Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hay Any Work for Cooper 1 ______

MARPRELATE TRACTS: HAY ANY WORK FOR COOPER 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ Hay Any Work For Cooper.1 Or a brief pistle directed by way of an hublication2 to the reverend bishops, counselling them if they will needs be barrelled up3 for fear of smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state, that they would use the advice of reverend Martin for the providing of their cooper. Because the reverend T.C.4 (by which mystical5 letters is understood either the bouncing parson of East Meon,6 or Tom Cook's chaplain)7 hath showed himself in his late Admonition To The People Of England to be an unskilful and beceitful8 tub-trimmer.9 Wherein worthy Martin quits himself like a man, I warrant you, in the modest defence of his self and his learned pistles, and makes the Cooper's hoops10 to fly off and the bishops' tubs11 to leak out of all cry.12 Penned and compiled by Martin the metropolitan. Printed in Europe13 not far from some of the bouncing priests. 1 Cooper: A craftsman who makes and repairs wooden vessels formed of staves and hoops, as casks, buckets, tubs. (OED, p.421) The London street cry ‘Hay any work for cooper’ provided Martin with a pun on Thomas Cooper's surname, which Martin expands on in the next two paragraphs with references to hubs’, ‘barrelling up’, ‘tub-trimmer’, ‘hoops’, ‘leaking tubs’, etc. 2 Hub: The central solid part of a wheel; the nave. (OED, p.993) 3 A commodity commonly ‘barrelled-up’ in Elizabethan England was herring, which probably explains Martin's reference to ‘smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state’. -

Sault Tribe Receives $2.5M Federal HHS Grant Tribe Gets $1.63 Million

In this issue Recovery Walk, Pages 14-15 Tapawingo Farms, Page 10 Squires 50th Reunion, Page 17 Ashmun Creek, Page 23 Bnakwe Giizis • Falling Leaves Moon October 7 • Vol. 32 No. 10 Win AwenenOfficial newspaper of the SaultNisitotung Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians Sault Tribe receives $2.5M federal HHS grant The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of diseases such as diabetes, heart tobacco-free living, active living blood pressure and high choles- visit www.healthysaulttribe.net. Chippewa Indians is one of 61 disease, stroke and cancer. This and healthy eating and evidence- terol. Those wanting to learn more communities selected to receive funding is available under the based quality clinical and other To learn more about Sault Ste. about Community Transformation funding in order to address tobac- Affordable Care Act to improve preventive services, specifically Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians’ Grants, visit www.cdc.gov/com- co free living, active and healthy health in states and communities prevention and control of high prevention and wellness projects, munitytransformation. living, and increased use of high and control health care spending. impact quality clinical preventa- Over 20 percent of grant funds tive services across the tribe’s will be directed to rural and fron- seven-county service area. The tier areas. The grants are expected U.S. Department of Health and to run for five years, with projects Human Services announced the expanding their scope and reach grants Sept. 27. over time as resources permit. The tribe’s Community Health According to Hillman, the Sault Department will receive $2.5 mil- Tribe’s grant project will include lion or $500,000 annually for five working with partner communities years. -

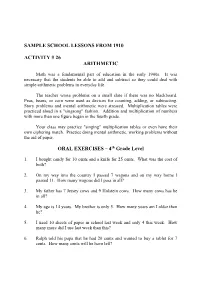

Sample School Lessons from 1910 Activity # 26 Arithmetic

SAMPLE SCHOOL LESSONS FROM 1910 ACTIVITY # 26 ARITHMETIC Math was a fundamental part of education in the early 1900s. It was necessary that the students be able to add and subtract so they could deal with simple arithmetic problems in everyday life. The teacher wrote problems on a small slate if there was no blackboard. Peas, beans, or corn were used as devices for counting, adding, or subtracting. Story problems and mental arithmetic were stressed. Multiplication tables were practiced aloud in a "singsong" fashion. Addition and multiplication of numbers with more than one figure began in the fourth grade. Your class may practice "singing" multiplication tables or even have their own ciphering match. Practice doing mental arithmetic, working problems without the aid of paper. ORAL EXERCISES – 4th Grade Level 1. I bought candy for 10 cents and a knife for 25 cents. What was the cost of both? 2. On my way into the country I passed 7 wagons and on my way home I passed 11. How many wagons did I pass in all? 3. My father has 7 Jersey cows and 9 Holstein cows. How many cows has he in all? 4. My age is 14 years. My brother is only 5. How many years am I older then he? 5. I used 10 sheets of paper in school last week and only 4 this week. How many more did I use last week than this? 6. Ralph told his papa that he had 20 cents and wanted to buy a tablet for 7 cents. How many cents will he have left? 7. -

