Death's Jest-Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commencement Schedule

Commencement Schedule Saturday, May 5, 2018 6 Kansas State University Polytechnic Campus Student Life Center, Salina, 10 a.m. Friday, May 11, 2018 9 Graduate School Bramlage Coliseum, 1 p.m. 29 College of Veterinary Medicine McCain Auditorium, 3:30 p.m. Saturday, May 12, 2018 31 College of Arts and Sciences Bramlage Coliseum, 8:30 a.m. 39 College of Architecture, Planning & Design McCain Auditorium, 10 a.m. 41 College of Education Bramlage Coliseum, 11 a.m. 45 College of Business Administration Bramlage Coliseum, 12:30 p.m. 51 College of Agriculture Bramlage Coliseum, 2:30 p.m. 57 College of Human Ecology Bramlage Coliseum, 4:30 p.m. 63 College of Engineering Bramlage Coliseum, 6:30 p.m. 1 CelebratingOur Future Dear Graduates, On behalf of Kansas State University, we extend our sincerest congratulations and best wishes on your graduation. Your degree represents work and commitment on your part and on the part of those who have helped you along your way. Whether it is your family, friends, faculty, staff or fellow students, know that all are proud of your accomplishments. Commencement marks a milestone in your life and sets you on a journey toward a productive and fulfilling career. We hope you use the knowledge and preparation you received at K-State to move forward and make a difference throughout your life, whether in the career field, in the community or in other worthy pursuits. As you embark and progress in your career and life, know that Kansas State University will always encourage you along the way. -

2005 Printable Program

HONORS BACCALAUREATE Honors Baccalaureate and Celebration of Academic Excellence North Carolina State University May 12, 2005 McKimmon Conference and Training Center 2005 Honors Baccalaureate and Celebration of Academic Excellence Acknowledgements The following have contributed significantly to the success of the Honors Baccalaureate and Celebration The Alma Mater of Academic Excellence: University Honors Program Words by Alvin M. Fountain, ‘23 Music by Bonnie F. Norris, ‘23 Office of Professional Development, McKimmon Conference and Training Center NC State Alumni Association Where the winds of Dixie softly blow O’er the fields of Caroline, The Grains of Time Mike Adelman, Zach Barfield, David Brown, Nathaniel Harris, Mack Hedrick, There stands ever cherished NC State, Carson Swanek, James Wallace As thy honored shrine. The SaxPack Casey Byrum, Ryan Guerry, Ashleigh Nagel, Jeremy Smith, and Tony Sprinkle So lift your voices; loudly sing From hill to oceanside! Communication Services NCSU Bookstores Our hearts ever hold you, NC State, In the folds of our love and pride. University Graphics Registration and Records The College Awards Contacts who helped to compile the list of faculty awards: Barbara Kirby and Cheri Hitt (Agriculture & Life Sciences); Jacki Robertson, Carla Skuce, and Michael Pause (Design); Billy O’Steen (Education); Martha Brinson (Engineering); David Shafer and Todd Marcks (Graduate School); Marcella Simmons (Humanities & Social Sciences); Anna Rzewnicki (Management); Robin Hughes (Natural Resources); Winnie Ellis (Physical & Mathematical Sciences); Emily Parker (Textiles); Phyllis Edwards (Veterinary Medicine) This program is prepared for informational purposes only. The appearance of an indvidual’s name does not constitute the University’s acknowledgement, certification, or representation that the individual has fulfilled the requirements for a degree or actually received the indicated designations, awards, or recognitions. -

The Newsletter Number Fourteen 2010

Thomas Lovell Beddoes Society Woodcut of The Dance of Death, from the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493 The Newsletter Number Fourteen 2010 Beddoes to his Critic ‘Tell the students I obsess, Tell them something’s wrong with me. That medicine will help. Impress Them with your sage psychiatry. ‘Tell them that I’m manic, that These phases alternate with gloom. When others stood for Life, I sat. Let these statements fill the room. ‘And if perhaps you find one doubt, Resist your observations, then, Let the final clincher out: Tell them that I favored men. ‘But when you’ve thus disposed of me, And kept yourself from facing death, Do not think we’re finished. See, I await your dying breath.’ Richard Geyer aris 1856 Alphabet of Death ’s , repro P Frame from Hans Holbein Editorial Welcome to Newsletter 14. It’s two years since the last issue – poor form for an annual! – but here’s evidence that something’s still astir on the Ship of Fools. Members will know that following John Beddoes’ resignation as chairman the Society is in a period of transition. The meeting on 13th March resolved that we will continue to pursue our original aim to publicise and promote the work of Thomas Lovell Beddoes. But there are still difficulties to overcome, the most urgent being to appoint a new chairman and secretary. This must be done at the AGM on 25th September (1 pm at The Devereux, 20 Devereux Court, Essex Street, The Strand, London WC2R 3JJ). We hope that by holding the meeting in London as many members as possible will be able to attend and join the discussion: the Society needs you. -

Conservation, Gender, and the Tennessee Valley Authority During the New Deal

ABSTRACT BRADSHAW, LAURA HEPP. Naturalized Citizens: Conservation, Gender, and the Tennessee Valley Authority during the New Deal. (Under the direction of Katherine Mellen Charron and Matthew Morse Booker). Broadly, this thesis is an examination of the conservation movement and the Tennessee Valley Authority from the Progressive Era through the New Deal. The creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority in 1933 had been premised upon earlier efforts to capture the river’s power and harness it to meet social needs. Harnessing hydroelectricity to remedy social and economic conditions in the South required both environmental engineering techniques and social engineering methods. By placing women at the center of the story, both in terms of their activism in bringing a conservation plan in the Tennessee River Valley into fruition, and in terms of the gendered implications of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s power policy, this thesis seeks to reexamine the invisible role that the construction of power politics had on the South, and the nation as a whole. Naturalized Citizens: Conservation, Gender, and the Tennessee Valley Authority during the New Deal by Laura Hepp Bradshaw A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2010 APPROVED BY: _______________________________ ______________________________ Matthew Morse Booker Katherine Mellen Charron Committee Co-Chair Committee Co-Chair ________________________________ David Gilmartin ii DEDICATION To my family, but especially to Karl Hepp Sr., whose own journey inspires me to open new doors, even when they appear locked. Papa, a dal van a lelkemben. -

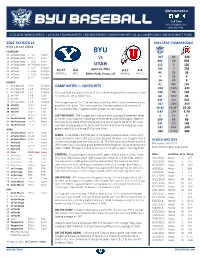

BYU-Utah Game 3 Notes

@BYUBASEBALL BYU BASEBALL Duff Tittle [email protected] 801-372-4401 2 COLLEGE WORLD SERIES | 14 NCAA TOURNAMENTS | 18 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS | 61 ALL-AMERICANS | 118 MLB DRAFT PICKS 2021 SCHEDULE 2021 STAT COMPARISON H 3-5 | A 7-13 | N 0-0 FEBRUARY BYU 20 at Texas State L 4-5 12 pm 20 at Texas State W 9-4 4 pm VS .207 BA .248 22 at Texas State L 6-11 6 pm 894 AB 838 23 at Texas State W 7-6 (10) 4 pm UTAH 113 R 120 24 at Texas L 1-3 7:00 pm April 13, 2021 185 H 208 25 at Texas L 6-12 6:30 pm 10-17 6-6 8-17 4-8 26 at Texas L 1-11 6:30 pm OVERALL WCC Miller Park, Provo, UT OVERALL PAC 12 46 2B 38 27 at Texas W 5-4 3:00 pm 4 3B 4 14 HR 8 MARCH 4 at Oregon St. L 0-1 5:35 pm GAME NOTES — QUICK HITS 91 RBI 105 5 at Oregon St. L 3-5 5:35 pm .314 SLG% .332 6 at Oregon St. L 3-4 1:05 pm BYU and Utah will play the third of four scheduled games this season on April 136 BB 104 11 at Utah L 3-6 3 pm 13, at 6 p.m. MT at Miller Park. 12 HBP 36 12 at Utah L 1-7 3 pm 237 SO 242 16 at Dixie State L 4-5 6:05 pm The Cougars are at 10-17 on the year and 6-6 in West Coast Conference play, 18 at LMU W 5-4 6 pm good for sixth place. -

Literary Disability Studies

Literary Disability Studies Series Editors David Bolt Faculty of Education Liverpool Hope University Liverpool , United Kingdom Elizabeth Donaldson New York Institute of Technology New York , United Kingdom Julia Miele Rodas City University of New York New York , United Kingdom Literary Disability Studies is the fi rst book series dedicated to the exploration of literature and literary topics from a disability studies perspective. Focused on literary content and informed by disability theory, disability research, disability activism, and disability experience, the Palgrave Macmillan series provides a home for a growing body of advanced scholarship exploring the ways in which the literary imagination intersects with historical and contemporary attitudes toward disability. This cutting-edge interdisciplin- ary work will include both monographs and edited collections (as well as focused research that does not fall within traditional monograph length). The series is supported by an editorial board of internationally-recognised literary scholars specialising in disability studies: Michael Bérubé, Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Literature, Pennsylvania State University, USA. G. Thomas Couser, Professor of English Emeritus, Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York, USA. Michael Davidson, University of California Distinguished Professor, University of California, San Diego, USA. Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Professor of Women's Studies and English, Emory University, Atlanta, USA. Cynthia Lewiecki- Wilson, Professor of English Emerita, Miami University, Ohio, USA. Tobin Siebers, V. L. Parrington Collegiate Professor, Professor of English and Art and Design, University of Michigan, USA. For infor- mation about submitting a Literary Disability Studies book proposal, please contact David Bolt ([email protected]), Elizabeth J. Donaldson ([email protected]), and/or Julia Miele Rodas ([email protected]. -

Marat De Sade Studio Arena

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Studio Arena Programs Studio Arena 2-23-1967 Marat De Sade Studio Arena Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/saprograms Recommended Citation Studio Arena, "Marat De Sade" (1967). Studio Arena Programs. 54. http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/saprograms/54 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Studio Arena at Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studio Arena Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDIO THEATRE \/» n (iiilcuk (tnJ I Uh:(i in w < / < v nu n : "MARAT/de SADE" NEXT PRODUCTION LU K A S FO SS OSCAR WILDE's Brilliant Farce Sunday, February 5, 2:30 p.m. Tuesday, February 7, 8:30 p.m. WAI.TKK HKNDI., ( iu i . 'S t C o n d u c t o r .iKssr: i.k v in i:, vinii^i OF BEING ri!i:i)()NI.\ Choir Flos Campi — Vaughn William: Symphony #2 in E. Minor — EARNEST Rachma ninoff Directed by TOM GRUENEWALD Sunday, February 19. 2:30 p.m March 2-25 Tuesday, February 21, S:30 p.iv I.IMvAS KOSS, Conductor ZI\<> FKANCKSCATTl, Violinist Symphony in C — Bizet Violin Concerto — Tschaikovsky March 30-Apnl 22 ANTIGONE Tickets for all performances $4.80, $4.20, $3.60, $2.85 by Jean Anouilh Music Hall (Penn. St. Ent.); 885-5000 and or Denton, Cottier & Daniels, 32 Court St.; (Exc.Wed.). -

Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications Manuscript Version: Author's

Manuscript version: Author’s Accepted Manuscript The version presented in WRAP is the author’s accepted manuscript and may differ from the published version or Version of Record. Persistent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/111594 How to cite: Please refer to published version for the most recent bibliographic citation information. If a published version is known of, the repository item page linked to above, will contain details on accessing it. Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: Please refer to the repository item page, publisher’s statement section, for further information. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected]. warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Stranded wealth: rethinking the politics of oil in an age of abundance Thijs Van de Graaf and Michael Bradshaw* Abstract Even if oil prices have recovered from their plunge in 2014, this article argues that the oil industry is unlikely to return to the status quo ex ante. -

Vanderbilt University Class of 2021 Commencement Program

VANDERBILT COMMENCEMENT 15–16 May 2021 Alma Mater On the city’s western border, reared against the sky, Proudly stands our Alma Mater as the years roll by. Forward! ever be thy watchword, conquer and prevail. Hail to thee, our Alma Mater, Vanderbilt, All Hail! Cherished by thy sons and daughters, memories sweet shall throng ’Round our hearts, O Alma Mater, as we sing our song. Forward! ever be thy watchword, conquer and prevail. Hail to thee, our Alma Mater, Vanderbilt, All Hail! —Robert F. Vaughan, 1907 The medallion on the cover of this program is the Official Seal of Vanderbilt University, adopted by the Board of Trust on May 4, 1875. II Progr am UNDERGRADUATE CEREMONY Procession of stage party starts at 9:00 a.m. Ceremonies on stage start around 9:07 a.m., end about noon. (Guests remain seated throughout the ceremony.) Processional (Banner Bearers, Deans, Founder’s Medalists, Faculty Senate Chair, Alumni Association President, Provost, Chair of Board of Trust, Chancellor) Rondeau Jean-Joseph Mouret Pomp and Circumstance Edward Elgar Trumpet Tune John Stanley Welcome Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Presentation of Emeriti Susan R. Wente, Provost Recognition of Other Academic Guests Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Awarding of Founder’s Medals for First Honors Susan R. Wente, Provost Presentation of Board of Trust Resolution Bruce R. Evans, Board of Trust Chair Farewell Remarks to Graduates Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Conferral of Degrees Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Musical Interlude Kingston Ho, violin, Class of 2023, Blair School of Music Danse Rustique Eugène Ysae Presentation of Graduates Alma Mater Ava Berniece Anderson, Class of 2021, Blair School of Music (Words on page II) Charge to the Graduates Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Finale “Hoe-Down” from Rodeo Aaron Copland SATURDAY 15 MAY 2021 VANDERBILT CAMPUS 1 Contents Te Academic Procession ......................................... -

St. Therese Parish Newsletter

St. Therese Newsletter St. Therese ParishPage 1 Newsletter Volume 15, No. 3 120 West Granby Road Granby, CT 06035 Phone: 860-653-3371 Volume 15 Number 3 Off the Top of My Head by Fr. Tom Ptaszynski Summer 2017 n how many homes have you ized that I actually lived in that house for only ten lived? It is probably unlikely years, until I moved to St. Thomas Seminary. My I that adults live in the same youngest sister has no memory of my presence home they did when they were during her childhood! Over the years, my resi- children. Moving is difficult, espe- dence has changed eight times. And each time, cially whene so many happy grateful for what had been, I looked forward to new memories are associated with the challenges and opportunities. home, apartment or building we are leaving. So, it is with our “new” parish family. We welcome those whose home was St. Bernard’s for many Meeting with the St. Bernard’s cemetery committee years. May we be a family of hospitality, faith, and on May 16, we talked about the sadness associat- love. We will share many celebrations – joy-filled ed with the closing of the building that housed so and sad. But, we will always be the Body of Christ, many celebrations—joy-filled and sad. I reflected making Him present in Tariffville, the Hartlands, on how 62 years to the day, my family moved into and all the Granbys. Remember, “we make the house my mom and dad would call home for Church together.” All are welcome! almost 50 years. -

Oh, Kay Studio Arena

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Studio Arena Programs Studio Arena 4-30-1967 Oh, Kay Studio Arena Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/saprograms Recommended Citation Studio Arena, "Oh, Kay" (1967). Studio Arena Programs. 56. http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/saprograms/56 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Studio Arena at Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studio Arena Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDIO i H E A T R E THEATRE MAGAZINE APR. 30-MAY 6, 1967 GEORGE GERSHWIN’S MUSICAL COMEDY OF THE 192-Os T H H BUFFALO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA L U K A S F O S S Conductor - Music Director presents Bulo Philharmonic Cdiiccrt Goers save u.-i'i percent by subscribing now I'.ijsiiluen cono-rt series Go full or half series Co JSundiiVS or Tin-sdays It is almost like getting the extra concert as a bonus Orders must be in by May 33 It’s a look, a style, Ticket information call a frame of mind. 885-5000 It’s color, and quality, Full series is 3 8 concerts and freedom to try $58.00 $50.00 $42.00 §32.00 something new. A Series is 9 concerts It's an exciting new shop 13 Series is !l concerts in Am erica’s most beautiful s::u.7li *32.25 $27.50 *21.75 new fashion store. -

Asia's Uncertain Lng Future

the national bureau of asian research nbr special report #44 | november 2013 asia’s uncertain lng future By Michael Bradshaw, Mikkal E. Herberg, Amy Myers Jaffe, Damien Ma, and Nikos Tsafos ++ cover 2 The NBR Special Report provides access to current research on special topics conducted by the world’s leading experts in Asian affairs. The views expressed in these reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of other NBR research associates or institutions that support NBR. The National Bureau of Asian Research is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research institution dedicated to informing and strengthening policy. NBR conducts advanced independent research on strategic, political, economic, globalization, health, and energy issues affecting U.S. relations with Asia. Drawing upon an extensive network of the world’s leading specialists and leveraging the latest technology, NBR bridges the academic, business, and policy arenas. The institution disseminates its research through briefings, publications, conferences, Congressional testimony, and email forums, and by collaborating with leading institutions worldwide. NBR also provides exceptional internship opportunities to graduate and undergraduate students for the purpose of attracting and training the next generation of Asia specialists. NBR was started in 1989 with a major grant from the Henry M. Jackson Foundation. Funding for NBR’s research and publications comes from foundations, corporations, individuals, the U.S. government, and from NBR itself. NBR does not conduct proprietary or classified research. The organization undertakes contract work for government and private-sector organizations only when NBR can maintain the right to publish findings from such work. To download issues of the NBR Special Report, please visit the NBR website http://www.nbr.org.