Analysis of the Survey on Social Capital in Cambodia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Delegation

An invitation to experience Cambodia’s transformation through the arts Cultural Delegation 10 days-9 nights Siem Reap . Battambang Phnom Penh January 29 - February 07, 2018 August 06 - August 15, 2018 January 28 - February 06, 2019 An Invitation On behalf of Cambodian Living Arts, I would like to personally invite you on an exclusive journey through the Kingdom of Cambodia. Our Cultural Delegations give you an insight into Cambodia like no other, through a unique blend of tourism and personal encounters with the people who’ve contributed to the country’s cultural re-emergence. With almost 20 years of experience, CLA has grown into one of the leading arts and cultural institutions in Cambodia. What began as a small program supporting four Master Artists has blossomed into a diverse and wide-reaching organization providing opportunities for young artists and arts leaders, supporting arts and culture education in Cambodia, expanding audiences and markets for Cambodian performing arts, and building links with our neighbors in the region. We would love for you to come and experience this transformation through the arts for yourself. Our Cultural Delegation will give you the chance to see the living arts in action and to meet artists, students and partners working to support and develop Cambodia’s rich artistic heritage. Through these intimate encounters you will come to understand the values and aspirations of Cambodian artists, the obstacles they face, and the vital role that culture plays in society here. Come with us and discover the impressive talents of this post-conflict nation and the role that you can play as an agent of change to help develop, sustain and grow the arts here in the Kingdom of Culture. -

Sthapatyakam. the Architecture of Cambodia

STHAPATYAKAM The Architecture of Cambodia ស䮐ាបតាយកម䮘កម䮖ុᾶ The “Stha Patyakam” magazine team in front of Vann Molyvann’s French Library on the RUPP Campus Supervisor Dr. Tilman Baumgärtel Thanks to Yam Sokly, Heritage Mission, who has Design Supervisor Christine Schmutzler shared general knowledge about architecture in STHAPATYAKAM Editorial Assistant Jenny Nickisch Cambodia, Oun Phalline, Director of National Museum, The Architecture of Cambodia Writers and Editors An Danhsipo, Bo Sakalkitya, Sok Sophal, Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Architecture, Chey Phearon, Chhuon Sophorn, Cheng Bunlong, for an exclusive interview, Chheang Sidath, architect at Dareth Rosaline, Heng Guechly, Heang Sreychea, Ly Chhuong Import & Export Company, Nhem Sonimol, ស䮐ាបតាយកម䮘កម䮖ុᾶ Kun Chenda, Kim Kotara, Koeut Chantrea, Kong Sovan, architect student, who contributed the architecture Leng Len, Lim Meng Y, Muong Vandy, Mer Chanpolydet, books, Chhit Vongseyvisoth, architect student, A Plus Sreng Phearun, Rithy Lomor Pich, Rann Samnang, who contributed the Independence Monument picture, Samreth Meta, Soy Dolla, Sour Piset, Song Kimsour, Stefanie Irmer, director of Khmer Architecture Tours, Sam Chanmaliny, Ung Mengyean, Ven Sakol, Denis Schrey from Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Phnom Department of Media and Communication Vorn Sokhan, Vann Chanvetey, Yar Ror Sartt, Penh for financial support of the printing, to the Royal University of Phnom Penh Yoeun Phary, Nou Uddom. Ministry of Tourism that has contributed the picture of Russian Boulevard, Phnom Penh Illustrator Lim -

Re-Imagining Khmer Identity: Angkor Wat During the People's Republic Of

Re-imagining Khmer Identity: Angkor Wat during the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979-1989) Simon Bailey A Thesis in The Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2018 © Simon Bailey, 2018 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Simon Bailey Entitled: Re-imagining Khmer Identity: Angkor Wat during the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979-1989) and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Chair Professor Barbara Lorenzkowski Examiner Professor. Theresa Ventura Examiner Professor Alison Rowley Supervisor Professor Matthew Penney Approved by Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director 2018 Dean of Faculty ABSTRACT Re-imagining Khmer Identity: Angkor Wat during the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979-1989) Simon Bailey The People’s Republic of Kampuchea period between 1979 and 1989 is often overlooked when scholars work on the history of modern Cambodia. This decade is an academic blind spot sandwiched between the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime and the onset of the United Nations peace process. Utilizing mediums such as popular culture, postage stamps and performance art, this thesis will show how the single most identifiable image of Cambodian culture, Angkor Wat became a cultural binding agent for the government during the 1980s. To prove the centrality of Angkor in the myth-making and nation building mechanisms of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea, primary source material from Cambodia’s archives, along with interviews will form the foundation of this investigation. -

