View / Open Biebelle Patricia Z Mfa2010sp.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

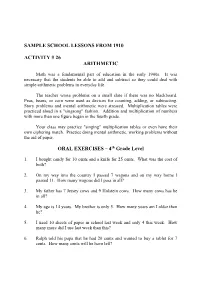

Sample School Lessons from 1910 Activity # 26 Arithmetic

SAMPLE SCHOOL LESSONS FROM 1910 ACTIVITY # 26 ARITHMETIC Math was a fundamental part of education in the early 1900s. It was necessary that the students be able to add and subtract so they could deal with simple arithmetic problems in everyday life. The teacher wrote problems on a small slate if there was no blackboard. Peas, beans, or corn were used as devices for counting, adding, or subtracting. Story problems and mental arithmetic were stressed. Multiplication tables were practiced aloud in a "singsong" fashion. Addition and multiplication of numbers with more than one figure began in the fourth grade. Your class may practice "singing" multiplication tables or even have their own ciphering match. Practice doing mental arithmetic, working problems without the aid of paper. ORAL EXERCISES – 4th Grade Level 1. I bought candy for 10 cents and a knife for 25 cents. What was the cost of both? 2. On my way into the country I passed 7 wagons and on my way home I passed 11. How many wagons did I pass in all? 3. My father has 7 Jersey cows and 9 Holstein cows. How many cows has he in all? 4. My age is 14 years. My brother is only 5. How many years am I older then he? 5. I used 10 sheets of paper in school last week and only 4 this week. How many more did I use last week than this? 6. Ralph told his papa that he had 20 cents and wanted to buy a tablet for 7 cents. How many cents will he have left? 7. -

Coaster Brook Trout: the History & Future Artist Profile: Ted Hansen Swinging for Steelhead

Trout Unlimited MINNESOTAThe Official Publication of Minnesota Trout Unlimited - February 2019 March 15th-17th, 2019 l Tickets on Sale Now! without written permission of Minnesota Trout Unlimited. Trout Minnesota of permission written without Copyright 2019 Minnesota Trout Unlimited - No portion of this publication may be reproduced reproduced be may publication this of portion No - Unlimited Trout Minnesota 2019 Copyright Shore Fishing Lake Superior Coaster Brook Trout: The History & Future Artist Profile: Ted Hansen Swinging for Steelhead MNTU Year in Review ROCHESTER, MN ROCHESTER, PERMIT NO. 281 NO. PERMIT Chanhassen, MN 55317-0845 MN Chanhassen, PAID P.O. Box 845 Box P.O. Tying the CDC & Elk U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Minnesota Trout Unlimited Trout Minnesota Non-Profit Org. Non-Profit Trout Unlimited Minnesota Council Update MINNESOTA The Voice of MNTU Meet You at the Expo! By Steve Carlton, Minnesota Council Chair On The Cover appy 2019! May the new year program. The program had a very im- bring more fish and more fishing pressive first half of the school year. Fish A coaster brook trout from Lake Su- Hopportunities…in more fishy tanks in schools around the state are now perior is ready to be released. Learn places! Since our last newsletter, I have filled with young trout growing toward about coaster brook trout, their chal- not had the time to get out, so all I can do release in the spring. Our education lenges, and current work on their be- is look forward to my next opportunity. program can always use your help and half on page 4. -

MY BERKSHIRE B Y

MY BERKSHIRE b y Eleanor F . Grose OLA-^cr^- (\"1S MY BERKSHIRE Childhood Recollections written for my children and grandchildren by Eleanor F. Grose POSTSCIPT AND PREFACE Instead of a preface to my story, I am writing a postscript to put at the beginning! In that way I fulfill a feeling that I have, that now that I have finished looking back on my life, I am begin' ning again with you! I want to tell you all what a good and satisfying time I have had writing this long letter to you about my childhood. If it hadn’t been for you, I wouldn’t have had the fun of thinking about and remembering and trying to make clear the personalities of my father and mother and making them integrated persons in some kind of perspective for myself as well as for you—and I have en joyed it all very much. I know that I will have had the most fun out of it, but I don’t begrudge you the little you will get! It has given me a very warm and happy feeling to hear from old friends and relatives who love Berkshire, and to add their pleasant memo ries to mine. But the really deep pleasure I have had is in linking my long- ago childhood, in a kind of a mystic way, in my mind, with you and your future. I feel as if I were going on with you. In spite of looking back so happily to old days, I find, as I think about it, that ever since I met Baba and then came to know, as grown-ups, my three dear splendid children and their children, I have been looking into the future just as happily, if not more so, as, this win ter, I have been looking into the past. -

