Master and Apprentice Reuniting Thinking with Doing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Diets, Changing Minds: How Food Affects Mental Well Being and Behaviour Acknowledgements

Changing Diets, Changing Minds: how food affects mental well being and behaviour Acknowledgements This report was written by Courtney Van de Weyer, and edited by Jeanette Longfield from Sustain, Iain Ryrie and Deborah Cornah from the Mental Health Foundation* and Kath Dalmeny from the Food Commission. We would like to thank the following for their assistance throughout the production of this report, from its conception to its review: Matthew Adams (Good Gardeners Association), Nigel Baker (National Union of Teachers), Michelle Berridale-Johnson (Foods Matter), Sally Bunday (Hyperactive Children's Support Group), Martin Caraher (Centre for Food Policy, City University), Michael Crawford (Institute of Brain Chemistry and Human Nutrition, London Metropolitan University), Helen Crawley (Caroline Walker Trust), Amanda Geary (Food and Mood), Bernard Gesch (Natural Justice), Maddy Halliday (formerly of the Mental Health Foundation), Joseph Hibbeln (National Institutes of Health, USA), Malcolm Hooper (Autism Research Unit, University of Sunderland), Tim Lang (Centre for Food Policy, City University), Tracey Maher (Young Minds Magazine), Erik Millstone (Social Policy Research Unit, University of Sussex), Kate Neil (Centre for Nutrition Education), Malcolm Peet (Consultant Psychiatrist, Doncaster and South Humber Healthcare NHS Trust), Alex Richardson (University of Oxford, Food and Behaviour Research), Linda Seymour (Mentality), Andrew Whitley (The Village Bakery) and Kate Williams (Chief Dietician, South London and Maudsley NHS Trust). We would also like to thank the Mental Health Foundation and the Tudor Trust for providing funding for the production of this report. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily the views of those acknowledged or of Sustain's membership, individually or collectively. -

Key to Adventure Challenge

Key to Adventure Challenge Save Ink and Paper - Check the pages and please only print what you need or set to print 2 pages per A4 sheet Updated Version 1 – September 2016 Key to Adventure This challenge is designed for all sections of Girlguiding and can be completed by undertaking at least 5 challenges from different sections (or do more if you wish) plus the Coin Tree. Any proceeds from this challenge will be used to financially support the ongoing regeneration and upgrade of the facilities at Stoke Ash, Suffolk’s new county base (see page 12 for details). Our challenge is based on themes from life in Suffolk and each section is based on each letter of the words Stoke Ash. With our county symbol being a key; we would like to unlock your adventurous side whilst introducing you to our wonderful county. It is designed to be flexible so leaders can adapt it to make it fit into what time and facilities you have available locally. However, it should remain a challenge – not everything should be from the easier options we have included. There are lots of ideas but limited resources with this pack as this will allow you to use whatever resources you can find either locally, in books or online to fit the challenge. These are the Sections: S – Suffolk Punches & Farming T – Transport A – Artists & Sport O – Open Skies S – Seaside K – Kestrels & Amazing Wildlife H – History & Beautiful Buildings E - Explore new places around you Finally, if you feel you can, as part of this challenge we would like you to have some fundraising fun by making your own Coin ‘Ash’ Tree. -

David Horrobin

A CEO LOOKS AT PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY David Horrobin I usually ask medical people why they went into medicine, but in your case it’s more appropriate to ask why you left it? Mainly because I was interested in too many things. I didn’t want to get railroaded down a particular speciality. I felt that from a position in clinical physiology, I could do lots and lots of clinical projects. So I stayed in basic science but have primarily spent my life doing clinically oriented work. Physiology in Oxford involved what? I did a year working with Geoffrey Harris. He was the person who first demonstrated the pituitary is controlled by the hypothalamus. And that really I suppose in many ways shaped what I was interested in from then on – how does the brain control the hormonal system? I did clinical medicine but I’d worked as a flying doctor when I was a medical student in Kenya, and was so fascinated by Kenya that I wanted to go back. So when a new medical school there was looking for a clinical physiologist to start their physiology programme, I went out and worked for four years in the medical school. The odd event that really shaped the future, and that directed me down a psychiatric as opposed to other routes happened there. A physiologist called Howard Burn from Berkeley, California, a real superstar in the field of prolactin research, came out, funded by the US embassy, to give a lecture. The way these things used to work – the US Embassy had no idea who he was supposed to be lecturing to or anything, it was a sort of cultural thing, so I got a call from the US Ambassador saying “I’ve got this hotshot from the University of California can you find an audience for him?” It was the middle of the vacation so the only people around were a zoology professor called Mohamed ?? and myself. -

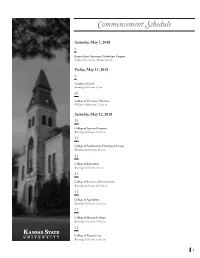

Commencement Schedule

Commencement Schedule Saturday, May 5, 2018 6 Kansas State University Polytechnic Campus Student Life Center, Salina, 10 a.m. Friday, May 11, 2018 9 Graduate School Bramlage Coliseum, 1 p.m. 29 College of Veterinary Medicine McCain Auditorium, 3:30 p.m. Saturday, May 12, 2018 31 College of Arts and Sciences Bramlage Coliseum, 8:30 a.m. 39 College of Architecture, Planning & Design McCain Auditorium, 10 a.m. 41 College of Education Bramlage Coliseum, 11 a.m. 45 College of Business Administration Bramlage Coliseum, 12:30 p.m. 51 College of Agriculture Bramlage Coliseum, 2:30 p.m. 57 College of Human Ecology Bramlage Coliseum, 4:30 p.m. 63 College of Engineering Bramlage Coliseum, 6:30 p.m. 1 CelebratingOur Future Dear Graduates, On behalf of Kansas State University, we extend our sincerest congratulations and best wishes on your graduation. Your degree represents work and commitment on your part and on the part of those who have helped you along your way. Whether it is your family, friends, faculty, staff or fellow students, know that all are proud of your accomplishments. Commencement marks a milestone in your life and sets you on a journey toward a productive and fulfilling career. We hope you use the knowledge and preparation you received at K-State to move forward and make a difference throughout your life, whether in the career field, in the community or in other worthy pursuits. As you embark and progress in your career and life, know that Kansas State University will always encourage you along the way. -

2005 Printable Program

HONORS BACCALAUREATE Honors Baccalaureate and Celebration of Academic Excellence North Carolina State University May 12, 2005 McKimmon Conference and Training Center 2005 Honors Baccalaureate and Celebration of Academic Excellence Acknowledgements The following have contributed significantly to the success of the Honors Baccalaureate and Celebration The Alma Mater of Academic Excellence: University Honors Program Words by Alvin M. Fountain, ‘23 Music by Bonnie F. Norris, ‘23 Office of Professional Development, McKimmon Conference and Training Center NC State Alumni Association Where the winds of Dixie softly blow O’er the fields of Caroline, The Grains of Time Mike Adelman, Zach Barfield, David Brown, Nathaniel Harris, Mack Hedrick, There stands ever cherished NC State, Carson Swanek, James Wallace As thy honored shrine. The SaxPack Casey Byrum, Ryan Guerry, Ashleigh Nagel, Jeremy Smith, and Tony Sprinkle So lift your voices; loudly sing From hill to oceanside! Communication Services NCSU Bookstores Our hearts ever hold you, NC State, In the folds of our love and pride. University Graphics Registration and Records The College Awards Contacts who helped to compile the list of faculty awards: Barbara Kirby and Cheri Hitt (Agriculture & Life Sciences); Jacki Robertson, Carla Skuce, and Michael Pause (Design); Billy O’Steen (Education); Martha Brinson (Engineering); David Shafer and Todd Marcks (Graduate School); Marcella Simmons (Humanities & Social Sciences); Anna Rzewnicki (Management); Robin Hughes (Natural Resources); Winnie Ellis (Physical & Mathematical Sciences); Emily Parker (Textiles); Phyllis Edwards (Veterinary Medicine) This program is prepared for informational purposes only. The appearance of an indvidual’s name does not constitute the University’s acknowledgement, certification, or representation that the individual has fulfilled the requirements for a degree or actually received the indicated designations, awards, or recognitions. -

L#F:#Llil'c'r'fex Artof Scientificendeavour

Featrrt Manchestermeeting Ca2*phase es emerge Aminoacidtransporters l#f:#llil'c'r'fex Artof scientificendeavour )-.----- '^r1-'/4 ij-- * © Jenny Hersson-Ringskog ‘My time is up and very glad I am, because I have been leading myself right up to a domain on which I should not dare to trespass, not even in an Inaugural Lecture. This domain contains the awkward problems of mind and matter about which so much has been talked and so little can be said, and having told you of my pedestrian disposition, I hope you will give me leave to stop at this point and not to hazard any further guesses.’ (closing words of Bernard Katz’s Inaugural Lecture, 1952) PHYSIOLOGYNEWS Contents The Society Dog Published quarterly by the Physiological Society Contributions and Queries Executive Editor Linda Rimmer The Physiological Society Editorial 3 Publications Office Printing House Manchester meeting Shaftesbury Road Physiology and Pharmacology in Manchester Arthur Weston 4 Cambridge CB2 2BS Tel: 01223 325 524 Features 2+ Fax: 01223 312 849 Ca phase waves emerge Dirk van Helden, Mohammed S. Imtiaz 7 Email: [email protected] Role of cationic amino acid transporters in the regulation of nitric oxide The society web server: http://www.physoc.org synthesis in vascular cells Anwar R. Baydoun, Giovanni E. Mann 12 Not for giant axons only Andrew Packard 16 Magazine Editorial Board Editor Colour and form in the cortex Daniel Kiper 19 Bill Winlow (Prime Medica, Knutsford) Deputy Editor Images of physiology Thelma Lovick 21 Austin Elliott (University of Manchester) Members Affiliate News Munir Hussain (University of Liverpool) The art of scientific endeavour Keri Page 23 John Lee (Rotherham General Hospital) Thelma Lovick (University of Birmingham) Letters to the Editor 25 Keri Page (University of Cambridge) Society News © 2003 The Physiological Society ISSN 1476-7996 Review of Society grants Maggie Leggett 26 Biosciences Federation Maggie Leggett 27 The Society permits the single copying of Hot Topics Brenda Costall 27 individual articles for private study or research. -

Cheltlf12 Brochure

SponSorS & SupporterS Title sponsor In association with Broadcast Partner Principal supporters Global Banking Partner Major supporters Radio Partner Festival Partners Official Wine Working in partnership Official Cider 2 The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival dIREctor Festival Assistant Jane Furze Hannah Evans Artistic dIREctor Festival INTERNS Sarah Smyth Lizzie Atkinson, Jen Liggins BOOK IT! dIREctor development dIREctor Jane Churchill Suzy Hillier Festival Managers development OFFIcER Charles Haynes, Nicola Tuxworth Claire Coleman Festival Co-ORdinator development OFFIcER Rose Stuart Alison West Welcome what words will you use to describe your festival experience? Whether it’s Jazz, Science, Music or Literature, a Cheltenham Festival experience can be intellectually challenging, educational, fun, surprising, frustrating, shocking, transformational, inspiring, comical, beautiful, odd, even life-changing. And this year’s The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival is no different. As you will see when you browse this brochure, the Festival promises Contents 10 days of discussion, debate and interview, plus lots of new ways to experience and engage with words and ideas. It’s a true celebration of 2012 NEWS 3 - 9 the power of the word - with old friends, new writers, commentators, What’s happening at this year’s Festival celebrities, sports people and scientists, and from children’s authors, illustrators, comedians and politicians to leading opinion-formers. FESTIVAL PROGRAMME 10 - 89 Your day by day guide to events I can’t praise the team enough for their exceptional dedication and flair in BOOK IT! 91 - 101 curating this year’s inspiring programme. However, there would be no Festival Our Festival for families and without the wonderful enthusiasm of our partners and loyal audiences and we young readers are extremely grateful for all the support we receive. -

