1939-1940 a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in Partial Fulf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hay Any Work for Cooper 1 ______

MARPRELATE TRACTS: HAY ANY WORK FOR COOPER 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ Hay Any Work For Cooper.1 Or a brief pistle directed by way of an hublication2 to the reverend bishops, counselling them if they will needs be barrelled up3 for fear of smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state, that they would use the advice of reverend Martin for the providing of their cooper. Because the reverend T.C.4 (by which mystical5 letters is understood either the bouncing parson of East Meon,6 or Tom Cook's chaplain)7 hath showed himself in his late Admonition To The People Of England to be an unskilful and beceitful8 tub-trimmer.9 Wherein worthy Martin quits himself like a man, I warrant you, in the modest defence of his self and his learned pistles, and makes the Cooper's hoops10 to fly off and the bishops' tubs11 to leak out of all cry.12 Penned and compiled by Martin the metropolitan. Printed in Europe13 not far from some of the bouncing priests. 1 Cooper: A craftsman who makes and repairs wooden vessels formed of staves and hoops, as casks, buckets, tubs. (OED, p.421) The London street cry ‘Hay any work for cooper’ provided Martin with a pun on Thomas Cooper's surname, which Martin expands on in the next two paragraphs with references to hubs’, ‘barrelling up’, ‘tub-trimmer’, ‘hoops’, ‘leaking tubs’, etc. 2 Hub: The central solid part of a wheel; the nave. (OED, p.993) 3 A commodity commonly ‘barrelled-up’ in Elizabethan England was herring, which probably explains Martin's reference to ‘smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state’. -

Sault Tribe Receives $2.5M Federal HHS Grant Tribe Gets $1.63 Million

In this issue Recovery Walk, Pages 14-15 Tapawingo Farms, Page 10 Squires 50th Reunion, Page 17 Ashmun Creek, Page 23 Bnakwe Giizis • Falling Leaves Moon October 7 • Vol. 32 No. 10 Win AwenenOfficial newspaper of the SaultNisitotung Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians Sault Tribe receives $2.5M federal HHS grant The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of diseases such as diabetes, heart tobacco-free living, active living blood pressure and high choles- visit www.healthysaulttribe.net. Chippewa Indians is one of 61 disease, stroke and cancer. This and healthy eating and evidence- terol. Those wanting to learn more communities selected to receive funding is available under the based quality clinical and other To learn more about Sault Ste. about Community Transformation funding in order to address tobac- Affordable Care Act to improve preventive services, specifically Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians’ Grants, visit www.cdc.gov/com- co free living, active and healthy health in states and communities prevention and control of high prevention and wellness projects, munitytransformation. living, and increased use of high and control health care spending. impact quality clinical preventa- Over 20 percent of grant funds tive services across the tribe’s will be directed to rural and fron- seven-county service area. The tier areas. The grants are expected U.S. Department of Health and to run for five years, with projects Human Services announced the expanding their scope and reach grants Sept. 27. over time as resources permit. The tribe’s Community Health According to Hillman, the Sault Department will receive $2.5 mil- Tribe’s grant project will include lion or $500,000 annually for five working with partner communities years. -

Jrnuhl00fren.Pdf

OAK ST. HDSF UNDERGRADUATE LIBRARY, The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library L161 O-1096 JORN UHL JORN UHL BY GUSTAV FRENSSEN TRANSLATED BY F. S. D ELMER ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE AND COMPANY, LTD. 1905 Edinburgh : T. and A. CONSTABLE, Printers to His Majesty - I F 8 g 7 HOST s 2 A PREFATORY NOTE GUSTAV FRENSSEN, the author of Jorn Uhl, was born in the J =3 remote village of Barlt, in Holstein, North Germany, on October 19, 1863. His father is a carpenter in this village, and, according to the church register, the Frenssen family has lived there as long as ever such records have been kept in the parish. In spite of his father's humble circumstances, Gustav Frenssen managed to attend the Latin School at the neighbouring town of Husum, and in due time became a student of theology. He heard courses of lectures at various Universities, passed the necessary examinations, and finally, -after long years of waiting, was appointed to the care of souls in the little Lutheran pastorate of Hemme in Holstein. Here within sound of the North Sea, and under the mossy thatch of the old-fashioned manse, he wrote his first two books, Die Sandgrafin and Die drei Getreuen. These two novels remained almost unknown until after the publication of Jorn Uhl in 1902. This book took Germany by storm. -

