Saydia G Kamal Dissertation Aug 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

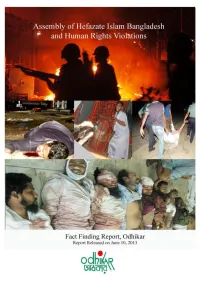

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

Submitted By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by BRAC University Institutional Repository Internship Report On “Internal Investigation Practice: A Study on BRAC” Submitted to: S.M Arifuzzaman Assistant Professor, BBS, BRAC University Submitted by: Fozley Ibnul Lishan ID # 13164070 MBA, Major in Finance Date of Submission: 29th May, 2016 1 Letter of Transmittal May 29, 2016 S.M Arifuzzaman Assistant Professor, BBS, BRAC University Subject: Submission of Internship Report. Dear Sir, I, Fozley Ibnul Lishan, ID: 13164070, Major: Finance, MBA, would like to inform you that I have completed my internship report on “Internal Investigation Practice: A Study on BRAC”. In this regard I have tried my best to complete the work according to your direction. It will be great pleasure for me if kindly accept my report and allow me to complete my degree. Sincerely Yours, Fozley Ibnul Lishan ID: 13164070 MBA, Major: Finance i 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Preparing this report the person helps me, is my coordinator, S.M Arifuzzaman whose cares make me to be served myself for making this report. And the thank goes to my colleagues who always been friendly and cooperative for putting their advices. Friends and People, who added their advices to make this report, obviously are getting worthy of thanks. In preparing this report a considerable amount of thinking and informational inputs from various sources were involved. I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere gratitude to those without their blessing and corporation this report would not have been possible. At the very outset I would like to pay my gratitude to Almighty Allah for the kind blessing to complete the report. -

Global Philanthropy Forum Conference April 18–20 · Washington, Dc

GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE APRIL 18–20 · WASHINGTON, DC 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference This book includes transcripts from the plenary sessions and keynote conversations of the 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GPF, its participants, World Affairs or any of its funders. Prior to publication, the authors were given the opportunity to review their remarks. Some have made minor adjustments. In general, we have sought to preserve the tone of these panels to give the reader a sense of the Conference. The Conference would not have been possible without the support of our partners and members listed below, as well as the dedication of the wonderful team at World Affairs. Special thanks go to the GPF team—Suzy Antounian, Bayanne Alrawi, Laura Beatty, Noelle Germone, Deidre Graham, Elizabeth Haffa, Mary Hanley, Olivia Heffernan, Tori Hirsch, Meghan Kennedy, DJ Latham, Jarrod Sport, Geena St. Andrew, Marla Stein, Carla Thorson and Anna Wirth—for their work and dedication to the GPF, its community and its mission. STRATEGIC PARTNERS Newman’s Own Foundation USAID The David & Lucile Packard The MasterCard Foundation Foundation Anonymous Skoll Foundation The Rockefeller Foundation Skoll Global Threats Fund Margaret A. Cargill Foundation The Walton Family Foundation Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation The World Bank IFC (International Finance SUPPORTING MEMBERS Corporation) The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust MEMBERS Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Anonymous Humanity United Felipe Medina IDB Omidyar Network Maja Kristin Sall Family Foundation MacArthur Foundation Qatar Foundation International Charles Stewart Mott Foundation The Global Philanthropy Forum is a project of World Affairs. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Phd Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

Khan, Adeeba Aziz (2015) Electoral institutions in Bangladesh : a study of conflicts between the formal and the informal. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/23587 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. Electoral Institutions in Bangladesh: A Study of Conflicts Between the Formal and the Informal Adeeba Aziz Khan Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Law 2015 Department of Law SOAS, University of London I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Bangladesh April 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.7 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.3 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 - 4.45 Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 4.1 - 4.4 1972 –1982 4.5 - 4.8 1983 – 1990 4.9 - 4.14 1991 – 1999 4.15 - 4.26 2000 – the present 4.27 - 4.45 5. State Structures 5.1 - 5.51 The constitution 5.1 - 5.3 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 - 5.6 Political System 5.7 - 5.13 Judiciary 5.14 - 5.21 Legal Rights /Detention 5.22 - 5.30 - Death Penalty 5.31 – 5.32 Internal Security 5.33 - 5.34 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.35 – 5.37 Military Service 5.38 Medical Services 5.39 - 5.45 Educational System 5.46 – 5.51 6. Human Rights 6.1- 6.107 6.A Human Rights Issues 6.1 - 6.53 Overview 6.1 - 6.5 Torture 6.6 - 6.7 Politically-motivated Detentions 6.8 - 6.9 Police and Army Accountability 6.10 - 6.13 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.14 – 6.23 Freedom of Religion 6.24 - 6.29 Hindus 6.30 – 6.35 Ahmadis 6.36 – 6.39 Christians 6.40 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.41 Employment Rights 6.42 - 6.47 People Trafficking 6.48 - 6.50 Freedom of Movement 6.51 - 6.52 Authentication of Documents 6.53 6.B Human Rights – Specific Groups 6.54 – 6.85 Ethnic Groups Biharis 6.54 - 6.60 The Tribals of the Chittagong Hill Tracts 6.61 - 6.64 Rohingyas 6.65 – 6.66 Women 6.67 - 6.71 Rape 6.72 - 6.73 Acid Attacks 6.74 Children 6.75 - 6.80 - Child Care Arrangements 6.81 – 6.84 Homosexuals 6.85 Bangladesh April 2004 6.C Human Rights – Other Issues 6.86 – 6.89 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 6.86 - 6.89 Annex A: Chronology of Events Annex B: Political Organisations Annex C: Prominent People Annex D: References to Source Material Bangladesh April 2004 1. -

S-1098-0010-07-00019.Pdf

The Human Development Award A special UNDP Human Development Lifetime Achievement Award is presented to individuals who have demonstrated outstanding commitment during their lifetime to furthering the understanding and progress of human development in a national, regional or global context.This is the first time such a Lifetime Achievement Award has been awarded. Other Human Development Awards include the biennial Mahbub ul Haq Award for Outstanding Contribution to Human Development given to national or world leaders - previously awarded to President Fernando Henrique Cardoso of Brazil in 2002 and founder of Bangladesh's BRAC Fazle Hasan Abed in 2004 - as well as five categories of awards for outstanding National Human Development Reports. Human development puts people and their wellbeing at the centre of development and provides an alternative to the traditional, more narrowly focused, economic growth development paradigm. Human development is about people, about expanding their choices and capabilities to live long, healthy, knowledgeable, and creative lives. Human development embraces equitable economic growth, sustainability, human rights, participation, security, and political freedom. As part of a cohesive UN System, UNDP promotes human development through its development work on the ground in 166 countries worldwide and through the publication of annual Human Development Reports. H.M.the King of Thailand: A Lifetime of Promoting Human Development This first UNDP Human Development Lifetime Achievement Award is given to His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand for his extraordinary contribution to human development on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of his accession to the throne. At his coronation, His Majesty the King uttered the Oath of Accession: "We shall reign with righteousness, for the benefits and happiness of the Siamese people". -

23.11.08 the Daily Star.Pdf (89.05Kb)

Sunday, November 23, 2008 Metropolitan Make human development an enterprise of all humanity Fazle Hasan Abed says at memorial lecture DU Correspondent Make human development an enterprise of all humanity, said Fazle Hasan Abed, founder and chairperson of Brac, at a lecture in the city yesterday. “We must take up every acceptable implement- whether social, legal, scientific, economic or political- to make human development the enterprise of all humanity,” he added. Abed was delivering the Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed Memorial Lecture 2008 on the 'Development as a Right: The Role of Legal Empowerment in the Making of a Just Society' at the National Museum auditorium. It was organised by Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed Memorial Foundation at the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. “When a single member of our neighbourhood lives in poverty and squalor, we are all impoverished,” he said. It is for the governments, organisations and individuals who should practise as a daily act of social justice to make the society a just one, he observed. The Brac founder said in an unequal society where the poor are already disadvantaged, it is important to provide legal safety nets before allowing market forces to operate freely. The present global financial crisis is an example of the unfair economic and social policies at work, he added. Abed said issues like sustainable development, responsible energy, carbon trading or water foot- printing, in the case of Bangladesh, have direct bearing on imminent challenges on several fronts, particularly in food security and climate changes. "It is a sad reality that globally as well as nationally, we have had to wait for such grim realities to shake us out of our self-absorbed comfort zones and make us connect the crucial dots between our rights, needs and responsibilities to our respective societies," he added. -

30 November 2011 Berlin, Dhaka Friends: Wulff

PRESSE REVIEW Official visit of German Federal President in Bangladesh 28 – 30 November 2011 Bangladesh News 24, Bangladesch Thursday, 29 November 2011 Berlin, Dhaka friends: Wulff Dhaka, Nov 29 (bdnews24.com) – Germany is a trusted friend of Bangladesh and there is ample scope of cooperation between the two countries, German president Christian Wulff has said. Speaking at a dinner party hosted by president Zillur Rahman in his honour at Bangabhaban on Tuesday, the German president underlined Bangladesh's valuable contribution to the peacekeeping force. "Bangladesh has been one of the biggest contributors to the peacekeeping force to make the world a better place." Prime minister Sheikh Hasina, speaker Abdul Hamid, deputy speaker Shawkat Ali Khan, ministers and high officials attended the dinner. Wulff said bilateral trade between the two countries is on the rise. On climate change, he said Bangladesh should bring its case before the world more forcefully. http://bdnews24.com/details.php?id=212479&cid=2 [02.12.2011] Bangladesh News 24, Bangladesch Thursday, 29 November 2011 'Bangladesh democracy a role model' Bangladesh can be a role model for democracy in the Arab world, feels German president. "You should not mix religion with power. Tunisia, Libya, Egypt and other countries are now facing the problem," Christian Wulff said at a programme at the Dhaka University. The voter turnout during polls in Bangladesh is also very 'impressive', according to him. The president came to Dhaka on a three-day trip on Monday. SECULAR BANGLADESH He said Bangladesh is a secular state, as minority communities are not pushed to the brink or out of the society here. -

1 Introduction

210 Notes Notes 1Introduction 1 See Taj I. Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, in H. Mutalib and T.I. Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslims and the Modern State, pp. 100–34. 2The Government of Bangladesh, The Constitution of the People’s Repub- lic of Bangladesh, Section 28 (1 & 2), Government Printing Press, Dhaka, 1990, p. 19. 3See Coordinating Council for Human Rights in Bangladesh, (CCHRB) Bangladesh: State of Human Rights, 1992, CCHRB, Dhaka; Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence Against Women, Institute of Democratic Rights, Dhaka, 1991; US Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Prac- tices for 1992, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1993; Rushdie Begum et al., Nari Nirjatan: Sangya O Bishleshon (Bengali), Narigrantha Prabartana, Dhaka, 1992, passim. 4 CCHRB Report, 1993, p. 69. 5 Immigration and Refugee Board (Canada), Report, ‘Women in Bangla- desh’, Human Rights Briefs, Ottawa, 1993, pp. 8–9. 6Ibid, pp. 9–10. 7 The Daily Star, 18 January 1998. 8Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence, pp. 14–15. 9 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 20. 10 Taj Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, p. 117. 11 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 6. 12 Tazeen Mahnaz Murshid, ‘Women, Islam, and the State: Subordination and Resistance’, paper presented at the Bengal Studies Conference (28–30 April 1995), Chicago, pp. 1–2. 13 Ibid, pp. 4–5. 14 U.A.B. Razia Akter Banu, ‘Jamaat-i-Islami in Bangladesh: Challenges and Prospects’, in Hussin Mutalib and Taj Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslim and the Modern State, pp. 86–93. 15 Lynne Brydon and Sylvia Chant, Women in the Third World: Gender Issues in Rural and Urban Areas, p. -

Bangladesh Strategizing Communication in Commercialization of Biotech Crops

Strategizing Communication in Commercialization of Biotech Crops 9 Bangladesh Strategizing Communication in Commercialization of Biotech Crops Khondoker M. Nasiruddin angladesh is on the verge of adopting genetically modified (GM) crops for commercial cultivation and consumption as feed and Bfood. Many laboratories are engaged in tissue culture and molecular characterization of plants, whereas some have started GM research despite shortage of trained manpower, infrastructure, and funding. Nutritionally improved Golden Rice, Bt brinjal, and late blight resistant potato are in contained trial in glasshouses while papaya ringspot virus (PRSV) resistant papaya is under approval process for field trial. The government has taken initiatives to support GM research which include the establishment of a Biotechnology Department in all relevant institutes, and the formation of an apex body referred to as the National Task Force Chapter 9 203 Khondoker M. Nasiruddin he world’s largest delta, Bangladesh BANGLADESH is a very small country in Asia with Tonly 55,598 square miles of land. It is between India which borders almost two-thirds of the territory, and is bounded by Burma to TRY PROFILE TRY the east and south and Nepal to the north. N Despite being small in size, it is home to nearly 130 million people with a population density COU of nearly 2000 per square miles, one of the highest in the world. About 85% live in rural villages and 15% in the urban areas. The country is agricultural where 80% of the people depend on this industry. Fertile alluvial soil of the Ganges- Meghna-Brahmaputra delta coupled with high rainfall and easy cultivation favor agricultural development (Choudhury and Islam, 2002). -

English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh

Advances in Journalism and Communication, 2016, 4, 127-148 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajc ISSN Online: 2328-4935 ISSN Print: 2328-4927 Small Circulation, Big Impact: English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh Jude William Genilo1*, Md. Asiuzzaman1, Md. Mahbubul Haque Osmani2 1Department of Media Studies and Journalism, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2News and Current Affairs, NRB TV, Toronto, Canada How to cite this paper: Genilo, J. W., Abstract Asiuzzaman, Md., & Osmani, Md. M. H. (2016). Small Circulation, Big Impact: Eng- Academic studies on newspapers in Bangladesh revolve round mainly four research lish Language Newspaper Readability in Ban- streams: importance of freedom of press in dynamics of democracy; political econo- gladesh. Advances in Journalism and Com- my of the newspaper industry; newspaper credibility and ethics; and how newspapers munication, 4, 127-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2016.44012 can contribute to development and social change. This paper looks into what can be called as the fifth stream—the readability of newspapers. The main objective is to Received: August 31, 2016 know the content and proportion of news and information appearing in English Accepted: December 27, 2016 Published: December 30, 2016 language newspapers in Bangladesh in terms of story theme, geographic focus, treat- ment, origin, visual presentation, diversity of sources/photos, newspaper structure, Copyright © 2016 by authors and content promotion and listings. Five English-language newspapers were selected as Scientific Research Publishing Inc. per their officially published circulation figure for this research. These were the Daily This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Star, Daily Sun, Dhaka Tribune, Independent and New Age. -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE