UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Delegation

An invitation to experience Cambodia’s transformation through the arts Cultural Delegation 10 days-9 nights Siem Reap . Battambang Phnom Penh January 29 - February 07, 2018 August 06 - August 15, 2018 January 28 - February 06, 2019 An Invitation On behalf of Cambodian Living Arts, I would like to personally invite you on an exclusive journey through the Kingdom of Cambodia. Our Cultural Delegations give you an insight into Cambodia like no other, through a unique blend of tourism and personal encounters with the people who’ve contributed to the country’s cultural re-emergence. With almost 20 years of experience, CLA has grown into one of the leading arts and cultural institutions in Cambodia. What began as a small program supporting four Master Artists has blossomed into a diverse and wide-reaching organization providing opportunities for young artists and arts leaders, supporting arts and culture education in Cambodia, expanding audiences and markets for Cambodian performing arts, and building links with our neighbors in the region. We would love for you to come and experience this transformation through the arts for yourself. Our Cultural Delegation will give you the chance to see the living arts in action and to meet artists, students and partners working to support and develop Cambodia’s rich artistic heritage. Through these intimate encounters you will come to understand the values and aspirations of Cambodian artists, the obstacles they face, and the vital role that culture plays in society here. Come with us and discover the impressive talents of this post-conflict nation and the role that you can play as an agent of change to help develop, sustain and grow the arts here in the Kingdom of Culture. -

Sthapatyakam. the Architecture of Cambodia

STHAPATYAKAM The Architecture of Cambodia ស䮐ាបតាយកម䮘កម䮖ុᾶ The “Stha Patyakam” magazine team in front of Vann Molyvann’s French Library on the RUPP Campus Supervisor Dr. Tilman Baumgärtel Thanks to Yam Sokly, Heritage Mission, who has Design Supervisor Christine Schmutzler shared general knowledge about architecture in STHAPATYAKAM Editorial Assistant Jenny Nickisch Cambodia, Oun Phalline, Director of National Museum, The Architecture of Cambodia Writers and Editors An Danhsipo, Bo Sakalkitya, Sok Sophal, Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Architecture, Chey Phearon, Chhuon Sophorn, Cheng Bunlong, for an exclusive interview, Chheang Sidath, architect at Dareth Rosaline, Heng Guechly, Heang Sreychea, Ly Chhuong Import & Export Company, Nhem Sonimol, ស䮐ាបតាយកម䮘កម䮖ុᾶ Kun Chenda, Kim Kotara, Koeut Chantrea, Kong Sovan, architect student, who contributed the architecture Leng Len, Lim Meng Y, Muong Vandy, Mer Chanpolydet, books, Chhit Vongseyvisoth, architect student, A Plus Sreng Phearun, Rithy Lomor Pich, Rann Samnang, who contributed the Independence Monument picture, Samreth Meta, Soy Dolla, Sour Piset, Song Kimsour, Stefanie Irmer, director of Khmer Architecture Tours, Sam Chanmaliny, Ung Mengyean, Ven Sakol, Denis Schrey from Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Phnom Department of Media and Communication Vorn Sokhan, Vann Chanvetey, Yar Ror Sartt, Penh for financial support of the printing, to the Royal University of Phnom Penh Yoeun Phary, Nou Uddom. Ministry of Tourism that has contributed the picture of Russian Boulevard, Phnom Penh Illustrator Lim -

