University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intern Class 2021-2022

INTERN CLASS 2021- 2022 Saher Ali Halei Benefield Anna Bitners Kyla Cordrey M.D., M.S. M.D., Ph.D. M.D. M.D. Hometown: New Smyrna Beach, FL Hometown: Latham, MD Medical School: University of North Carolina - Hometown: Seattle, WA Hometown: Summit, NJ Medical School: Penn State Chapel Hill Medical School: Albert Einstein Medical School: Johns Hopkins For Fun I: run, hike, read (mostly fiction and For Fun I: Gardening/taking journalism), bake, and sample the Baltimore food For Fun I: cook with my For Fun I: cook, run along the care of my fruit trees, cooking, scene with my husband significant other, explore the harbor, and play/coach field volleyball and tennis, taking naps Why did you choose Hopkins? Two of my favorite outdoors nearby (hiking, kayaking, hockey. mentors from medical school were Harriet Lane (especially in my hammock!) alums, so I knew firsthand the caliber of pediatrician etc.), and try out new restaurants. Why did you choose Why did I choose Hopkins: Hopkins produces. I loved how intentional the Why did you choose Hopkins: Hopkins? Combined pediatrics- program is about educating its residents, and training The incredible people, patient The emphasis on education and residents to be educators. I was excited by the anesthesiology program, friendly graduated autonomy throughout training, variety of population, focus on education, teaching. I loved the culture of the and down-to-earth people, being electives, and ample opportunities to develop career impressive history, clinical pediatric program here as a close to my family, and the interests outside of clinical medicine. What really exposure, and supportive medical student, and I wanted to sealed the deal, though, were the stellar interactions I opportunities to make advocacy had on interview day! The PDs, residents, and staff leadership! be part of a program that and service part of my training were all exceptionally warm and kind and I knew I was What excites you most about appreciated its residents and What excites me most joining a family and not just a training program. -

The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Chapter One The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family The 1980–1985 Seasons ♦◊♦ As over forty-four thousand Pirates fans headed to Three Rivers Sta- dium for the home opener of the 1980 season, they had every reason to feel optimistic about the Pirates and Pittsburgh sports in general. In the 1970s, their Pirates had captured six divisional titles, two National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Their Steelers, after decades of futility, had won four Super Bowls in the 1970s, while the University of Pittsburgh Panthers led by Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett added to the excitement by winning a collegiate national championship in football. There was no reason for Pittsburgh sports fans to doubt that the 1980s would bring even more titles to the City of Champions. After the “We Are Family” Pirates, led by Willie Stargell, won the 1979 World Series, the ballclub’s goals for 1980 were “Two in a Row and Two Million Fans.”1 If the Pirates repeated as World Series champions, it would mark the first time that a Pirates team had accomplished that feat in franchise history. If two million fans came out to Three Rivers Stadium to see the Pirates win back-to-back World Series titles, it would 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. break the attendance record of 1,705,828, set at Forbes Field during the improbable championship season of 1960. The offseason after the 1979 World Series victory was a whirlwind of awards and honors, highlighted by World Series Most Valuable Player (MVP) Willie Stargell and Super Bowl MVP Terry Bradshaw of the Steelers appearing on the cover of the December 24, 1979, Sports Illustrated as corecipients of the magazine’s Sportsman of the Year Award. -

The Boston Park League, by John Hinds

The Boston Park League bvlohnHinds Hall fter 65 years of continuous existence,the Although official records are not kept, the Baseball oldest Boston Park League has been many things of Fame recognizesthat the Boston Park League is the to many people. The one thing that it amateurleague in continuous existencein baseball. who remains for all those who have played and This rich history is acknowledged in the players for the presentplayers, is familY. have gone on to play in the major leagues' They include the Organized by the City of Boston Mike Fornieles who played for the Supreme Saints and and the Department of Parks and Recreation, the Red Sox; Vito Tamulis, the St. Augustine team the I-eaguewas established to give top high Yankees; Johnny Broaca, the Yankees; Tom Earley, Casey Club and the Red school, college and older players the opportunity to hone Boston Braves; Joe Mulligan, the Bob Giggie, the their skills. Sox; Joe Callahan, the Boston Braves; team and the League play starts the third week in May and continues Boston Braves; Curt Fullerton, the Charlestown to the end of July. Playoffs follow regular seasoncompeti- Boston Braves. League and the majors tion. In a unique format, the top four teams make the play- Catchers who played in the and the McCormack offs. The last-place team drops to the Yawkey League, and include Pete Varney, the White Sox Paul team and the White the winner of the Yawkey Division replaces the last-place Club; George Yankowski, the St. and the Cleveland team in the Senior Park League. -

