Sensitive Space Along the India-Bangladesh Border

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

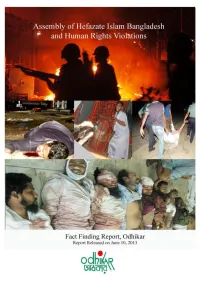

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

BANGLADESH Annual Human Rights Report 2016

BANGLADESH Annual Human Rights Report 2016 1 Cover designed by Odhikar with photos collected from various sources: Left side (from top to bottom): 1. The families of the disappeared at a human chain in front of the National Press Club on the occasion of the International Week of the Disappeared. Photo: Odhikar, 24 May 2016 2. Photo: The daily Jugantor, 1 April 2016, http://ejugantor.com/2016/04/01/index.php (page 18) 3. Protest rally organised at Dhaka University campus protesting the Indian High Commissioner’s visit to the University campus. Photo collected from a facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/SaveSundarbans.SaveBangladesh/videos/713990385405924/ 4. Police on 28 July fired teargas on protesters, who were heading towards the Prime Minister's Office, demanding cancellation of a proposed power plant project near the Sundarbans. Photo: The Daily Star, 29 July 2016, http://www.thedailystar.net/city/cops-attack-rampal-march-1261123 Right side (from top to bottom): 1. Activists of the Democratic Left Front try to break through a police barrier near the National Press Club while protesting the price hike of natural gas. http://epaper.thedailystar.net/index.php?opt=view&page=3&date=2016-12-30 2. Ballot boxes and torn up ballots at Narayanpasha Primary School polling station in Kanakdia of Patuakhali. Photo: Star/Banglar Chokh. http://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/5-killed-violence-1198312 3. On 28 July the National Committee to Protect, Oil, Gas, Natural Resources, Power and Ports marched in a protest rally towards the Prime Minister’s office. Photo: collected from facebook. -

The Burghs of Ayrshire

8 9 The Burghs of Ayrshire Apart from the Stewarts, who flourished in the genealogical as well as material sense, these early families died out quickly, their lands and offices being carried over by heiresses to their husbands' GEOEGE S. PEYDE, M.A., Ph.D. lines. The de Morville possessions came, by way of Alan Professor of Scottish History, Glasgow University FitzEoland of Galloway, to be divided between Balliols, Comyns and de la Zouches ; while the lordship was claimed in thirds by THE HISTORIC BACKGROUND absentees,® the actual lands were in the hands of many small proprietors. The Steward, overlord of Kyle-stewart, was regarded Apart from their purely local interest, the Ayrshire burghs as a Renfrewshire baron. Thus Robert de Bruce, father of the may be studied with profit for their national or " institutional " future king and Earl of Carrick by marriage, has been called the significance, i The general course of burghal development in only Ayrshire noble alive in 1290.' Scotland shows that the terms " royal burgh" (1401) and " burgh-in-barony " (1450) are of late occurrence and represent a form of differentiation that was wholly absent in earlier times. ^ PRBSTWICK Economic privileges—extending even to the grant of trade- monopoly areas—were for long conferred freely and indifferently The oldest burgh in the shire is Prestwick, which is mentioned upon burghs holding from king, bishop, abbot, earl or baron. as burgo meo in Walter FitzAlan's charter, dated 1165-73, to the Discrimination between classes of burghs began to take shape in abbey of Paisley. * It was, therefore, like Renfrew, a baronial the second half of the fourteeth century, after the summoning of burgh, dependent upon the Steward of Scotland ; unlike Renfrew, burgesses to Parliament (in the years 1357-66 or possibly earlier) * however, it did not, on the elevation of the Stewarts to the throne, and the grant to the " free burghs " of special rights in foreign improve in status and it never (to use the later term) became a trade (1364).* Between 1450 and 1560 some 88 charter-grant.? royal burgh. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

The Mineral Industry of India in 2006

2006 Minerals Yearbook INDIA U.S. Department of the Interior March 2008 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF INDIA By Chin S. Kuo India is endowed with a modest variety of mineral resources, 10%. The duty on imported copper ore and concentrates also although deposits of specific resources—barite, bauxite, was reduced to 2% from 5%. The customs duty on steel melting chromite, coal, iron ore, and manganese—were among the scrap was increased to 5% from 0%, however, owing to lower 10 largest in the world. The mineral industry produced many steel prices (Platts, 2006c). industrial minerals and several metals, but a limited number The Indian Government’s Department of Atomic Energy of mineral fuels. Overall, India was a major mineral producer. announced on January 20, 2006, that “titanium ores and The country’s production of mica sheet was ranked first in concentrates (ilmenite, rutile, and leucoxene) shall remain world output; barite, second; chromite, third: iron ore, talc and prescribed substances only till such time [as] the Policy on pyrophyllite, fourth; bauxite, sixth; crude steel and manganese, Exploration of Beach Sand Minerals notified vide Resolution seventh; and aluminum, eighth (U.S. Geological Survey, 2007). Number 8/1(1)97-PSU/1422 dated the 6th of October, 1998 is adopted/revised/modified by the Ministry of Mines or till the 1st Minerals in the National Economy of January 2007, whichever occurs earlier and shall cease to be so thereafter” (WGI Heavy Minerals Inc., 2006a, p. 1). The mining and quarrying sector contributed 2% to the country’s gross domestic product in 2005, which was the Production latest year for which data were available. -