Sperry Horse Sale

WELCOME The Sperry Ranch welcomes you to our 13th Annual Performance and Production Sale. We have chosen to move the sale to the ranch at Trotters, ND. We just felt it was time to bring it home. We hope you are as excited about it as we are. We are excited to show you our ranch and operation. We have something for everyone at this sale, so come prepared to fi nd what you’re looking for. We are selling what we think is an outstanding set of ranch-bred weanlings and performance ranch horses. All these horses are bred to perform whether you need something to rodeo on, to use on a daily basis on the ranch or enjoy for trail riding, ranch horse competitions, team pen- ning or pleasure riding. Our weanlings are out of the stallions featured on pages 2 – 4. They come from lines including Docs Oak, Play Gun, Young Gun and Paddys Irish Whiskey. The other foals offered in the sale come from Robert’s Aunt Ginger and Uncle Gary DeCock. They are out of PBR Seco Bart. We are also offering foals from Enoch and Dixie Schaffer, Robert’s cousin, that are out of Romeo White Feathers. Our goal in selecting our stallions and mares is to produce horses that can perform in The Sperry Family (L to R): Marcia, Kolby, Kanon, any situation to be the “using kind.” Robert and Tamra Sperry The foals have been handled, halter broke and dewormed. Our performance horses have all been used on our ranch or on our neighbors’ ranches to drag calves to the fi re during branding, gather mares for breeding or gather calves in the fall for shipping. -

THE TWELFTH MEETING Depend Totally on God for Our Needs

The TWELFTH Come and hear, MEETING all ye that fear God, and 1 will declare what pje hath done for Sandy Miller my soul. Ray Pichette Psalm 66:16 Charles Ferguson Max Torkelsen II Ernest M. Wolfe Floyd L. Pichler Denise Dick Herr Tom Ish R. Dean Davis George Crumley OVER AND OVER AGAIN! GOD’S WAY, NOT MINE By Sandy Miller LY ™HUSBAND is a general contractor who for many years was successful inM his business. In the 1970s interest rates skyrocketed, and construc tion came to a virtual standstill. About the same time we had the opportunity to purchase a small health food distributorship, Harvest Day Wholesalers. We decided to make the transition from building to distributing health food. Building has always been my husband’s first love, and he never put his whole heart into the health food venture. When interest rates started to fall, he started building again. As his construction opportunities increased, the responsibility of running Harvest Day fell upon my shoulders. Before long I was working 16 hours a day, six days a week, taking time off only for Sabbath. My spiritual life began to suffer. I prayed, “Lord, I need You, I need to spend time with You, but I don’t know how to get off this roller coaster that I’m on.” I had litde time for family and almost no time for the Lord. God heard my cry for help, and He answered my prayer, but not in any way I expected. One day I received a letter from a man in the health food business who was interested in buying Harvest Day. -

YOU TREAT ME LIKE a FISH and OTHER PROBLEMS a Written

YOU TREAT ME LIKE A FISH AND OTHER PROBLEMS A written creative work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Master of Fine Arts In Creative Writing: Fiction by Evelyne Aikman San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Evelyne Aikman 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read You Treat Me Like a Fish and Other Problems by Evelyne Aikman, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a written creative work submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing: Fiction at San Francisco State University. Andrew Joron Assistant Professor of Creative Writing May-lee Chai Assistant Professor of Creative Writing YOU TREAT ME LIKE A FISH AND OTHER PROBLEMS Evelyne Aikman San Francisco, California 2018 A woman who has recently left a failed relationship returns home to her parents' farm to find her family in upheaval. As she attempts to wrestle with her own emotional strife and get her family in order she reflects on her life in a series of connected vignettes. Each of these humorous installments are told from this narrator's point of view. I certify that the Annotation is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. f Chair, Written Creative Work Committee Date TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ...................................................................................vi Sick Bag ............................................................................................... -

Market Responds to Negative Pressures

The National Livestock Weekly March 10, 2008 • Vol. 87, No. 22 “The Industry’s Largest Weekly Circulation” Web site: www.wlj.net • E-mail: [email protected] • [email protected] • [email protected] A Crow Publication JBS/Swift goes on a buying spree —In one day, JBS/ mon stock. JBS will also acquire company with multiple locations National Beef to the North Amer- all of National’s outstanding to deliver the high quality cattle ican operations of his company Swift leapfrogs Cargill debt and liabilities upon the clos- they produce for our value-added was a key strategic decision. and Tyson to become ing of the transaction. programs. This opportunity will “We are looking forward to work- the largest packer in The purchase of National Beef establish a solid platform for fu- ing with (National’s) management the U.S. and the Packing added five slaughter ture company growth,” said Steve and employees to expand our busi- DELISTING BRINGS SUITSUIT— A coali- plants to JBS/Swift’s empire, in- Hunt, CEO of USPB, in making ness in the United States and in- tion of 11 environmental organiza- world. cluding two in Kansas, and one the announcement. ternationally. National Beef is an tions has delivered a notice to the each in California, Georgia and Wesley Batista, CEO of JBS industry leader in value added U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service inform- In a surprise announcement last ing the agency that they will be suing week, JBS Swift announced it had Pennsylvania. The company pro- USA, Inc., said the addition of See JBS/Swift on page 22 to keep the northern population of completed a buying spree, snap- cesses about 3.9 million head a the gray wolf on the endangered ping up two competitors in the year, or approximately 12,500 species list. -

Honest Markets and a Fair Price

What About Holding Wheat for a Dollar? Page 6 MRIL fd BREEZE 5�aCopy Volume 70 August 6, 1932 Number 16 Honest Markets and a Fair Price courts will now decide whether farmers may Trade's "free do business on the Chicago Board of market." another and open competitive It is chap ter in the farmer's long fight for honest markets and a fair price. UHE If, under the Grain Futures Act, the Chicago Board of Trade does not restore the Farmers' Grain Corpora be tion to full trading privileges by August 8, next, it will order of the suspended as a contract market for 60 days by Secretary of Agriculture, with the concurrence of the Secretary of Commerce and the Attorney General of the United States. The Board of Trade has appealed to the U. S. Circuit Court be to set aside or modify this order. The case may finally taken to the United States Supreme Court and a year's time Hoard of Trade will con may elapse. Meanwhile the Chicago tinue to do business. "This Wa fight for the life of co-operative marketing which is vital to the future of agriculture," comments Senator Arthur Capper, author of the Capper-Volstead Co-operative Act, also of the Grain Futures Act. "The Chicago Board of Trade is making desperate efforts to prevent farm marketing groups own also to from having any voice in their markets, prevent their own them from making any profits from handling prod ucts. It looks as if the grain exchanges are taking advantage of the depression to try to break the co-operatives, and do not in the I care if they ruin the farmers of the country process. -

A History of First United Methodist Church Brownwood, Texas 1875

A History Of First United Methodist Church Brownwood, Texas 1875-2019 A History of First United Methodist Church of Brownwood, Texas 1875 – 2019 by Frank T. Hilton October 2019 Dedication This book is dedicated to all members of Brownwood First United Methodist Church, past and present, which have helped make God’s word possible to the people of Brownwood, Texas. They have given their presents, their gifts, and their service on behalf of their faith in God and Jesus Christ to “make new disciples for Jesus Christ through helping others to know, love and serve Him.” We will never know the names of most of them, those names having been lost in the passage of time. But they served, they gave, and our community benefited from their gifts. I also dedicate this book to the many teachers of our Sunday school classes, the leaders of our youth, and our pastors and staff, who give untold hours in helping all of us to better understand our faith and how we can reach beyond the physical walls of our church to reach others in the name of Jesus Christ. As Dr. Don reminded us, “John Wesley never intended to create a denomination, he was focused on creating a movement.” This church is not a “place” but “the living body of Christ in the world today.” May we continue to reach out to others and bring them to Christ in the name of First United Methodist Church of Brownwood, Texas. Forward The history of First United Methodist Church of Brownwood, Texas began in the 1870s, however we are not sure exactly what date it started. -