Coaster Brook Trout: the History & Future Artist Profile: Ted Hansen Swinging for Steelhead

Trout Unlimited MINNESOTAThe Official Publication of Minnesota Trout Unlimited - February 2019 March 15th-17th, 2019 l Tickets on Sale Now! without written permission of Minnesota Trout Unlimited. Trout Minnesota of permission written without Copyright 2019 Minnesota Trout Unlimited - No portion of this publication may be reproduced reproduced be may publication this of portion No - Unlimited Trout Minnesota 2019 Copyright Shore Fishing Lake Superior Coaster Brook Trout: The History & Future Artist Profile: Ted Hansen Swinging for Steelhead MNTU Year in Review ROCHESTER, MN ROCHESTER, PERMIT NO. 281 NO. PERMIT Chanhassen, MN 55317-0845 MN Chanhassen, PAID P.O. Box 845 Box P.O. Tying the CDC & Elk U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Minnesota Trout Unlimited Trout Minnesota Non-Profit Org. Non-Profit Trout Unlimited Minnesota Council Update MINNESOTA The Voice of MNTU Meet You at the Expo! By Steve Carlton, Minnesota Council Chair On The Cover appy 2019! May the new year program. The program had a very im- bring more fish and more fishing pressive first half of the school year. Fish A coaster brook trout from Lake Su- Hopportunities…in more fishy tanks in schools around the state are now perior is ready to be released. Learn places! Since our last newsletter, I have filled with young trout growing toward about coaster brook trout, their chal- not had the time to get out, so all I can do release in the spring. Our education lenges, and current work on their be- is look forward to my next opportunity. program can always use your help and half on page 4. -

Jrnuhl00fren.Pdf

OAK ST. HDSF UNDERGRADUATE LIBRARY, The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library L161 O-1096 JORN UHL JORN UHL BY GUSTAV FRENSSEN TRANSLATED BY F. S. D ELMER ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE AND COMPANY, LTD. 1905 Edinburgh : T. and A. CONSTABLE, Printers to His Majesty - I F 8 g 7 HOST s 2 A PREFATORY NOTE GUSTAV FRENSSEN, the author of Jorn Uhl, was born in the J =3 remote village of Barlt, in Holstein, North Germany, on October 19, 1863. His father is a carpenter in this village, and, according to the church register, the Frenssen family has lived there as long as ever such records have been kept in the parish. In spite of his father's humble circumstances, Gustav Frenssen managed to attend the Latin School at the neighbouring town of Husum, and in due time became a student of theology. He heard courses of lectures at various Universities, passed the necessary examinations, and finally, -after long years of waiting, was appointed to the care of souls in the little Lutheran pastorate of Hemme in Holstein. Here within sound of the North Sea, and under the mossy thatch of the old-fashioned manse, he wrote his first two books, Die Sandgrafin and Die drei Getreuen. These two novels remained almost unknown until after the publication of Jorn Uhl in 1902. This book took Germany by storm. -

View / Open Biebelle Patricia Z Mfa2010sp.Pdf

IF I AM A STRANGER by PATRICIA Z. BIEBELLE A THESIS Presented to the Creative Writing Program and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofFine Arts June 2010 11 "If! Am a Stranger," a thesis prepared by Patricia Z. Biebelle in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofFine Arts degree in the Creative Writing Program. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: 20 (0 Date Accepted by: ~~ Dean ofthe Graduate School 111 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Patricia Z. Biebelle PLACE OF BIRTH: Carlsbad, New Mexico DATE OF BIRTH: November 27,1979 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University ofOregon, Eugene, Oregon New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, New Mexico DEGREES AWARDED: Master ofFine Arts, Creative Writing, June 2010, University ofOregon Bachelor ofArts, English, May 2008, New Mexico State University PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: Graduate Teaching Fellow, University ofOregon English Department, 2009-2010 Graduate Teaching Fellow, University ofOregon Creative Writing Program, 2008-2009 GRANTS, AWARDS AND HONORS: English Department Graduate Teaching Fellowship, University ofOregon, 2009 2010 Creative Writing Graduate Teaching Fellowship, University of Oregon, 2008 2009 Penny Wilkes Scholarship in Writing and the Environment, "Obligation," University ofOregon, 2009 IV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express sincere appreciation to Associate Professor Laurie Lynn Drummond for her invaluable help with this manuscript. In addition, special thanks are due to Timothy Ahearne, my husband, whose steadfast support made this project possible, and whose love and consideration are the cornerstones ofmy success. I also thank my family for their support, my M.F.A. colleagues for their patience and attention, and the fiction faculty ofthe University ofOregon Creative Writing Program for the knowledge they have shared. -

