Physical Activity and Use of Suburban Train Stations: an Exploratory Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 East Ridgewood Avenue

BERGEN RIDGEWOOD COUNTY NJ 9 EAST RIDGEWOOD AVENUE CONCEPTUAL RENDERING SPACE DETAILS LOCATION TAX MAP Between Chestnut and North Broad Streets APPROXIMATE SIZE Ground Floor 8,000 SF SITE STATUS Formerly Capital One Bank TERM Negotiable NEIGHBORS Bareburger, It’s Greek To Me, bluemercury, Papayrus, Roots Steakhouse, PNC Bank, Leon Mexican Cuisine, Town & Country Apothecary, Lucky Brand Jeans, Gap, Starbucks, Park West Tavern,The Office Restaurant, Brasserie Mediterranian, Raymond’s, Alex and Ani, Whole Foods Market, Chico’s and Steel Wheel Tavern COMMENTS Prime retail space in prominent Downtown Ridgewood Strong surrounding retail and affluent demographics Around the corner from Ridgewood NJ Transit train station and from municipal parking Just one block from the site, there are two new luxury residential deveopments approved and planned for construction; 434-unit Chestnust Village and 66-unit Shoppes at Ridgewood Station which will include 8,000 SF of retail space Near Valley Hospital Ridgewood campus; the third busiest hospital in the state of NJ; employing over 4,800 people and serving more than 440,000 per year EAST RIDGEWOOD AVENUE RIDGEWOOD | NJ EAST RIDGEWOODEAST AVENUE RIDGEWOOD AVENUE STREET MAP RIDGEWOOD | NJ King’s Food Market Ridgewood Hot Bagels Tabboule Lisa Thomas Salon PLACE Maggie Moo’s La Bella Pizza H&R Block STREET NORTH MAP SHALL King’s Food Market Corde’s Cleaners MAR COTTAGE M&T Bank Ridgewood Hot Bagels Desired Nails Tabboule Lisa Thomas SalonStop & Shop Blue Water Spa LE PLACE Maggie Moo’s Backyard Living Inc. -

MOVING the NEEDL 2012 NJ TRANSIT ANNUAL REPORT One Trip at a Time TABL of CONTENTS TABL of CONTENTS

MOVING THE NEEDL 2012 NJ TRANSIT ANNUAL REPORT One Trip at a Time TABL OF CONTENTS TABL OF CONTENTS MESSAGES ON-TIME PERFORMANCE Message from On-time Performance 02 the Chairman 26 By Mode Message from On-time Performance 04 the Executive Director 28 Rail Methodology The Year in Review On-time Performance 06 30 Light Rail Methodology On-time Performance FY2012 HIGHLIGHTS 32 Bus Methodology 08 Overview of Scorecard Improving the BOARD, COMMITTEES 10 Customer Experience & MANAGEMENT TEAM 16 Safety & Security 34 Board of Directors 18 Financial Performance 36 Advisory Committees Corporate Executive Management 20 Accountability 37 Team Employee FY2012 Financial 24 Excellence 39 Report COVER PHOTO: Boilermaker IAN EASTWICK 2 NJ TRANSIT 2012 ANNUAL REPORT A MESSAG FROM THE CHAIRMAN NJ TRANSIT 2012 ANNUAL REPORT 3 Each workday, NJ TRANSIT provides nearly one agencies, I convened the Railroad Crossings Leadership million customer trips through the system’s buses, Oversight Committee to take a fresh look at ways to trains, light rail lines and Access Link routes, providing reduce accidental deaths along New Jersey’s rail network. a vital link to employment, education, health care Through an approach called “E-cubed” for engineering, and recreational opportunities. At the beginning of enforcement and education, we continue to ramp up the fiscal year, NJ TRANSIT set course to be the best safety across the NJ TRANSIT system through tactics that public transportation system in the nation through include deployment of new dynamic message signs at Scorecard, the agency’s innovative new performance key locations, testing of “gate skirts” to provide a second management system. -

Volume 8, No 3, 2005

Public JOURNAL OF Transportation Volume 8, No. 3, 2005 ISSN 1077-291X TheJournal of Public Transportation is published quarterly by National Center for Transit Research Center for Urban Transportation Research University of South Florida • College of Engineering 4202 East Fowler Avenue, CUT100 Tampa, Florida 33620-5375 Phone: 813•974•3120 Fax: 813•974•5168 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nctr.usf.edu/journal © 2005 Center for Urban Transportation Research Volume 8, No. 3, 2005 ISSN 1077-291X CONTENTS Paying for Transit in an Era of Federal Policy Change Jeffrey Brown ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Evaluation Analysis on an Integrated Fare Initiative in Beijing Xumei Chen, Guoxin Lin, Lei Yu ........................................................................................................33 Development of Duration Models to Determine Rolling Stock Fleet Size Christopher R. Cherry ............................................................................................................................57 Utah Transit Authority’s Connection Protection System: Perceptions of Riders and Operators Chris Cluett, Jeffrey H. Jenq, Mitsuru Saito ..................................................................................73 Physical Activity and Use of Suburban Train Stations: An Exploratory Analysis Michael Greenberg, John Renne, Robert Lane, Jeffrey Zupan ............................................89 Violence, Harassment, -

Revised TRANSIT

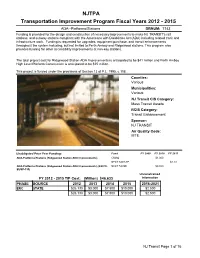

NJTPA Transportation Improvement Program Fiscal Years 2012 - 2015 ADA--Platforms/Stations DBNUM: T143 Funding is provided for the design and construction of necessary improvements to make NJ TRANSIT's rail stations, and subway stations compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) including related track and infrastructure work. Funding is requested for upgrades, equipment purchase, and transit enhancements throughout the system including, but not limited to Perth Amboy and Ridgewood stations. This program also provides funding for other accessibility improvements at non-key stations. The total project cost for Ridgewood Station ADA Improvements is anticipated to be $41 million and Perth Amboy High Level Platform Construction is anticipated to be $25 million. This project is funded under the provisions of Section 13 of P.L. 1995, c.108. Counties: Various Municipalities: Various NJ Transit CIS Category: Mass Transit Assets RCIS Category: Transit Enhancement Sponsor: NJ TRANSIT Air Quality Code: MT8 Unobligated Prior Year Funding: FundFY 2009 FY 2010 FY 2011 ADA-Platforms/Stations (Ridgewood Station ADA Improvements) CMAQ $1.000 SECT 5307-TE $2.13 ADA-Platforms/Stations (Ridgewood Station ADA Improvements) (E2010- SECT 5309D $0.800 BUSP-135) Unconstrained FY 2012 - 2015 TIP Cost: (Million) $46.633 Information PHASE SOURCE 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016-2021 ERC STATE $26.133 $3.000 $7.500 $10.000 $2.500 $26.133 $3.000 $7.500 $10.000 $2.500 NJ Transit Page 1 of 76 NJTPA Transportation Improvement Program Fiscal Years 2012 - 2015 Bridge and Tunnel Rehabilitation DBNUM: T05 This program provides funds for the design, repair, rehabilitation, replacement, painting, inspection of tunnels/bridges, and other work such as movable bridge program, drawbridge power program, and culvert/bridge/tunnel right of way improvements necessary to maintain a state of good repair. -

Eagle River Main Office 11471 Business Blvd Eagle River

POST OFFICE NAME ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE EAGLE RIVER MAIN OFFICE 11471 BUSINESS BLVD EAGLE RIVER AK 99577 HUFFMAN 1221 HUFFMAN PARK DR ANCHORAGE AK 99515 DOWNTOWN STATION 315 BARNETTE ST FAIRBANKS AK 99701 KETCHIKAN MAIN OFFICE 3609 TONGASS AVE KETCHIKAN AK 99901 MIDTOWN STATION 3721 B ST ANCHORAGE AK 99503 WASILLA MAIN OFFICE 401 N MAIN ST WASILLA AK 99654 ANCHORAGE MAIN OFFICE 4141 POSTMARK DR ANCHORAGE AK 99530 KODIAK MAIN OFFICE 419 LOWER MILL BAY RD KODIAK AK 99615 PALMER MAIN OFFICE 500 S COBB ST PALMER AK 99645 COLLEGE BRANCH 755 FAIRBANKS ST FAIRBANKS AK 99709 MENDENHALL STATION 9491 VINTAGE BLVD JUNEAU AK 99801 SYLACAUGA MAIN OFFICE 1 S BROADWAY AVE SYLACAUGA AL 35150 SCOTTSBORO POST OFFICE 101 S MARKET ST SCOTTSBORO AL 35768 ANNISTON MAIN OFFICE 1101 QUINTARD AVE ANNISTON AL 36201 TALLADEGA MAIN OFFICE 127 EAST ST N TALLADEGA AL 35160 TROY MAIN OFFICE 1300 S BRUNDIDGE ST TROY AL 36081 PHENIX CITY MAIN OFFICE 1310 9TH AVE PHENIX CITY AL 36867 TUSCALOOSA MAIN OFFICE 1313 22ND AVE TUSCALOOSA AL 35401 CLAYTON MAIN OFFICE 15 S MIDWAY ST CLAYTON AL 36016 HOOVER POST OFFICE 1809 RIVERCHASE DR HOOVER AL 35244 MEADOWBROOK 1900 CORPORATE DR BIRMINGHAM AL 35242 FLORENCE MAIN OFFICE 210 N SEMINARY ST FLORENCE AL 35630 ALBERTVILLE MAIN OFFICE 210 S HAMBRICK ST ALBERTVILLE AL 35950 JASPER POST OFFICE 2101 3RD AVE S JASPER AL 35501 AUBURN MAIN OFFICE 300 OPELIKA RD AUBURN AL 36830 FORT PAYNE POST OFFICE 301 1ST ST E FORT PAYNE AL 35967 ROANOKE POST OFFICE 3078 HIGHWAY 431 ROANOKE AL 36274 BEL AIR STATION 3410 BEL AIR MALL MOBILE AL 36606 -

New Jersey Department of Transportation Fy 2012-2021 Statewide Transportation Improvement Program

NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FY 2012-2021 STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM DVRPC - FY 2012 Authorized Projects (obligation plan funds only - $ millions) PROJECT NAME FUND PHASE PROG AMT MODIFIED AUTH AMT AUTH DATE BALANCE Burlington Route 130, Crystal Lake Dam (DB #02309) NHS DES $0.000 $1.270 $1.270 $0.000 - Route 130, Crystal Lake Dam - 0017(169) $1.270 01/24/2012 South Pemberton Road, CR 530, Phase 1 (DB #D9912) STP-STU CON $0.000 $3.583 $5.069 $-1.486 - South Pemberton Road, CR 530, Phase 1 - 0222(102) $5.069 09/20/2012 Burlington Subtotal $0.000 $4.853 $6.339 $-1.486 1 10/22/2012 NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FY 2012-2021 STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM DVRPC - FY 2012 Authorized Projects (obligation plan funds only - $ millions) PROJECT NAME FUND PHASE PROG AMT MODIFIED AUTH AMT AUTH DATE BALANCE Camden Camden County Bus Purchase (DB #D0601) CMAQ EC $0.100 $0.100 $0.100 $0.000 - Camden County Bus Purchase (flex to NJ Transit) - flex $0.100 08/29/2012 Route 30, Various locations from East of Brand Ave. to East of London NHS CON $3.850 $3.850 $2.902 $0.948 Ave., Pavement (DB #10335) - Route 30, Various locations from East of Brand Ave. to East of London Ave., Pavement - 0016(165) $2.902 11/21/2011 Route 76/676, Bridge Deck Replacements (DB #11326) BRIDGE ROW $0.000 $1.000 $1.203 $-0.203 - Route 76/676, Bridge Deck Replacements (ROW) - 6768(032) $1.203 08/22/2012 Route 130, Brooklawn Circles (DB #99312) NHS DES $0.000 $1.470 $1.427 $0.043 - Route 130, Brooklawn Circles (FD) - 0017(160) -

Financial Statements

moving the needle 2011 NJ TRANSIT Annual Report 3 Message from the Chairman 4 Message from the Executive Director Governor Chris Christie 5 Year in Review 3 4 5 0 8 Scorecard the needle 10 Equipment Update 8 11 11 Passenger Facilities 14 State of Good Repair 16 Safety and Security Technology 14 18 moving moving 18 19 Transit-Oriented Development 20 Additional Revenue Opportunities 20 21 21 Green Initiatives NJ TRANSIT ON-TIME PERFORMANCE 22 By Mode 26 Board of Directors NJ TRANSIT ON-TIME PERFORMANCE 28 Advisory Committees 23 Rail Methodology Executive Management Team NJ TRANSIT ON-TIME PERFORMANCE 29 Light Rail Methodology 24 FY2011 Financial Report (attached) NJ TRANSIT ON-TIME PERFORMANCE 25 Bus Methodology 2 MEssagE FROM The Chairman Under the leadership of Governor Chris Christie, the Board of Directors and Executive Director Jim Weinstein, NJ TRANSIT positioned itself to be a stronger, more financially-stable agency in FY2011. Despite a stalled national and regional economy and skyrocketing fuel costs, the Corporation rose to the challenge by cutting spending, increasing non- farebox revenue and more effectively managing its resources to reduce a reliance on state subsidies. Those actions allowed us to keep fares stable during the fiscal year, something we are committed to doing again in FY2012. NJ TRANSIT remains an integral part of the state’s transportation network, linking New Jersey residents to jobs, health care, education and recreational opportunities. A number of investments paid dividends for customers this year, including the opening of new or rehabilitated stations, more retail options at stations, continued modernization of the rail and bus fleet, and placing new service-specific technology into the hands of customers. -

Moving Nj Forward

MOVING NJ FORWARD NJ TRANSIT 2010 ANNUAL REPORT 1 coNTents 3 Message from the Chairman 16 what’S NexT 4 Message from the Executive Director 18 NJ TRANSIT oN-TIme 5 The yeAR IN RevIew peRFoRmANce by mode 19 Rail Methodology 8 Fy2010 hIGhLIGhTS 20 Light Rail Methodology 10 Equipment Update 21 Bus Methodology 11 Facility Improvements 12 Transit Oriented Development 22 Board of Directors’ Biographies 13 Green Initiatives 24 Advisory Committees 14 State of Good Repair Fy2010 FINANcial report 15 Technology (Attached) 2 message FRom the chAIRmAN A Message from the Chairman A battered global and regional economy presented NJ TRANSIT with many challenges in FY2010, requiring tough decisions. Steady leadership bridged a change in administrations and helped bring clarity and purpose to the choices that we made to cut spending, increase revenue and target limited resources. A careful selection of projects that we advanced during the year created a portfolio of investments that will pay dividends to our customers in the days and years ahead, when economic and ridership growth return. As the fiscal year unfolded, we responded proactively to ridership declines triggered by a sluggish job market and reduced state funding. Austerity measures, including an emergency spending freeze, cuts in executive salaries and other steps, signaled that the corporation understood the need to make sacrifices before it asked customers late in the fiscal year to pay a higher percentage of the actual cost for the transit services they depend on. It is a testament to the professionalism of NJ TRANSIT leadership and its employees that, despite this difficult fiscal environment, they focused on the future and launched or delivered projects that will serve as the foundation for an improved, interconnected and multimodal public transportation network. -

Moving the Needle

You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library moving the needle 2011 NJ TRANSIT Annual Report You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library 3 Message from the Chairman 4 Message from the Executive Director Governor Chris Christie 5 Year in Review 3 4 5 0 8 Scorecard 10 Equipment Update 8 11 11 Passenger Facilities 14 State of Good Repair 16 Safety and Security Technology 14 18 moving the needle moving 18 19 Transit-Oriented Development 20 Additional Revenue Opportunities 20 21 21 Green Initiatives NJ TRANSIT ON-TIME PERFORMANCE 22 By Mode 26 Board of Directors NJ TRANSIT ON-TIME PERFORMANCE 28 Advisory Committees 23 Rail Methodology Executive Management Team NJ TRANSIT ON-TIME PERFORMANCE 29 Light Rail Methodology 24 FY2011 Financial Report (attached) NJ TRANSIT ON-TIME PERFORMANCE 25 Bus Methodology 2 You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library ME SSAGE FROM The Chairman Under the leadership of Governor Chris Christie, the Board of Directors and Executive Director Jim Weinstein, NJ TRANSIT positioned itself to be a stronger, more financially-stable agency in FY2011. Despite a stalled national and regional economy and skyrocketing fuel costs, the Corporation rose to the challenge by cutting spending, increasing non- farebox revenue and more effectively managing its resources to reduce a reliance on state subsidies. Those actions allowed us to keep fares stable during the fiscal year, something we are committed to doing again in FY2012. NJ TRANSIT remains an integral part of the state’s transportation network, linking New Jersey residents to jobs, health care, education and recreational opportunities. -

Nj Transit Fy2011 Year End Report

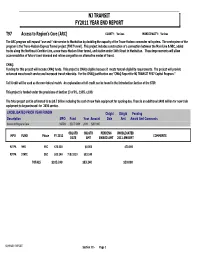

NJ TRANSIT FY2011 YEAR END REPORT T97 Access to Region's Core (ARC) COUNTY: VariousMUNICIPALITY: Various The ARC program will expand "one seat" ride service to Manhattan by doubling the capacity of the Trans-Hudson commuter rail system. The centerpiece of the program is the Trans-Hudson Express Tunnel project (THE Tunnel). This project includes construction of a connection between the Main Line & NEC, added tracks along the Northeast Corridor Line, a new trans-Hudson River tunnel, and station under 34th Street in Manhattan. These improvements will allow accommodation of future travel demand and relieve congestion on alternative modes of travel. CMAQ: Funding for this project will include CMAQ funds. This project is CMAQ eligible because it meets federal eligibility requirements. The project will provide enhanced mass transit service and increased transit ridership. For the CMAQ justification see "CMAQ Report for NJ TRANSIT FY07 Capital Program." Toll Credit will be used as the non-federal match. An explanation of toll credit can be found in the Introduction Section of the STIP. This project is funded under the provisions of Section 13 of P.L. 1995, c.108. The total project cost is estimated to be $8.7 billion including the cost of new train equipment for opening day. There is an additional $400 million for new train equipment to be purchased for 2030 service. UNOBLIGATED PRIOR YEAR FUNDIN Oblgtd Oblgtd Pending DescriptionMPOFund Year Amount Date Amt Award Amt Comments Access to Region's CoreNJTPASECT 5309 2010 $200.000 OBLGTD OBLGTD PENDING UNOBLIGATED MPO FUND Phase FY 2011 COMMENTS DATE AMT AWARD AMT 2011 AMOUNT NJTPANHS ERC $20.000 $0.000 $20.000 NJTPASTATE ERC $83.240 7/8/2010 $83.240 TOTALS $103.240 $83.240 $20.000 SUMMARY REPORT Section III - Page 1 NJ TRANSIT FY2011 YEAR END REPORT T70 ADA--Equipment COUNTY: VariousMUNICIPALITY: Various Funding is provided for the purchase of vans and/or small buses to serve people with disabilities. -

Block 79, Lots 15, 16, 18, 19 and 2 Block 93, Lot 1 New York,New York

PROPOSED FULTON STREET TRANSIT CENTER FULTON,DEY,CHURCH,JOHN,CORTLANDT & WILLIAM STREETS,MAIDEN LANE AND BROADWAY BLOCK 63, LOT 13 BLOCK 79, LOTS 15, 16, 18, 19 AND 2 BLOCK 93, LOT 1 NEW YORK,NEW YORK PHASE IA ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Prepared for: New York City Transit New York, New York Prepared by: The Louis Berger Group, Inc. New York, New York July 2004 PROPOSED FULTON STREET TRANSIT CENTER FULTON,DEY,CHURCH,JOHN,CORTLANDT & WILLIAM STREETS,MAIDEN LANE AND BROADWAY BLOCK 63, LOT 13 BLOCK 79, LOTS 15, 16, 18, 19 AND 2 BLOCK 93, LOT 1 NEW YORK,NEW YORK PHASE IA ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Prepared for: New York City Transit New York, New York Prepared by: The Louis Berger Group, Inc. New York, New York July 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................... ii I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 1 II. PROJECT SETTING ................................................... 5 A. Project Location .................................................... 5 B. Archaeological Area of Potential Effect ................................... 5 C. Existing Utilities/Subsurface Infrastructure ................................ 5 D. Geography and Geology ............................................... 11 E. Plant and Animal Resources ........................................... 14 F. Paleoenvironment ................................................... 14 III. PREHISTORIC CONTEXT ............................................. 16 IV. HISTORIC CONTEXT ................................................ -

United States Department of the Interior •V NATIONAL PARK SERVICE WASHINGTON, D.C

United States Department of the Interior •v NATIONAL PARK SERVICE WASHINGTON, D.C. 20240 IN REPLY REFER TO: JUL | 01984 The Director of the National Park Service is pleased to inform you that the following properties have been entered in the National Register of Historic Places beginning July 1, 1984 and ending July 7, 1984. For further information call (202) 343-9552. STATE .County, Vicinity, Property, A ddress,( D ate Listed) C 0 N NEC TIC U T, Fairfield County, Westport, Bradley-Wheeler House. 25 Avery PL (07/05/84) CONNECTICUT, Litchfield County, Salisbury, Lime Rock Historic District, Roughly White Hollow, Elm, Lime Rock, Norton Hill, and Furnace Rds. (07/05/84) FLORIDA, Broward County, Ft. Lauderdale, Bonnet House. 900 Birch Rd. (07/05/84) G EO R GIA, Clayton County, Lovejoy vicinity, Craw ford-Dorsey House and Cemetery, Freeman and McDonough Rds. (07/05/84) IDAHO, Clearwater County, Weippe, Brownfs Creek CCC Camp Barracks. 105 First St. E. (07/05/84) KANSAS, Wyandotte County, Kansas City, Huron Building, 905 N. 7th St. (07/05/84) KENTUCKY, Garrard County, Lancaster, Methodist Episcopal Church (Lancaster MR A), Stanford St. (07/02/84) ----------------------------------------- MASSACHUSETTS, Essex County, Beverly, Beverly Center Business District. Roughly bounded by Chapman, Central, Brown, Dane, and Essex Sts. (07/05/84) M ASSAC HUSETTS, Hampshire County. Amherst, Strong House. 67 Amity St. (07/05/84) MASSACHUSETTS, Middlesex County, Somerville, Carr, Martin W., SchooL 25 Atherton St. (07/05/84) MASSACHUSETTS, Norfolk County. Quincy, Cranch SchooL 270 WhitwellSt. (07/05/84) MISSISSIPPI, Amite County, Liberty vicinity, Pine wood, S of Liberty off Greensburg Rd.