Three Visions of Rimo III 8000Ers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications By Name: Syeda Batool National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 1 The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications by Name: Syeda Batool M.Phil Pakistan Studies, National University of Modern Languages, 2019 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY in PAKISTAN STUDIES To FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF PAKISTAN STUDIES National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 @Syeda Batool, April 2019 2 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THESIS/DISSERTATION AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Social Sciences for acceptance: Thesis/ Dissertation Title: The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications Submitted By: Syed Batool Registration #: 1095-Mphil/PS/F15 Name of Student Master of Philosophy in Pakistan Studies Degree Name in Full (e.g Master of Philosophy, Doctor of Philosophy) Degree Name in Full Pakistan Studies Name of Discipline Dr. Fazal Rabbi ______________________________ Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Prof. Dr. Shahid Siddiqui ______________________________ Signature of Dean (FSS) Name of Dean (FSS) Brig Muhammad Ibrahim ______________________________ Name of Director General Signature of -

Download Deployment Map.Pdf

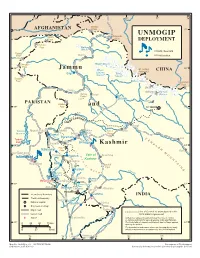

73o 74o 75o 76o 77o 78o Mintaka 37o AFGHANISTAN Pass 37o --- - UNMOGIP Darkot Khunjerab Pass Pass DEPLOYMENT - Thui- An Pass Batura- Glacier UN HQ / Rear HQ Chumar Khan- Baltit UN field station Pass Shandur- Hispar Glacier Pass 36o 36o Jammu Chogo Mt. Godwin CHINA Lungma Austin (K2) Gilgit Biafo 8611m Glacier Glacier Dadarili Baltoro Glacier Pass Karakoram Pass Sia La - Chilas Bilafond La Siachen Nanga Astor Glacier Parbat -- 8126m Skardu PAKISTAN Goma Babusar-- 35o Pass and 35o NJ 980420 X Kel ONTR C O F L LINE O - s a r Kargil D Tarbela Muzaffarabad- Tithwal- Wular Zoji La Dras- Reservoir Sopur Lake Pass Domel J h Jhe ---- e am Baramulla a m Z - Leh Tarbela A Dam Uri Srinagar- N Chakothi Kashmir S o o 34 K - 34 Haji-- Pir A - R Rawalakot Pass P - - - i- Karu Campbellpore Islamabad r M - O Titrinot P Vale of Anantnag Islamabad--- Poonch U a Kashmir N Mendhar n T Rawalpindi- Kotli j - A a- Banihal I ch l Pass N - n u R S P Rajouri C a n hen - Mangla g e ab Reservoir Naushahra- - Mangla Dam New Mirpur- Riasi 33o Munawwarwali- 33o - Jhelum Tawi Bhimber Chhamb Udhampur Akhnur- NW 605550 X International boundary Jammu INDIA - b Provincial boundary - na Gujrat he C - National capital Sialkot- Samba City, town or village Major road Kathua Line of Control as promulgated in the Lesser road 1972 SIMLA Agreement -- vi Airport Gujranwala Ra Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. 32o The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed 32o 0 25 50 75 km upon by the parties. -

HM 14 APRIL Page 3.Qxd

THE HIMALAYAN MAIL Q JAMMU Q WEDNESDAY Q APRIL 14, 2021 JAMMU & KASHMIR 3 Div Com visits Mukhdoom Sahab Siachen warriors celebrates ‘Siachen Day’ HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Shrine, Chatti Padshahi JAMMU, APR 13 On 13 April 2021, Siachen Gurudwara, Ganpatyar Temple Warriors celebrated the 37th Siachen Day with place for devotees, visiting tremendous zeal and enthu- during the festival days. siasm. Brigadier Gurpal He said that today's festi- Singh, SM laid a wreath on vals which are being cele- behalf of GOC, Fire & Fury brated with harmony and Corps and paid homage to brotherhood adds colour to the martyrs at the Siachen its festivity. He said these War Memorial, Base Camp festivals strengthen the to commemorate their bonds of love among people courage and fortitude in se- and nurture amity and har- curing the highest and cold- mony in J&K. est battlefield of the World. During the visit, the com- On this day in 1984, In- mittees of places apprised dian troops first unfurled not only in the face of enemy Soldier continues to guard Siachen Warriors who the Div Com about their is- the tri colour at Bilafond La but also in the face of icy the Frozen Frontier with de- served their motherland sues and demands. He gave launching Operation Megh- peaks with extreme termination and resolve while successfully thwarting HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Padshahi Rainawari and arrangements being put in patient hearing to them as- doot. Since then, it has been weather. against all odds. The enemy designs over the SRINAGAR, APR 13 extended his greetings on place for the Holy month of suring that all their genuine a saga of valour and audacity To this day, the Siachen Siachen Day honours all the years. -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan

The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan PhD Thesis Submitted by Ehsan Mehmood Khan, PhD Scholar Regn. No. NDU-PCS/PhD-13/F-017 Supervisor Dr Muhammad Khan Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Faculties of Contemporary Studies (FCS) National Defence University (NDU) Islamabad 2017 ii The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan PhD Thesis Submitted by Ehsan Mehmood Khan, PhD Scholar Regn. No. NDU-PCS/PhD-13/F-017 Supervisor Dr Muhammad Khan This Dissertation is submitted to National Defence University, Islamabad in fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Studies Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Faculties of Contemporary Studies (FCS) National Defence University (NDU) Islamabad 2017 iii Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for Doctor of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Department NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY Islamabad- Pakistan 2017 iv CERTIFICATE OF COMPLETION It is certified that the dissertation titled “The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan” written by Ehsan Mehmood Khan is based on original research and may be accepted towards the fulfilment of PhD Degree in Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS). ____________________ (Supervisor) ____________________ (External Examiner) Countersigned By ______________________ ____________________ (Controller of Examinations) (Head of the Department) v AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis titled “The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan” is based on my own research work. Sources of information have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. -

Akhilesh Detained, BJP Ally Announces Cms of BJP-Ruled States Lead Attack March As Oppn Rallies Behind Farmers

DAILY FROM: AHMEDABAD, CHANDIGARH, DELHI, JAIPUR, KOLKATA, LUCKNOW, MUMBAI, NAGPUR, PUNE, VADODARA JOURNALISM OF COURAGE TUESDAY, DECEMBER 8, 2020, KOLKATA, LATE CITY, 12 PAGES SINCE 1932 `5.00/EX-KOLKATA `6.00(`12INNORTH EAST STATES&ANDAMAN)WWW.INDIANEXPRESS.COM Army got politicalsignal NEW PARLIAMENT First details of to identify, occupy ‘6-7 CentralVista:SC immunisation locations’ on LAC in May emerge: shots in batches of vred Chinese troops in August- cautions,makes KRISHNKAUSHIK end to occupythe heights, includ- NEWDELHI,DECEMBER7 ing Mukhpari, Rezang La, Rechin 100 people; 30 La andGurung Hillamongothers, THEARMY'S move to occupy and the south bank of Pangong Govthitpause minutes each dominantheights in theChushul Tsointhe sub-sector. sub-sectorand bolsterits position The political leadership “had in the border face-offwith China giveninstructions to the forces No work until pleas decided, cango KAUNAINSHERIFFM in eastern Ladakhwastaken after in Mayitself, to identifysix to Farmersatthe Singhu border in NewDelhi on Monday. Praveen Khanna NEWDELHI,DECEMBER7 apolitical go-ahead in Maytooc- sevenlocations wherewecan ahead withDec 10 foundation laying cupy“six to sevenlocations” go”, the official said. Underlining ■100individuals will be admin- along the Line of Actual Control the significance of these posi- isteredthe vaccine duringeach (LAC), asenior government offi- tions, the official said severalof Ahead of Bharat bandh today, war EXPRESSNEWSSERVICE ED session at avaccination centre. cial told The Indian Express. them arebeyondthe LAC. “It has NEWDELHI,DECEMBER7 Onhold ■ The vaccinator will take at Following these directions, givenIndia something to bargain PLAIN E least30minutes to complete the ● fornow the topofficial said, theArmyfor- with,” the official said. of words betweenBJP, Congress EXPRESSINGITS concern at the EX process of vaccinating eachre- mulated plans and outmanoeu- CONTINUEDONPAGE2 Government proceeding “ag- cipient,toensuretracking of a gressively” with the Central Vista THE SUPREMECourtor- possible adverseevent. -