Inside Facts of Stage and Screen (February 7, 1931)

STAGE PRICE lO CENTS RADIO SCREEN Only Theatrical MUSIC Newspaper on the Pacific Coast j EDITED BY JACK JOSEPHS ESTABLISHED 1924 Entered Vol. XIII as Second Class Matter, April 29, 1927, at Post- office, Los. Angeles, Calif., Published Every Saturday at 809 Warner Bros Down- under Act ’ Saturday, of March 3, 1879 February 7, 1931 town Building. 401 West Seventh St., Los Angeles, Calif. No. 5 PLAN ‘JITNEY THEATRE’ CHAIN FOR PAC. COAST +- Press and MX Group Show Biz To Finance In Clash 10c Houses ' A war which has been , brewing leaf theatre ween local interests and A chain of miniature theatres, of the local press was all set to break two hundred seating capacity and oqt in dead earnest this week. to operate on a 10 cents admission Illustrated The Los Angeles schedule, is planned by a Nip-tY. -"k Daily, News, a morning- tabloid, orgr’fization which ha? fired broadside • • a into show busi- sodufcs on the toa-on. ove ness under a five-column line on prospects for nikiatiiifc Jha.., of page 2 their Thursday editions, here. panning the gala premiere policy to a fare-ye-well. While the News The plan is to spot the houses in shot was particularly at the pre- class picture neighborhoods, play- miere of RKO’s “Cimarron” at the ing opposition to the 65 centers and Orpheum Theatre, it was a crack relying for their draw on the smaii at the whole premiere practice. admission fee. ' Info from inside the battle lines, The program will be a feature, a coupled up with the fact that the comedy and a newsreel. -

Country, House, Fiction Kristen Kelly Ames

Conventions Were Outraged: Country, House, Fiction Kristen Kelly Ames A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO June 2014 © Kristen Kelly Ames, 2014 ii ABSTRACT The dissertation traces intersections among subjectivity, gender, desire, and nation in English country house novels from 1921 to 1949. Inter-war and wartime fiction by Daphne du Maurier, Virginia Woolf, Nancy Mitford, P. G. Wodehouse, Elizabeth Bowen, and Evelyn Waugh performs and critiques conventional domestic ideals and, by extension, interrupts the discourses of power that underpin militaristic political certainties. I consider country house novels to be campy endorsements of the English home, in which characters can reimagine, but not escape, their roles within mythologized domestic and national spaces. The Introduction correlates theoretical critiques of nationalism, class, and gender to illuminate continuities among the naïve patriotism of the country house novel and its ironic figurations of rigid class and gender categories. Chapter 1 provides generic and critical contexts through a study of du Maurier’s Rebecca, in which the narrator’s subversion of social hierarchies relies upon the persistence, however ironic, of patriarchal nationalism. That queer desire is the necessary center around which oppressive norms operate only partially mitigates their force. Chapter 2 examines figures of absence in “A Haunted House,” To the Lighthouse, and Orlando. Woolf’s queering of the country house novel relies upon her Gothic figuration of Englishness, in which characters are only included within nationalist spaces by virtue of their exclusion. -

These Strange Criminals: an Anthology Of

‘THESE STRANGE CRIMINALS’: AN ANTHOLOGY OF PRISON MEMOIRS BY CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS FROM THE GREAT WAR TO THE COLD WAR In many modern wars, there have been those who have chosen not to fight. Be it for religious or moral reasons, some men and women have found no justification for breaking their conscientious objection to vio- lence. In many cases, this objection has lead to severe punishment at the hands of their own governments, usually lengthy prison terms. Peter Brock brings the voices of imprisoned conscientious objectors to the fore in ‘These Strange Criminals.’ This important and thought-provoking anthology consists of thirty prison memoirs by conscientious objectors to military service, drawn from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and centring on their jail experiences during the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War. Voices from history – like those of Stephen Hobhouse, Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, Ian Hamilton, Alfred Hassler, and Donald Wetzel – come alive, detailing the impact of prison life and offering unique perspectives on wartime government policies of conscription and imprisonment. Sometimes intensely mov- ing, and often inspiring, these memoirs show that in some cases, indi- vidual conscientious objectors – many well-educated and politically aware – sought to reform the penal system from within either by publicizing its dysfunction or through further resistance to authority. The collection is an essential contribution to our understanding of criminology and the history of pacifism, and represents a valuable addition to prison literature. peter brock is a professor emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Toronto. -

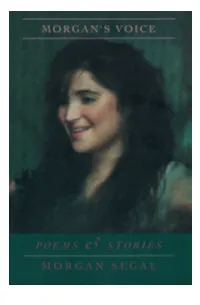

Get a PDF Copy of Morgan's Voice

Morgan's Voice POEMS& STORIES Morgan Segal Copyright © 1997 by RobertSegal All rights reserved. Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data Segal,Morgan Morgan's Voice Poems8c Stories ISBN 0-9662027-0-8 First Edition 1997 Designedby RileySmith Printed in the United Statesof America by PacificRim Printers/Mailers 11924 W. Washington Blvd. LosAngeles, CA 90066 Printed on acid-free, recycled paper. The gift of sharing so intimately in Morgan's life, through her prose and poetry, is one all will commit to their hearts. Here are remembrances, emotionally inspired, of personal journeys through a landscape of experience that has been both tranquil and turbulent. Her poems are "pearls dancing," shimmering like her own life in an all too brief sunlight; her stories portraits, at times fragile, at times triumphant in their will to witness lasting humaness. She is tmly a talent and a presence too soon lost. -James Ragan, Poet Director, Professional Writing Program University of Southern California Morgan possessed a rare and beautiful soul. Those wide brown eyes of hers shone forth with a child's curiosity and innocence. But her heart was the heart of woman who was haunted by unfathomable darkness. Morgan's words are infused with depth, wisdom, honesty, courage and insight. Her descriptions reveal the intense thirst she had for even the most mundane aspects of life -- a fingernail, the scale of a fish, a grandfather's breath, a strand of hair. The attention she pays to details can help us to return to our lives with a renewed revereance for all the subtle miracles that surround us each moment. -

The Haunted Seas of British Television: Nation, Environment and Horror

www.gothicnaturejournal.com Gothic Nature ________________________________________________________________ Gothic Nature II How to Cite: Fryers, M. (2021) The Haunted Seas of British Television: Nation, Environment and Horror. Gothic Nature. 2, pp. 131-155. Available from: https://gothicnaturejournal.com/. Published: March 2021 ________________________________________________________________ Peer Review: All articles that appear in the Gothic Nature journal have been peer reviewed through a fully anonymised process. Copyright: © 2021 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Gothic Nature is a peer-reviewed open-access journal. www.gothicnaturejournal.com Cover credit: Model IV, 2017 Artist: D Rosen Cast Aluminum (Original Objects: Buck Antler and Stomach (Decorative Model), Camel Mask (Theatrical Model), Whip (Didactic Model), Stiletto (Decoy Model), Goose Neck (Decoy Model), Nylons, Bra Underwire, Calvin Klein Dress, Facial Mask, Necklace, Wax 21 x 25 x 12 in. Photo credit: Jordan K. Fuller Fabrication: Chicago Crucible Web Designer: Michael Belcher www.gothicnaturejournal.com The Haunted Seas of British Television: Nation, Environment and Horror Mark Fryers ABSTRACT Historically, the sea holds symbolic power within British culture, a space of imperial triumph and mastery over nature. The British coastline, similarly, has served as both a secure defence and a space of freedom and abandonment. However, since the decline of both the empire and the maritime industries, these certainties have eroded, along with the physical coastline itself. -

A Gilded Cage: a Feminist Analysis of Manor House Literature Katelyn Billings Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2016 A Gilded Cage: A Feminist Analysis of Manor House Literature Katelyn Billings Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Billings, Katelyn, "A Gilded Cage: A Feminist Analysis of Manor House Literature" (2016). Honors Theses. 121. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/121 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Gilded Cage: A Feminist Analysis of Manor House Literature By Katelyn Billings ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of English UNION COLLEGE April, 2016 Abstract: This thesis focuses on women struggling with social rules and gender restrictions in Victorian and Edwardian English manor houses. The culture of the manor home had an incredibly powerful impact on the female protagonists of the literary texts I analyze, and in this thesis, I demonstrate how it stifled the growth and agency of women. With the end of the age of the British Great Houses in the twentieth century, there was the simultaneous rise of the New Woman, an emerging cultural icon that challenged conservative Victorian conventions. With the values and ideologies surrounding the New Woman in mind, this thesis analyzes the protagonists of Jane Eyre, Howards End and Rebecca in order to present the infiltration of the New Woman in the Great House genre, and how she brought about its end. -

Maxim De Winter's Perception of the Female World in Du Maurier's Rebecca

University of Business and Technology in Kosovo UBT Knowledge Center UBT International Conference 2018 UBT International Conference Oct 27th, 1:30 PM - 3:00 PM Maxim de Winter’s perception of the female world in Du Maurier’s Rebecca Silvishah Miftari Goodspeed Nova International School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecenter.ubt-uni.net/conference Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Goodspeed, Silvishah Miftari, "Maxim de Winter’s perception of the female world in Du Maurier’s Rebecca" (2018). UBT International Conference. 128. https://knowledgecenter.ubt-uni.net/conference/2018/all-events/128 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Publication and Journals at UBT Knowledge Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in UBT International Conference by an authorized administrator of UBT Knowledge Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maxim de Winter’s Perception of the Female World in Du Maurier’s Rebecca Silvishah Miftari Goodspeed Nova International Schools, Skopje [email protected] Abstract. Rebecca is a novel written by Daphne Du Maurier, in which the main characters are women. This paper focuses on the only male point of view, Maxim de Winter’s. He was Rebecca’s husband and he is the spouse of the current Mrs. de Winter. He is also Mrs. Danvers’ landlord, Beatrice’s brother, and Mrs. Van Hopper’s acquaintance. He is the lynchpin uniting the female characters, whose decisive leadership motivates the novel’s action. In the past, critics have often analyzed the plot’s female points of view, mentioning Mr. -

Manderley: a House of Mirrors; the Reflections of Daphne Du Maurier’S Life in Rebecca

Manderley: a House of Mirrors; the Reflections of Daphne du Maurier’s Life in Rebecca by Michele Gentile Spring 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English in cursu honorum Reviewed and approved by: Dr. Kathleen Monahan English Department Chair _______________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor Submitted to the Honors Program, Saint Peter's University 17, March 2014 Gentile2 Table of Contents Dedication…………………………………………………………………………..3 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...3 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..4 Introduction………………………………………………………………………...5 Chapter I: The Unnamed Narrator………………………………………………….7 Chapter II: Rebecca……………………………………………………………….35 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………...54 Works Cited Page…………………………………………………………………55 Gentile3 Dedication: I would like to dedicate this paper to my parents, Tom and Joann Gentile, who have instilled the qualities of hard work and dedication within me throughout my entire life. Without their constant love and support, this paper would not have been possible. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Monahan for serving as my advisor during this experience and for introducing me to Daphne du Maurier‟s literature. Dr. Monahan, your assistance has made this process much less overwhelming and significantly more enjoyable. I would also like to thank Doris D‟Elia in assisting me with my research for this paper. Doris, your help allowed me to enjoy writing this paper, rather than fearing the research I needed to conduct. Gentile4 Abstract: Daphne du Maurier lived an unconventional life in which she rebelled against the standards society had set in place for a woman of her time. Du Maurier‟s inferiority complex, along with her incestuous feelings and bisexuality, set the stage for the characters and events in her most famous novel, Rebecca. -

Ellis & Associates, Inc

INTERNATIONAL LIFEGUARD Training Program Manual 5th Edition Meets ECC, MAHC, and OSHA Guidelines Ellis & Associates, Inc. 5979 Vineland Rd. Suite 105 Orlando, FL 32819 www.jellis.com 800-742-8720 Copyright © 2020 by Ellis & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated in writing by Ellis & Associates, the recipient of this manual is granted the limited right to download, print, photocopy, and use the electronic materials to fulfill Ellis & Associates lifeguard courses, subject to the following restrictions: • The recipient is prohibited from downloading the materials for use on their own website. • The recipient cannot sell electronic versions of the materials. • The recipient cannot revise, alter, adapt, or modify the materials. • The recipient cannot create derivative works incorporating, in part or in whole, any content of the materials. For permission requests, write to Ellis & Associates, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address above. Disclaimer: The procedures and protocols presented in this manual and the course are based on the most current recommendations of responsible medical sources, including the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) Consensus Guidelines for CPR, Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) and First Aid, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards 1910.151, and the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC). The materials have been reviewed by internal and external field experts and verified to be consistent with the most current guidelines and standards. Ellis & Associates, however, make no guarantee as to, and assume no responsibility for, the correctness, sufficiency, or completeness of such recommendations or information. Additional procedures may be required under particular circumstances. Ellis & Associates disclaims all liability for damages of any kind arising from the use of, reference to, reliance on, or performance based on such information.