Town of New Scotland Hamlet Development District Zoning March 30, 2017

March 30, 2017 Town of New Scotland Hamlet Development District Zoning March 30, 2017 Prepared with a Community and Transportation Linkage Program grant from the Capital District Transportation Committee New Scotland Hamlet Zoning Sub-Districts Prepared by: 0 March 30, 2017 Disclaimer This report was funded in part through a grant from the Federal Highway Administration (and Federal Transit Administration), U.S. Department of Transportation. The views and opinions of the authors (or agency) expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U. S. Department of Transportation. This report was prepared in cooperation with the Town of New Scotland, the Capital District Transportation Committee, the Capital District Transportation Authority, Albany County and the New York State Department of Transportation. The contents do not the necessarily reflect the official views or policies of these government agencies. The recommendations presented in this report are intended to support the Town of New Scotland’s efforts to implement land use and transportation recommendations identified in the New Scotland Hamlet Master Plan. The zoning language is one of the tools that will help the town realize the vision expressed in the Master Plan. The recommendations do not commit the Town of New Scotland, CDTC, CTDA, NYSDOT, or Albany County to funding any of the improvements identified. All transportation concepts will require further engineering evaluation and review. Environmental Justice Increased attention has been given to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) related to its ability to balance overall mobility benefits of transportation projects against protecting quality of life of low-income and minority residents of a community. -

The Psychological Province of the Reader in Hamlet Ali

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL PROVINCE OF THE READER IN HAMLET ALI SALAMI1 Introduction The baffling diversity of responses to Hamlet, tainted by philosophy, psychology, religion, politics, history and ethics, only conduces to the ever-increasing complications of the play. In Hamlet, the imagination runs wild and travels far beyond the text, to the extent that the reader perceives things that stand not within but utterly without the text. In reading the play, the reader finds in themselves hidden meanings and pent-up feelings and relates them to the play. In the process of reading Hamlet, the reader’s imagination fails to grasp the logic of events. Therefore, instead of relating the events to their world, the reader relates their own world to the text. As a result, the world perceived by the reader is not Hamlet’s but the reader’s. In other words, every reader brings their own world to the play. This study seeks to show how the reader can detach themselves from Hamlet and let their imagination run free. It also shows that the reality achieved by the reader in the course of reading the play is only the reality that dwells in the innermost recesses of their own mind. Hamlet the Character By general consent, Hamlet is one of the most complicated characters in the history of Western literature. With the development of psychoanalysis, Hamlet the character has been widely treated as a real person, rather than one created by a human mind. Even the greatest scholars have taken Hamlet out of the text and analysed and psychoanalysed him as a human personality, albeit with little success as to the discovery of the real motivations of the character. -

AP Human Geography Exam Vocabulary Items

AP Human Geography Exam Unit 2: Population Population density - arithmetic, physiologic Vocabulary Items Distribution The following vocabulary items can be found in your Dot map review book and class handouts. These Major population concentrations - East Asia, South identifications and concepts do not necessarily Asia, Europe, North America, Nile Valley,... constitute all that will be covered on the exam. Megalopolis Population growth - world regions, linear, exponential Doubling time (70 / rate of increase) Unit 1: Nature and Perspectives Population explosion Pattison's Four Traditions - locational, culture- Population structure (composition) - age-sex environment, area-analysis, earth-science pyramids Five Themes - location, human/environmental Demography interaction, region, place, movement Natural increase Absolute/relative location Crude birth/death rate Region - formal, functional, perceptual (vernacular) Total fertility rate Mental map Infant mortality Environmental perception Demographic Transition Model - High Stationary, Components of culture - trait, complex, system, Early Expanding, Late Expanding, Low Stationary region, realm Stationary Population Level (SPL) Culture hearth Population theorists - Malthus, Boserup, Marx (as Cultural landscape well as the Cornucopian theory) Sequent occupance Absolute/relative distance Cultural diffusion Immigration/emigration Independent invention Ernst Ravenstein - "laws" of migration, gravity Expansion diffusion - contagious, hierarchical, model stimulus Push/pull factors - catalysts of -