Factsthat Led to the Creation of Pakistan

AVAIL YOUR COPY NOW! April-July 2020 Volume 17 No. 2-3 `100.00 (India-Based Buyer Only) SP’s Military Yearbook 2019 SP’s AN SP GUIDE P UBLICATION www.spsmilitaryyearbook.com WWW.SPSLANDFORCES.COM ROUNDUP THE ONLY MAGAZINE IN ASIA-PACIFIC DEDICATED to LAND FORCES IN THIS ISSUE >> LEAD STORY ILLuSTratioN: SP Guide Publications / Vipul PAGE 3 Lessons from Ladakh Standoff Wakhan Corridor Territory ceded We keep repeating the mistakes. The by Pakistan to CLASHES ALONG Chinese PLA incursion in Ladakh, across the China in 1963 LAC, has been again a collective intelligence (Shaksgam Valley) failure for India. There is much to be CHINA THE LAC learned for India from the current scenario. Teram Shehr Lt General P.C. Katoch (Retd) May 5 Indian and Gilgit Siachen Glacier Chinese soldiers PAGE 4 Pakistan clash at Pangong TSO lake. Disengagement to Demobilisation: Occupied Karakorm Resetting the Relations Pass May 10 Face-off at China is a master of spinning deceit Kashmir the Muguthang Valley and covert action exploiting strategy Baltistan in Sikkim. Skardu and statecraft as means of “Combative Depsang La May 21 Chinese coexistence” with opponents. Throughout Bilafond La NJ 9842 Aksai Chin troops enter into the their history Chinese have had their share Patrol Galwan River Valley of brutal conflicts at home and with Point 14 in Ladakh region. neighbours. LOC Zoji La Kargil Nubra Valley Galwan Valley May 24 Chinese Lt General J.K. Sharma (Retd) Line Of Pangong-TSO camps at 3 places: Control Leh Lake Hotspring, P14 and PAGE 5 P15. Way Ahead for the Indian Armed Forces Jammu & Shyok LADAKH June 15 Violent Face- Kashmir off” between Indian and Chinese Soldiers. -

A Siachen Peace Park?

HARISH KAPADIA A Siachen Peace Park? e were staying in army bunkers at base camp on the Siachen glacier. W In the next room I could hear my son, Nawang, then a young man of 20 years, talking with equally young lieutenants and captains of the Indian army. They were discussing their exploits on the glacier, the war and agitatedly talking about the friends being wounded and killed all around them. One well-meaning officer pointedly said to me as I entered the room to join the discussion: 'I am ready to fight for my country and defend the Siachen. But sir, I am young and I do not want my children and grand-children sitting on this high, forlorn Saltoro ridge defending the Siachen glacier. Why can't we have some solution to this wretched problem?' Another young officer added: 'Look at the glacier, a pristine mountain area polluted almost beyond repair. It will take decades, if not a century to rejuvenate. Something must be done.' These dedicated officers of the Indian army left the seed of an idea in my mind. This world is a legacy for the young, an area like Siachen belongs to them. They were ready to guard it with their lives; they meant well. My son, excited at the prospect of defending his country alongside other officers, had worked hard andjoined the army as a Gorkha Officer. Shortly thereafter he fell to a terrorist bullet in this bloody war in Kashmir. That seed of an idea became a raison d 'etre of my life. -

Volume 27 # June 2013

THE HIMALAYAN CLUB l E-LETTER Volume 27 l June 2013 Contents Annual Seminar February 2013 ........................................ 2 First Jagdish Nanavati Awards ......................................... 7 Banff Film Festival ................................................................. 10 Remembrance George Lowe ....................................................................................... 11 Dick Isherwood .................................................................................... 3 Major Expeditions to the Indian Himalaya in 2012 ......... 14 Himalayan Club Committee for the Year 2013-14 ........... 28 Select Contents of The Himalayan Journal, Vol. 68 ....... 30 THE HIMALAYAN CLUB l E-LETTER The Himalayan Club Annual Seminar 2013 The Himalayan Club Annual Seminar, 03 was held on February 6 & 7. It was yet another exciting Annual Seminar held at the Air India Auditorium, Nariman Point Mumbai. The seminar was kicked off on 6 February 03 – with the Kaivan Mistry Memorial Lecture by Pat Morrow on his ‘Quest for the Seven and a Half Summits’. As another first the seminar was an Audio Visual Presentation without Pat! The bureaucratic tangles had sent Pat back from the immigration counter of New Delhi Immigration authorities for reasons best known to them ! The well documented AV presentation made Pat come alive in the auditorium ! Pat is a Canadian photographer and mountain climber who was the first person in the world to climb the highest peaks of seven Continents: McKinley in North America, Aconcagua in South America, Everest in Asia, Elbrus in Europe, Kilimanjaro in Africa, Vinson Massif in Antarctica, and Puncak Jaya in Indonesia. This hour- long presentation described how Pat found the resources to help him reach and climb these peaks. Through over an hour that went past like a flash he took the audience through these summits and how he climbed them in different parts of the world. -

Demilitarization of Siachen Glacier and Its Implications on the Defence Budget of Pakistan

Journal of Politics and International Studies Vol. 2, No. 1, January –June 2016, pp. 01– 12 Demilitarization of Siachen Glacier and Its Implications on the Defence Budget of Pakistan Sanam Ahmed Khawaja PhD Scholar Department of Political Science, University of the Punjab, Lahore ABSTRACT This research paper focuses on demilitarization of Siachen Glacier and its implications on the defence budget of Pakistan. The government of India and Pakistan are hiking the defence budget to an extreme and in particular for Siachen that consequently it reveals that the glacier of Siachen retain massive geo- strategic significance for both the states. The data has been collected from primary and secondary sources. Moreover theory of disarmament has been adopted by the researcher in relation to Siachen conflict. An interview was conducted from military personnel to get aware of military’s stance with reference to Siachen Glacier. Thus it has been concluded that mutually both the states ought to look for an amicable solution as regard to glacier’s demilitarization furthermore generate a balance between defence and other main sectors so they might not face any negligence. Keywords: Budget of Pakistan, Siachen Glacier, Demilitarization Introduction Geographical Location of the Glacier Siachen Glacier said to be as the “world’s highest battlefield” is ranked as the second longest non- polar glacier after the Fedchenko Glacier in the Pamir which is 77km long. The 70km long glacier of Siachen is located in the Eastern Karakoram Range and width of it lies in between 2 to 8 km and total area is less than 1,000sq km. -

On the Death Trail

HARISH KAPADIA On the Death Trail A Journey across the Shyok and Nubra valleys ater levels in the Shyok were rising and within a week our route W would be closed. It was 17 May 2002 and we had arrived in Shyok village just in the nick of time. The trail from here to the Karakoram Pass is known as the 'Winter Trail' as it is only in that season that the Shyok river is crossable. The name itself carries a warning: in Ladakhi 5hi means 'death' and yak means 'river', literally the 'the river of death'. It has to be crossed 24 times and many travellers have perished in its floods. Our party comprised five Japanese and six Indian mountaineers accompanied by an army liaison officer. We were at the start of a long journey covering the two large valleys of the Shyok and the Nubra rivers, in Ladakh, East Karakoram. It is forbidding terrain. Our ambitious plan was to follow the Shyok, visit the Karakoram Pass, cross the Col Italia, explore the Teram Shehr plateau and finally descend via the Siachen glacier. In between all this, we planned to climb the virgin peak Padmanabh (7030m). Back in the 19th century, the British tried to build a formal trail here by blasting rocks on the left bank in order to minimise the crossings. We could see blast marks on the rocks, though at many places our own trail was on the opposite bank. The project was abandoned and Ladakhi caravans continue to use the traditional route, crossing and re-crossing the Shyok five or six times each day. -

Glacier Exploration in the Eastern Karakoram Author(S): T

Glacier Exploration in the Eastern Karakoram Author(s): T. G. Longstaff Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 35, No. 6 (Jun., 1910), pp. 622-653 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1777235 Accessed: 18-06-2016 22:07 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 130.113.111.210 on Sat, 18 Jun 2016 22:07:13 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms ( 622 ) GLACIER EXPLORATION IN THE EASTERN KARAKORAM.* By T. G. LONGSTAFF, M.A., M.D. Oxon. OF the mountain regions of High Asia which are politically acces- sible to the ordinary traveller, there is none' concerning which detailed information is more scanty than the eastern section of the great Kara- koram range. Between Younghusband's MIuztagh pass andc the Kara- koram pass on the Leh-Yarkand trade-route, a distance of 100 miles as the crow flies, we have no record of any passage across the main axis of elevation having ever been effected by a European.