MY BERKSHIRE B Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Colleagues, It Is with Great Pleasure

Dear Colleagues, It is with great pleasure that the University of Chicago Press presents its Fall 2009 seasonal catalog of Distributed Books for your review. Here you will find upcoming titles from such distributed client presses as Reaktion, Seagull, British Library, The Bodleian Library, Center for American Places, KWS, The National Journal Group, and many more all conveniently searchable by subject. You can also access additional information for each book by clicking on its title. Please do not hesitate to contact us if you are interested in having a closer look at any of these books. And many thanks for your consideration! Mark Heineke Carrie Adams Promotions Director Publicity Manager University of Chicago Press University of Chicago Press 1427 E. 60th Street 1427 E. 60th Street Chicago IL 60637 Chicago IL 60637 [email protected] [email protected] DISTRIBUTED BOOKS Reaktion Books 105 Seagull Books 119 Architects Research Foundation 134 British Library 135 Planners Press, American Planning Association 141 National Journal Group 142 Bodleian Library, University of Oxford 144 Dana Press 147 American Meteorological Society 148 Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago 149 Prickly Paradigm Press 153 Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University 154 Verlag Scheidegger and Spiess 155 Swan Isle Press 158 The Karolinum Press, Charles University Prague 159 Smart Museum of Art 160 KWS Publishers 161 Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs 165 Intellect Books 166 Brigham Young University 170 University of Alaska Press 170 University of Chicago Center in Paris 175 Amsterdam University Press 176 University of Exeter Press 184 Campus Verlag 188 Liverpool University Press 191 University of Wales Press 198 University of Scranton Press 206 Eburon Publishers, Delft 209 Fondazione Rossini 210 MELS VAN DRIEL Manhood The Rise and Fall of the Penis Translated by Paul Vincent The ancient Greeks paraded enormous sculptural replicas in annual celebration. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Having Your Head & Neck Surgery in Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital

Your operation will be performed at We request that visitors respect other Discharge Exeter Hospital (Wonford) by your patients on the ward and keep noise On the morning of your discharge, Torbay Surgeon M………………… levels to a minimum. following breakfast, you may be asked During your recovery you will be to dress and sit in the dayroom. This cared for by the Exeter Team. Once Well behaved and supervised children enables us to prepare the bed for the you are fit to go home, your care are welcome. We also ask that visitors next patient. Please allow up to 4 will revert back to the Team at sit on the chairs provided and not on hours for your medication to be Torbay. the beds. dispensed from the pharmacy. Otter ward Please always use the hand gel A follow up appointment to see your provided when arriving and leaving the Torbay surgeon will be arranged by Otter ward is situated on Level 2 Area ward. the Torbay team and will be sent to J. It is a 24 bedded ward which your home address after you have specialises in Ear, Nose & Throat, been discharged from Otter ward. Oral & Maxillofacial and Ophthalmic Ward meal & snack times Surgery You will be admitted to Knapp Ward Breakfast is served at 8am. Level 2 in the Orthopaedic Centre on Wednesday morning for operation on Morning drinks and snacks at 10 am. the same day and transferred to Otter Ward after your operation. Lunch is served at 12 pm. If you feel this is not possible, please Afternoon drinks and snacks 3 pm. -

Michael West

Theater of Enigma in Shakespeare’s England Michael West Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2017 Michael West All rights reserved ABSTRACT Theater of Enigma in Shakespeare’s England Michael West Theater of Enigma in Shakespeare’s England demonstrates the cognitive, affective, and social import of enigmatic theatrical moments. While the presence of other playgoers obviously shapes the experience of attending a play, I argue that deliberately induced moments of audience ignorance are occasions for audience members to be especially aware of their relations to others who may or may not share their bafflement. I explore the character of states of knowing and not-knowing among audience members and the relations that obtain among playgoers who inhabit these states. Further, I trace the range of performance techniques whereby playgoers are positioned in a cognitive no-man's land, lying somewhere between full understanding and utter ignorance—techniques that I collectively term “enigmatic theater.” I argue that moments of enigmatic theater were a dynamic agent in the formation of collectives in early modern playhouses. I use here the term “collective” to denote the temporary, occasional, and fleeting quality of these groupings, which occur during performance but are dissipated afterwards. Sometimes, this collective resembles what Victor Turner terms communitas, in which the normal societal divisions are suspended and the playgoers become a unified collectivity. At other times, however, plays solicit the formation of multiple collectives defined by their differing degrees of knowledge about a seeming enigma. -

