Minerva, Venus, and Fortune Between Paganism and Christianity in Two Medieval Texts: the Temple of Glas and the Kingis Quair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCCIDENTAL MYTHOLOGY INTRODUCTION 5 Gone, Who Art Gone to the Yonder Shore, Who at the Yonder Shore Tide and Was Followed by the Victories of Rome

Aiso BY JOSEPH CAMPBELL The Masks of God: Oriental Mythology JOSEPH CAMPBELL The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology The Hero with a Thousand Faces A Skcleton Key to Finncgans Wake THE (WITH HENRY MORTON ROBINSON) EDITED BY JOSEPH CAMPBELL MASKS OF 60D: The Portafale Arabian Nights OCCIDENTAL MYTHOLOGY LONDON SECK.ER & WARBURG : 1965 + + + » + * 4444 + * t »4-*-4t* 4+4-44444 »+•» 4- Copyright (c) 1964 by Joseph Campbell All rights reserved CONTENTS First published in England 1965 by Martin Secker & Warburg Limited » + «4+4+444+44 14 Carlisle Street, Soho Square W. l PART ONE: THE..AGE OF THE The Scripture quotations in this publication are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyrighted 1946 and 1952 by the Di- GODDESS Introduction. Myth and Ritual: East vision of Christian Education, National Council of Churches, and used by permission. and West 9 Chapter 1. The Serpent's Bride 9 The author wishes to acknowledge \vith gratitude ihe 17 generous support of his researches by the Bollingen Foundation i. The Mother Goddess Eve n. 31 The Gorgon's Blood 34 m. Ultima Thule Printed in England by IV. Mother Right D. R. Hillman & Son Ltd 42 Frome Chapter 2. The Consort of the Bull 42 45 i. The Mother of God 54 ir. The Two Queens 72 m. The Mother of the Minotaur iv. The Victory of the Sons of Light PART TWO: THE AGE OF HERDES Chapter 3. Gods and Heroes of the Levant: 1500-500 B.C. 95 i. The Book of the Lord The 95 n. Mythological Age The Age 101 m. -

CECA COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES May 17, 2012 PRESENT

CECA COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES May 17, 2012 PRESENT ABSENT Armand Antommaria Jack Gallagher Art Derse Christine Mitchell Bob Baker (Code liaison) Nneka Mokwunye Ken Berkowitz Tia Powell Jeffrey Berger Marty Smith Joseph Carrese Brian Childs Paula Goodman-Crews Ann Heesters Martha Jurchak Kayhan Parsi Kathy Powderly Terry Rosell Wayne Shelton Jeffrey Spike Anita Tarzian (chair) Lucia Wocial Pearls & Pitfalls paper The “HCEC PEARLS AND PITFALLS”: Suggested Do’s And Don’ts for Health Care Ethics Consultants” manuscript has been accepted by JCE. JCE will retain the copyright for the full article, but the Pearls & Pitfalls themselves can be posted on ASBH website and used by others (with appropriate citation). Timing of the publication has not yet been established. Joe mentioned the statement in the current manuscript that readers can provide feedback about the paper on the ASBH website. Kayhan mentioned that ASBH’s website is currently undergoing revision, and will check with Chris Welber at AMC regarding the ability to have visitors post feedback on a specific location of the website. The manuscript will be modified accordingly before publication to match website capacity. Update from Board The Board is asking that CECA submit the Request for Proposals that was previously put on hold pending the Quality Attestation efforts underway. The Board has decided to pursue both activities in parallel. Anita will circulate the current RFP draft to CECA members to identify a process for completing this and submitting to the Board. The Board is developing operating standards for ASBH standing committees, which will impact CECA’s recent discussion about term limits and member rotation. -

INDIGENOUS MUSIC in HEALING RITUALS a Comparative Study of the Twelve Apostles Church in Ghana and Shamanism in Finland

INDIGENOUS MUSIC IN HEALING RITUALS A comparative study of the Twelve Apostles Church in Ghana and Shamanism in Finland Amos Darkwa Asare Master’s Thesis Nordic Master of Global Music Sibelius Academy University of the Arts Helsinki 2015 ii ABSTRACT Thesis Title Number of pages Indigenous Music in Healing Rituals: A Comparative 106 study of the Twelve Apostles Church in Ghana and Shamanism in Finland. Author Semester Amos Darkwa Asare Autumn 2015 Degree programme GLOMAS (Nordic Master of Global Music) Abstract The study describes and analyzes the use of indigenous music in the healing rituals of the syncretic Twelve Apostles Church in Ghana and shamanism in Finland. In dealing with the main question of how indigenous music should be seen as an integral part of the healing processes of two geographically distant cultures, the thesis focuses on the cultural values, meanings and understandings of the participants. The basis of analysis lies beyond Western medical interpretations and extends to music- singing, drumming and dancing in indigenous or local healing rituals agreed upon by a definable set of people. This includes the people’s beliefs, art, customs and norms. Thus, the thesis presents an ethnographic study of indigenous music in healing by comparing how the syncretic Twelve Apostles Church in Ghana and shamanism in Finland approach their healing rituals with music. The main methods employed are participant observations and interviews. The major finding is that indigenous healings are effective with musical phenomena making the ritual music, and music the ritual. Keywords Indigenous music, healing rituals, Twelve Apostles Church, shamanism, ethnographic study, culture iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This master’s thesis would not have been successful without the assistance, support and encouragement from several people. -