Inside Facts of Stage and Screen (February 7, 1931)

STAGE PRICE lO CENTS RADIO SCREEN Only Theatrical MUSIC Newspaper on the Pacific Coast j EDITED BY JACK JOSEPHS ESTABLISHED 1924 Entered Vol. XIII as Second Class Matter, April 29, 1927, at Post- office, Los. Angeles, Calif., Published Every Saturday at 809 Warner Bros Down- under Act ’ Saturday, of March 3, 1879 February 7, 1931 town Building. 401 West Seventh St., Los Angeles, Calif. No. 5 PLAN ‘JITNEY THEATRE’ CHAIN FOR PAC. COAST +- Press and MX Group Show Biz To Finance In Clash 10c Houses ' A war which has been , brewing leaf theatre ween local interests and A chain of miniature theatres, of the local press was all set to break two hundred seating capacity and oqt in dead earnest this week. to operate on a 10 cents admission Illustrated The Los Angeles schedule, is planned by a Nip-tY. -"k Daily, News, a morning- tabloid, orgr’fization which ha? fired broadside • • a into show busi- sodufcs on the toa-on. ove ness under a five-column line on prospects for nikiatiiifc Jha.., of page 2 their Thursday editions, here. panning the gala premiere policy to a fare-ye-well. While the News The plan is to spot the houses in shot was particularly at the pre- class picture neighborhoods, play- miere of RKO’s “Cimarron” at the ing opposition to the 65 centers and Orpheum Theatre, it was a crack relying for their draw on the smaii at the whole premiere practice. admission fee. ' Info from inside the battle lines, The program will be a feature, a coupled up with the fact that the comedy and a newsreel. -

These Strange Criminals: an Anthology Of

‘THESE STRANGE CRIMINALS’: AN ANTHOLOGY OF PRISON MEMOIRS BY CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS FROM THE GREAT WAR TO THE COLD WAR In many modern wars, there have been those who have chosen not to fight. Be it for religious or moral reasons, some men and women have found no justification for breaking their conscientious objection to vio- lence. In many cases, this objection has lead to severe punishment at the hands of their own governments, usually lengthy prison terms. Peter Brock brings the voices of imprisoned conscientious objectors to the fore in ‘These Strange Criminals.’ This important and thought-provoking anthology consists of thirty prison memoirs by conscientious objectors to military service, drawn from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and centring on their jail experiences during the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War. Voices from history – like those of Stephen Hobhouse, Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, Ian Hamilton, Alfred Hassler, and Donald Wetzel – come alive, detailing the impact of prison life and offering unique perspectives on wartime government policies of conscription and imprisonment. Sometimes intensely mov- ing, and often inspiring, these memoirs show that in some cases, indi- vidual conscientious objectors – many well-educated and politically aware – sought to reform the penal system from within either by publicizing its dysfunction or through further resistance to authority. The collection is an essential contribution to our understanding of criminology and the history of pacifism, and represents a valuable addition to prison literature. peter brock is a professor emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Toronto. -

Get a PDF Copy of Morgan's Voice

Morgan's Voice POEMS& STORIES Morgan Segal Copyright © 1997 by RobertSegal All rights reserved. Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data Segal,Morgan Morgan's Voice Poems8c Stories ISBN 0-9662027-0-8 First Edition 1997 Designedby RileySmith Printed in the United Statesof America by PacificRim Printers/Mailers 11924 W. Washington Blvd. LosAngeles, CA 90066 Printed on acid-free, recycled paper. The gift of sharing so intimately in Morgan's life, through her prose and poetry, is one all will commit to their hearts. Here are remembrances, emotionally inspired, of personal journeys through a landscape of experience that has been both tranquil and turbulent. Her poems are "pearls dancing," shimmering like her own life in an all too brief sunlight; her stories portraits, at times fragile, at times triumphant in their will to witness lasting humaness. She is tmly a talent and a presence too soon lost. -James Ragan, Poet Director, Professional Writing Program University of Southern California Morgan possessed a rare and beautiful soul. Those wide brown eyes of hers shone forth with a child's curiosity and innocence. But her heart was the heart of woman who was haunted by unfathomable darkness. Morgan's words are infused with depth, wisdom, honesty, courage and insight. Her descriptions reveal the intense thirst she had for even the most mundane aspects of life -- a fingernail, the scale of a fish, a grandfather's breath, a strand of hair. The attention she pays to details can help us to return to our lives with a renewed revereance for all the subtle miracles that surround us each moment. -