Everyday Experiences of Cambodian Genocide Survivors in Hidden

Documentation Center of Cambodia Democratic Kampuchea Regime Survivors and Sites of Violence Savina Sirik Team Leader of the Transitional Justice Program The Khmer Rouge Movement • Khmer Rouge communist movement o 1940s- emerged as struggle against the French Colonialization o 1950- Formed communist-led United Issarak Front or Khmer Issarak • Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party (KPRP) o 1951- formed with support from Vietnamese communists o Lost the 1955 election to Sangkum Reastr Niyum o 1956 Sieu Heng defected to the Prince Sihanouk government The Khmer Rouge Movement (Cont.) • Workers’ Party of Kampuchea o 1960-Secret congress was held, reorganized the party o Tou Samut disappeared, Pol Pot became the party’s leader o 1965 Visit of Pol Pot to Vietname, China and North Korea • Communist Party of Kampuchea o 1966 changed the party name to CPK o 1966-70 headquarter in Rattanakiri The Khmer Rouge regime, officially known as the Democratic Kampuchea (DK), ruled Cambodia from 1975 to 1979. The Evacuation of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975. Source: Roland Neveu Collective cooperatives and massive agricultural and irrigation projects were established throughout the country Democratic Kampuchea in 1976 Source: DK Ministry of Education, 1976. Administrative Divisions & Security System • 6 Zones • 32 Regions • District • Sub-district • Cooperatives • Security system is divided in five levels with S-21 as the top level security center, followed by zonal, regional, district, and sub-district prisons. • 196 prisons • Over 388 killing sites containing almost 20,000 mass graves • Labor sites • 81 local memorials Former Khmer Rouge security centers Physical evidence of violence in the landscapes remains After the Democratic Kampuchea • Introduce to an unmarked site of mass violence and its relationship to survivors • Consider how contemporary lives of survivors are informed by memories of the genocide • Until today, many survivors still live and work in the same villages where they experienced starvation, forced labors, and torture during the DK. -

Aki Ra Founded His Mine Mu- Seum, Which He Uses to Edu- Cate Visitors About the Risks of Unexploded Ordnance with a View to Avoiding Further Acci- Dents

Volume 19 No. 1 / May 2017 NewsleTTer PROJECT: CAMBODIA put the shell in his museum straightaway. Siem Reap, the second larg- est city in Cambodia, is where Aki Ra founded his mine mu- seum, which he uses to edu- cate visitors about the risks of unexploded ordnance with a view to avoiding further acci- dents. He also established and leads Cambodian Self Help Demining (CSHD), a small, highly professional mine clear- ance organisation. If that is not enough, he and his wife also founded an orphanage Photo: CSHD together, which around thirty Cambodia’s eastern provinces in particular contain a lot of mines and there children now call home, some are around 2,400 mines per kilometre on the Thai border. of whom have been injured by mines themselves. Aki Ra – a former child soldier There is a reason why mines and other weaponry are such who removes mines an important topic in Aki Ra’s life. Explosive remnants of war in Cambodia have killed or maimed 65,000 people in the last forty years – more than in almost any other country. World Without Mines is commit- ted to accelerating the clearance of mines in Cambodia. „I was showing a group of tourists around our mine muse- um recently when a man suddenly came running in,” Aki Ra tells us. „He had just seen children playing with an artillery shell only a hundred metres away.” Aki Ra left the visitors where they were and ran to find the children. They were actu- ally standing there with the shell in their hands. -

Part 3. Discussion Chapter 1

Part 3. Discussion Chapter 1. The Ceramics Unearthed from Longvek and Krang Kor Yuni Sato Department of Planning and Coordination, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties 1. Introduction Conventionally, archeological studies of Cambodia focused mainly on the prehistoric times and the Angkor period, and the post-Angkor period were virtually ignored. This “post-Angkor period” points to the approximately 430-year timeframe be- tween the fall of Angkor in 1431 until 1863 when the French colonial rule began. These 430 years had been cloaked in mystery for a long time. In has only been in recent years that first steps in archeological research of the said period was started mainly by the Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties (Nara 2008). Research was conducted at Longvek, the royal capital of the post-Angkor period, and Krang Kor, a site at which burials was discovered, and many artifacts were excavated there. The unearthed artifacts serve an important role in explaining Cambodia during the post-Angkor period. This chapter will look back on the ceramics, which were excavated at both of the sites, and discuss their characteristics and significance. 2. Ceramics Excavated at the Krang Kor Site As explained in Part 1, the archaeological research of the Krang Kor site can be considered an important case, as two burials were discovered in good condition and a large volume of assemblage that are highly likely connected with each other had been excavated. Of imported ceramics, Si Satchanalai celadon, Chinese celadon, and Jingdezhen blue and white porcelain were all given the general dates of mid-15th century to early 16th century (Chart 1). -

