5E3e9d4991c96-1326784-Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications By Name: Syeda Batool National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 1 The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications by Name: Syeda Batool M.Phil Pakistan Studies, National University of Modern Languages, 2019 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY in PAKISTAN STUDIES To FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF PAKISTAN STUDIES National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 @Syeda Batool, April 2019 2 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THESIS/DISSERTATION AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Social Sciences for acceptance: Thesis/ Dissertation Title: The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications Submitted By: Syed Batool Registration #: 1095-Mphil/PS/F15 Name of Student Master of Philosophy in Pakistan Studies Degree Name in Full (e.g Master of Philosophy, Doctor of Philosophy) Degree Name in Full Pakistan Studies Name of Discipline Dr. Fazal Rabbi ______________________________ Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Prof. Dr. Shahid Siddiqui ______________________________ Signature of Dean (FSS) Name of Dean (FSS) Brig Muhammad Ibrahim ______________________________ Name of Director General Signature of -

Sherpi Kangri II, Southeast Ridge Pakistan, Karakoram, Saltoro Group

AAC Publications Sherpi Kangri II, Southeast Ridge Pakistan, Karakoram, Saltoro Group Sherpi Kangri II (ca 7,000m according to Eberhard Jurgalski and the Miyamori and Seyfferth maps; higher and lower heights also appear in print) lies at 35°28'45"N, 76°48'21"E on the Line of Control between the India- and Pakistan-controlled sectors of the East Karakoram. Prior to 2019, it had been attempted only once. In 1974, a Japanese expedition trying the east ridge of Sherpi Kangri I (7,380m) gave up and instead reported fixing around 1,000m of rope up the southeast ridge of Sherpi Kangri II, before retreating at 6,300m due to technical difficulty. On August 7, Matt Cornell, Jackson Marvel, and I (all USA) summited this peak via the southeast ridge in seven days round trip from base camp. Porter shortages resulted in a significantly lower base camp than we had planned—at around 3,700m on the west bank of the Sherpi Gang Glacier, more or less level with the first icefall. This required establishing three additional camps several kilometers apart, ferrying loads through complicated terrain, to reach the glacier plateau below the peak. After investing much time and energy on this approach, including portering some of our own loads to base camp, we did not have time to acclimatize as slowly as we would have liked for higher elevations. We therefore chose the seemingly nontechnical southeast ridge, so that we could bail quickly if one of us began to show signs of acute altitude sickness. We climbed to the summit from our highest glacier camp over two days, with one bivouac on the ridge. -

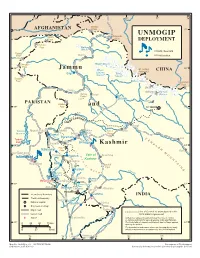

Download Deployment Map.Pdf

73o 74o 75o 76o 77o 78o Mintaka 37o AFGHANISTAN Pass 37o --- - UNMOGIP Darkot Khunjerab Pass Pass DEPLOYMENT - Thui- An Pass Batura- Glacier UN HQ / Rear HQ Chumar Khan- Baltit UN field station Pass Shandur- Hispar Glacier Pass 36o 36o Jammu Chogo Mt. Godwin CHINA Lungma Austin (K2) Gilgit Biafo 8611m Glacier Glacier Dadarili Baltoro Glacier Pass Karakoram Pass Sia La - Chilas Bilafond La Siachen Nanga Astor Glacier Parbat -- 8126m Skardu PAKISTAN Goma Babusar-- 35o Pass and 35o NJ 980420 X Kel ONTR C O F L LINE O - s a r Kargil D Tarbela Muzaffarabad- Tithwal- Wular Zoji La Dras- Reservoir Sopur Lake Pass Domel J h Jhe ---- e am Baramulla a m Z - Leh Tarbela A Dam Uri Srinagar- N Chakothi Kashmir S o o 34 K - 34 Haji-- Pir A - R Rawalakot Pass P - - - i- Karu Campbellpore Islamabad r M - O Titrinot P Vale of Anantnag Islamabad--- Poonch U a Kashmir N Mendhar n T Rawalpindi- Kotli j - A a- Banihal I ch l Pass N - n u R S P Rajouri C a n hen - Mangla g e ab Reservoir Naushahra- - Mangla Dam New Mirpur- Riasi 33o Munawwarwali- 33o - Jhelum Tawi Bhimber Chhamb Udhampur Akhnur- NW 605550 X International boundary Jammu INDIA - b Provincial boundary - na Gujrat he C - National capital Sialkot- Samba City, town or village Major road Kathua Line of Control as promulgated in the Lesser road 1972 SIMLA Agreement -- vi Airport Gujranwala Ra Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. 32o The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed 32o 0 25 50 75 km upon by the parties. -

