Beloved and Julia Kristeva's the Semiotic and the Symbolic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Statements Summary

3Q 2019 Earnings Release Studio Dragon November 7, 2019 Disclaimer This financial information in this document are consolidated earnings results based on K-IFRS. This document is provided for the convenience of investors only, before the external audit on our 3Q 2019 financial results is completed. The audit outcomes may cause some parts of this document to change. In addition, this document contains “forward-looking statements” – that is, statements related to future, not past, events. In this context, “forward-looking statements” often address our expected future business and financial performance, and often contain words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “seeks” or “will”. Our actual results to be materially different from those expressed in this document due to uncertainties. 3Q 2019 Earnings Release TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 3Q 2019 Highlights 2 3Q 2019 Operating Performance º Programing º Distribution º Cost 3 Growth Strategies Appendix We Create New Culture 1 3Q 2019 Highlights <Arthdal Chronicles> <Hotel Del Luna> <Miss Lee> <Watcher> <Mr. Temporary> <The Running Mates> <Love Alarm> (1) Programming Distribution Production Revenue Revenue Revenue Trend W131.2bn w60.8bn w60.0bn 13titles (YoY +6.0%) (YoY +24.4%) (YoY -5.4%) (YoY +5 titles) Note (1) Each quarter includes all titles in progress - 4 - We Create New Culture 12 3Q 2019 Operating Performance Summary 3Q19 Revenue (+6.0% YoY) – Hit a record high, driven by diversified business, premium IP, and expanded lineups OP (-49.2% YoY) – Maintained stable fundamentals amid last year’s high-base <Mr. Sunshine> and BEP of <Arthdal Chronices> 4Q19 Aim to reinforce influence via titles incl. -

Studio Dragon (253450) Update Fundamental S to Improve in 2020

2019. 10. 31 Company Studio Dragon (253450) Update Fundamental s to improve in 2020 ● The business environment in Korea and overseas is moving favorably for the Minha Choi media industry—eg , OTT platforms are launching around the world, a number of Analyst Korean players are engaging in M&A activity, and terrestrial broadcasters are [email protected] investing more heavily in tent-pole content. These developments should lead to 822 2020 7798 more demand for quality content, which bodes well for content producers in 2020. Kwak Hoin ● Studio Dragon should enjoy greater earnings stability by producing multi-season Research Associate original content for OTT services. It may produce content for both Netflix and new [email protected] global players. Terrestrial broadcasters are also eager to secure quality content. 822 2020 7763 ● Capitalizing on its popular intellectual property and production prowess, the firm has been expanding into new business areas and should see solid top- and bottom-line growth next year. We raise our 12-month target price to KRW88,000. WHAT’S THE STORY? Poised to benefit from sea change in media market: The business environment has been changing quickly at home and abroad. Several global giants are preparing to launch OTT platforms from November, and, in response, Korean OTT service providers are teaming up to boost their competitiveness. Struggling from low viewership ratings, the country’s three terrestrial broadcasters have altered programming lineups and in AT A GLANCE September launched OTT platform Wavve in partnership with SK Telecom—the latter a move that may lead to greater investment in tent-pole dramas. -

The Story of Astronomy

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 42 - Spring 1998 © 1998, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. The Story of Astronomy Mindy Kalchman University of Toronto Lorne Brown Storyteller It was dark. The night sky hung clear over the tiny city in the valley; the stars awesome in their brilliance. A small group of men stood on the top of the hill, looking across the city and the valley to another hill on the other side, some fifteen kilometers away. There, a similar group had assembled, their lights flickering in the distance. "We're ready," said the leader of the first group, a bearded man with intense eyes. "Check your lantern." What was happening? Was this a covert military operation? A band of thieves and robbers plotting plunder? Actually, it was a scientific experiment. The leader was the great Galileo himself, who would later be denounced for claiming that the Earth revolves around the Sun. The experiment was simplicity itself: a lantern would be uncovered on one hill. Fifteen kilometers away, a second lantern would be uncovered, shining back to the first. Light would have thus traveled thirty kilometers, twice across the valley where the Italian city of Florence nestled. By timing how long it took the light to travel this distance, Galileo could calculate the speed of light. He was going to catch the ghost of the universe! Oral traditions have since time immemorial satisfied generations of children and adults with stories of wonder, fantasy, truth, and mystery. Stories are irreplaceable stimulants for the imagination and an often endless source of entertainment. -

Bay Colt; Ghostzapper

Hip No. Consigned by De Meric Sales, Agent 1 Bay Filly Harlan . Storm Cat Harlan’s Holiday . {Country Romance {Christmas in Aiken . Affirmed Bay Filly . {Dowager February 5, 2013 Tiznow . Cee’s Tizzy {Favoritism . {Cee’s Song (2009) {Chaste . Cozzene {Purity By HARLAN’S HOLIDAY (1999), [G1] $3,632,664. Sire of 9 crops, 56 black type wnrs, $45,751,850, 3 champions, including Shanghai Bobby ($1,857,- 000, Breeders’ Cup Juv. [G1], etc.) and Into Mischief [G1] ($597,080), Majesticperfection [G1], Pretty Girl [G1] (to 3, 2014), Willcox Inn [G2] ($1,015,543), Mendip [G2] ($895,961), Summer Applause ($814,906). 1st dam FAVORITISM, by Tiznow. Unraced. This is her first foal. 2nd dam Chaste, by Cozzene. 4 wins at 4 and 5, $193,952, 3rd Ballston Spa Bree- ders’ Cup H. [G3]. Sister to Call an Audible. Dam of-- Golubushka. Winner at 3, 9,500 euro in France. Total: $12,751. 3rd dam PURITY, by Fappiano. Winner at 3 and 4, $35,335. Dam of 8 winners, incl.-- Chaste. Black type-placed winner, see above. Call an Audible. 3 wins at 3 and 4, $147,453, 3rd Molly Pitcher Breeders’ Cup H. [G2] (MTH, $33,000). Producer. Mexicali Rose. Winner at 2, $24,240. Dam of 6 winners, including-- Baileys Beach. 8 wins, 2 to 5, $177,515, 3rd Maryland Juvenile Cham- pionship S.-R (LRL, $5,500). 4th dam DAME MYSTERIEUSE, by Bold Forbes. 10 wins in 19 starts at 2 and 3, $346,245, Black-Eyed Susan S.-G2, Bonnie Miss S., Holly S., Treetop S., Forward Gal S., Old Hat S., Mademoiselle S., 2nd Acorn S.-G1, Spec- tacular Bid S., 3rd Ashland S.-G2. -

Wormwood Review

OH WORMIE, YOU'VE TURNED SEVENTEEN... The Wormwood ReviewVolume 5,Number 1IssueSeventeenEditor: MarvinMalone ArtEditor: A.SypherGuest editor,this issue:Allen DeLoachNew YorkRepresentative: HaroldBriggs1965, Wormwood ReviewPress The poets and poems in this anthology are repre sentative of the diverse activity reverberating at the Cafe Le Metro on New York's Lower East Side. Being a center of poetry, rather than a school, Le Metro nur tures the most vital facet of the creative arts: the right and the opportunity to present the created without any form of censorship or pre-judgment. Le Metro not only has the importance of having completely open and permissive readings, but presents, one night a week, a feature reader. Each of the feature readers has either previously obtained recognition in the field of writing, or has shown definite, noticeable growth in that di rection. Since the first of these readings in February of 1963, a random choice of writers that have made an appearance is Gilbert Sorrentino, Joel Oppenheimer, Diane diPrima, Gregory Corso, Denise Levertov, John Weiners, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, LeRoi Jones, Brion Gyson, William Burroughs, etc. The list could continue, and then be added to a similar list of prominent poets who frequently participate in the weekly open readings. However, it is not the elite who profit through the Cafe Le Metro movement. It is the neophytes, shaping their thoughts and molding their voices, who profit mainly through the - availability of associations with poets, such as alien Ginsberg, who always manage to give the extra minutes asked of them. Let it suffice to say that Le Metro offers to any person on any level what he comes for honestly,pri marily because its patrons have made it that way and because its patrons, would like to keep it that way. -

Semester to Wrap up on Musical Note

Volume 83 Number 12 Northwestern College, Orange City, IA December 10, 2010 Hays granted Exhibit brings competition, appreciation BY KATE WALLIN NW Student Art Exhibit, which event.” experience. We’re trying too hard to prestigious CONTRIBUTING WRITER opened this week in Dordt’s The joint exhibit is a tradition be meaningful and artsy sometimes. As finals week approaches, Campus Center Art Gallery. The 12 years in the making. Every year, Not to imply that art shouldn’t be acceptance the end of the semester brings exhibit, open daily from 8 a.m. to 10 over 50 pieces of student art are serious, but sometimes we have the always-expectant stress and p.m., offers a wide range of pieces submitted for consideration by a to step back a bit and make fun BY KATI HENG overwhelming schedules. Hours from all mediums and boasts a panel of student jurors. A team of of ourselves or we’ll get too self- OPINION EDITOR in the library, sleepless nights and unique atmosphere crafted by three NW jurors reviewed Dordt’s absorbed; therefore, octopus.” Senior Greta Hays has been excessive amounts of caffeinated students for students. submissions, while a group from Drawing pieces from different selected for a prestigious arts courage are reason enough to make Professor Rein Vanderhill said, Dordt selected NW’s contributions mediums, the show includes management internship at the us consider getting away, if only for “The students are totally on their to the show. paintings, drawings, mixed Kennedy Center in Washington, a short while. own when they make the selections “The pieces I entered were the media, printmaking, photography, D.C. -

Watches, the Tion

THE BUDGET. VOL. I. NO. 44. MILBUKIsr, N. J., WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 1886. 3 CENTS A COPY. We-LayEsDown to Sleep. Ah, those happy, happy days! They sobriety for which the country )B xfi*- Wo lay us down to sleep, are gone. Time has stolen them. A markable. It is an influence so prevajt C. H. Roll, And leave to God the rest, liberal reward will be paid for their ing and so potent that only in rare ii" Whether to wake and weep return, and no questions asked. stances is native genius or individuality Or wake no more be best One day I discovered that I had a able to rise above it.—San Francisco Why vex our souls with care? rival. I could not have been more sur- Chronicle. The grave is cool and low; prised and alarmed had I discovered a Have we found life so fair Splitting Ten-Dollar Bills. That we should dread to go? new continent. He was the ugliest boy in the county. When he had reached a A new departure in the matter of COAL, We've kissed love's sweet red lips, ten-year height he had stopped growing counterfeiting money wa3 brought to And left them sweet and red, light in the United States Sub-Treasury The rose the wild bee sips upward, and had then devoted his whole Blooms on when he is dead. time to spreading. They called him in Baltimore a few days ago. A some- "putty keg." They called him that for what worn §10 Government bill was Some faithful friends we've found, But they who love us best short—and thick. -

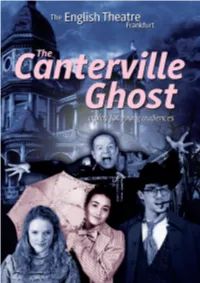

Cantervile Ghost Script.Pdf

The Canterville Ghost a play by Clive Duncan adapted from a short story by Oscar Wilde Cast (in alphabetical order) Sophia Anspach Sophia Cordell-Szczurek Conor Doyle James Moore Creative Team Director Lea Dunbar Set Designer Ivan Aksenov Costume Designer Melanie Schöberl Score Dennis Tjiok The Canterville Ghost Canterville The The Canterville Ghost is a popular short story by Oscar Wilde, widely adapted for the screen and stage. It was the first of Wilde's stories to be published, appearing in the magazine The Court and Society Review in February 1887. The story did not immediately receive much critical attention, and indeed Wilde was not viewed as an important author until the publication, during the 1890s, of his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) and of several well-received plays, including The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). Early critics found Wilde's work unoriginal and derivative. More recently critics have celebrated Wilde's ability to play with the conventions of many genres. In The Canterville Ghost, Wilde draws upon fairy tales, Gothic novels, and stories of Americans abroad to shape his comic ghost story. He creates stereotypical characters that represent both England and the United States, and he presents each of these characters as comical figures, satirizing both the unrefined tastes of Americans and the determination of the British to guard their traditions. Also, he examines the disparity between the public self and the private self, a theme to which Wilde would return again in his later writings. The Canterville Ghost by Clive Duncan The story begins when the Otis family move into Canterville Chase. -

"Scratching Fanny" the Ghost of Cock Lane. a Report By

"SCRATCHING FANNY" THE GHOST OF COCK LANE. A REPORT BY NEW HORIZONS FOUNDATION. Copyright! New Horizons Research Foundation. October 1986. CO COCK-LANE HUMBUG. A Ballad of the time. The Town it long has "been in pain About the phantom in Cock Lane, To find it out they strove in vain, Not one thing they neglected; The«j searched the bed and room compleat to see if there was any cheat. While little Miss that looks so sweet, Was not the least suspected. Then soon the knocking it begun, And then the scratching it would come, Twas pleased to answer any one, And that was done by Knocking. If you was poisoned tell us true, For yes knock once, for No knock two, Then she knocked I tell to you, Which needs must make it shocking. On Friday night as many know, A noble Lord did thither go, The Ghost its knocking would not show Which made the Guest to mutter; They being gone then one was there, Who always called it my dear, Fanny was pleased tis very clear, And then began to flutter. The Ghost some gentlemen did tell, If they would go to Clerkenwell, Into the Vault where she did dwell, That they three knocks should hear. On Monday night away they went, The man accused he was present, But all as death it was silent, The De'il a knock was there Sir. The Gentlemen returned again, And told young missy flat and plain, She was the Agent of Cock Lane, Who knocked and Scratched for Fanny, Twas false each person did agree, Miss begged to go with her daddy, And then went into the Country, To knock and scratch for Fanny. -

Fluvanna Review Is Published Weekly by Valley Legal Ads: the Fluvanna Review Is the Paper of Record for (434) 591-1000 Publishing Corp

FluvannaReview.comFluvannaReview.com October 16-22, 2014 | One Copy Free IL A N S FFluvannaluvanna RREEVVIEWIEW S G G E HHowow HHealthyealthy LY EF N iiss tthehe O T S RRivanna?ivanna? AAquaticquatic LLifeife RRevealseveals tthehe TTruthruth Page 7 NY EN PAGE 20 P R E T A W FFluvanna’sluvanna’s FFirstirst SSameame SexSex MarriageMarriage VDOT Warns on SignsPage 7 Burn Victim Goes Home Page 14 Ghosts Haunt Scottsville Page 24 October 16-22, 2014 • Volume 34, Issue 41 Send your best Fluvanna photo to Quote of the week: Photo of the week carlos@fl uvannareview.com “Over the years the outpouring of love that the FOUNDED IN 1979 BY LEN GARDNER community has given me www.fl uvannareview.com Publisher/Editor: Carlos Santos and my family continues, 434-207-0224 / carlos@fl uvannareview.com and that has helped Advertising/Copy Editor: Jacki Harris 434-207-0222 / sales@fl uvannareview.com sustain me,” Accounts/Classifi ed Ads Manager: Edee Povol 434-207- 0221 / edee@fl uvannareview.com – Angell Husted , Page 11 Advertising Designer: Lisa Hurdle 434-207-0229 / lisa@fl uvannareview.com Editorial Designer: Lynn Stayton-Eurell lynn@fl uvannareview.com IInsidenside Designer: Marilyn Ellinger Staff Writers: Page Gifford, Duncan Nixon, Letters ....................................4 Christina Dimeo Guseman and Tricia Johnson Sports in review ................. 16 Intern: Stephanie Pellicane Calendar ............................. 19 Photographers: O.T. Holen, Lisa Hurdle, Lynn Stayton-Eurell Lunar eclipse seen on Oct. 8 from Columbia Mailing Address: Property transfers ............. 23 Photo by Tricia Johnson P.O. Box 59, Palmyra, VA 22963 Puzzles ................................ 26 Address: Classifi eds........................... 27 2987 Lake Monticello RdRd. -

Millies Dance

Barn I Hip No. Consigned by McKathan Bros., Agent 1 Bay Filly Unbridled’s Song . Unbridled Zensational . {Trolley Song {Joke . Phone Trick Bay Filly . {Tour January 29, 2011 General Meeting . Seattle Slew {Quarterly Report . {Alydar’s Promise (2003) {Fiscal Year . Half a Year {Fiscal Gold By ZENSATIONAL (2006), black type winner of 5 races in 8 starts at 3, $669,300, Bing Crosby S. [G1], Pat O’Brien S. [G1], Triple Bend H. [G1]. Son of Unbridled’s Song [G1], $1,311,800, sire of 96 black type winners, including Midshipman [G1] ($1,584,600, champion), Embur’s Song [G3] ($616,926, champion), Octave [G1]. His first foals are 2-year-olds of 2013. 1st dam Quarterly Report, by General Meeting. Winner at 3, $105,480, 3rd Fleet Treat S.-R (DMR, $13,020). Sister to YEARLY REPORT. Dam of 2 other foals of racing age, one to race-- Donelle (f. by Roman Ruler). Winner in 1 start at 4, 2013, $31,200. Patas de Oro (c. by Roman Ruler). 6 wins, 2 to 4, 2012 in Mexico. 2nd dam FISCAL YEAR, by Half a Year. 3 wins at 2, $95,045, Generous Portion S.-R (DMR, $48,800). Dam of 7 foals to race, all winners, including-- YEARLY REPORT (f. by General Meeting). 6 wins in 10 starts at 2 and 3, $835,900, Delaware Oaks [G2] (DEL, $300,000), Black-Eyed Susan S. [G2] (PIM, $120,000), Santa Ynez S. [G2] (SA, $90,000), Stonerside S. [L] (LS, $90,000)-ntr, Melair S.-R (HOL, $120,000), 2nd California Cup Matron H.-R (SA, $30,000), etc. -

Studio Dragon(253450)

COMPANY UPDATE 2020. 1. 14 Tech Team Minha Choi Studio Dragon (253450) Analyst [email protected] Taking off again 822 2020 7798 We revise up our 12-month target price for Studio Dragon by 15% to KRW108,000 Kwak Hoin • Research Associate given: 1) the likely benefits of the launch of OTT service providers globally; 2) [email protected] mounting expectations about China lifting its ban on Korean content; and 3) 822 2020 7763 improvements in operating results at the firm’s US subsidiary. Although we advise investors to lower their expectations for 4Q operating results, we • believe the Studio Dragon’s fundamentals remain solid. WHAT’S THE STORY ▶ AT A GLANCE Poised to climb: Studio Dragon should make another leap in 2020. We believe Korean Recommend BUY content will be in greater demand this year as OTT platforms have been launching globally Target price KRW108,000 (25.3%) since 4Q19. There are also some signs of improvement in Korea’s relationship with China. Current price KRW86,200 China was formerly a massive consumer of Korean content, but sales to China appear to Market cap KRW2.4t/USD2.1b have been blocked since 4Q16—in tandem with a seeming ban on package tours to Korea. Shares (float) 28,096,370 (30.3%) Three years have passed since the ban was instituted, and China just recently began to 52-week high/low KRW98,300/KRW54,000 allow “incentive travel” again. Later, we also expect China to once again permit concerts Avg daily trading KRW13.8b/ value (60-day) USD11.9m by Korean artists and allow a resumption of media copyright sales.