Mai Tho Truyen

C n o n p P G o ử n N m C n M ọ uyền --- o0o --- Nguồn www.chuaxaloi.vn Chuyển sang ebook 18-08-2016 Người thực hiện : Nguyễn Ngọc Thảo - [email protected] Tuyết Nhung - [email protected] Dũng Trần - [email protected] Nam Thiên - [email protected] Link Audio Tại Website http://www.phapthihoi.org Mục Lục LỜI NÓI ẦU PHẬ GI O Ử ÔNG NAM CHƢƠNG I - SỰ MỞ RỘNG CỦA PHẬT GIÁO CHƢƠNG II - NGHI VẤN VỀ SUVARNABHUMI LỊCH Ử PHẬ GI O MIẾN IỆN LỜI NÓI ĐẦU THỜI KỲ THỨ NHẤT THỜI KỲ THỨ HAI KẾT LUẬN LỊCH Ử PHẬ GI O NAM DƢƠNG LỜI NÓI ĐẦU CHƢƠNG I - PHẬT GIÁO Ở NAM DƢƠNG TỪ ĐẦU TỚI THẾ KỶ THỨ VIII TÂY LỊCH CHƢƠNG II - PHẬT GIÁO Ở NAM DƢƠNG, TỪ THẾ KỶ THỨ IX TỚI NGÀY NAY CHƢƠNG III - NGHỆ THUẬT VÀ VĂN CHƢƠNG PHẬT GIÁO NAM DƢƠNG KẾT LUẬN LỊCH SỬ PHẬ GI O CAM BỐ CHƢƠNG I - MỘT ÍT TÀI LIỆU LỊCH SỬ CHƢƠNG II - THỜI KỲ DU NHẬP HAY THỜI KỲ FOU-NAN CHƢƠNG III - THỜI KỲ TCHEN LA (CHƠN LẠP) (Thế kỷ VI-IX) LỊCH Ử PHẬ GI O AI LAO CHƢƠNG I - QUỐC GIA VÀ DÂN TỘC LÀO CHƢƠNG II - PHẬT GIÁO DU NHẬP CHƢƠNG III - ẢNH HƢỞNG PHẬT GIÁO TRONG ĐỜI SỐNG DÂN TỘC LÀO, HIỆN TÌNH PHẬT GIÁO LỊCH Ử PHẬ GI O H I LAN CHƢƠNG I - MỘT ÍT LỊCH SỬ CHƢƠNG II - DU NHẬP VÀ CÁC THỜI KỲ TIẾN BỘ CHƢƠNG III - TÌNH HÌNH PHẬT GIÁO HIỆN NAY LỊCH Ử PHẬ GI O CHIÊM THÀNH CHƢƠNG I - MỘT ÍT LỊCH SỬ CHƢƠNG II - VĂN HÓA VÀ TÔN GIÁO LỊCH Ử PHẬ GI O ÍCH LAN CHƢƠNG I - MỘT ÍT LỊCH SỬ CHƢƠNG II - PHẬT GIÁO DU NHẬP TÍCH LAN CHƢƠNG III - PHẬT GIÁO TÍCH LAN TỪ 200 TỚI 20 TRƢỚC CN CHƢƠNG IV - TỪ ĐẦU TÂY LỊCH CHO ĐẾN HIỆN NAY ---o0o--- CH NH RÍ MAI HỌ RUYỀN (1905-1973) ---o0o--- LỜI NÓI ẦU Với mục đích kế thừa tôn chỉ học Phật và phổ biến giáo lý, tri thức đến mọi tầng lớp cư sĩ, Phật tử được hiểu đúng chánh pháp và hành trì lợi lạc. -

Genocide, Ethnocide, Ecocide, with Special Reference to Indigenous Peoples: a Bibliography