Healthy Housing Strategy

HEALTHY CITY STRATEGY Healthy Housing Strategy Healthy Housing Strategy kelowna.ca 2 Helathy Housing Strategy Acknowledgements The development of the Healthy Housing Strategy was led by City of Kelowna’s Policy & Planning Department and was Healthy City Strategy Steering Committee supported by City staff, Interior Health and numerous other community organizations. The City of Kelowna would like to acknowledge the following members of the Healthy City Strategy Steering Committee and the Healthy Housing Stakeholder Advisory Committee for their contributions to this project: The City of Kelowna would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the following: • Community stakeholders that participated in the Stakeholder Workshops including: Adaptable Living, BC Housing, Canadian Home Builders Association, City of Kelowna Interior Health Canadian Mental Health Association, Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Central Okanagan Early Years • Doug Gilchrist • Dr. Sue Pollock Partnership, Central Okanagan Foundation, Community • Danielle Noble-Brandt • Heather Deegan Living BC, Evangel Housing Society, FortisBC, Habitat for • Michelle Kam • Deborah Preston Humanity, High Street Ventures, Honomobo, Interior Health, Kelowna Intentional Communities, KNEW Realty, Landlord BC, Mama’s for Mama’s, Okanagan Boys & Girls Healthy Housing Stakeholder Club, Okanagan College, Pathways Abilities Society, Advisory Committee: People in Motion, Regional District of the Central Okanagan, Seniors Outreach and Resource Centre, Society of Hope, • Danna Locke, -

Design Considerations for Retractable-Roof Stadia

Design Considerations for Retractable-roof Stadia by Andrew H. Frazer S.B. Civil Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of AASSACHUSETTS INSTiTUTE MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN OF TECHNOLOGY CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING MAY 3 12005 AT THE LIBRARIES MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2005 © 2005 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved Signature of Author:.................. ............... .......... Department of Civil Environmental Engineering May 20, 2005 C ertified by:................... ................................................ Jerome J. Connor Professor, Dep tnt of CZvil and Environment Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:................................................... Andrew J. Whittle Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies BARKER Design Considerations for Retractable-roof Stadia by Andrew H. Frazer Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 20, 2005 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT As existing open-air or fully enclosed stadia are reaching their life expectancies, cities are choosing to replace them with structures with moving roofs. This kind of facility provides protection from weather for spectators, a natural grass playing surface for players, and new sources of revenue for owners. The first retractable-roof stadium in North America, the Rogers Centre, has hosted numerous successful events but cost the city of Toronto over CA$500 million. Today, there are five retractable-roof stadia in use in America. Each has very different structural features designed to accommodate the conditions under which they are placed, and their individual costs reflect the sophistication of these features. -

NCAA Tourney Notes Stanford.Indd

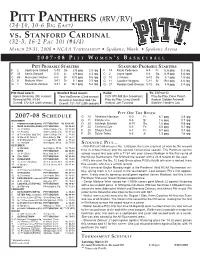

(#RV/RV) PITT PANTHERS (24-10, 10-6 BIG EAST) VS. STANFORD CARDINAL (32-3, 16-2 PAC 10) (#4/4) MARCH 29-31, 2008 • NCAA TOURNAMENT • Spokane, Wash. • Spokane Arena 22007-080 0 7 - 0 8 P IITTT T W OOMENM E N ’ S B AASKETBALLS K E T B A L L PITT PROBABLE STARTERS STANFORD PROBABLE STARTERS F 2 Sophronia Sallard 5-10 So. 2.9 ppg 2.5 rpg F 14 Kayla Pedersen 6-4 Fr. 12.6 ppg 8.3 rpg F 33 Xenia Stewart 6-0 Jr. 8.9 ppg 4.3 rpg C 2 Jayne Appel 6-4 So. 14.9 ppg 8.8 rpg C 45 Marcedes Walker 6-3 Sr. 13.9 ppg 9.6 rpg G 10 JJ Hones 5-10 So. 6.1 ppg 1.9 rpg G 0 Mallorie Winn 5-11 Sr. 8.1 ppg 3.5 rpg G 11 Candice Wiggins 5-11 Sr. 19.8 ppg 4.6 rpg G 1 Shavonte Zellous 5-11 Jr. 18.1 ppg 5.4 rpg G 21 Rosalyn Gold-Onwude 5-10 So. 4.9 ppg 2.4 rpg Pitt Head Coach: Stanford Head Coach: Radio: TV: ESPN2HD Agnus Berenato (5th season) Tara VanDerveer (22nd season) FOX 970 AM (live broadcast) Play-by-Play: Dave Pasch Record at Pitt: 89-64 Record at Stanford: 569-136 Play-by-Play: Greg Linnelli Analyst: Debbie Antonelli Overall: 372-328 (24th season) Overall: 721-187 (29th season) Analyst: Jen Tuscano Sideline: Heather Cox PITT OFF THE BENCH 2007-08 SCHEDULE G 10 Taneisha Harrison 6-0 Fr. -

Learning Cities As Healthy Green Cities: Building Sustainable Opportunity Cities Peter Kearns PASCAL International Exchanges

Australian Journal of Adult Learning Volume 52, Number 2, July 2012 Learning cities as healthy green cities: Building sustainable opportunity cities Peter Kearns PASCAL International Exchanges This paper discusses a new generation of learning cities we have called EcCoWell cities (Economy, Community, Well-being). The paper was prepared for the PASCAL International Exchanges (PIE) and is based on international experiences with PIE and developments in some cities. The paper argues for more holistic and integrated development so that initiatives such as Learning Cities, Healthy Cities and Green Cities are more connected with value- added outcomes. This is particularly important with the surge of international interest in environment and Green City development so that the need exists to redefine what lifelong learning and learning city strategies can contribute. The paper draws out the implications for adult education in the Australian context. We hope it will generate discussion. Learning cities as healthy green cities 369 Introduction The UN Rio+20 Summit held in June 2012 reminds us of the critical importance of addressing the great environmental issues to ensure the future of Planet Earth. At the same time, escalating urbanisation around the world points to the challenge of building cities that are just and inclusive, and where opportunities are available for all throughout life, and where the well-being of all is an aspiration that is actively addressed in city development. This challenge is widely recognised. The World Bank in its ECO2 Cities initiative has observed that ‘[u]rbanisation in developing countries is a defining feature of the 21st century’ (World Bank 2011). -

Anne Arundel County Corridor Growth Management Plan Final Report

FINAL REPORT Anne Arundel County Corridor Growth Management Plan July 20, 2012 LEGEND Baltimore City US 50 MD 2 South MD 2 North Howard County I-97 MD 32 MD 100 4.6-Miles MD 295 MD 3 MD 607-MD 173 14-Miles 2.5-Miles 16-Miles Benfield Blvd. 13-Miles MD176 14-Miles 17-Miles MD170 4.6-Miles MD 713 Ridge Rd. 11-Miles AACOBoundary Anne Arundel County 17-Miles 7-Miles 19-Miles 4-Miles Prince George's County Prepared by: µ 0 1 2 4 Miles a Joint Venture 7055 Samuel Morse Dr., Suite 100 | Columbia, MD 21406 | 410.741.3500 Corridor Growth Management Plan Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 CHAPTER 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................1-1 1.1 OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Purpose and Scope ................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.2 Project Costs .......................................................................................... 1-2 1.1.3 Alternatives Tested ............................................................................... 1-2 1.1.4 Priorities ................................................................................................ 1-4 1.1.5 Next Steps ............................................................................................. 1-4 1.2 US 50 .................................................................................................................. 1-4 1.3 MD 2 - NORTH ................................................................................................... -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

St. Louis Regional Chamber Records (S0162)

PRELIMINARY INVENTORY S0162 (SA0016, SA2507, SA2508, SA2799, SA2958, SA3101, SA4087, SA4105, SA4127) ST. LOUIS REGIONAL CHAMBER RECORDS This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center- St. Louis. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Introduction Approximately 45 cubic feet, 2088 photographs, 174 videos, 7 cassette tapes The St. Louis Regional Chamber records contain materials from its six-predecessor organizations, the City Plan Commission, the Metropolitan Plan Association, the St. Louis Research Council, the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce, the Regional Industrial Development Corporation (RIDC), and the St. Louis Regional Commerce and Growth Association (RCGA). The records include correspondence, meeting minutes, reports, photographs, newspaper clippings, and videotapes, documenting the St. Louis Regional Chamber and its predecessor’s mission to promote regional cooperation and planning for the development of the area’s resources. Materials of interest include RCGA and RIDC’s reports and studies, which provided economic and sociological analyses, as well as statistical data, of urban problems in transportation, public works, labor, the environment, capital investment, manufacturing, industrial education, and employment. The materials in this collection are incomplete, as they do not contain the records of the City Plan Commission before 1912. Donor Information The records were donated to the University of Missouri by R.A. Murray on February 23, 1971 (Accession No. SA0016). An addition was made on January 17, 1983 by James O’Flynn (Accession No. SA2507). An addition was made on February 16, 1983 by James O’Flynn (Accession No. SA2508). An addition was made on June 24, 1987 by Bill Julius (Accession No. -

Ford Bids N.J. GOP Put Aside Differences

The Daily Register VOtf.98 NO.70 SHREWSBURY, N. J. MONDAY, OCTOBER 6, 1975 • 15 CENTS Byrne: Ford is ^terrorizing9 state residents "MlBy JOHN T . MetiOKAN Saturday. The state has one dictions are not the only op- of the natural gas consumed nor© said , "I think that's what being held off the market by gas crisis. Byrn..e said Con. - of the highest unemployment tions open to the federal gov- in New Jersey is used by he is trying to do " producers in hopes of getting gress has a plan similar to his TRENTON (AP) - Oov rates in the nation. ernment. homeowners and said it was Byrne said the President's a bigger price if price con- own for reallocation which he Brendan T. Byrne his ac- The President said more He repeated his recommen- not fair "to sock these own words indicate that there trols are lifted. thinks will be put into effect cused President Ford of "ter- South Jersey industrial plants dation that Ford allow reallo- people" with higher prices. is extra natural gas which The governor said the Pres- in time to help the employ- rorizing" New Jersey resi- might have to close this win- cation of existing natural gas could be obtained for New ident could not have meant ment situation in New Jersey Offstage, Byrne was asked dents by threatening more ter if a predicted 52 per cent supplies to increase the sup- Jersey and other states in that deregulation would some- ihis year. unemployment for their state cutback in natural gas sup- ply in the Northeast. -

Healthy Communities Practice Guide

CANADIAN INSTITUTE OF PLANNERS Healthy Communities Practice Guide This project has been made possible through financial and in-kind contributions from Health Canada, through the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer’s CLASP initiative, as well as the Heart and Stroke Foundation and the Canadian Institute of Planners. The views expressed in this guide represent the views of the Canadian Institute of Planners and do not necessarily represent the views of the project funder. AUTHORS PROJECT FUNDERS CLASP COALITIONS LINKING ACTION & SCIENCE FOR PREVENTION An iniave of: HEALTHY COMMUNITIES PRACTICE GUIDE / II Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................1 2. Framework ........................................................................................................4 3. Collaboration in Practice ..................................................................................10 4. Innovations in Land Use Planning and Design ....................................................14 4.1. Creating Visions, Setting Goals, and Making Plans ..........................................................14 4.1.1. Engagement, Participation and Communication .............................................................. 15 4.1.2. Community Plans ........................................................................................................... 18 4.1.3. Functional Plans: Active Transportation, Open Space, Food Systems .............................. 23 4.2.