First Timers and Old Timers: the Texas Folklore Society Fire Burns On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vermont Beer : History of a Brewing Revolution Pdf, Epub, Ebook

VERMONT BEER : HISTORY OF A BREWING REVOLUTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kurt Staudter | 210 pages | 01 Jul 2014 | History Press Library Editions | 9781540210197 | English | none Vermont Beer : History of a Brewing Revolution PDF Book Seven Days needs your financial support! When Carri Uranga interviewed for a job at Magic Hat in , she sat across a table from Johnson and longtime general manager Steve Hood she thinks; memories made at breweries tend to be fuzzy, especially two decades later. Many of Magic Hat's offbeat offerings were home runs, though — so many, in fact, that by it was the eighth-largest craft brewery in the country. A hop shortage reportedly due to a fire in Washington state and bad storms in Germany leads to brewers to band together to solve a problem in the supply chain. Charleston: A Historic Walking Tour. Showing The event will include demos, meetings about the project, a book talk by Kurt Staudter, author of "Vermont Beer: History of a Brewing Revolution," and a 5 p. Richards, 34, with minimal brewing experience under his belt, became intrigued by ginger beer after reading about its historical connections to the spice-trade shipping days of yore. National sales figures confirm that craft customers, many of whom were weaned on 9, are moving away from regional breweries like Magic Hat and toward microbreweries — defined as breweries that produce fewer than 15, barrels per year. When the Pilgrims sailed for America, they hoped to find a place to settle where the farmland would be rich and the climate congenial. American Palate , Beer! Craft brewing is kind of like that. -

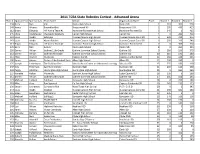

2011 TCEA State Robotics Contest

2011 TCEA State Robotics Contest - Advanced Arena Team # Sponsor First Sponsor Last Team Name School Organization Name Place Round 1 Round 2 Round 3 134 Berry Nall Viki Roma High School Roma ISD 1 510 305 500 148 James Weaver BwoodJediBot Brazoswood HS Brazosport I.S.D. 2 195 430 415 112 Bryan Edwards H-F Arena Team #1 Hamshire-Fannett High School Hamshire-Fannett ISD 3 345 0 425 145 Chris Underwood The Goofy Goobers Carroll High School Carroll ISD 4 0 280 450 142 Louis Webb Sabrijeje Nueces Canyon High School Nueces Canyon Cons ISD 5 390 220 315 143 Louis Webb Alamo Raiders Nueces Canyon High School Nueces Canyon Cons ISD 6 265 315 340 113 Bryan Edwards H-F Arena Team #2 Hamshire-Fannett High School Hamshire-Fannett ISD 7 0 300 350 135 Berry Nall Evolver Roma High School Roma ISD 8 0 265 335 150 Darren Wilson Guthrie 11th Grade Guthrie Common School District Guthrie ISD 9 180 190 375 152 Darren Wilson Guthrie 9th Grade Guthrie Common School District Guthrie ISD 10 315 145 160 147 Allan Warren Mustangs Cypress Ranch Cypress-Fairbanks ISD 11 160 160 295 100 Karen Adams Order of the Painted Rock Allen High School Allen ISD 12 260 180 0 125 Joseph Holochwost The Dubious One Victoria Area Center for Advanced Learning Victoria ISD 13 255 180 160 137 Joey Patterson Aperture Science Burleson High Burleson ISD 14 265 125 160 103 Peggy Albritton Huntington High School Huntington High School Huntington ISD 15 0 160 265 127 Nanette Kelton Mavericks Bonham Junior High School Ector County ISD 16 135 0 280 151 Darren Wilson Guthrie 10th Grade Guthrie Common School District Guthrie ISD 17 245 160 135 123 Michael Holland Bulldog 1 Banquete High School Banquete ISD 18 0 205 190 118 Mike Gray Ron Squared Cy-Fair High School Cypress-Fairbanks ISD 19 245 135 125 130 Steven Livingston Comanche Red West Texas High School P.S.P. -

2018-19 BOARD of DIRECTORS Committee Chairs and Vice Chairs

2018-19 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Committee Chairs and Vice Chairs Jason Roemer Astin Haggerty Brad Blalock President 1st Vice President 2nd Vice President Lake Dallas High School Clear Springs High School Frisco Centennial High School 830-456-4489 281-284-1368 469-633-5600 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Kriss Ethridge Jason Trook Brooke Walthall Past President Reg I, Sr Director Reg I, Jr Director Lubbock Coronado High School Lubbock High School Canyon Randall High School 806-219-1122 806-219-0806 806-677-2333 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Sunni Strickland Mitzi Bell Colby Pastusek Reg II, Sr Director Reg II, Jr Director Reg III, Sr Director Forsan High School Big Spring High School The Colony High School 432-264-3662 512-988-1435 940-232-3392 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jim Wood Kari Bensend Lindsey Gage Reg III, Jr Director Reg IV, Sr Director Reg IV, Jr Director Maypearl High School Frisco Centennial High School Anna High School 972-435-1020 469-633-5662 903-564-4220 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jennifer Knight Reagan Smith Brandace Boren Reg V, Sr Director Reg V, Jr Director Reg VI, Sr Director Clear Springs High School Cypress Creek High School Lake Travis High School 409-659-0786 281-795-6544 512-533-6104 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Anthony Branch Bernice Voigt Patti Zenner Reg VI, Jr Director Reg VII, Sr Director Reg VII, Jr Director Sealy High School -

Polka Sax Man More Salute to Steel 3 from the TPN Archives Donnie Wavra July 2006: 40Th National Polka by Gary E

Texas Polka News - March 2016 Volume 28 | Isssue 2 INSIDE Texas Polka News THIS ISSUE 2 Bohemian Princess Diary Theresa Cernoch Parker IPA fundraiser was mega success! Welcome new advertiser Janak's Country Market. Our first Spring/ Summer Fest Guide 3 Editor’s Log Gary E. McKee Polka Sax Man More Salute to Steel 3 From the TPN Archives Donnie Wavra July 2006: 40th National Polka By Gary E. McKee Festival Story on Page 4 4-5 Featured Story Polka Sax Man 6-7 Czech Folk Songs Program; Ode to the Songwriter 8-9 Steel Story Continued 10 Festival & Dance Notes 12-15 Dances, Festivals, Events, Live Music 16-17 News PoLK of A Report, Mike's Texas Polkas Update, Czech Heritage Tours Special Trip, Alex Says #Pep It Up 18-19 IPA Fundraiser Photos 20 In Memoriam 21 More Event Photos! 22-23 More Festival & Dance Notes 24 Polka Smiles Sponsored by Hruska's Spring/SummerLook for the Fest 1st Annual Guide Page 2 Texas Polka News - March 2016 polkabeat.com Polka On Store to order Bohemian Princess yours today!) Texas Polka News Staff Earline Okruhlik and Michael Diary Visoski also helped with set up, Theresa Cernoch Parker, Publisher checked people in, and did whatever Gary E. McKee, Editor/Photo Journalist was asked of them. Valina Polka was Jeff Brosch, Artist/Graphic Designer Contributors: effervescent as always helping decorate the tables and serving as a great hostess Julie Ardery Mark Hiebert Alec Seegers Louise Barcak Julie Matus Will Seegers leading people to their tables. Vernell Bill Bishop Earline Berger Okruhlik Karen Williams Foyt, the Entertainment Chairperson Lauren Haase John Roberts at Lodge 88, helped with ticket sales. -

Southeast Texas: Reviews Gregg Andrews Hothouse of Zydeco Gary Hartman Roger Wood

et al.: Contents Letter from the Director As the Institute for riety of other great Texas musicians. Proceeds from the CD have the History of Texas been vital in helping fund our ongoing educational projects. Music celebrates its We are very grateful to the musicians and to everyone else who second anniversary, we has supported us during the past two years. can look back on a very The Institute continues to add important new collections to productive first two the Texas Music Archives at SWT, including the Mike Crowley years. Our graduate and Collection and the Roger Polson and Cash Edwards Collection. undergraduate courses We also are working closely with the Texas Heritage Music Foun- on the history of Texas dation, the Center for American History, the Texas Music Mu- music continue to grow seum, the New Braunfels Museum of Art and Music, the Mu- in popularity. The seum of American Music History-Texas, the Mexico-North con- Handbook of Texas sortium, and other organizations to help preserve the musical Music, the definitive history of the region and to educate the public about the impor- encyclopedia of Texas tant role music has played in the development of our society. music history, which we At the request of several prominent people in the Texas music are publishing jointly industry, we are considering the possibility of establishing a music with the Texas State Historical Association and the Texas Music industry degree at SWT. This program would allow students Office, will be available in summer 2002. The online interested in working in any aspect of the music industry to bibliography of books, articles, and other publications relating earn a college degree with specialized training in museum work, to the history of Texas music, which we developed in cooperation musical performance, sound recording technology, business, with the Texas Music Office, has proven to be a very useful tool marketing, promotions, journalism, or a variety of other sub- for researchers. -

Convention Grade 7

Texas Historical Commission Washington-on-the-Brazos A Texas Convention Grade 7 Virtual Field Trip visitwashingtononthebrazos.com Learning Guide Grade 7 Childhood in the Republic Overview: A New Beginning for Texas Texas became Mexican territory in 1821 and the new settlers brought by Stephen F. Austin and others were considered Mexican citizens. The distance between the settlements and Mexico (proper), plus the increasing number of settlers moving into the territory caused tension. The settlers had little influence in their government and limited exposure to Mexican culture. By the time of the Convention of 1836, fighting had already Image “Reading of the Texas Declaration of broken out in some areas. The causes of some of this Independence,” Courtesy of Artie Fultz Davis Estate; Artist: Charles and Fanny Norman, June 1936 fighting were listed as grievances in the Texas Declaration of Independence. Objectives • Identify the key grievances given by the people of Texas that lead to the formation of government in the independent Republic of Texas • How do they compare to the grievances of the American Revolution? • How do they relate to the Mexican complaints against Texas? • How did these grievances lead to the formation of government in the Republic? • Identify the key persons at the Convention of 1836 Social Studies TEKS 4th Grade: 4.3A, 4.13A 7th Grade: 7.1 B, 7.2 D, 7.3C Resources • Activity 1: 59 for Freedom activity resources • Activity 2: Declaration and Constitution Causes and Effects activity resources • Extension Activity: Order -

Winter Arrives with a Wallop

weather Monday: Showers, high 42 degrees monday Tuesday: Partly cloudy, high 42 degrees Wednesday: Rain likely, high in the low 40s THE ARGO Thursday: Rain likely , high in the upper 30s Volume 58 Friday: Chance of rain , high in the low 30s of the Richard Stockton College Number 1 Serving the college community since 1973 m ihh Winter arrives with a wallop Dan G rote ed to engage in snowball fights The Argo despite or perhaps in spite of the decree handed down by the Much like the previous semes- Office of Housing and ter, when Hurricane Floyd barked Residential Life, which stated at Stockton, the new semester has that snowball fighters can expect begun with weather-related can- a one hundred dollar fine and loss cellations. In the past two weeks, of housing. four days of classes have seen One freshman, Bob Atkisson, cancellations, delayed openings, expressed his outrage at the and early closings. imposed rule. "I didn't think we Snowplows have crisscrossed should get fined for throwing the campus, attempting to keep snowballs. I went to LaSalle a the roads clear, while at the same couple days ago, and they actual- time blocking in the cars of resi- ly scheduled snowball fights dents, some of whom didn't real- there." ly seem to mind. Though many students were Optimistic students glued heard grumbling over having to themselves to channel 2 in hopes dig their cars out of the snow due of not having to go to their 8:30 to the plowing, they acknowl- classes, while others called the edged that plant management did campus hotline (extension 1776) an excellent job keeping for word of the same. -

16 Artist Index BILLJ~OYD (Cont'd) Artist Index 17 MILTON BROWN

16 Artist Index Artist Index 17 BILLJ~OYD (cont'd) MILTON BROWN (cont'd) Bb 33-0501-B 071185-1 Jennie Lou (Bill Boyd-J.C. Case)-1 82800-1 071186-1 Tumble Weed Trail (featured in PRC film "Tumble Do The Hula Lou (Dan Parker)-1 Bb B-5485-A, Weed Trail") (Bill Boyd-Dick Reynolds)-1 Bb B-9014-A MW M-4539-A, 071187-1 Put Your Troubles Down The Hatch (Bill Boyd• 82801-1 M-4756-A Marvin Montgomery) -3 Bb 33-0501-A Garbage Man Blues (Dan Parker) -1,3 Bb B-5558-B, 071188-1 Home Coming Waltz Bb B-890Q-A, 82802-1 MWM-4759-A RCA 2Q-2069-A Four, Five Or Six Times (Dan Parker) -1,3* Bb B-5485-B, 071189-1 Over The Waves Waltz (J. Rosas) Bb B-8900-B, MW M-4539-B, RCA 2Q-2068-B M-4756-B Reverse of RCA 2Q-2069 is post-war Bill Boyd title. First pressings of Bb B-5444 were issued as by The Fort Worth Boys with "Milton Brown & his Musical Brownies" in parentheses. On this issue, co-writer for "Oh You Pretty Woman" is listed as Joe Davis. 1937 issues of 82801 ("staff' Bluebird design) list title as "Garage Man Blues." JIM BOYD & AUDREY DAVIS (The Kansas Hill Billies) September 30, 1934; Fort Worth, Texas August 8, 1934; Texas Hotel, San Antonio, Texas. Jim Boyd, guitarllead vocal; Audrey Davis, fiddle/harmony vocal. Milton Brown, vocal-1; Cecil Brower, fiddle; Derwood Brown, guitar/vocal-2; Fred "Papa" Calhoun, piano; Wanna Coffman, bass; Ted Grantham, fiddle; Ocie Stockard, tenor banjo; Band backing vocal -3. -

Culture, Recreation and Tourism

Interim Report to the 85th Texas Legislature House Committee on Culture, Recreation & Tourism January 2017 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON CULTURE, RECREATION, & TOURISM TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERIM REPORT 2016 A REPORT TO THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 85TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE RYAN GUILLEN CHAIRMAN COMMITTEE CLERK BEN WRIGHT Committee On Culture, Recreation, & Tourism JanuaryJanuary 10,4, 2017 2017 Ryan Guillen P.O. Box 2910 Chairman Austin, Texas 78768-2910 The Honorable Joe Straus Speaker, Texas House of Representatives Members of the Texas House of Representatives Texas State Capitol, Rm. 2W.13 Austin, Texas 78701 Dear Mr. Speaker and Fellow Members: The Committee on Culture, Recreation, & Tourism of the Eighty-fourth Legislature hereby submits its interim report including recommendations and drafted legislation for consideration by the Eighty-fifth Legislature. Respectfully submitted, _______________________ Ryan Guillen _______________________ _______________________ Dawnna Dukes, Vice Chair John Frullo _______________________ _______________________ Lyle Larson Marisa Márquez _______________________ _______________________ Andrew Murr Wayne Smith Dawnna Dukes Vice-Chairman Members: John Frullo, Lyle Larson, Marisa Márquez, Andrew Murr, Wayne Smith TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 6 CULTURE, RECREATION, & TOURISM ................................................................................... 7 Interim Charge #1 ........................................................................................................................ -

Book Review:" We're the Light Crust Doughboys from Burrus Mill": An

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2005 Book Review: "We're The Light Crust Doughboys from Burrus Mill": An Oral History Kevin Coffey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Coffey, Kevin, "Book Review: "We're The Light Crust Doughboys from Burrus Mill": An Oral History" (2005). Great Plains Quarterly. 165. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/165 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 264 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, FALL 200S is the more substantial and successful of the two new books. Boyd's is far narrower in scope-its main text weighs in at only 121 pages-as well as less accurate and less colorfully told. The Jazz of the Southwest was characterized by an alarming lack of scholarly vigor, and that same defect pervades the newer work. Problems arise from the start. The opening chapter on various strains of Texas music is perfunctory, distilled from a few extremely general texts (or Web sites); it offers little insight into the musi cal and social milieu from which the Doughboys "We're The Light Crust Doughboys from Burrus and their music sprang. Once Boyd delves into Mill": An Oral History. By Jean Boyd. Austin: the band's history proper, errors-some small, University of Texas Press, 2003. -

San Antonio's West Side Sound

Olsen: San Antonio's West Side Sound San Antonio’s SideSound West Antonio’s San West Side Sound The West Side Sound is a remarkable they all played an important role in shaping this genre, Allen O. Olsen amalgamation of different ethnic beginning as early as the 1950s. Charlie Alvarado, Armando musical influences found in and around Almendarez (better known as Mando Cavallero), Frank San Antonio in South-Central Texas. It Rodarte, Sonny Ace, Clifford Scott, and Vernon “Spot” Barnett includes blues, conjunto, country, all contributed to the creation of the West Side Sound in one rhythm and blues, polka, swamp pop, way or another. Alvarado’s band, Charlie and the Jives, had such rock and roll, and other seemingly regional hits in 1959 as “For the Rest of My Life” and “My disparate styles. All of these have Angel of Love.” Cavallero had an influential conjunto group somehow been woven together into a called San Antonio Allegre that played live every Sunday sound that has captured the attention of morning on Radio KIWW.5 fans worldwide. In a sense, the very Almendarez formed several groups, including the popular eclectic nature of the West Side Sound rock and roll band Mando and the Chili Peppers. Rodarte led reflects the larger musical environment a group called the Del Kings, which formed in San Antonio of Texas, in which a number of ethnic during the late 1950s, and brought the West Side Sound to Las communities over the centuries have Vegas as the house band for the Sahara Club, where they exchanged musical traditions in a remained for nearly ten years.6 Sonny Ace had a number of prolific “cross-pollination” of cultures. -

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM Holden Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.1 3.0 English Fiction 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea Jon Buller LG 2.6 0.5 English Fiction 11592 2095 Jon Scieszka MG 4.8 2.0 English Fiction 6201 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen LG 3.1 2.0 English Fiction 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola LG 4.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 166 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson MG 5.2 5.0 English Fiction 9001 The 500 Hats of Bartholomew CubbinsDr. Seuss LG 3.9 1.0 English Fiction 413 The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson MG 4.3 2.0 English Fiction 11151 Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner LG 2.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 61248 Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved BooksKay Winters LG 3.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 101 Abel's Island William Steig MG 6.2 3.0 English Fiction 13701 Abigail Adams: Girl of Colonial Days Jean Brown Wagoner MG 4.2 3.0 English Nonfiction 9751 Abiyoyo Pete Seeger LG 2.8 0.5 English Fiction 907 Abraham Lincoln Ingri & Edgar d'Aulaire 4.0 1.0 English 31812 Abraham Lincoln (Pebble Books) Lola M. Schaefer LG 1.5 0.5 English Nonfiction 102785 Abraham Lincoln: Sixteenth President Mike Venezia LG 5.9 0.5 English Nonfiction 6001 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith LG 5.0 3.0 English Fiction 102 Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt MG 8.9 11.0 English Fiction 7201 Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg LG 1.2 0.5 English Fiction 17602 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie:Kristiana The Oregon Gregory Trail Diary..