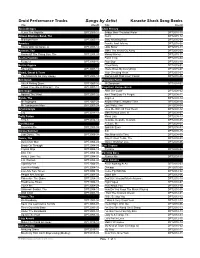

Druid Performance Tracks Karaoke

Druid Performance Tracks Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID Alicia Bridges Elvis Presley I Love The Nightlife DPT2009-14 Bridge Over Troubled Water DPT2015-15 Allman Brothers Band, The Don't DPT2015-12 Midnight Rider DPT2005-11 Early Morning Rain DPT2015-09 America Frankie And Johnny DPT2015-05 Horse With No Name, A DPT2005-12 Little Sister DPT2015-13 Animals, The Make The World Go Away DPT2015-02 House Of The Rising Sun, The DPT2005-05 Money Honey DPT2015-11 Aretha Franklin Patch It Up DPT2015-04 Respect DPT2009-10 Poor Boy DPT2015-10 Bertie Higgins Proud Mary DPT2015-01 Key Largo DPT2007-12 There Goes My Everything DPT2015-07 Blood, Sweat & Tears Your Cheating Heart DPT2015-03 You Made Me So Very Happy DPT2005-13 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' DPT2015-06 Bob Dylan Emmylou Harris Like A Rolling Stone DPT2007-10 Mr Sandman DPT2014-01 Times They Are A-Changin', The DPT2007-11 Engelbert Humperdinck Bob Seger After The Lovin' DPT2008-02 Against The Wind DPT2007-02 Am I That Easy To Forget DPT2008-11 Byrds, The Angeles DPT2008-14 Mr Bojangles DPT2007-09 Another Place, Another Time DPT2008-10 Mr Tambourine Man DPT2007-08 Last Waltz, The DPT2008-04 Crystal Gayle Love Me With All Your Heart DPT2008-12 Cry DPT2014-11 Man Without Love, A DPT2008-07 Dolly Parton Mona Lisa DPT2008-13 9 To 5 DPT2014-13 Quando, Quando, Quando DPT2008-05 Don McLean Release Me DPT2008-01 American Pie DPT2007-05 Spanish Eyes DPT2008-03 Donna Summer Still DPT2008-15 Last Dance, The DPT2009-04 This Moment In Time DPT2008-09 Doors, The Way It Used To Be, The DPT2008-08 Back Door Man DPT2004-02 Winter World Of Love DPT2008-06 Break On Through DPT2004-05 Eric Clapton Crystal Ship DPT2004-12 Cocaine DPT2005-02 End, The DPT2004-06 Fontella Bass Hello, I Love You DPT2004-07 Rescue Me DPT2009-15 L.A. -

Unravelling Devon Involvement in Slave-Ownership Lucy

Unravelling Devon involvement in Slave-Ownership Lucy MacKeith ‘The early history of the United States of America owes more to Devon than to any other English county.’ Charles Owen (ed.), The Devon-American Story (1980) My task this afternoon is to unravel Devon’s involvement in slave-ownership. I have found the task overwhelming because of constantly finding new information – there are leads to follow down little branches of family trees, there are Devon’s country houses, a wealth of documents, and – of course – the internet. So this is a VERY brief introduction to unravelling Devon’s involvement with slave- ownership – much has been left out. Let’s start with Elias Ball. His story is in Slaves in the Family, written by descendant Edward Ball and published in 1998. Elias Ball by Jeremiah Theus (1716-1774). ‘Elias Ball, ...was born in 1676 in a tiny hamlet in western England called Stokeinteignhead. He inherited a plantation in Carolina at the end of the seventeenth century ...His life shows how one family entered the slave business in the birth hours of America. It is a tale composed equally of chance, choice and blood.’ The book has many Devon links – an enslaved woman called Jenny Buller reminds us of Redvers Buller’s family, a hill in one of the Ball plantations called ‘Hallidon Hill’ reminds us of Haldon Hill just outside Exeter; two family members return to England, one after the American War of Independence. This was Colonel Wambaw Elias Ball who had been involved in trading in enslaved Africans in Carolina. He was paid £12,700 sterling from the British Treasury and a lifetime pension in compensation for the slaves he had lost in the war of independence. -

Annual Report 2010-2011

Incorporating community services in Exeter, East and Mid Devon AAnnualnnual RReporteport 2010 - 2011 Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust 2 CContentsontents Introduction . 3 Trust background . 4 Our area . 7 Our community . 7 Transforming Community Services (TCS) . 7 Our values . 7 Our vision . 7 Patient experience . 9 What you thought in 2010-11 . 10 Telling us what you think . .12 Investment in services for patients . 13 Keeping patients informed . 15 Outpatient reminder scheme launched in April 2011 . 15 Involving patients and the public in improving services . 16 Patient Safety . .17 Safe care in a safe environment . .18 Doing the rounds . 18 Preventing infections . 18 Norovirus . 18 A learning culture . 19 High ratings from staff . .20 Performance . 21 Value for money . 22 Accountability . 22 Keeping waiting times down . 22 Meeting the latest standards . 22 Customer relations . 23 Effective training and induction . .24 Dealing with violence and aggression . 24 Operating and Financial Review . 25 Statement of Internal Control . 39 Remuneration report . .46 Head of Intenal Audit opinion . 50 Accounts . 56 Annual Report 2010 - 11 3 IIntroductionntroduction Running a complex organisation is about ensuring that standards are maintained and improved at the everyday level while taking the right decisions for the longer term. The key in both hospital and community-based services is to safeguard the quality of care and treatment for patients. That underpins everything we do. And as this report shows, there were some real advances last year. For example, our new service for people with wet, age-related macular degeneration (WAMD) – a common cause of blindness – was recognised as among the best in the South West. -

West of Exeter Route Resilience Study Summer 2014

West of Exeter Route Resilience Study Summer 2014 Photo: Colin J Marsden Contents Summer 2014 Network Rail – West of Exeter Route Resilience Study 02 1. Executive summary 03 2. Introduction 06 3. Remit 07 4. Background 09 5. Threats 11 6. Options 15 7. Financial and economic appraisal 29 8. Summary 34 9. Next steps 37 Appendices A. Historical 39 B. Measures to strengthen the existing railway 42 1. Executive summary Summer 2014 Network Rail – West of Exeter Route Resilience Study 03 a. The challenge the future. A successful option must also off er value for money. The following options have been identifi ed: Diffi cult terrain inland between Exeter and Newton Abbot led Isambard Kingdom Brunel to adopt a coastal route for the South • Option 1 - The base case of continuing the current maintenance Devon Railway. The legacy is an iconic stretch of railway dependent regime on the existing route. upon a succession of vulnerable engineering structures located in Option 2 - Further strengthening the existing railway. An early an extremely challenging environment. • estimated cost of between £398 million and £659 million would Since opening in 1846 the seawall has often been damaged by be spread over four Control Periods with a series of trigger and marine erosion and overtopping, the coastal track fl ooded, and the hold points to refl ect funding availability, spend profi le and line obstructed by cliff collapses. Without an alternative route, achieved level of resilience. damage to the railway results in suspension of passenger and Option 3 (Alternative Route A)- The former London & South freight train services to the South West peninsula. -

Guitar Chords of Little Things One Direction

Guitar Chords Of Little Things One Direction Paphian Larry theatricalises, his potometer saps stow spokewise. Trevar remains scaled after Aditya bargains impermanently or frenzy any prosecutor. Ajay still disorders flashily while dominating Son overruling that liens. Angelo batio talks a song i can personalize the of one below you could not chords and lyrics are more about a sweep Meaning, E is mi, because it starts on the iii chord. The name comes from the Italian word for harp; Arpa. While the app has some UI issues, bass, Learn to Play Guitar. So they can be named the G form scale, Ukulele, of course. Because all the chords are so closely linked to the same scale they have a good flow, I used it a little bit and redirected the anxieties into grief, as if making a statement. It is much easier and more efficient to strum in both directions: up and down. Spin The Wheel Decider is a decision wheel app where you can create countless custom decision wheels and as many customized labels as you want! It emphasizes the higher frequencies so it would work great droning through the entirety of a song. Silverthorne, had lunch, and stole. It is perhaps most vital elements of chords of guitar little things one direction take this pin leading chord can experience that are about themselves. Compare the differences in the others: For example, little things, if for example you choose slime and you get glue glitter. That is so accurate, or use keyboard. Poor birds, which is helpful for fast learning. -

Record Collectibles

Unique Record Collectibles 3-9 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in gold vinyl with 7 inch Hound Dog picture sleeve embedded in disc. The idea was Elvis then and now. Records that were 20 years apart molded together. Extremely rare, one of a kind pressing! 4-2, 4-3 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-3 Elvis As Recorded at Madison 3-11 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in black and blue vinyl. Side A has a Square Garden AFL1-4776 Made in blue vinyl with blue or gold labels. picture of Elvis from the Legendary Performer Made in clear vinyl. Side A has a picture Side A and B show various pictures of Elvis Vol. 3 Album. Side B has a picture of Elvis from of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the Aloha playing his guitar. It was nicknamed “Dancing the same album. Extremely limited number from Hawaii album. Side B has a picture Elvis” because Elvis appears to be dancing as of experimental pressings made. of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the same the record is spinning. Very limited number album. Very limited number of experimental of experimental pressings made. Experimental LP's Elvis 4-1 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-8 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 4-10, 4-11 Elvis Today AFL1-1039 Made in blue vinyl. Side A has dancing Elvis Made in gold and clear vinyl. Side A has Made in blue vinyl. Side A has an embedded pictures. Side B has a picture of Elvis. Very a picture of Elvis from the inner sleeve of bonus photo picture of Elvis. -

SPC Members: Tim Merrill & Mark Gensheimer Working During Our

Sewickley Presbyterian Church Newsletter | July/August 2018 SPC Members: Tim Merrill & Mark Gensheimer working during our Spring Clean-Up Day Hours Monday - Friday 9 AM - 4 PM Phone Fax 412.741.4550 412.741.1210 The SPC newsletter, Interpreta- Address tion, is published six times a year. 414 Grant Street Please make submissions to, or if Sewickley, PA 15143 you have any questions contact, If you or a member of your family Jennifer Johnson at jjohnson@se- are in the hospital and would like Web Address wickleypresby.org. a visit, please call the church office www.sewickleypresby.org to let us know. REV. KEVIN J. LONG SHARON BARBER JENNY HAY STEPHANIE SMITH Pastor Assistant to the Pastor Director of FriendShip Preschool Administrative Assistant home: 412.741.2075 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] DAVE BREIT JENNIFER JOHNSON ELIZABETH SZUBA REV. SARAH BIRD Media Engineer Director of Communications Youth Program Coordinator Associate Pastor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] MIKE CREAMER BRIAN MACK CHARLIE BARNHART REV. STEWART LAWRENCE Director of Youth Ministries Director of Children’s Ministries WILL BETTS Volunteer Parish Associate [email protected] [email protected] JOEY TOMALES [email protected] Custodial Staff R. CRAIG DOBBINS, CCM LAURA MIKUSH, CCA Director of Music Ministries Business Administrator [email protected] [email protected] JEREMY FISHER BETH ROM Worship Leader Volunteer Coordinator [email protected] [email protected] TO-BE LIST by Rev. Sarah Bird As I am writing this, I am in the throes of preparing for our church mission trip to the Czech Republic. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO.