Household Finance: an Emerging Field1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborate, Understand, Innovate

Collaborate, understand, innovate. 2013 Reports and Accounts his report describes the work that the UniCredit & Universities Foundation is doing to support the studies and research of TEurope’s brightest young minds. It details the full range of programs implemented by the foundation to assist promising young people develop original ideas in the fields of economics and finance. Collaboration, understanding, innovation, facilitation, selectivity and responsiveness are all key aspects of the UniCredit & Universities mission. These words express the motivations that underlie the foundation’s programs for students and researchers who want to make a difference. The foundation is committed to providing them with concrete solutions and tangible benefits that can clear a pathway to their future careers. At the heart of its activities, UniCredit & Universities listens closely to its scholars and fellows to ensure that it can provide them with direct and effective support. This is a vital part of the process of enabling them to focus on their work at the world’s best academic institutions. The foundation seeks to make these opportunities available to students and researchers in every community where UniCredit is present. Inside this report, you will find the full record of the activities and ideals embraced by UniCredit & Universities. The stories and statistics it contains are intended to further enhance foundation’s relationship with all of its stakeholders and reaffirm its commitment to its work. 2013 Reports and Accounts Collaborate Working more efficiently, with better results Effective academic work requires a willingness and an ability to interact well with everyone in the university environment. At UniCredit & Universities, collaboration is not only a way of working but also a mindset. -

Adam Smith's Library”

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: https://journaltalk.net/articles/5990/ ECON JOURNAL WATCH 16(2) September 2019: 374–474 Foreword and Supplement to “Adam Smith’s Library: General Check-List and Index” Daniel B. Klein1 and Andrew G. Humphries2 LINK TO ABSTRACT To dwell in Adam Smith’s thought one places him in history and streams of discourse. We learn a bit about his personage from contemporary memoirs and accounts, his personal communications from his correspondence, and his influences from the allusions and references in his work. Also useful is the catalogue of his personal library. He did not much write inside the books he owned (Phillipson et al. 2019; Simpson 1979, 191), but Smith scholars use the listing of his personal library in interpreting his thought. The cataloguing of books belonging to Adam Smith has been the work of numerous scholars, the two chief figures being James Bonar (1852–1941) and Hiroshi Mizuta, who in September 2019 reached the age of 100 years. To aid scholarship, we here reproduce the checklist created by Mizuta (1967). We gratefully acknowledge the permission of both Professor Mizuta and the Royal Economic Society, which holds copyright. The 1967 checklist has been bettered, notably by Mizuta’s own complete account represented by Mizuta (2000). That work, however, does not lend itself to a handy checklist to be reproduced online. When Mizuta made the 1967 checklist, those of Smith’s books held by the University of Edinburgh had not all been recognized as such. When a librarian has a volume in hand, nearly the only way to determine that it had been in Smith’s library is by the presence of his bookplate, shown below. -