HRSS Annual Bulletin 2018

Human Rights in Bangladesh Annual Bulletin 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS SUPPORT SOCIETY (HRSS) www.hrssbd.org Annual Human Rights Bulletin Bangladesh Situation 2018 HRSS Any materials published in this Bulletin May be reproduced with acknowledgment of HRSS. Published by Human Rights Support Society D-3, 3rd Floor, Nurjehan Tower 2nd Link Road, Banglamotor Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.hrssbd.org Cover & Graphics [email protected] Published in September 2019 Price: TK 300 US$ 20 ISSN-2413-5445 BOARD of EDITORS Advisor Barrister Shahjada Al Amin Kabir Md. Nur Khan Editor Nazmul Hasan Sub Editor Ijajul Islam Executive Editors Research & Publication Advocacy & Networking Md. Omar Farok Md. Imamul Hossain Monitoring & Documentation Investigation & Fact findings Aziz Aktar Md. Saiful Islam Ast. IT Officer Rizwanul Haq Acknowledgments e are glad to announce that HRSS is going to publish “Annual Human Rights Bulletin 2018”, focusing on Wsignificant human rights violations of Bangladesh. We hope that the contents of this report will help the people understand the overall human rights situation in the country. We further expect that both government and non-government stakeholders working for human rights would be acquainted with the updated human rights conditions and take necessary steps to stop repeated offences. On the other hand, in 2018, the constitutionally guaranteed rights of freedom of assembly and association witnessed a sharp decline by making digital security act-2018. Further, the overall human rights situation significantly deteriorated. Restrictions on the activities of political parties and civil societies, impunity to the excesses of the security forces, extrajudicial killing in the name of anti-drug campaign, enforced disappearance, violence against women, arbitrary arrests and assault on opposition political leaders and activists, intimidation and extortion are considered to be the main reasons for such a catastrophic state of affairs. -

1 Introduction

210 Notes Notes 1Introduction 1 See Taj I. Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, in H. Mutalib and T.I. Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslims and the Modern State, pp. 100–34. 2The Government of Bangladesh, The Constitution of the People’s Repub- lic of Bangladesh, Section 28 (1 & 2), Government Printing Press, Dhaka, 1990, p. 19. 3See Coordinating Council for Human Rights in Bangladesh, (CCHRB) Bangladesh: State of Human Rights, 1992, CCHRB, Dhaka; Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence Against Women, Institute of Democratic Rights, Dhaka, 1991; US Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Prac- tices for 1992, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1993; Rushdie Begum et al., Nari Nirjatan: Sangya O Bishleshon (Bengali), Narigrantha Prabartana, Dhaka, 1992, passim. 4 CCHRB Report, 1993, p. 69. 5 Immigration and Refugee Board (Canada), Report, ‘Women in Bangla- desh’, Human Rights Briefs, Ottawa, 1993, pp. 8–9. 6Ibid, pp. 9–10. 7 The Daily Star, 18 January 1998. 8Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence, pp. 14–15. 9 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 20. 10 Taj Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, p. 117. 11 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 6. 12 Tazeen Mahnaz Murshid, ‘Women, Islam, and the State: Subordination and Resistance’, paper presented at the Bengal Studies Conference (28–30 April 1995), Chicago, pp. 1–2. 13 Ibid, pp. 4–5. 14 U.A.B. Razia Akter Banu, ‘Jamaat-i-Islami in Bangladesh: Challenges and Prospects’, in Hussin Mutalib and Taj Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslim and the Modern State, pp. 86–93. 15 Lynne Brydon and Sylvia Chant, Women in the Third World: Gender Issues in Rural and Urban Areas, p. -

Bangladesh Strategizing Communication in Commercialization of Biotech Crops

Strategizing Communication in Commercialization of Biotech Crops 9 Bangladesh Strategizing Communication in Commercialization of Biotech Crops Khondoker M. Nasiruddin angladesh is on the verge of adopting genetically modified (GM) crops for commercial cultivation and consumption as feed and Bfood. Many laboratories are engaged in tissue culture and molecular characterization of plants, whereas some have started GM research despite shortage of trained manpower, infrastructure, and funding. Nutritionally improved Golden Rice, Bt brinjal, and late blight resistant potato are in contained trial in glasshouses while papaya ringspot virus (PRSV) resistant papaya is under approval process for field trial. The government has taken initiatives to support GM research which include the establishment of a Biotechnology Department in all relevant institutes, and the formation of an apex body referred to as the National Task Force Chapter 9 203 Khondoker M. Nasiruddin he world’s largest delta, Bangladesh BANGLADESH is a very small country in Asia with Tonly 55,598 square miles of land. It is between India which borders almost two-thirds of the territory, and is bounded by Burma to TRY PROFILE TRY the east and south and Nepal to the north. N Despite being small in size, it is home to nearly 130 million people with a population density COU of nearly 2000 per square miles, one of the highest in the world. About 85% live in rural villages and 15% in the urban areas. The country is agricultural where 80% of the people depend on this industry. Fertile alluvial soil of the Ganges- Meghna-Brahmaputra delta coupled with high rainfall and easy cultivation favor agricultural development (Choudhury and Islam, 2002). -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome.