Why-Dont-We-Do-It-On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Greder Workshop Overview

T O M G R E D E R 2020 Finding Comedy: Theatre, Play, contemporary clown OSKAR Tom Greder. Obergasse 21, CH-2502 Biel. +41-32 322 5562. [email protected] and creativity workshops Contents: Page: Workshop Introduction 1 Pedagogy 2 - 3 Content 3 Summary graphic 4 Key Vocabulary 5 Teaching History 6 Testimonial 1 7 Testimonial 2 8 Additional Testimonials 9 School Workshop Testimonials 10 Tom Greder tomoskar.com | kinopan.com [email protected] +41 (0)788 911 965 Workshop introduction In addition to 31 years experience as a circus, cabaret, street and theatre performing artist, Tom Greder directs and conducts regular creativity, performing, communication and team-building workshops throughout the world. Based on 'Play' as being the fundamental expression of human creativity and the basis of meaningful interaction and problem solving, the workshops encourage a personally relevant and transformative expression for all those who want or need it. Toms' distinct approach focuses on the relationship between the 'Person', 'Character' and 'Artist' in all of us. By understanding, exploring and harmonising the often conflicting nature of these “inner voices”, participants gain a clearer awareness of themselves, their talents and their creative process. The inspiring and challenging workshops are aimed at anyone who wishes to gain a deeper insight into their creativity and abilities, and develop an empowered and liberated stage presence. 1 OSKAR Tom Greder. Obergasse 21, CH-2502 Biel. +41-32 322 5562. [email protected] Workshop Pedagogy In order to create articulate and engaging communication or poignant performance, a deeper level of understanding about the human condition has to be awakened. -

Igor Mamlenkov Borisov

Igor Mamlenkov Borisov domovoi.ch © by Anna Salagaeva Information Acting age 25 - 39 years Nationality Spanish, Russian Year of birth 1988 (33 years) Languages Danish: basic Height (cm) 179 German: basic Weight (in kg) 72 English: fluent Eye color brown Russian: native-language Hair color Black Spanish: fluent Hair length Balding French: basic Stature normal Italian: fluent Place of residence Switzerland Dialects Standard German: only when Housing options Berlin, Barcelona, Paris, required Zurich, Moscow, Indian-English: only when Geneve, Lausanne, required Vienna, Bern, Basel, Argentine Spanisch: always Dresden, Copenhagen, Accents Indian: only when required London, Warsaw, Rome, English: only when required Venice, Milan Russian: only when required Spanish: only when required Instruments Djembe: basic Ukulele: basic Balalaika: basic Sport Pilates, Qigong, Yoga Dance Butoh: basic Robot: basic Standard: medium Mime: professional Break dancing: basic Performance: professional Choreography: medium Expressionist dance: medium Motion dance: medium Improvisation dance: professional Experimental dance: medium Contact Improvisation: medium Contemporary dance: medium Profession Actor, Cabaret artist, Comedian, Dancer, Dubbing actor, Vita Igor Mamlenkov Borisov by www.castupload.com — As of: 2021-07-23 Page 1 of 5 Puppeteer Pitch Baritone Primary professional training 2019 Accademia Teatro Dimitri Other Education & Training 2019 Puppet Manipulation Workshop by DUDA PAIVA COMPANY 2016 Physical Theatre Summer Project LOD/ BOAT Creating and performing -

Interview Ira Seidenstein

Interview with Ira Seidenstein (IS) by Mike Finch (MF), on behalf of Circus Network Australia Introduction MF- Ira Seidenstein is a highly respected, skilled and experienced clown, performer, acrobat, teacher, mentor and elder. He is originally from Pittsburgh USA, but for many years has been based in Australia. Ira has worked all around the world alongside a virtual Who’s Who of physical, clown and Circus performance from major international luminaries and iconic organisations, to grassroots practitioners and soloists. We are lucky enough to have access to him for this interview about his life, his influences, his methodology, some advice and his hopes for the future. In his own words, “Intuition isn’t only knowing what to do next. It is also not knowing what else to do and having no choice”. MF- Hi Ira, thanks so much for your time. Firstly I want to thank you for offering yourself up to be interviewed. We intend this to be the inaugural interview of a series for Circus Network Australia on Australian Circus people, and I’m glad you will be the first! Let’s start at the beginning. Can you tell us what your childhood was like? IS- Oy vey Maria! It was located in the melting pot of the USA. Pittsburgh is a city with three rivers the Allegheny and Monongahela join to form the Ohio which helps form the Mississippi. There are lots of hills of the Allegheny/Appalachian Mountains. Pittsburgh is surrounded by farms and coal towns populated by ethnic Europeans who were starving in the 1800s. -

Le Guide Des Transferts B

LeMonde Job: WMR3497--0001-0 WAS TMR3497-1 Op.: XX Rev.: 23-08-97 T.: 08:42 S.: 75,06-Cmp.:23,09, Base : LMQPAG 53Fap:99 No:0045 Lcp: 196 CMYK b TELEVISION a RADIO H MULTIMEDIA CINÉMA FRANCE-CULTURE Des centaines « Stavisky... » « L’Histoire La légende immédiate » : de solutions d’un escroc portraits de gens de jeux hors du commun de maisons. Page 29 filmée par Alain Resnais. Page 22 à télécharger. Page 28 b b b b b TF1 FR 2 Le guide des transferts b b b FR 3 bbbbb Canal + Chambardement dans toutes les grandes chaînes. Signe des temps, cette fois il a pour théâtre le secteur de Portraits l’information, ce qui situe les enjeux de l’année qui vient. d’internautes Guillaume Durand, Patrick de Carolis, Albert du Roy, Michel Field, Paul Amar, d’autres encore, changent remarquables (5) de chaîne comme de club de football. Petit guide pour La princesse Liz crée son royaume s’y retrouver. Pages2à5 sur Internet. Pages 26 et27 SEMAINE DU 25 AU 31 AOÛT 1997 LeMonde Job: WMR3497--0002-0 WAS TMR3497-2 Op.: XX Rev.: 23-08-97 T.: 08:42 S.: 75,06-Cmp.:23,09, Base : LMQPAG 53Fap:99 No:0010 Lcp: 196 CMYK RENTRÉE LE GUIDE DES TRANSFERTS La valse des stars de l’information tissement reprennent elles aussi leur ser- rédaction mécontente de sa hiérarchie et Qui aurait pensé, à la rentrée 1996, vice sur leur chaîne, à quelques « débar- pressée d’entreprendre une réforme pro- marquée par les retombées qués » près dans un désintérêt quasi fonde du JT. -

77 Ff Intro.Pdf

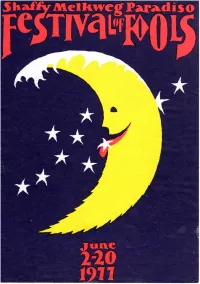

SOME FOOLS nederland CAROUSSEL ITALIC FIGURE NTH EATER TRIANGEL LEOPOLDO MASTELLONI DOGTROEP BAMSISTERS ZWITSERLAND ONA FHANKE LIJK TONEEL MICHAEL DROBNY PIGEON DROP PERZIG DUO TRIPLEX SUSHA & BAND NEEF DIEDERIK BERRY NOOY SIERRA LEONE HANS DULFER & de PERIKELS MUYEI POWER N-ZEELAND engeland GEOFF CAVANDER BAND THEATRE SLAPSTIQUE POO TS BA R N TH E A TR E SALAKTA BALLOON BAND ACTION SPACE ABAKADABRA JOHN MELVILLE & KABOODLE NO LA RAE 2 m 20 \w\ JUSTIN CASE COLIN BARRON ANNIE STAINER BOB KERR'S WHOOPEE BAND DEAFSCHOOL JOHNNY RONIX) TRIO ¥ mw\i HLOL coxiIILL COLIN SCOT usa FRIENDS ROADSHOW OF mm SALT LAKE MIME COMPANY LOS ANGELOS MASK THEATRE SAN FRANCISCO MIME TROUPE doornroosje SPIDER WOMAN TUMBLE WEED Verl. Groenstr. 22 - NIJMEGEN ZUPE & OTTO tel. 080-55 98 87 \ms\kweg STEVE HENSEN Alleen van do 2 t/m zo 12 RIVER Li]nbaansgracht 234 a (steeds do, vr, za, zo) CHRIS TORCH tel. 24 17 77 FRIENDS BIG BAND aanvang: do v.a. 20.00 uur ARCHIE SHEPP wo t/m zo aanvang 20. 30 uur - vr, za, zov.a. 21.00 uur EXPRESSION shafty thoogt frankrijk Keizersgracht 324 Hoogt 4 -UTRECHT tel. 23 13 11 tel. 030-31 22 16 THEATRE DU MATIN COMPAGNIE DU POT AUX do t/m zo aanvang 20.30 uur alleen op ma 6, di 7, wo 8 juni ROSES aanvang 20.30 uur ARC HE DE NOE PHILIPPE DUVAL Weteringschans 6-8 KASSA OPEN: FRANK & GOA tel. 16 45 21 MELKWEG: IS.00 uur wo t/m za aanvang 20. 30 uur argcntinic geen voorverkoop SHAFFY: wo t/m zo v.a. -

Ezra Lebank and David Bridel, These Legends of Comedy Reveal the Origins, Inspirations, Techniques, and Philosophies That Underpin Their Remarkable Odysseys

Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:32 09 August 2016 Clowns Clowns: In Conversation with Modern Masters is a groundbreaking collection of conversations with 20 of the greatest clowns on earth. In discussion with clown aficionados Ezra LeBank and David Bridel, these legends of comedy reveal the origins, inspirations, techniques, and philosophies that underpin their remarkable odysseys. Featuring incomparable artists, including Slava Polunin, Bill Irwin, David Shiner, Oleg Popov, Dimitri, Nola Rae, and many more, Clowns is a unique and definitive study on the art of clowning. In Clowns, these 20 master artists speak candidly about their first encounters with clowning and circus, the crucial decisions that carved out the foundations of their style, and the role of teachers and mentors who shaped their development. Follow the twists and turns that changed the direction of their art and careers, explore the role of failure and originality in their lives and performances, and examine the development and evolution of the signature routines that became each clown’s trademark. The discussions culminate in meditations on the role of clowning in the modern world, as these great practitioners share their perspectives on the mysterious, elusive art of the clown. Ezra LeBank is the Head of Movement for the Department of Theatre Arts at California State University, Long Beach. He has published articles in the Journal for Laban Movement Studies and Total Theatre Magazine. He performs and teaches across North America and Europe. Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:32 09 August 2016 David Bridel is the Artistic Director of The Clown School in Los Angeles and the Director of the MFA in Acting in the School of Dramatic Arts at the Uni- versity of Southern California. -

Tom Greder Biography

T O M G R E D E R Theatre performer & director Workshop facilitator Corporate coach Arts & culture advocate P E R F O R M A N C E : W O R K S H O P S : C O R P O R A T E : Overview 1 Introduction 8 Introduction 15 Performances 2-4 Pedagogy 9 Climate 16 Press Quotes 4 Content 9 Work History 16 Awards 5 Overview 10 Testimonial 16-17 Formation & Studies 5 Vocabulary 11 Press Report 18 Companies 5 Teaching History 11-12 Participant Feedback 18 Press Quotes 6 Testimonials 12-14 Performing History 6-7 Links & Contact 18 Directing History 7 T O M O S K A R - P E R F O R M A N C E O V E R V I E W - From full-length theatre to cabaret sketches, circus turns contemporary circus, theatre and street productions, and street performances, Tom Greder, alias Oskar, festivals, films, corporate events, workshops, team- captivates his audience leading them to a world building and promotional projects throughout the world. where life and comedy become one. Since 1988, he has produced and toured eight Developed over 31 years as a solo act, in group full-length productions and numerous circus and circus and theatre companies or in the multi-award cabaret routines internationally, as well as conducting winning clown duo “Oskar & Strudel”, his unique creativity, physical theatre and contemporary interactive comedy style and range of physical skills clowning workshops throughout the world. and characters allow him to adapt to any audience, anywhere. -

Jango Edwards 10 FOOLS FESTIVAL PROGRAMME 12

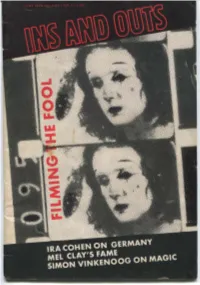

m~~ &~[ID ®lliJ~ A Magazine OfAwareness This magazine happened when a bunch of the good guys got toyether. -t :r: Starborn earthlings whose vision of the present moment often extends m beyond the confines of commonplace terrestrial awareness, the good m guys must not be confused with those virgin cowboys who sip unspiked o lemonade throughout every last remake of a Tom Mix film . Neither are -t they pubescent Gotteskinder masturbating Christian images in Dam o Square on Sunday afternoons or evangelical outcasts from the Sally :0 Army. Though occasionally celibate, especially when levitating from en straw mats i n a backjungle Bihari village or sharing cheese omelettes Publisher Salah Harharah :r:" with Noah and his motley crew atop Mount Ararat, they are by and :0 large a rather horny lot, the women as well as the men. Some of us even m Editor Edward Woods 2 give pretty good head... or so I've been told after coming up for a breath C of unmuffled air. Copy Editor Jane Harvey S In another sense, however, we do somewhat resemble (if only at a dis· tance) a kind of inter-9alactic cavalry trumpeting its arrival with poems Art Directors Peter Vermeulen in place of bugle notes, slinging cameras and pens where others might Marijke Mooy wear scabbards and generally creating a publ ic disturbance amid the hos· tile disorder of philistine tranquillity. Accused, as always, of preaching but to the converted, we in fact do not preach at all - and will happily Staff Artist Mark Leggo accept a cream pie from any Groucho Marxist who catches one of us do· ing so. -

Kiki Bio and Cv.Pages

Francisco Vita Roldan (KiKi) Francisco fell into his first job as a children's party clown in 1995 unaware that this first gig would be the beginning of a lifetime journey through clown, comedy and circus. Since, he has studied in over five countries and performed in over 20 throughout Europe, The Middle East, Asia, Canada and Australia, independently and with companies. He is an accomplished traditional juggler learning from Antonio Benitez, The Rogelio Rivelo School and Raul Fernandez Sala Pirueta and performing in Juggling Conventions alongside legends such as Matt Hall and Ivan Pecell. Although now his style is dedicated to a more contemporary form of object manipulation and contact juggling - bringing everyday objects (tables, suitcases, umbrellas) to life and incorporating them in his juggling routines. Francisco has completed intensive studies of clown in the Phillipe Gaulier School in Paris and with Eric De Bont at Bont's International Clown School in Ibiza. He has also done workshops with many other clown and comedy teachers including Loco Brusca, Aitor Bassuri, Gabriele Chame and has undergone one on one character development direction with Ira Stiedenstein and Jango Edwards. Francisco is has been continually touring the world for the past 8 year with his solo street show ‘The TNT Show’ and his duo with his wife ‘Las Cossas Nostra - the show’ and have appeared at major festivals and events around the world. In 2016 he presented an indoor theatre show ‘Grumpy Pants’ at the Adeladie Fringe Festival with RCC and was invited for a return -

Bio Jan Dillen

Bio Jan Dillen As a cliniclown-oldtimer my passion is to guide you into clowning, from starters to advanced level, over workshops and coaching. Education Way back in time Bachelor Social Cultural Work in Belgium (1983-1985). Drama teacher Lod. De Raet and DACEB (1985-1987). Creative Thinking at University Antwerp (1994). Education in Belgium and other countries about artistic development and body work: Mime School in Antwerp (Belgium) and Amsterdam (Holland) ClownSchool in Paris (Compagnie Du Moment). Ongoing Clown Trainings with Carina Bonan, Serge Ponselet, Els Jansen, Avner Eisenberg, Moshe Cohen, Jango Edwards, Michael Christensen (American Founder of the Hospital Clowns) and others. Recent ClownSchool International, clown and dementia Online 8 week class with Angie Foster and Vivian Gladwell from Nose to Nose England. (2020 - 2021) Jobs Social Cultural Worker in different organisations for youth and employment. Worked with Dan Frood and Victoria Marks, movement project ‘The Beweging Antwerpen’, Fura Dels Baus Spain and Enrique Vargas, Colombia, Théatre de los Sentidos. Clown in hospitals, institutions and psychiatry for children from 1999 till 2019. Artistic Director of Cliniclowns Belgium from 2005 till 2009. Trainer of hospitalclowns worldwide for Theodora Foundation, Rote Naze, Cliniclowns Holland, Cliniclowns Belgium, Dr. Clown Malta. Leading advanced training for hospitalclowns in Belgium, Suisse, France, England, Spain, Italy, White-Russia,Turkey, Hong-Kong China, Malta and Austria. Co-founder of the school ‘Clownsense’, Belgium since 2014: ● Basic and advanced training for clowns in the field of care ● Organising weekly play-dates for clowns in a ‘Labo’ ● Thematic workshops around music and clowning Clown Teacher for Hiketnunk vzw ● Online ClownClass ● Mentoring the clowns-spirit ● Coaching duo-clowns and artistic projects Extra Advising ‘Zorgclowns and Co’ Belgium ‘Dance and Clown’ with Sue Rickards and Geert Meeus 2020: published my first book ‘Clownslogica’. -

Tickets From£5

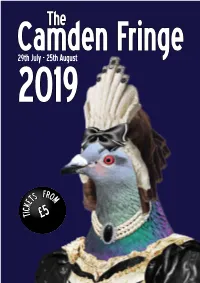

Camden The Fringe 201929th July - 25th August S FROM ET K C I T £5 29th July - 25th August The Camden Fringe 2019 WELCOME TO THE CAMDEN FRINGE 2019 Etcetera Theatre This is the 14th Camden Beating that long service record Paul Putner’s Embarrassment - are the Plews family at Upstairs at Me And Madness (The Band) 29 July 2.30pm Fringe. It’s the ruby anniversary of Madness and Paul Putner celebrates the the Gatehouse. They’ve been atop past 40 years as a lifelong fan. A story of a young, obsessive, nutty boy £6.00 (concs £5.00) We can’t quite believe we’ve been who took his passion for the legendary band just one step beyond! Enjoy spoken word Highgate Hill for 21 years and we heartfelt and honest tales of freaky fandom, demented dancing, dodgy going for so long, but there it is. Over have loved having them as part of the haircuts, glorious gigs and some encounters with Madness themselves. the 14 years we’ve been working on Camden Fringe since 2010. the Fringe there have been lots of changes: to our lives, to Camden One of the new spaces for 2019 is The S.o.S Theatre Company Phoenix Artist Club itself and to the festival. We’ve seen Chapel Playhouse in Kings Cross, 365 29-31 July 8.30pm thousands of shows, performers and which opened its doors in January. It’s 2017, New Year’s Eve. Josh Parker, a young lad with a good heart, was appointed the role of ‘2017’. -

Jango Edwards E Um Corpo Cômico Transgressor André Luiz Rodrigues

Jango Edwards e um Corpo Cômico Transgressor André Luiz Rodrigues Ferreira* * André Rodrigues é performer, ator e professor. Doutor e Mestre em Artes Cênicas pelo PPGAC/UNIRIO, investiga o diálogo entre arte da performance, grotesco e bufonaria. Website: https://andrerodriguesart.wordpress.com/>. 70 Rebento, São Paulo, n. 8, p. 70-93, junho 2018 Resumo | Este trabalho tem por objetivo realizar a investigação da corporeidade do palhaço como elemento fundamental de expressividade e potência cênica. O artigo tem como base de estudo a análise de obra a partir da observação de um número de palhaço criado e executado pelo palhaço norte- americano Jango Edwards, no espetáculo The Bust of Jango. Artista cômico multifacetado, Edwards coloca em jogo em suas atuações algumas questões importantes sobre a comicidade clownesca, como o grotesco, a transgressão e o embaralhamento entre as fronteiras da arte e da vida. Adquirindo um caráter ridículo e ampliado, a corporeidade do palhaço abre linhas de fuga para ações e visões de mundo capazes de possibilitar, ao intérprete cênico e ao espectador, novas apreensões das relações entre corpo, pensamento e espacialidade. Palavras-chave: Palhaço. Corporeidade. Grotesco. 71 Rebento, São Paulo, n. 8, p. 70-93, junho 2018 Palhaço e inadequação A tipologia cômica do palHaço acompanHa, de forma multifacetada e não linear, a própria História da Humanidade, pois, transcendendo as especificidades de cada ordem social, Há na organização dos Homens o lugar daquilo ou daquele que é risível. Palhaços, bem como mendigos, ébrios e portadores de características excêntricas, são figuras que, por sua inadequação em relação à cHamada “normalidade”, transitam num âmbito marginal das sociedades, sendo, muitas vezes, alvo de cHacota e zombaria.