Working at Play: the Phenomenon of 19Th Century Worker-Competitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAA Tourney Notes Stanford.Indd

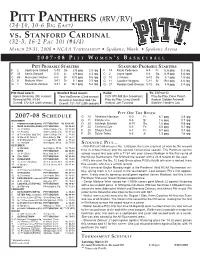

(#RV/RV) PITT PANTHERS (24-10, 10-6 BIG EAST) VS. STANFORD CARDINAL (32-3, 16-2 PAC 10) (#4/4) MARCH 29-31, 2008 • NCAA TOURNAMENT • Spokane, Wash. • Spokane Arena 22007-080 0 7 - 0 8 P IITTT T W OOMENM E N ’ S B AASKETBALLS K E T B A L L PITT PROBABLE STARTERS STANFORD PROBABLE STARTERS F 2 Sophronia Sallard 5-10 So. 2.9 ppg 2.5 rpg F 14 Kayla Pedersen 6-4 Fr. 12.6 ppg 8.3 rpg F 33 Xenia Stewart 6-0 Jr. 8.9 ppg 4.3 rpg C 2 Jayne Appel 6-4 So. 14.9 ppg 8.8 rpg C 45 Marcedes Walker 6-3 Sr. 13.9 ppg 9.6 rpg G 10 JJ Hones 5-10 So. 6.1 ppg 1.9 rpg G 0 Mallorie Winn 5-11 Sr. 8.1 ppg 3.5 rpg G 11 Candice Wiggins 5-11 Sr. 19.8 ppg 4.6 rpg G 1 Shavonte Zellous 5-11 Jr. 18.1 ppg 5.4 rpg G 21 Rosalyn Gold-Onwude 5-10 So. 4.9 ppg 2.4 rpg Pitt Head Coach: Stanford Head Coach: Radio: TV: ESPN2HD Agnus Berenato (5th season) Tara VanDerveer (22nd season) FOX 970 AM (live broadcast) Play-by-Play: Dave Pasch Record at Pitt: 89-64 Record at Stanford: 569-136 Play-by-Play: Greg Linnelli Analyst: Debbie Antonelli Overall: 372-328 (24th season) Overall: 721-187 (29th season) Analyst: Jen Tuscano Sideline: Heather Cox PITT OFF THE BENCH 2007-08 SCHEDULE G 10 Taneisha Harrison 6-0 Fr. -

Game Notes.Pmd

PITT BASKETBALL FLORIDA STATE • JANUARY 14, 2014 • PETERSEN EVENTS CENTER • PITTSBURGH, PA. 2014-15 SCHEDULE Date Opponent W/L Time GAME FLORIDA STATE (9-7, 1-2 ACC) O31 INDIANA, PA (Exh.) W 72-58 N7 PHILADELPHIA (Exh.) W 82-71 at PITT (11-5, 1-2 ACC) N14 NIAGARA (ESPN3) W 78-45 17 EA Sports Maui Invitational (Pittsburgh, Pa.) N16 SAMFORD (RSN/Root) W 63-56 Wednesday, January 14, 2015 • 9 p.m. ET N21 at Hawaii L 74-70 Petersen Events Center (12,508) • Pittsburgh, Pa. EA Sports Maui Invitational (Maui, Hawaii) N24 vs. Chaminade (ESPNU) W 81-68 N25 vs. San Diego State (ESPN) L 74-57 TV: RSN/Root Sports in Pittsburgh (Tom Werme and Bobby Cremins; Producer: Ken Neal). N26 vs. Kansas State (ESPN2) W 70-47 Pitt Radio: 20 affiliates of the Pitt IMG Sports Radio Network (Bill Hillgrove, Dick Groat, Curtis Aiken). 93.7 The Fan, 93.7 FM in Pittsburgh; Satellite Radio: Sirius 132; XM: 193 (Pitt feeds). ACC/Big Ten Challenge D2 at Indiana (ESPN2) L 81-69 Internet Radio Broadcast/Live Stats: www.pittsburghpanthers.com. Coaches: Pitt: Jamie Dixon, 16th year at Pitt, 12th year as head coach (299-101); D5 vs. Duquesne (ESPN3) W 76-62 Florida State: Leonard Hamilton, 13th year at FSU (228-164), 28th year overall (428-374). D13 ST. BONAVENTURE (ESPNU) W 58-54 Rankings: Pitt: AP-NR; USA Today-NR; Florida State: AP-NR; USA Today-NR. D17 MANHATTAN (ESPN3) W 65-56 Series: Pitt and Florida State meet for the 12th time in series history. -

Anglo-American Blood Sports, 1776-1889: a Study of Changing Morals

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1974 Anglo-American blood sports, 1776-1889: a study of changing morals. Jack William Berryman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Berryman, Jack William, "Anglo-American blood sports, 1776-1889: a study of changing morals." (1974). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1326. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1326 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLO-AMERICAN BLOOD SPORTS, I776-I8891 A STUDY OF CHANGING MORALS A Thesis Presented By Jack William Berryman Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS April, 197^ Department of History » ii ANGLO-AMERICAN BLOOD SPORTS, 1776-1889 A STUDY OF CHANGING MORALS A Thesis By Jack V/illiam Berryman Approved as to style and content by« Professor Robert McNeal (Head of Department) Professor Leonard Richards (Member) ^ Professor Paul Boyer (I'/iember) Professor Mario DePillis (Chairman) April, 197^ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Upon concluding the following thesis, the many im- portant contributions of individuals other than myself loomed large in my mind. Without the assistance of others the project would never have been completed, I am greatly indebted to Professor Guy Lewis of the Department of Physical Education at the University of Massachusetts who first aroused my interest in studying sport history and continued to motivate me to seek the an- swers why. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_November 2, 2007__ I, __Aaron Cowan___________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: A Nice Place to Visit: Tourism, Urban____________ Revitalization, and the Transformation of Postwar American Cities This work and its defense approved by: David Stradling, Chair: ___David Stradling______________ Wayne Durrill __ Wayne Durrill_____ ________ Tracy Teslow ___Tracy Teslow _______________ Marguerite Shaffer Marguerite Shaffer Miami University Oxford, Ohio A Nice Place To Visit: Tourism, Urban Revitalization, and the Transformation of Postwar American Cities A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Aaron B. Cowan M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2003 B.A., King College, 1999 Committee Chair: Dr. David Stradling Abstract This dissertation examines the growth of tourism as a strategy for downtown renewal in the postwar American city. In the years after World War II, American cities declined precipitously as residents and businesses relocated to rapidly-expanding suburbs. Governmental and corporate leaders, seeking to arrest this decline, embarked upon an ambitious program of physical renewal of downtowns. The postwar “urban crisis” was a boon for the urban tourist industry. Finding early renewal efforts ineffective in stemming the tide of deindustrialization and suburbanization, urban leaders subsidized, with billions of dollars in public finances, the construction of an infrastructure of tourism within American downtowns. By the latter decades of the period, tourist development had moved from a relatively minor strategy for urban renewal to a key measure of urban success. -

The History and Influence of Black Baseball in the United States and Indianapolis

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 3-29-1991 The History and Influence of Black Baseball in the United States and Indianapolis Scott Clayton Bower Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Bower, Scott Clayton, "The History and Influence of Black Baseball in the United States and Indianapolis" (1991). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 62. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/62 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Applicant Scott Clayton Bower (Name as it is to appear on diploma) Thesis titIe The His torvandInflu e nee 0 f B1a c k 8 asp b all i Q t-he Un i ted S tate sandIn d iana pol i 5 Department ormajor Departmen t---oT Hi 5 tor V Level of Honors sought: General MaQna CIJm I allde Departmental _ Intended date of commence....rnAft_...+ 0 e c em b e r 1 9 91 --=-=:....:....::~-=-=--..:..-.:::....:.:.....:.....-_------- JelilMr"'" q/ :Ittl'ate' d Honors Committee . pJ . _ - I 11/{/ ~ )/!//y> Date Accepted and certified to Registrar: ~velflL@u 1f!~(Cff( 'ate -

We're from the Town with the Great Football Team

WE‟RE FROM THE TOWN WITH THE GREAT FOOTBALL TEAM: A PITTSBURGH STEELERS MANIFESTO By David Villiotti June 2009 1 To… Idie, Anthony & “Mrs. Swiss” ...tolerating my mania Tony …infecting me with Steelers Fever Mom …see Line 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Preface 4 January, 2008 7 Behind Enemy Lines 8 Family of Origin…Swissvale 13 The Early Years: Pitt Stadium Days 18 Forbes Field Memories 28 Other Burgh Sports 34 Tony 38 Rest of The Boys 43 1970s: Unparallelled 46 Why Roy Gerela 64 1980s: Dark Decade 68 Why Mrs. Swiss Hates the Steelers 79 Stuff I Hate about the NFL 83 „90s: Changing of the Guard 87 Heckling 105 Family Gatherings 108 Taping 111 Rooting for Injuries 115 13 Minutes Ain‟t Enuff 120 Y2K Decade: First Five Years…Still Waiting 124 One For The Thumb 133 Cowher Out…Tomlin In 140 Steelers Trivia Challenge 145 Steelers Sites: Mill, Fury, Spiker, et al 149 Six!!! 156 City of Champions 209 Closing 214 *From “The Steelers Polka” by Jimmy Psihoulis 3 PREFACE Having catalogued my life by the ups and downs of the Pittsburgh Steelers Football Club, and having surpassed the half century mark in age, I endeavored to author a memoir of my life as a fan. This perhaps would be suited for a time capsule for my children, or alternatively as a project for a publisher whose business was really, really slow. For the past few years, I‟ve written a number of articles, under the screen name, Swissvale72 for a few Pittsburgh Steelers related websites, most notably, and of longest duration, was an association with Stillers.com, prior to my falling into disfavor with management. -

From a Small Group of Bulldog Believers to Sellout Crowds

ESTABLISHED 1879 | COLUMBUS, MISSISSIPPI C DISPATCH.COM FREE! FRIDAY | MARCH 30, 2018 GROWING THE CHOIR Kelly Price/MSU Athletic Media Relations Mississippi State’s women’s basketball team huddles up during a practice in the Nationwide Arena in Columbus, Ohio, in preparation for its Final Four match-up against Louisville. The Bulldogs will face the Cardinals at 6 p.m. for a shot to return to the national title game. From a small group of Bulldog believers to sellout crowds, women’s basketball sees boom in fan support MSU faces Louisville tonight for berth in national title game From left, Tommy and BDMY A A MINICHINO Terri Nusz, Brad Brad- [email protected] way, David Hunt, and former Mississippi COLUMBUS, Ohio — It didn’t take long for Tommy State women’s bas- Nusz to get to know Vic Schaefer. ketball coach Sharon Asked by then Mississippi State Director of Athletics Fanning-Otis and her husband, Larry Otis, are Scott Stricklin to meet Schaefer, Nusz spent about half part of a group of core of the free time at the August Road Dawgs Tour stop fans that has traveled to in 2012 in Houston, Texas, talking to Vic and his wife, follow the MSU women’s Holly. basketball team since “He is clearly passionate. He is infectious,” Nusz said. coach Vic Schaefer was “He is very persuasive.” hired in 2012. They Nusz said Schaefer communicated his vision for the will cheer the team on tonight against Louisville MSU women’s basketball program and outlined what in the national semifi- he needed to help the program reach the highest level. -

Views Expressed Here May Not Apply to All Students and All Department. It Is Meant to Give Students a General Idea and ANKUR Cannot Be Held Responsible in Any Event

Disclaimer: All views expressed here may not apply to all students and all department. It is meant to give students a general idea and ANKUR cannot be held responsible in any event. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) Can I get a TA/RA position in my department? Getting a teaching assistantship is based on rules and funding of your department or program. You must contact your department directly for this. Or else, personally contact any of the students in the Department Contact List of the pitt_grad_ankur Yahoo! Group. Does Ankur provide temporary accommodation? Yes. We provide temporary accommodation for a maximum of one week. You will be accommodated at homes of the current graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh. You must take care of your food, travel and other personal expenses. During this time, you have to search for an apartment and move in as early as you can. Important - Please fill in the information in the appropriate database in the ‘Database’ section of the pitt_grad_ankur Yahoo! Group. How much does it cost for temporary accommodation? Temporary accommodation is free. You will be staying along with the current graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh. When is the best time to arrive at Pittsburgh? The best time is to arrive at Pittsburgh is one week before the international orientation. During the one week, you should hunt for a suitable apartment, meet with the department faculty or possibly even work out your TA/RA options with the faculty. I do not have a scholarship. Can I get an on-campus job? Yes. -

Was Macht Pittsburgh So Erfolgreich? – Faktoren Eines Gelungenen Strukturwandels

Ruhr - Universität Bochum Fakultät für Sozialwissenschaften Was macht Pittsburgh so erfolgreich? – Faktoren eines gelungenen Strukturwandels M.A. - Arbeit Vorgelegt von: Nick Woischneck Matrikel Nr.: 108012268726 Betreut durch: Prof. Dr. Britta Rehder (Erstgutachterin), Prof. Dr. Rolf G. Heinze (Zweitgutachter) Bochum, den 03.11.2015 Ich danke allen, die an der vorliegenden Arbeit mitgewirkt haben. Besonderer Dank gilt meine r Familie und meinen Freunde, die mich w ährend meines Studiums unterstützt haben. Das dieser Arbeit zu Gr unde liegende Forschungsprojekt wurde von der Rosa Luxemburg - Stiftung und dem University Center for Social and Urban Research gefördert. Nick Woischneck Inhalt 1 Einleitung ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 4 2. Begriffskunde Strukturwandel ................................ ................................ ......... 6 2.1 Region ................................ ................................ ................................ ............ 6 2.2 Regionaler Strukturwandel ................................ ................................ ............ 7 2.3 Strukturpolitik ................................ ................................ ................................ 9 2.4 Altindustrielle Zentren ................................ ................................ ................. 10 3 Theorie ................................ ................................ ................................ ............ 12 3.1.1 Okönomische vs. Raumbezogene -

Albright, Rebecca Gifford, "The Civil War Abercrombie, Gen

A Major Robert Stobo, rev., 48, 389-91 rev. of Point of Empire :Conflict at the Abbott, John Charles, 48, 118 Forks of the Ohio, 53, 387-88 Abbott, WilliamD., 53, 9 Albree, Joseph (1850), 49, 171 Abbott, W. L. (1888), 48, 4 Albright, Rebecca Gifford, "The Civil War Abercrombie, Gen. James, 44, 108 ;45, 297 ; Career of Andrew Gregg Cur tin, Governor 46, 23, 251; 50, 99 of Pennsylvania," 47, 323-41; 48, 19-42, Aber's Creek (1758), 46, 52, 53 151-73 Abingdon, Earl of, 53, 109-10 Alcoholic consumption (1792-1823), 46, 349 Abolition Alcoholics, 46, 355 letter, 51, 77-79 Alcuin, Warren Co., 49, 314-16 Academy of Science and Art (Pgh.), 48, 60 Alden, Frank E., 48, 9 "Account Book of General John Neville," ed. Alden and Harlow (1896), 48, 9 by James H.Moon, 52, 345-60 Aldrich, Capt. C. S. (1864), 47, 235, 342 Acheson, David, 45, 38 Alexander, Eugene (1861), 49, 48 Acheson, Thomas, 45, 38 Alexander, Mary (c.1825), 49, 102 Acheson family, 45, 38 Alexander Hutchinson and Company (1895), Acorn, ship (1896), 48, 48 48, 291 Adams, Ida Bright (Mrs. Marcellin C.) Alexandria, Va. church history, 48, 2 CivilWar, 44, 107, 127; 45, 162, 241, 242, "The Civil War Letters of James Rush 244, 246, 250, 252; 46, 4, 11, 12, 14, Holmes," 44, 105-27 15, 270 Adams, John Quincy, 44, 238, 239; 47, 292 colonial, 44, 384, 392 Adams, Michael (1801), 49, 53 Alger, Horatio, 51, 287-88 Adams, Mrs. S. Jarvis, 44, 106 Aliquippa Incline Plane Company (1891), Adams, Sarah Jane, 44, 105-27 46, 328 Adams, Thomas, 46, 162 Allanowissica (1775), 47, 145, 152n Adams and Yernon, 48, 191 Allegheny Arsenal Additions to HSWP Collections. -