Language and Culture of Cambodia SFS 2080

Language and Culture of Cambodia SFS 2080 Syllabus The School for Field Studies (SFS) Center for Conservation and Development Studies Siem Reap, Cambodia This syllabus may develop or change over time based on local conditions, learning opportunities, and faculty expertise. Course content may vary from semester to semester. www.fieldstudies.org © 2019 The School for Field Studies Fa19 COURSE CONTENT SUBJECT TO CHANGE Please note that this is a copy of a recent syllabus. A final syllabus will be provided to students on the first day of academic programming. SFS programs are different from other travel or study abroad programs. Each iteration of a program is unique and often cannot be implemented exactly as planned for a variety of reasons. There are factors which, although monitored closely, are beyond our control. For example: • Changes in access to or expiration or change in terms of permits to the highly regulated and sensitive environments in which we work; • Changes in social/political conditions or tenuous weather situations/natural disasters may require changes to sites or plans, often with little notice; • Some aspects of programs depend on the current faculty team as well as the goodwill and generosity of individuals, communities, and institutions which lend support. Please be advised that these or other variables may require changes before or during the program. Part of the SFS experience is adapting to changing conditions and overcoming the obstacles that may be present. In other words, the elephants are not always where we want them to be, so be flexible! 2 Course Overview The Language and Culture course contains two distinct but related modules: Cambodian society and culture, and Khmer language. -

The Emergence of Cambodian Women Into the Public

WOMEN WALKING SILENTLY: THE EMERGENCE OF CAMBODIAN WOMEN INTO THE PUBLIC SPHERE A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Joan M. Kraynanski June 2007 WOMEN WALKING SILENTLY: THE EMERGENCE OF CAMBODIAN WOMEN INTO THE PUBLIC SPHERE by JOAN M. KRAYNANSKI has been approved for the Center for International Studies by ________________________________________ Elizabeth Fuller Collins Associate Professor, Classics and World Religions _______________________________________ Drew McDaniel Interim Director, Center for International Studies Abstract Kraynanski, Joan M., M.A., June 2007, Southeast Asian Studies WOMEN WALKING SILENTLY: THE EMERGENCE OF CAMBODIAN WOMEN INTO THE PUBLIC SPHERE (65 pp.) Director of Thesis: Elizabeth Fuller Collins This thesis examines the changing role of Cambodian women as they become engaged in local politics and how the situation of women’s engagement in the public sphere is contributing to a change in Cambodia’s traditional gender regimes. I examine the challenges for and successes of women engaged in local politics in Cambodia through interviews and observation of four elected women commune council members. Cambodian’s political culture, beginning with the post-colonial period up until the present, has been guided by strong centralized leadership, predominantly vested in one individual. The women who entered the political system from the commune council elections of 2002 address a political philosophy of inclusiveness and cooperation. The guiding organizational philosophy of inclusiveness and cooperation is also evident in other women centered organizations that have sprung up in Cambodia since the early 1990s. My research looks at how women’s role in society began to change during the Khmer Rouge years, 1975 to 1979, and has continued to transform, for some a matter of necessity, while for others a matter of choice. -

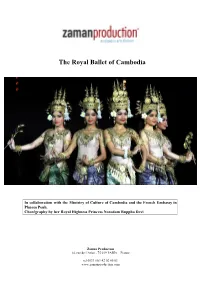

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia In collaboration with the Ministry of Culture of Cambodia and the French Embassy in Phnom Penh. Chorégraphy by her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Zaman Production 14, rue de l’Atlas - 75 019 PARIS – France tel 0033 (0)1 42 02 00 03 www.zamanproduction.com IMMATERIAL HERITAGE UNESCO duration : 1h20 UNESCO : Choreography by Her Royal Highness Princess Norodom Buppha Devi Renowned for its graceful hand gestures and stunning costumes, the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, also known as Khmer Classical Dance, has been closely associated with the Khmer court for over one thousand years. Performances would traditionally accompany royal ceremonies and observances such as coronations, marriages, funerals or Khmer holidays. This art form, which narrowly escaped annihilation in the 1970s, is cherished by many Cambodians. Infused with a sacred and symbolic role, the dance embodies the traditional values of refinement, respect and spirituality. Its repertory perpetuates the legends associated with the origins of the Khmer people. Consequently, Cambodians have long esteemed this tradition as the emblem of Khmer culture. Four distinct character types exist in the classical repertory: Neang the woman, Neayrong the man, Yeak the giant, and Sva the monkey. Each possesses distinctive colours, costumes, makeup and masks.The gestures and poses, mastered by the dancers only after years of intensive training, evoke the gamut of human emotions, from fear and rage to love and joy. An orchestra accompanies the dance, and a female chorus provides a running commentary on the plot, highlighting the emotions mimed by the dancers, who were considered the kings’ messengers to the gods and to the ancestors. -

Hear the Cry of the Earth and the Poor Whakarongo Ki Te Tangi O Papatūānuku Me Te Hunga Pōhara

LENT 2016 TEACHER’S BOOKLET Hear the cry of the earth and the poor Whakarongo ki te tangi o Papatūānuku me te hunga pōhara We need to strengthen the conviction that we are one single human family. Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, #52 Introduction Food Security Climate Change This year’s school resource In September 2015 the United Nations announced its 2030 In his recent encyclical, Laudato Si’, Pope Francis says that the for Lent focuses on the Agenda for Sustainable Development. Among its 17 goals to negative effects of climate change are felt most by those who be achieved by 2030 is ending hunger and ensuring access have made the smallest contribution to it: the poor. experiences and challenges by all people to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year In Cambodia, the effects of climate change are experienced of Cambodians living in round. In order to do this they have a target of doubling the by small farmers who notice that the wet season rainfall has agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale farmers. rural areas. Students will increased and the dry season rainfall has decreased. They This means small food producers will be supported with learn about the rich culture experience long periods of drought and then flash-flooding. In training, financial services, access to markets and fair access the past, flooding has resulted in the destruction of more than and recent sad history of to land. Cambodia, while being half the rice crop of the entire country. This trend looks set to Development and Partnership in Action, Cambodia (DPA) continue unless Cambodia’s farmers can learn to adapt their exposed to social justice and Caritas Aotearoa New Zealand are working with small agricultural methods to the changing weather patterns. -

Society and Culture of Cambodia in the Angkorian Period Under the Influence of Buddhism

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No. 8 (2021), 2420-2423 Research Article Society and Culture of Cambodia in the Angkorian Period under the influence of Buddhism Phra Ratchawimonmolia, Phra Dhammamolee, (Thongyoo) Drb. Phra Khrupanyasudhammanitesc, Phramaha Yuddhapicharn Thongjunrad, Thanarat Sa-ard-iame a,b,e Department of Buddhist Studies, c Department of Political Science, d Department of Public Administration a,b,c,d,e Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Surin Campus, Thailand a [email protected], b [email protected], c [email protected], d [email protected], e [email protected] Article History: Received: 10 January 2021; Revised: 12 February 2021; Accepted: 27 March 2021; Published online: 20 April 2021 Abstract: The purposes of this article were 1) to present the society and culture of Cambodia in the Angkorian period, 2) to discover Buddhism in the Angkorian period, and) to analyze the influence of Buddhism on the society and culture of Cambodia in the Angkorian period. This relies on the primary source of data used in the documentary research. The methodology adopted in the study is of a critical and investigative approach to the analysis of data gathered from documentary sources. The result indicated that: ancient Cambodia inherited civilization from India. The ancient Cambodians, therefore, respected both Brahmin and Buddhism. The Cambodian way of life in the Angkorian era was primarily agricultural occupation, and the monarchy was the ultimate leader. Buddhism has spread in Cambodia after the finishing of the 3rd Buddhist Council. The king accepted Buddhism as the Code of conduct and carried on for a period. -

A Short History of Cambodia.Pdf

Short History of Cambodia 10/3/06 1:57 PM Page i CAMBODIAA SHORT HISTORY OF Short History of Cambodia 10/3/06 1:57 PM Page ii Short History of Asia Series Other books in the series Short History of Bali, Robert Pringle Short History of China and Southeast Asia, Martin Stuart-Fox Short History of Indonesia, Colin Brown Short History of Japan, Curtis Andressen Short History of Laos, Grant Evans Short History of Malaysia, Virginia Matheson Hooker Series Editor Milton Osborne has had an association with the Asian region for over 40 years as an academic, public servant and independent writer. He is the author of many books on Asian topics, including Southeast Asia: An introductory history, first published in 1979 and now in its ninth edition, and The Mekong: Turbulent past, uncertain future, published in 2000. Short History of Cambodia 10/3/06 1:57 PM Page iii A SHORT HISTORY OF CAMBODIA FROM EMPIRE TO SURVIVAL By John Tully Short History of Cambodia 10/3/06 1:57 PM Page iv First published in 2005 by Allen & Unwin Copyright © John Tully 2005 Maps by Ian Faulkner All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. -

Thesis Adviser Recommendation Letter

THESIS ADVISER RECOMMENDATION LETTER This thesis entitled “THE IMPLEMENTATION OF U.S. FOREIGN AID ON CULTURAL HERITAGE PRESERVATION IN CAMBODIA DURING OBAMA’S ADMINISTRATION (2003-2013)” prepared and submitted by Morison Maukar in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor in the Faculty of International Relations, Communication and Law has been reviewed and found to have satisfied the requirements for a thesis fit to be examined. I therefore recommend this thesis for Oral Defense Cikarang, Indonesia, 22 May 2017 Recommended and Acknowledged by, Drs. Teuku Rezasyah, M.A, Ph.D. i APPROVAL SHEET The Panel of Examiners declare that the thesis entitled “The Implementation of U.S. Foreign Aid on Cultural Heritage Preservation in Cambodia During Obama’s Administration (2003-2013)” that was submitted by Morison Maukar majoring in International Relations from the Faculty of International Relations, Communication, and Law was assessed and approved to have passed the Oral Examinations on 31 May 2017. Dr. Endi Haryono Chair – Panel of Examiners Witri Elvianti, S.IP., M.A Examiner Drs. Teuku Rezasyah, M.A, Ph.D. Thesis Adviser ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this thesis, entitled “THE IMPLEMENTATION OF U.S. FOREIGN AID ON CULTURAL HERITAGE PRESERVATION IN CAMBODIA DURING OBAMA’S ADMINISTRATION (2003-2013)” is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, an original piece of work that has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, to another university to obtain a degree. Cikarang, Indonesia , 22 May 2017 Morison Maukar iii ABSTRACT Title: The Implementation of U.S. Foreign Aid on Cultural Heritage Preservation in Cambodia During Obama’s Administration (2003-2013) The issue of cultural heritage looting, and international trade of arts and antiquities are inevitable to be tackled down as the global priority concern. -

Dining Experiences

CULINARY JOURNEYS ‘Bespoke culinary experiences at Park Hyatt Siem Reap’ THE NUM BANH CHOK CULINARY TOUR (CAMBODIAN RICE NOODLE) Interested to learn about Cambodia’s most-loved noodle dish? Join our talented chefs on a meaningful culinary immersion like no other and discover the farm to fork journey of the Num Banh Chok rice noodle. The tour begins with a short trip to the market before heading out to the countryside to visit a Khmer family who still make the noodles in the traditional method – by hand – similar to how it was done in the olden times. A stop at a diner comes next to witness how the dish is served locally as the chef guide explains the intriguing mythical beginning of the dish. The last destination is at a pottery center where guest participation is encouraged. Learn how to make ceramic bowls that traditionally carry the noodle dish and bring home the bowl as a memento of this one of a kind foodie adventure. The trip is concluded with a delectable lunch featuring the Num Banh Chok dish at The Living Room. APPETIZER Num ansom chrouk Stued crispy sticky rice, yellow bean, pork, vegetable salad MAIN COURSE Num bahn chok samlar prahal Khmer noodle, sh curry broth, long bean, cucumber, green papaya yellow pear ower, water lily stems DESSERT Num akor thnout Akor cake, palm fruit, coconut milk, tossed sesame Price: USD 99 per person Duration: Four hours (9:00 AM - 12:00 PM or 2:00 PM - 6:00 PM) 24 hours advance reservation is required Prices are subject to service charge and applicable government taxes. -

Download Document (PDF | 10.56

Main Angkor Wat Temple Complex. (World Factbook) 2 Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance Table of Contents Welcome - Note from the Director 7 About the Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance 8 Acknowledgments 9 Country Disaster Response Handbook Series Overview 11 Executive Summary 12 Country Overview 13 A. Culture 14 B. Demographics 18 Key Population Centers 19 Economics 20 C. Environment 22 Borders 22 Geography 23 Climate 23 Disaster Threat Analysis 27 A. Hazards 28 Natural 28 Man-Made 34 Infectious Diseases 34 B. Endemic Conditions 36 Government 43 Cambodia Disaster Management Reference Handbook | February 2014 3 A. Government Structure for Disaster Management 45 B. Government Capacity and Capability 52 C. Laws, Policies and Plans on Disaster Management 52 D. Cambodian Military Role in Disaster Relief 55 E. Foreign Assistance 58 Infrastructure 61 A. Airports 62 B. Ports 63 C. Inland Waterways 64 D. Land (Roads/Bridges/Rail) 64 E. Hospitals and clinics 67 F. Schools 68 G. Utilities 71 Power 71 Water and Sanitation 72 H. Systemic factors Impacting Infrastructure 73 Building Codes 73 Traditional Homes in Cambodia 74 Health 75 A. Structure 76 B. Surveillance and reporting 78 C. Management of Dead Bodies after Disasters 81 D.Sexual and Reproductive Health in Disasters 81 E. Psychological and Mental Assistance in Disasters 84 Communications 89 A. Communications structures 90 B. Early Warning Systems 90 4 Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance C. Management of Missing Persons 93 Disaster Management Partners in Cambodia 95 A. U.S. Agencies 96 U.S. DoD 97 U.S.