The Amish Transcript

Page 1 The Amish Transcript Amish Man 1: Yeah, okay. Interviewer: Okay, let's chat. Amish Man 1: Tell the Cameraman to get lost! [Laughs] Slate: The Amish will not pose for photographs or allow interviews on camera. Interviewer: He doesn't come until tomorrow. Amish Man 1: Good. That's good. Interviewer: So tell me, I want to know first of all, about your family. Slate: Many Amish people allowed us to record our conversations with them. The voices in this film are theirs. Interviewer: Where did they come from, and how did they get here? Amish Man 1: Oh, well when they came to America, they landed in Philadelphia, then Benjamin Franklin... Slate: Summer. Intercourse, Pennsylvania Tour Guide: Welcome to the Amish farm and house, my name is Don, I'll be your tour guide today. Talk a bit about the Amish, and where they come from. All goes back to the Protestant Reformation, 1517, Martin Luther... Page 2 Slate: Rooted in the Protestant Reformation, the Amish church began in Europe and soon spread to North America. Today, Amish communities exist only in Canada and the United States. Tour Guide: We'll start over here, with the wardrobe. Up to the age of one year old, a little girl, or a little boy in the Amish community will wear something like this. Tourist 1: Why is it that the fashion seems to frozen in time, and yet they're wearing flip- flops? Tourist 2: Is there an identity as Americans, or... Tour Guide: I'm sure the Amish would see themselves that way. -

Firefly Curios and Sundry Lights Maidel H

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-4-1997 Firefly curios and sundry lights Maidel H. Barrett Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14050443 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Fiction Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Barrett, Maidel H., "Firefly curios and sundry lights" (1997). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1411. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1411 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida FIREFLY CURIOS AND SUNDRY LIGHTS A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN CREATIVE WRITING by Maidel H. Barrett 1997 To: } s: Hl A?- , ,i tt S k,, Maul z 1 ip 1.S .. F " i' 1.i 'E 1.t. We v ts,1t L ll ' _s_°f ,tivnd CC.;01?1111u11L9 ilia it It cli''f?14'4 . 0 1) i DIM .i 'Aarc -L "L b 41 pp 7 7 r.. 7i \f 1 For my father, John Herbert Barrett. And my mother, Lida Kittrell Barrett. And for Ronald James Dziubla. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the community of professors and writers at Florida International University. I especially want to thank my defense committee: Campbell McGrath for insight and humor, and for passing on practical procedures for becoming a teaching poet; John Dufresne for his example that poetry is not limited to poems; and Mary Jane Elkins for her eloquent and inspirational teaching. -

“Down on the Farm” Crafts

2020 Down on the Farm Resource National Book Camping School Inside this Issue: FUN! 2020 Setting the tone for FUN! Camp Station Location Names Gathering Activities Prayers Opening & Closing Ceremonies Skits Cheers/Applauses Jokes/Run-ons Songs Audience Participation Games & Activities “Down on the Farm” Crafts Snack Ideas National Camping School’s Annual Theme Program Each year a theme-related resource booklet is Theme Related Ideas produced and distributed through the Clipart Cub Scouting National Camp Schools. The material provided is designed to be used Upcoming Themes in the districts and councils presenting Cub Scout camping activities. Welcome! The material in this resource book is designed to serve your district or council in providing tremendous Cub Scout day camping events! Many resources were used to compile the information you will find in this booklet. THANK YOU to the leaders who sent in ideas and suggestions and THANK YOU to those who contributed to the resources used. We could not have done it without you!!! We appreciate your help and all that you do for our scouts and day camp!! DOWN ON THE FARM - What down home fun you will have with this theme! Learn about animals, the food that we eat – how it grows, what it takes to make it grow, how to take care of animals, doing chores, square dancing, how to raise and care for animals and having fun!!! Mazes out of hay, pool noodle horses, or tube and paper sack horses, hay rides, ring toss or corn hole games, whatever it is you choose to do or go with your theme, make it FUN and exciting! All materials in this book reflect the high standards of the BSA.