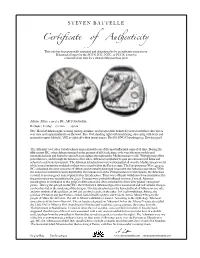

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

The Construction of Pagan Identity in Lithuanian “Pagan Metal” Culture

VYTAUTO DIDŢIOJO UNIVERSITETAS SOCIALINIŲ MOKSLŲ FAKULTETAS SOCIOLOGIJOS KATEDRA Agnė Petrusevičiūtė THE CONSTRUCTION OF PAGAN IDENTITY IN LITHUANIAN “PAGAN METAL” CULTURE Magistro baigiamasis darbas Socialinės antropologijos studijų programa, valstybinis kodas 62605S103 Sociologijos studijų kryptis Vadovas Prof. Ingo W. Schroeder _____ _____ (Moksl. laipsnis, vardas, pavardė) (Parašas) (Data) Apginta _________________________ ______ _____ (Fakulteto/studijų instituto dekanas/direktorius) (Parašas) (Data) Kaunas, 2010 1 Table of contents SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................ 4 SANTRAUKA .................................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 8 I. THEORIZING ―SUBCULTURE‖: LOOKING AT SCIENTIFIC STUDIES .............................. 13 1.1. Overlooking scientific concepts in ―subcultural‖ research ..................................................... 13 1.2. Assumptions about origin of ―subcultures‖ ............................................................................ 15 1.3 Defining identity ...................................................................................................................... 15 1.3.1 Identity and ―subcultures‖ ................................................................................................ -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

A Literary Analysis of Juvenal's Twelfth Satire

MONEY AND MORALITY IN JUVENAL'S TWELFTH SATIRE MORALITY AND MATERIALISM: A LITERARY ANALYSIS OF JUVENAL'S TWELFTH SATIRE By SPENCER JOHN GOUGH, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Spencer Gough, September 2008 MASTER OF ARTS (2008) McMaster University (Classics) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Morality and Materialism: A Literary Analysis of Juvenal's Twelfth Satire AUTHOR: Spencer John Gough, B.A. (Mount Allison University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Paul Murgatroyd NUMBER OF PAGES: v,108 11 ABSTRACT This disseltation examines how Juvenal, in his Twelfth Satire, critiques greed. Caused by human stupidity, a principle theme of the Fourth Book of Satires, greed destroys society by cormpting core values of friendship and religion, and by consuming those characters that Juvenal characterizes negatively throughout the poem. Emphasis is placed on interpreting Juvenal's attitude to and the relationships between the characters of the poem. The mocking portrayal of the narrator's "friend" Catullus, a merchant, characterizes him as being consumed by the same materialism which drives legacy hunters, the targets of the diatribe at the end of the poem. Greed, as exhibited by Catullus and the captatores, spreads vice throughout society by attacking friendship, kinship, religion, and the fundamental values of the state. 1 argue that Juvenal discusses the corruption of his contemporary society as a concrete illustration of the univers al human stupidity outlined in Satire Ten, thus providing a more cohesive reading of Book Four as a whole. 1 also analyse Juvenal's command of intertext and allusion, through the examination of the poet' s playon the poetic storm as a literary motif of the epic genre (Chapter 3), and also by comparing and contrasting the treatment oflegacy-hunting in Satire Twelve and in Horace's Satire 2.5 (Chapter 4). -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Brief Chronicles IV (2012-13) 89 Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna: A Study in Jacobean Literary Form Roger Stritmatter his article investigates the presence of a concealed and previously undetected numerical symbolism in a Stuart-era emblem book, Henry TPeacham’s Minerva Britanna (1611). Although alien to modern conceptions of art, emblem books constitute one of the most widely published and popular genres in early modern book production. Drawing from an eclectic tradition of literary, religious, and iconological traditions, the emblem book combined words and images into complex patterns of signification, often of a markedly didactic character. Popular in all the European vernaculars, it appealed to a wide range of Renaissance readers, from the nearly illiterate (by virtue of its illustrated nature) to the most erudite (by virtue of its reputation for dazzling displays of intellectual and aesthetic virtuosity). By convention the emblem was divided into three parts: superscriptio, pictura, and subscriptio: the superscriptio was the short legend or motto that typically appeared at the top of the page; below it appeared the pictura – the emblem per se – followed by the subscriptio, a longer responsive analysis, usually written in verse, which completed the design. While emblem book scholars still debate the exact relationship between the three parts – and no doubt individual emblem writers themselves sometimes conceived of it in different ways, Deitrich Walter Jöns’ definition constitutes a useful and standard point -

Dream Goddess:Athena

Dream Goddess: Athena Goddess of Wisdom & War Women who embody the Athena archetype are not afraid of their power—in fact they thrive on it. They are achievement oriented, alpha “A- type” personalities. They tend to identify themselves with their work, projects, or creative endeavors, and thus are extremely driven. Contemporary Athena women in Western culture are natural leaders, who usually find themselves either working for themselves or climbing to the top of the corporate ladder. They don’t typically complain about the proverbial “glass ceiling” because they are too busy making strides, working hard, and focusing on the goal they are achieving than on how difficult it is to make it in a “man’s world.” Women ruled by Athena live in a world where they know if they work hard enough, they can create their own destiny. They can be competitive with men and women alike (anyone who stands in the way of her reaching the brass ring she is striving for). The cost of being overly “Athena” can be adrenal burn out, constantly feeling at war, and thus being criticized for being “ruthless” and a “bitch”. Being an extreme Athena archetype can be a lonely road since there’s only room at the top for one person— relationships can be opportunistic, conditional, thus not deep, long-lasting, and satisfying. 1 Athena women’s dreams are filled with wisdom and strategic guidance about how to get ahead in business and become more successful. If you’re not an Athena woman, you definitely want to be on her good side. -

NI 43-101 Technical Report Pilbara Gold Projects Western Australia

NI 43-101 Technical Report Pilbara Gold Projects Western Australia Prepared for: Graphite Energy Corp Prepared by: Xplore Resources Pty Ltd Authors: Matthew Stephens – Senior Consultant Geologist Bryan Bourke – Resource Consultant Geologist Effective Date: 13-Aug-2020 Issue Date: 30-Sep-2020 NI 43-101 Technical Report Pilbara Gold Group Table of Contents 1.0 SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 9 1.1 GEOLOGY ........................................................................................................... 10 1.1.1 BEATONS RIVER PROJECT GEOLOGY ........................................................ 10 1.1.2 CUPRITE EAST AND WEST PROJECT GEOLOGY ...................................... 11 1.1.3 FORTUNA AND TYCHE PROJECT GEOLOGY ............................................ 12 1.1.4 NORTIA PROJECT GEOLOGY ........................................................................ 12 1.2 CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................. 14 1.2.1 BEATONS RIVER PROJECT AREA ................................................................ 14 1.2.2 CUPRITE EAST AND WEST PROJECT AREA............................................... 15 1.2.3 FORTUNA AND TYCHE PROJECT AREA ..................................................... 17 1.2.4 NORTIA PROJECT AREA ................................................................................. 18 1.3 RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................................... -

Temples and Priests of Sol in the City of Rome

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242330197 Temples and Priests of Sol in the City of Rome Article in Mouseion Journal of the Classical Association of Canada · January 2010 DOI: 10.1353/mou.2010.0073 CITATIONS READS 0 550 1 author: S. E. Hijmans University of Alberta 23 PUBLICATIONS 9 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: S. E. Hijmans Retrieved on: 03 November 2016 Temples and Priests of Sol in the city of Rome Summary It was long thought that Sol Invictus was a Syrian sun-god, and that Aurelian imported his cult into Rome after he had vanquished Zenobia and captured Palmyra. This sun-god, it was postulated, differed fundamentally from the old Roman sun-god Sol Indiges, whose cult had long since disappeared from Rome. Scholars thus tended to postulate a hiatus in the first centuries of imperial rule during which there was little or no cult of the sun in Rome. Recent studies, however, have shown that Aurelian’s Sol Invictus was neither new nor foreign, and that the cult of the sun was maintained in Rome without interruption from the city’s earliest history until the demise of Roman religion(s). This continuity of the Roman cult of Sol sheds a new light on the evidence for priests and temples of Sol in Rome. In this article I offer a review of that evidence and what we can infer from it the Roman cult of the sun. A significant portion of the article is devoted to a temple of Sol in Trastevere, hitherto misidentified.