The Western Historical

The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine INDEX Volume 52 /.: *v Published quarterly by THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA 4338 Bigelow Boulevard, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania A Andrews, J. Cutler, rev. of Curry's Blueprint "Account Book of General John Neville," for Modern America, NonNan MilitaryLegis- edited by James H. Moon, with appendix lation of the First Civil War Congress, of letters, pages from account books, maps 199-201 of Reserve Tracts, etc., 345-360 Anti-Mormon feeling, high during investiga- "Account Book of General John Neville," tion of Reed Smoot and Mormon Church, photographic copy of, in Pennsylvania Di- 49; tosome, itwas persecution, 49 vision of Carnegie Library, Pittsburgh; Anti-Mormon petitions, about four million, original in vault storage, 354; appendix, sent to Senators Knox and Penrose from 355-360 Pennsylvania, 50; Knox, four others voted Hall, for Smoot, 50; failure to gain quick ap- "Address at the Dedication of Town proval Senate, 50; after Ligonier, Pennsylvania," June 13, 1969, from entire sum- by Stanton Belfour, 311-314 mer break, Congress to settle almost four- ) year-old case, 51 Agricultural sports in Pittsburgh, 67 Appleton Brothers, letters to Mathiot about Allegheny Conference on Community De- their losses on tunnel excavation on velopment, guiding organization for Point Portage Railroad, 158 Park project, 266; studied by other coun- Arensberg, Charles Covert, "The Spelling of tries, 266; established Point Park Com- Robert Neill Who Built the Neill Log mittee (1945) at request of Gov. -

Avian Rhetoric, Murmurations by Melissa T. Yang Bachelor of Arts, Mount Holyoke College, 2011 Master of Arts, University of Pitt

Avian Rhetoric, Murmurations by Melissa T. Yang Bachelor of Arts, Mount Holyoke College, 2011 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Melissa T. Yang It was defended on June 14, 2019 and approved by Troy Boone, Associate Professor, Department of English Peter Trachtenberg, Associate Professor, Department of English John Walsh, Associate Professor, Department of French & Italian Languages & Literatures Dissertation Co-Advisors: Cory Holding, Assistant Professor, Department of English Annette Vee, Associate Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Melissa T. Yang 2019 iii Avian Rhetoric, Murmurations Melissa T. Yang, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 This dissertation explores the omnipresent role birds play in the English language and in Western cultural history. Reading and weaving across academic discourse, multi-genre literature, and obsolete and everyday figures, I examine the multiplicity of ways in which birds manifest and are embedded in modes and materialities of human composing and communicating. To apply Anne Lamott’s popular advice of writing “bird by bird” literally/liberally, each chapter shares stories of a species, family, or flock of birds. Believing in the enduring rhetorical power of narrative assemblages over explicit thetic arguments, I’ve modeled this project on the movements of flocked birds. I initially proposed and now offer a prosed assembly of avian figures following each other in flight, swerving fluidly across broad and varied landscapes while maintaining elastic, organic connections.