MY BERKSHIRE B Y

MY BERKSHIRE b y Eleanor F . Grose OLA-^cr^- (\"1S MY BERKSHIRE Childhood Recollections written for my children and grandchildren by Eleanor F. Grose POSTSCIPT AND PREFACE Instead of a preface to my story, I am writing a postscript to put at the beginning! In that way I fulfill a feeling that I have, that now that I have finished looking back on my life, I am begin' ning again with you! I want to tell you all what a good and satisfying time I have had writing this long letter to you about my childhood. If it hadn’t been for you, I wouldn’t have had the fun of thinking about and remembering and trying to make clear the personalities of my father and mother and making them integrated persons in some kind of perspective for myself as well as for you—and I have en joyed it all very much. I know that I will have had the most fun out of it, but I don’t begrudge you the little you will get! It has given me a very warm and happy feeling to hear from old friends and relatives who love Berkshire, and to add their pleasant memo ries to mine. But the really deep pleasure I have had is in linking my long- ago childhood, in a kind of a mystic way, in my mind, with you and your future. I feel as if I were going on with you. In spite of looking back so happily to old days, I find, as I think about it, that ever since I met Baba and then came to know, as grown-ups, my three dear splendid children and their children, I have been looking into the future just as happily, if not more so, as, this win ter, I have been looking into the past. -

Sperry Horse Sale

WELCOME The Sperry Ranch welcomes you to our 13th Annual Performance and Production Sale. We have chosen to move the sale to the ranch at Trotters, ND. We just felt it was time to bring it home. We hope you are as excited about it as we are. We are excited to show you our ranch and operation. We have something for everyone at this sale, so come prepared to fi nd what you’re looking for. We are selling what we think is an outstanding set of ranch-bred weanlings and performance ranch horses. All these horses are bred to perform whether you need something to rodeo on, to use on a daily basis on the ranch or enjoy for trail riding, ranch horse competitions, team pen- ning or pleasure riding. Our weanlings are out of the stallions featured on pages 2 – 4. They come from lines including Docs Oak, Play Gun, Young Gun and Paddys Irish Whiskey. The other foals offered in the sale come from Robert’s Aunt Ginger and Uncle Gary DeCock. They are out of PBR Seco Bart. We are also offering foals from Enoch and Dixie Schaffer, Robert’s cousin, that are out of Romeo White Feathers. Our goal in selecting our stallions and mares is to produce horses that can perform in The Sperry Family (L to R): Marcia, Kolby, Kanon, any situation to be the “using kind.” Robert and Tamra Sperry The foals have been handled, halter broke and dewormed. Our performance horses have all been used on our ranch or on our neighbors’ ranches to drag calves to the fi re during branding, gather mares for breeding or gather calves in the fall for shipping. -

Ellis & Associates, Inc

INTERNATIONAL LIFEGUARD Training Program Manual 5th Edition Meets ECC, MAHC, and OSHA Guidelines Ellis & Associates, Inc. 5979 Vineland Rd. Suite 105 Orlando, FL 32819 www.jellis.com 800-742-8720 Copyright © 2020 by Ellis & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated in writing by Ellis & Associates, the recipient of this manual is granted the limited right to download, print, photocopy, and use the electronic materials to fulfill Ellis & Associates lifeguard courses, subject to the following restrictions: • The recipient is prohibited from downloading the materials for use on their own website. • The recipient cannot sell electronic versions of the materials. • The recipient cannot revise, alter, adapt, or modify the materials. • The recipient cannot create derivative works incorporating, in part or in whole, any content of the materials. For permission requests, write to Ellis & Associates, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address above. Disclaimer: The procedures and protocols presented in this manual and the course are based on the most current recommendations of responsible medical sources, including the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) Consensus Guidelines for CPR, Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) and First Aid, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards 1910.151, and the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC). The materials have been reviewed by internal and external field experts and verified to be consistent with the most current guidelines and standards. Ellis & Associates, however, make no guarantee as to, and assume no responsibility for, the correctness, sufficiency, or completeness of such recommendations or information. Additional procedures may be required under particular circumstances. Ellis & Associates disclaims all liability for damages of any kind arising from the use of, reference to, reliance on, or performance based on such information.