Da Vinci Code Research

The Da Vinci Code Personal Unedited Research By: Josh McDowell © 2006 Overview Josh McDowell’s personal research on The Da Vinci Code was collected in preparation for the development of several equipping resources released in March 2006. This research is available as part of Josh McDowell’s Da Vinci Pastor Resource Kit. The full kit provides you with tools to equip your people to answer the questions raised by The Da Vinci Code book and movie. We trust that these resources will help you prepare your people with a positive readiness so that they might seize this as an opportunity to open up compelling dialogue about the real and relevant Christ. Da Vinci Pastor Resource Kit This kit includes: - 3-Part Sermon Series & Notes - Multi-media Presentation - Video of Josh's 3-Session Seminar on DVD - Sound-bites & Video Clip Library - Josh McDowell's Personal Research & Notes Retail Price: $49.95 The 3-part sermon series includes a sermon outline, discussion points and sample illustrations. Each session includes references to the slide presentation should you choose to include audio-visuals with your sermon series. A library of additional sound-bites and video clips is also included. Josh McDowell's delivery of a 3-session seminar was captured on video and is included in the kit. Josh's personal research and notes are also included. This extensive research is categorized by topic with side-by-side comparison to Da Vinci claims versus historical evidence. For more information and to order Da Vinci resources by Josh McDowell, visit josh.davinciquest.org. http://www.truefoundations.com Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction: The Search for Truth.................................................................................. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Essays on Monetary Economics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/38m8q6qh Author Wu, Wenbin Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Essays on Monetary Economics A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics by Wenbin Wu Committee in charge: Professor James Hamilton, Chair Professor Thomas Baranga Professor David Lagakos Professor Rossen Valkanov Professor Johannes Wieland 2017 Copyright Wenbin Wu, 2017 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Wenbin Wu is approved and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Table of Contents . iv List of Figures . vi List of Tables . vii Acknowledgements . viii Vita................................................................. ix Abstract of the Dissertation . x Chapter 1 Sales, Monetary Policy, and Durable Goods . 1 1.1 Data......................................................... 6 1.1.1 Descriptive Statistics . 7 1.2 Sales and Inflation . 8 1.2.1 Do Sales Respond to Aggregate Shocks? . 10 1.2.2 Aggregate Inflation and Sales . 13 1.3 A Two-sector Menu-cost Model . 16 1.3.1 Model Setup . 17 1.3.2 Computation Method . 22 1.3.3 Model Calibration . 24 1.4 Results . 26 1.5 Conclusions . 30 1.6 Acknowledgements . 30 Chapter 2 The Credit Channel at the Zero Lower Bound Through the Lens of Equity Prices . 31 2.1 Data and Reexamination . 34 2.1.1 Data . -

The Analytic Theory of a Monetary Shock Fernando E

WORKING PAPER · NO. 2021-21 The Analytic Theory of a Monetary Shock Fernando E. Alvarez and Francesco Lippi FEBRUARY 2021 5757 S. University Ave. Chicago, IL 60637 Main: 773.702.5599 bfi.uchicago.edu THE ANALYTIC THEORY OF A MONETARY SHOCK Fernando E. Alvarez Francesco Lippi February 2021 The first draft of this paper is from March 2018, which is 250 years after the birthdate of Jean Baptiste Fourier, from whose terrific 1822 book we respectfully adapted our title. We benefited from conversations with Isaac Baley, Lars Hansen, and Demian Pouzo. We also thank our discussants Sebastian Di Tella and Ben Moll, and participants in “Recent Developments in Macroeconomics” conference (Rome, April 2018), the “Second Global Macroeconomic Workshop” (Marrakech), the 6th Workshop in Macro Banking and Finance in Alghero, and seminar participants at the FBR of Minneapolis and Philadelphia, the European Central Bank, LUISS University, UCL, EIEF, the University Di Tella, Northwestern University, the University of Chicago, the University of Oxford, CREI-UPF, the London School of Economics, Universitat Autonoma Barcelona, Bocconi University, and the 2019 EFG meeting in San Francisco. © 2021 by Fernando E. Alvarez and Francesco Lippi. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Analytic Theory of a Monetary Shock Fernando E. Alvarez and Francesco Lippi February 2021 JEL No. E5,E50 ABSTRACT We propose an analytical method to analyze the propagation of a once-and-for-all shock in a broad class of sticky price models. -

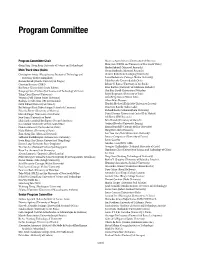

Program Committee

Program Committee Program Committee Chair Mauricio Ayala-Rincón (Universidade de Brasilia) Qiang Yang (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) Haris Aziz (NICTA and University of New South Wales) Moshe Babaioff (Microso Research) Main Track Area Chairs Yoram Bachrach (Microso Research) Christopher Amato (Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Christer Bäckström (Linköping University) University of New Hampshire) Laura Barbulescu (Carnegie Mellon University) Roman Bartak (Charles University in Prague) Pablo Barcelo (Universidad de Chile) Christian Bessiere (CNRS) Leliane N. Barros (University of Sao Paulo) Blai Bonet (Universidad Simón Bolívar) Peter Bartlett (University of California, Berkeley) Xiaoping Chen (University of Science and Technology of China) Shai Ben-David (University of Waterloo) Yiling Chen (Harvard University) Ralph Bergmann (University of Trier) Veronica Dahl (Simon Fraser University) Alina Beygelzimer (Yahoo! Labs) Rodrigo de Salvo Braz (SRI International) Albert Bifet (Huawei) Edith Elkind (University of Oxford) Hendrik Blockeel (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) Boi Faltings (Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne) Francesco Bonchi (Yahoo Labs) Eduardo Ferme (University of Madeira) Richard Booth (Mahasarakham University) Marcelo Finger (University of Sao Paulo) Daniel Borrajo (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid) Joao Gama (University of Porto) Adi Botea (IBM Research) Lluis Godo (Artificial Intelligence Research Institute) Felix Brandt (University of Munich) Jose Guivant (University of New South Wales) Gerhard -

The Real Effects of Monetary Shocks: Evidence from Micro Pricing Moments

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper Series The Real Effects of Monetary Shocks: Evidence from Micro Pricing Moments Gee Hee Hong, Matthew Klepacz, Ernesto Pasten, and Raphael Schoenle Working Paper No. 21-17 September 2021 Suggested citation: Hong, Gee Hee, Matthew Klepacz, Ernesto Pasten, and Raphael Schoenle. 2021. “The Real Effects of Monetary Shocks: Evidence from Micro Pricing Moments.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Working Paper No. 21-17. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-wp-202117. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper Series ISSN: 2573-7953 Working papers of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment on research in progress. They may not have been subject to the formal editorial review accorded official Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland publications. See more working papers at: www.clevelandfed.org/research. Subscribe to email alerts to be notified when a new working paper is posted at: www.clevelandfed.org/subscribe. The Real Effects of Monetary Shocks: Evidence from Micro Pricing Moments Gee Hee Hong,∗ Matthew Klepacz,† Ernesto Pasten,‡ and Raphael Schoenle§ This version: July 2021 Abstract This paper evaluates the informativeness of eight micro pricing moments for monetary non-neutrality. Frequency of price changes is the only robustly informative moment. The ratio of kurtosis over frequency is significant only because of frequency, and insignificant when non-pricing moments are included. Non-pricing moments are additionally informative about monetary non-neutrality, indicating potential omitted variable bias and the inability of pricing moments to serve as sufficient statistics. In contrast to existing theoretical work, this ratio has an ambiguous relationship with monetary non-neutrality in a quantitative menu cost model. -

Three Essays on the Macroeconomic Consequences of Prices

Three Essays on the Macroeconomic Consequences of Prices by DongIk Kang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Economics) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Christopher L. House, Chair Professor Julio A. Blanco Professor Joshua K. Hausman Professor Miles S. Kimball, University of Colorado Professor John V. Leahy DongIk Kang [email protected] ORCID ID 0000-0003-2716-9853 © DongIk Kang 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor Chris House for his contin- ued guidance and support throughout my Ph.D. I was privileged to have him as my advisor. I also thank my committee members, John Leahy, Andres Blanco, Joshua Hausman and Miles Kimball for their insightful comments and sup- port. Alberto Arredondo, Jacob Bastian, Aakash Mohpal, Richard Ryan and Andrew Usher provided moral support as well as academic insights. Finally, I am heavily indebted to my family, in particular to my wife Naewon, for their unconditional support. The first chapter of this dissertation is co-authored with Andrew Usher. The second chapter is co-authored with Miles S. Kimball. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ....................................... ii List of Figures ......................................... v List of Tables .......................................... vii List of Appendices ....................................... viii Abstract ............................................. ix Chapter 1 Product Revenue and Price Setting: Evidence and Aggregate Implications ...... 1 1.1 Introduction.....................................1 1.2 Revenue and Price Setting.............................5 1.2.1 Data.....................................5 1.2.2 Empirical Findings.............................7 1.2.3 A Menu Cost Interpretation........................ 14 1.3 State-Dependence of Monetary Policy....................... 18 1.3.1 The Revenue Effect............................ -

The Romance of Sandro Botticelli Woven with His Paintings

THE ROMANCE OF SANDRO BOTTICELLI T« nIw yorc PUBUC UBRART «*^- —^.—.^ ,»„_,— ^1 t^y^n^y^n^€-.^^59i^^€i!/yi^/ta,. THE ROMANCE OF SANDRO BOTTICELLI WOVEN FROM HIS PAINTINGS BY A. J. ANDERSON Author o( "The Romance 6t Fra Filippo Lippi,'* etc. V- WITH PHOTOGRAVURE FRONTISPIECE AND NINETEEN OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS NEW YORK DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY 1912 !^\>S YV- PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN — PREFACE HE who would write the account of a Tuscan of the Quattrocento will find that there are two just courses open to him : he may compile a scientific record of bare facts and contemporary refer- ences, without a word of comment, or else he may tell his story in the guise of fiction. The common practice of writing a serious book, rooted on solid facts, and blossoming out into the author's personal deductions as to character and motives, is a monstrous injustice—the more authori- tative the style, the worse the crime—for who can judge the character and motives of even a contem- porary ? Besides, such works stand self-condemned, since the serious books and articles on Sandro Botti- celli, written during the past twenty years, prove beyond a doubt {a) That he was a deeply religious man, permeated with the rigorism of Savonarola, and groaning over the sins of Florence ; That he a (J?) was semi-pagan ; (r) That he was a philosopher, who despaired of reconciling Christianity with classicalism ; 5 6 Preface {d) That he was an ignorant person, who knew but little of those classical subjects which he took from the poems of Lorenzo and Politian ; ((?) That he was a deep student and essayist on Dante ; (/) That he was a careless fellow, with no thoughts beyond the jest and bottle. -

Bibliotheken Van VUBIS-Antwerpen Aanwinstenlijst

Bibliotheken van VUBIS-Antwerpen Aanwinstenlijst september 1997 ERL-Server (UA Medline bij. Zeer waarschijnlijk worden later ook Econlit en MathSci aangeboden. Over de zomer installeerden de bibliotheken van de UA en het LUC de ERL-server van SilverPlatter. De ERL server is vanaf 1 oktober beschikbaar op ERL staat voor Electronic Reference Library. Het http://biblio.luc.ac.be/webspirs/webspirs.html. gaat om een technologie waarmee databanken van SilverPlatter via het Web kunnen worden Informatie 97 (Brussel) geraadpleegd. Op 17 en 18 september had in de Koninklijke ERL aanbod van de UA-bibliotheken Bibliotheek Albert I de beurs Informatie 97 plaats. Deze beurs werd georganiseerd door de Vlaamse Elkeen die aangesloten is op de campusnetwerken van Vereniging voor Bibliotheek-, Archief- en RUCA, UFSIA of UIA kan via het Web de ERL Documentatiewezen. De UA-bibliotheken waren op databanken ondervragen. Op dit ogenblik worden deze beurs vertegenwoordigd met een stand waarop door de UA volgende databanken aangeboden: diverse diensten werden gedemonstreerd: de Web · Econlit OPAC, Impala, Agrippa, ERL-databanken, het · Medline VirLib-project ... Verder verzorgden een aantal · Sociofile medewerkers voordrachten over lopende projecten · Union catalogue of Belgian research libraries van de UA-bibliotheken. Johan van Hecke (AMVC) Later op het jaar komen daar nog bij: gaf een lezing over Agrippa: de sleutel op het AMVC, · Books in print Jan Corthouts (UIA) kwam aan het woord over het · Eric: Onderwijs VirLib project en Richard Philips (UA) rapporteerde · LISA: Library and information science abstracts over de automatisering van de openbare bibliotheken · MLA: Modern language abstracts van de Stad Antwerpen. Tenslotte verzorgden Peter Van Landegem (UFSIA), Frank Van der Auwera De ERL server vindt u op: (UIA) en Luc Bastiaenssen een vraag- en http://erl.ua.ac.be/webspirs/webspirs.html. -

The Medium-Term Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions

LIEPP Working Paper October 2020, nº112 The medium-term impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions. The case of the 1918 Influenza in U.S. cities Guillaume CHAPELLE CY Cergy Paris-Université, LIEPP [email protected] www.sciencespo.fr/liepp © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. How to cite this publication: CHAPELLE, Guillaume, The medium-term impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions. The case of Influenza in U.S. cities, Sciences Po LIEPP Working Paper n°112, 2020-10-22. The medium-term impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions. The case of the 1918 Influenza in U.S. cities ∗ Guillaume Chapelle † First version April 11, 2020; this version October, 2020 Abstract This paper uses a difference-in-differences (DID) framework to estimate the impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) used to fight the 1918 influenza pandemic and control the resultant mortality in 43 U.S. cities. The results suggest that NPIs such as school closures and social distancing, as implemented in 1918, and when applied for a relatively long and sustained time, might have reduced individual and herd immunity and the population general health condition, thereby leading to a significantly higher number of deaths in subsequent years. J.E.L. Codes: I18, H51, H84 Keywords: Non-pharmaceutical interventions, 1918 influenza, difference-in-differences, health policies ∗The author acknowledges support from ANR-11-LABX-0091 (LIEPP), ANR-11-IDEX-0005- 02 and ANR-17-CE41-0008 (ECHOPPE). I thank Pierre Andr´e,Richard Baldwin, Sara Biancini, Sarah Cohen, Sergio Correa, Ma¨elysde la Rupelle, Rebecca Diamond, Jean Beno^ıtEym´eoud, Maud Giacopelli, Laurent Gobillon, Pierrick Gouel, Laurence Jacquet, Andrew Liley, Matthew Liley, Philippe Martin, Gianlucca Rinaldi, Alain Trannoy, Etienne Wasmer, Clara Wolf, Charles Wyplosz and participants to the THEMA Lunch seminar for their helpful comments on this working paper. -

4.3. Athens Laboratory of Research in Marketing - ALARM

ATHENS UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS (AUEB) RESEARCH LABORATORIES 2009 RESEARCH LABORATORIES Research Laboratories A Bridge to Partnership in Research ATHENS UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS (AUEB) HENS UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS (AUEB) AT 76, Patission str, GR-104 34 Athens, Greece Tel.: +30 210 8203911, +30 210 8203200 ñ Fax: +30 210 8226204, +30 210 8228419 http://www.aueb.gr ñ E-mail: [email protected] International Relations Office ñ Tel.: +30 210 8203250 - 270 ñ Fax: +30 210 8228419 ñ E-mail: [email protected] Public Relations Office ñ Tel.: +30 210 8203216 - 218 ñ Fax: +30 210 8214081 ñ http://www.carreer.aueb.gr University Liaison Office ñ Tel. & Fax: +30 210 8203725 ñ http://www.liaison.aueb.gr 2009 ATHENS UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS (AUEB) Research Laboratories A Bridge to Partnership in Research 2009 RECTOR & VICE-RECTORS Gregory P. Prastacos Rector Ioannis Katsoulakos Vice - Rector of Academic Affairs and Personnel Ioannis Halikias Vice - Rector of Economic Affairs Contents Message from the Rector of Athens University of Economics and Business . 5 An Overall View of the Research Areas . 6 1. Department of Economics . 16 1.1. Research in the Department of Economics . 17 1.2. Laboratory of Econometrics . 18 1.3. Laboratory of Economic Policy - EMOP . 20 2. Department of International and European Economic Studies . 22 2.1. Research in the Department of International and European Economic Studies . 23 2.2. Laboratory of European Affairs - EUROLAB . 24 3. Department of Business Administration . 28 3.1. Research in the Department of Business Administration . 29 3.2.