Genocide, Ethnocide, Ecocide, with Special Reference to Indigenous Peoples: A Bibliography Robert K. Hitchcock Department of Anthropology and Geography University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE 68588-0368 [email protected] Adalian, Rouben (1991) The Armenian Genocide: Context and Legacy. Social Education 55(2):99-104. Adalian, Rouben (1997) The Armenian Genocide. In Century of Genocide: Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views, Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons and Israel W. Charny eds. Pp. 41-77. New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc. Adams, David Wallace (1995) Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 1875-1928. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. Africa Watch (1989) Zimbabwe, A Break with the Past? Human Rights and Political Unity. New York and Washington, D.C.: Africa Watch Committee. Africa Watch (1990) Somalia: A Government at War With Its Own People. Testimonies about the Killings and the Conflict in the North. New York, New York: Human Rights Watch. African Rights (1995a) Facing Genocide: The Nuba of Sudan. London: African Rights. African Rights (1995b) Rwanda: Death, Despair, and Defiance. London: African Rights. African Rights (1996) Rwanda: Killing the Evidence: Murders, Attacks, Arrests, and Intimidation of Survivors and Witnesses. London: African Rights. Albert, Bruce (1994) Gold Miners and Yanomami Indians in the Brazilian Amazon: The Hashimu Massacre. In Who Pays the Price? The Sociocultural Context of Environmental Crisis, Barbara Rose Johnston, ed. pp. 47-55. Washington D.C. and Covelo, California: Island Press. Allen, B. (1996) Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzogovina and Croatia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. American Anthropological Association (1991) Report of the Special Commission to Investigate the Situation of the Brazilian Yanomami, June, 1991. -

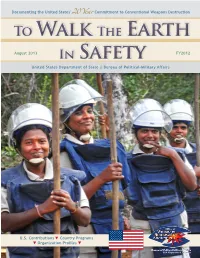

States' Commitment to Conventional Weapons Destruction F United

Documenting the United States’ Commitment to Conventional Weapons Destruction 20Year To Walk The Earth August 2013 In Safety FY2012 United States Department of State | Bureau of Political-Military Affairs U.S. Contributions Country Programs Organization Profiles 180 165 150 135 120 105 90 75 60 45 30 15 0 15 30 45 60 75 90 105 120 135 150 165 180 ON THE COVERS Table of Contents General Information 20 Years of U.S. Commitment to CWD ��������������������������������������������������������������������������4 Conventional Weapons Destruction Overview ����������������������������������������������������������������6 FY2012 Grantees �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 58 List of Common Acronyms . 60 FY2012 Funding Chart �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 61 U.S. Government Interagency Partners 75 Female deminers prepare for work in Sri Lanka. CDC �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 53 Sri Lanka is contaminated by landmines and ex- MANPADS Task Force . 56 plosive remnants of war from over three decades PM/WRA . 13 of armed conflict. From FY2002–FY2012 the U.S. has invested more than $35 million in convention- USAID ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 45 al weapons destruction programs in Sri Lanka. Photo courtesy of Sean Sutton/MAG. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE DTRA . -

S-1 Part I: Immediate Actions for Special Promotion Zone

The Study on Regional Development of the Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville Growth Corridor in The Kingdom of Cambodia PART I: IMMEDIATE ACTIONS FOR SPECIAL PROMOTION ZONE 1. Conclusions and Recommendations for Special Promotion Zone1 1.01 Role of Growth Corridor Area for Economic Development The Growth Corridor area is where the strength of economic development is highest in Cambodia. The area should accommodate new industries in Cambodia to diversify the export commodities and accumulate new technologies. Particularly, the Municipality of Sihanoukville in the hinterland of the Port of Sihanoukville, the only deep seaport of Cambodia, will be a strategically important area for the future of Cambodia, in parallel with the western suburbs of Phnom Penh around the international airport. Specific development strategies and projects discussed in this Study need to be contemplated as a basis for regional development planning of Growth Corridor area. 1.02 Strong Measures Necessary to Diversify Growth Base To prepare for the probable removal of national export quotas and increasing advocacy of regional free trade, Cambodia must diversify its export commodities and export markets. Cambodia needs to diversify the export industries primarily by Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) with necessary technologies and capital, and enhance domestic industries that could provide interactions. Better utilization of local resources other than labor will have to be promoted to increase the value of the resources. Nonetheless, the climate of investment environment of Cambodia is not bright, with unstable domestic conditions and severe international competition, particularly after the accession of China to World Trade Organization (WTO). Cambodia needs to device strong and effective measures to attract FDI by establishing legal base and pilot area with good infrastructure with competitive prices. -

Mine Action and Land Issues in Cambodia

Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining CheminEugène-Rigot 2C PO Box 1300, CH - 1211 Geneva 1, Switzerland T +41 (0)22 730 93 60 [email protected], www.gichd.org Doing no harm? Mine action and land issues in Cambodia Geneva, September 2014 The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), an international expert organisation legally based in Switzerland as a non-profit foundation, works for the elimination of mines, explosive remnants of war and other explosive hazards, such as unsafe munitions stockpiles. The GICHD provides advice and capacity development support, undertakes applied research, disseminates knowledge and best practices and develops standards. In cooperation with its partners, the GICHD's work enables national and local authorities in affected countries to effectively and efficiently plan, coordinate, implement, monitor and evaluate safe mine action programmes, as well as to implement the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, the Convention on Cluster Munitions and other relevant instruments of international law. The GICHD follows the humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality and independence. Special thanks to Natalie Bugalski of Inclusive Development International for her contribution to this report. © Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the GICHD concerning the legal status of any country, territory or armed -

Bombs Over Cambodia

the walrus october 2006 History Bombs Over Cambodia New information reveals that Cambodia was bombed far more heavily during the Vietnam War than previously believed — and that the bombing began not under Richard Nixon, but under Lyndon Johnson story by Taylor Owen and Ben Kiernan mapping by Taylor Owen US Air Force bombers like this B-52, shown releasing its payload over Vietnam, helped make Cambodia one of the most heavily bombed countries in history — perhaps the most heavily bombed. In the fall of 2000, twenty-five years after the end of the war in Indochina, more ordnance on Cambodia than was previously believed: 2,756,941 Bill Clinton became the first US president since Richard Nixon to visit tons’ worth, dropped in 230,516 sorties on 113,716 sites. Just over 10 per- Vietnam. While media coverage of the trip was dominated by talk of cent of this bombing was indiscriminate, with 3,580 of the sites listed as some two thousand US soldiers still classified as missing in action, a having “unknown” targets and another 8,238 sites having no target listed small act of great historical importance went almost unnoticed. As a hu- at all. The database also shows that the bombing began four years earlier manitarian gesture, Clinton released extensive Air Force data on all Amer- than is widely believed — not under Nixon, but under Lyndon Johnson. ican bombings of Indochina between 1964 and 1975. Recorded using a The impact of this bombing, the subject of much debate for the past groundbreaking ibm-designed system, the database provided extensive three decades, is now clearer than ever. -

Cambodia & Vietnam Cycling Adventure

Cambodia & Vietnam Cycling Adventure (extended) Introduction Delve deep into both Cambodia and Vietnam, two very different countries yet both othering gorgeous scenery, vibrant cultures, friendly faces, and delicious cuisines. Take in some of Southeast Asia’s most famous sites such as the extraordinary Angkor Wat and bustling city of Saigon, but also get off the beaten path, get to know the locals, and explore charming village communities. Day 1. Arrive to Siem Reap; Phare Circus Welcome to Cambodia! Upon your arrival to Siem Reap International Airport, our driver will await ready to transfer you to your accommodation. A comfortable centrally-located hotel will put you in good stead for an afternoon of relaxing by the pool or exploring the nearby Old Market area. This evening, you have front row seats at the 8pm show of Phare: The Cambodian Circus. More than just a circus, Phare performers use theatre, music, dance and modern circus arts to tell uniquely Cambodian stories; historical, folk and modern. The young circus artists will astonish you with their energy, emotion, enthusiasm and talent. Accommodation: Riversoul Day 2. Sunrise at Angkor, Explore the Temples 30km cycling As the roosters begin to crow, you will be out at the most important religious monument in Cambodia, watching the sun rise over the triple towers of Angkor Wat. Even in the wet season, this is a magical time to see Angkor. As the crowds thin, take an unforgettable walk through the temple, where the soft light and cool temperatures present Angkor at its best. A short pedal away a delicious breakfast spread awaits.