समाचार पत्र से चियत अंश Newspapers Clippings

July 2020 समाचार पत्र से चियत अंश Newspapers Clippings A Daily service to keep DRDO Fraternity abreast with DRDO Technologies, Defence Technologies, Defence Policies, International Relations and Science & Technology Volume: 45 Issue: 15 0 July 2020 7 7 रक्षा िवज्ञान पुतकालय Defenceरक्षा िवज्ञान Science पुतकालय Library रक्षाDefence वैज्ञािनक सScienceूचना एवं प्रल Libraryेखन क द्र Defence Scientific Information & Documentation Centre रक्षा वैज्ञािनक सूचना एव ं प्रलेखन क द्र Defence Scientificमेटकॉफ Informationहाउस, िदली -& 110 Documentation 054 Centre Metcalfe House, Delhi - 110 054 मेटकॉफ हाउस, िदली - 110 054 Metcalfe House, Delhi- 110 054 CONTENT S. No. TITLE Page No. DRDO News 1-14 COVID-19: DRDO’s Contribution 1-5 1. उघाटन / डीआरडीओ ने 12 दन म तैयार कया 1 हजार बेड का अथाई कोवड अपताल, 1 गहृ मं ी और रामंी ने कया उघाटन 2. DRDO ने 12 दन म तैयार कया 1000 बतर क मता वाला COVID-19 का 2 अथाई अपताल, शाह-राजनाथ ने कया दौरा 3. Just within 12 days Sardaar patel Covid Hospital started functioning, Amit Shah 4 and Rajnath Singh visited hospital (Kannada News) 4. World’s biggest Corona Hospital inaugurated in Delhi (Telugu News) 5 5. DRDO का कारनामा, सफ 12 दन म बनाया 1000 बेड वाला कोवड अपताल 6 DRDO Technology News 7-14 6. Akash Missile: BDL signs contract for licence agreement & ToT with DRDO 7 7. -

HM 14 APRIL Page 3.Qxd

THE HIMALAYAN MAIL Q JAMMU Q WEDNESDAY Q APRIL 14, 2021 JAMMU & KASHMIR 3 Div Com visits Mukhdoom Sahab Siachen warriors celebrates ‘Siachen Day’ HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Shrine, Chatti Padshahi JAMMU, APR 13 On 13 April 2021, Siachen Gurudwara, Ganpatyar Temple Warriors celebrated the 37th Siachen Day with place for devotees, visiting tremendous zeal and enthu- during the festival days. siasm. Brigadier Gurpal He said that today's festi- Singh, SM laid a wreath on vals which are being cele- behalf of GOC, Fire & Fury brated with harmony and Corps and paid homage to brotherhood adds colour to the martyrs at the Siachen its festivity. He said these War Memorial, Base Camp festivals strengthen the to commemorate their bonds of love among people courage and fortitude in se- and nurture amity and har- curing the highest and cold- mony in J&K. est battlefield of the World. During the visit, the com- On this day in 1984, In- mittees of places apprised dian troops first unfurled not only in the face of enemy Soldier continues to guard Siachen Warriors who the Div Com about their is- the tri colour at Bilafond La but also in the face of icy the Frozen Frontier with de- served their motherland sues and demands. He gave launching Operation Megh- peaks with extreme termination and resolve while successfully thwarting HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Padshahi Rainawari and arrangements being put in patient hearing to them as- doot. Since then, it has been weather. against all odds. The enemy designs over the SRINAGAR, APR 13 extended his greetings on place for the Holy month of suring that all their genuine a saga of valour and audacity To this day, the Siachen Siachen Day honours all the years. -

India's Military Strategy Its Crafting and Implementation

BROCHURE ONLINE COURSE INDIA'S MILITARY STRATEGY ITS CRAFTING AND IMPLEMENTATION BROCHURE THE COUNCIL FOR STRATEGIC AND DEFENSE RESEARCH (CSDR) IS OFFERING A THREE WEEK COURSE ON INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. AIMED AT STUDENTS, ANALYSTS AND RESEARCHERS, THIS UNIQUE COURSE IS DESIGNED AND DELIVERED BY HIGHLY-REGARDED FORMER MEMBERS OF THE INDIAN ARMED FORCES, FORMER BUREAUCRATS, AND EMINENT ACADEMICS. THE AIM OF THIS COURSE IS TO HELP PARTICIPANTS CRITICALLY UNDERSTAND INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY INFORMED BY HISTORY, EXAMPLES AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE. LED BY PEOPLE WHO HAVE ‘BEEN THERE AND DONE THAT’, THE COURSE DECONSTRUCTS AND CLARIFIES THE MECHANISMS WHICH GIVE EFFECT TO THE COUNTRY’S MILITARY STRATEGY. BY DEMYSTIFYING INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY AND WHAT FACTORS INFLUENCE IT, THE COURSE CONNECTS THE CRAFTING OF THIS STRATEGY TO THE LOGIC BEHIND ITS CRAFTING. WHY THIS COURSE? Learn about - GENERAL AND SPECIFIC IDEAS THAT HAVE SHAPED INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY ACROSS DECADES. - INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS AND PROCESSES. - KEY DRIVERS AND COMPULSIONS BEHIND INDIA’S STRATEGIC THINKING. Identify - KEY ACTORS AND INSTITUTIONS INVOLVED IN DESIGNING MILITARY STRATEGY - THEIR ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES. - CAUSAL RELATIONSHIPS AMONG A MULTITUDE OF VARIABLES THAT IMPACT INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. Understand - THE REASONING APPLIED DURING MILITARY DECISION MAKING IN INDIA - WHERE THEORY MEETS PRACTICE. - FUNDAMENTALS OF MILITARY CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND ESCALATION/DE- ESCALATION DYNAMICS. - ROLE OF DOMESTIC POLITICS IN AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES ON INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. - THREAT PERCEPTION WITHIN THE DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT AND ITS MILITARY ARMS. Explain - INDIA’S MILITARY ORGANIZATION AND ITS CONSTITUENT PARTS. - INDIA’S MILITARY OPTIONS AND CONTINGENCIES FOR THE REGION AND BEYOND. - INDIA’S STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS AND OUTREACH. -

2019 年 6 月・中印・印パ国境辺境高地の旅 (Rev 2020 0602)

1 2019 年 6 月・中印・印パ国境辺境高地の旅 (REV 2020 0602) 付・ラダック北部とヌブラ谷地方の外国人旅行地域解放の最新情報 沖 允人(Masato OKI) (1) 天空の中印国境を行く 国境をめぐる争い 1962 年、インド北東部の Pangong Range(パンゴン山脈)の南東にある Chushul(4337m、チュスル、標高や地名綴 りは地図や文献により違うので以下は Leomann Map に準拠した)周辺、および、アクサイチンとチャンタン地区 (Aksaichin,Changthang Region)でインドと中国は、熾烈な戦いをした。発端は、中国側の主張は、インド側の兵士が Mcmahone Line(マクマホン・ライン・注1)の北側(中国側)に侵入したといい、インド側の主張は中国軍がインド領で ある東北辺境地区(NEFA,North-East Frontiea Agency・注 2)に侵攻したという、1956 年頃から続いているチベットを 巡る中国とインドとの対立の続きだといわれている。1962 年の戦いの結果はインド側の勝利に終わったが、インド側 は 1383 名、中国側は約 722 名の戦死者がでたという(中印国境紛争・Wikipedia)。 1947 年の第一次中印国境紛争後、Aksaichin に中国人民解放軍が侵攻、中華人民共和国が実効支配をするようにな ると、パキスタンもそれに影響を受け、間もなく、パキスタン正規軍も投入され、カシミール西部を中心に戦闘が行な われた。国際連合は 1948 年 1 月 20 日の国際連合安全保障理事会決議 39 でもって停戦を求めたが、戦争は継続され、 停戦となったのは 1948 年 12 月 31 日のことであった。停戦監視のため、国際連合インド・パキスタン軍事監視団 (UNMOGIP)が派遣されたが、恒久的な和平は結ばれず、1965 年に第二次印パ戦争が勃発することとなる。 1965 年 8 月にパキスタンは武装集団をインド支配地域へ送り込んだ。これにインド軍が反応し、1965 年、第二次 印パ戦争が勃発した。なお、その後、インドと中国・パキスタンの間で直接的な交戦は起こっていないが、中国による パキスタン支援は、インドにとって敵対性を持つものであった。2010 年 9 月にはインドは核弾頭の搭載が可能な中距 離弾道ミサイルをパキスタンと中国に照準を合わせて配備すると表明した。これらの戦争の結果、カシミールの 6 割 はインドの実効支配するところとなり、残りがパキスタンの支配下となった(第二次印パ戦争 Wikipedia)。最近のイ ンド・パキスタン情勢は「ヒマラヤ」489 号、2019 年・夏号・60-61 頁によると、印パ関係は悪化しているという。 以上のように、中印国境と印パ国境地帯をめぐる「天空の争い」は根が深く、現在は一応、平穏に見えているが、何 時この均衡が破れるかもしれないという、両国にとって気の抜けない地帯である。もちろん両国は、かなりの軍事施 設を国境地帯に構築し、多くの軍隊を駐屯させている。 このような状況から、インド政府は Chushul やその南東の中国国境に近い Hanle(4350m)とその周辺は外国人の立 ち入りを厳しく制限していた。 なお、2020 年 6 月 2 日の中日新聞朝刊 3 面の北京発の情報によると、中国がパンゴン湖の周辺などでインドに越境 して不穏に情勢だと報じている。 Hanle 解放のニュース 政情がどう変化したか察知できないが、2018 年末に、Hanle が外国人に開放されるというニュースが入り、2019 年 4 月から特別許可が発行されるという情報が、私の懇意にしているレーの旅行社 -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

Siachen: the Non-Issue, by Prakash Katoch

Siachen: The Non-Issue PC Katoch General Kayani’s call to demilitarise Siachen was no different from a thief in your balcony asking you to vacate your apartment on the promise that he would jump down. The point to note is that both the apartment and balcony are yours and the thief has no business to dictate terms. Musharraf orchestrated the Kargil intrusions as Vajpayee took the bus journey to Lahore, but Kayani’s cunning makes Musharraf look a saint. Abu Jundal alias Syed Zabiuddin an Indian holding an Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) provisioned Pakistani passport has spilled the beans on the 26/11 Mumbai terror attack: its complete planning, training, execution and minute-to-minute directions by the Pakistani military-ISI-LeT (Lashkar-e-Tayyeba) combine. More revealing is the continuing training for similar attacks under the marines in Karachi and elsewhere. The US says Pakistan breeds snakes in its backyard but Pakistan actually beds vipers and enjoys spawning more. If Osama lived in Musharraf’s backyard, isn’t Kayani dining the Hafiz Saeeds and Zaki-Ur- Rehmans, with the Hamid Guls in attendance? His demilitarisation remark post the Gyari avalanche came because maintenance to the Pakistanis on the western slopes of Saltoro was cut off. Yet, the Indians spoke of ‘military hawks’ not accepting the olive branch, recommending that a ‘resurgent’ India can afford to take chances in Siachen. How has Pakistan earned such trust? If we, indeed, had hawks, the cut off Pakistani forces would have been wiped out, following the avalanche. Kashmir Facing the marauding Pakistani hordes in 1947, when Maharaja Hari Singh acceded his state to India, Kashmir encompassed today’s regions of Kashmir Valley, Jammu, Ladakh (all with India), the Northern Areas, Gilgit-Baltistan, Lieutenant General PC Katoch (Retd) is former Director General, Information Systems, Army HQ and a Delhi-based strategic analyst. -

Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE for AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi

AIR POWER Journal of Air Power and Space Studies Vol. 3, No. 3, Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE FOR AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi AIR POWER is published quarterly by the Centre for Air Power Studies, New Delhi, established under an independent trust titled Forum for National Security Studies registered in 2002 in New Delhi. Board of Trustees Shri M.K. Rasgotra, former Foreign Secretary and former High Commissioner to the UK Chairman Air Chief Marshal O.P. Mehra, former Chief of the Air Staff and former Governor Maharashtra and Rajasthan Smt. H.K. Pannu, IDAS, FA (DS), Ministry of Defence (Finance) Shri K. Subrahmanyam, former Secretary Defence Production and former Director IDSA Dr. Sanjaya Baru, Media Advisor to the Prime Minister (former Chief Editor Financial Express) Captain Ajay Singh, Jet Airways, former Deputy Director Air Defence, Air HQ Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, former Director IDSA Managing Trustee AIR POWER Journal welcomes research articles on defence, military affairs and strategy (especially air power and space issues) of contemporary and historical interest. Articles in the Journal reflect the views and conclusions of the authors and not necessarily the opinions or policy of the Centre or any other institution. Editor-in-Chief Air Commodore Jasjit Singh AVSM VrC VM (Retd) Managing Editor Group Captain D.C. Bakshi VSM (Retd) Publications Advisor Anoop Kamath Distributor KW Publishers Pvt. Ltd. All correspondence may be addressed to Managing Editor AIR POWER P-284, Arjan Path, Subroto Park, New Delhi 110 010 Telephone: (91.11) 25699131-32 Fax: (91.11) 25682533 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.aerospaceindia.org © Centre for Air Power Studies All rights reserved. -

Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine

Realignment and Indian Airpower Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs requests a courtesy line. ith a shift in the balance of power in the Far East, as well as multiple chal- Wlenges in the wider international security environment, several nations in the Indo-Pacific region have undergone significant changes in their defense pos- tures. This is particularly the case with India, which has gone from a regional, largely Pakistan-focused, perspective to one involving global influence and power projection. This has presented ramifications for all the Indian armed services, but especially the Indian Air Force (IAF). Over the last decade, the IAF has been trans- forming itself from a principally army-support instrument to a broad spectrum air force, and this prompted a radical revision of Indian aipower doctrine in 2012. It is akin to Western airpower thought, but much of the latest doctrine is indigenous and demonstrates some unique conceptual work, not least in the way maritime air- power is used to protect Indian territories in the Indian Ocean and safeguard sea lines of communication. Because of this, it is starting to have traction in Anglo- American defense circles.1 The current Indian emphases on strategic reach and con- ventional deterrence have been prompted by other events as well, not least the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, which demonstrated that India lacked a balanced defense apparatus. -

6 Nights & 7 Days Leh – Nubra Valley (Turtuk Village)

Jashn E Navroz | Turtuk, Ladakh | Dates 25March-31March’18 |6 Nights & 7 Days Destinations Leh Covered – Nubra : Leh Valley – Nubra (Turtuk Valley V illage)(Turtuk– Village Pangong ) – Pangong Lake – Leh Lake – Leh Trip starts from : Leh airport Trip starts at: LehTrip airport ends at |: LehTrip airport ends at: Leh airport “As winter gives way to spring, as darkness gives way to light, and as dormant plants burst into blossom, Nowruz is a time of renewal, hope and joy”. Come and experience this festive spirit in lesser explored gem called Turtuk. The visual delights would be aptly complemented by some firsthand experiences of the local lifestyle and traditions like a Traditional Balti meal combined with Polo match. During the festival one get to see the flamboyant and vibrant tribe from Balti region, all dressed in their traditional best. Day 01| Arrive Leh (3505 M/ 11500 ft.) Board a morning flight and reach Leh airport. Our representative will receive you at the terminal and you then drive for about 20 minutes to reach Leh town. Check into your room. It is critical for proper acclimatization that people flying in to Leh don’t indulge in much physical activity for at least the first 24hrs. So the rest of the day is reserved for relaxation and a short acclimatization walk in the vicinity. Meals Included: L & D Day 02| In Leh Post breakfast, visit Shey Monastery & Palace and then the famous Thiksey Monastery. Drive back and before Leh take a detour over the Indus to reach Stok Village. Enjoy a traditional Ladakhi meal in a village home later see Stok Palace & Museum.