Vol 8 No 4 Published 12/01/2016

IQNexus IQ Nexus Journal Vol. VIII, No. IV/ December 2016 http://iqnexus.org/Journal Researchers U of U Health Care in 2013 Debunked Myth of "Right-brain" and "Left-brain" Personality Traits Inside The Groundbreaking Paradigm Shift: Triadic Dimensional-Distinction Vortical Paradigm (“TDVP”) Science & Philosophy A series of dialogues papers, essays, dialogues, reviews Fine Arts music, poems, visual gallery Puzzles, Riddles & Brainteasers sudoku, matrices, verbals IQN Calendar Online Journal of IIS, ePiq & ISI-S Societies, members of WIN Officers and Editors Societies involved: IQ Nexus Journal staff The IIS IQNexus President...................... Stanislav Riha Publisher/Graphics Editor... .......Stanislav Riha Vice-President............. Harry Hollum English Editor..............................Jacqueline Slade Membership Officer.....Victor Hingsberg Test Officer.................. Olav Hoel Dørum Web Administrator & IQ Nexus founder.........................Owen Cosby The ePiq S President......................Stanislav Riha Vice-President..............Jacqueline Slade Journal Website; http: //iqnexus.org/ Test Officer...................Djordje Rancic Michael Chew Membership Officer.....Gavan Cushnahan Special acknowledgement to Torbjørn Brenna Owen Cosby For reviving and restoring The Isi-s Special thanks to Infinity International Society Administrators..............Stanislav Riha and establishing IQ Nexus Jacqueline Slade Braco Veletanlic joined forum of IIS and ePiq for her great help and later ISI-S Societies with English editorial work. This issue featuring for which this Journal was created. creative works of: “Even though scientist are involved Alena Plíštilová in this Journal,I and all involved Edward R Close in the IQ Nexus Journal Jaromír M Červenka have tried to keep the content Jason Munn (even though it is a John McGuire Hi IQ Society periodical) Kit O’Saoraidhe on an ordinary human level Louis Sauter as much as possible. -

East to West Migration in Europe, Seen from the Perspective of the British Press Pavla Cekalova1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Policy Documentation Center eumap.org Monitoring human rights and the rule of law in Europe Features > April 2008 > “Across Fading Borders: The Challenges of East-West Migration in the EU” ‘At Least They Are the Right Colour’: East to West Migration in Europe, Seen from the Perspective of the British Press Pavla Cekalova1 After the enlargement of the EU in 2004, immigration from the new EU Member States to the United Kingdom has grown into what the Office for National Statistics has called “the largest single wave of foreign in-movement ever experienced by the UK.”2 To see this East to West migration process in Europe from the perspective of the British press reveals how the choices made by the media in their reporting can reinforce existing xenophobia, racism and prejudices and create a feeling of hostility among the population. Statistical characterisations like the above, for example, have been the perfect foil for sensationalist stories, which described an “invasion” of Britain by “floods” of immigrants who were going to “swamp” the country.3 Media reporting, however, can also encourage coexistence, by countering prejudices and fears and emphasizing the benefits that the arrival of the newcomers has yielded for the country. This article presents some of the most common perspectives that dominated in the British press regarding the Central and Eastern European newcomers who arrived after the EU enlargement in 2004.4 There has been a clear division in how the issue of immigration from Central and Eastern Europe after the EU enlargement in 2004 has been covered by the British press. -

The Newsletter Number Fourteen 2010

Thomas Lovell Beddoes Society Woodcut of The Dance of Death, from the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493 The Newsletter Number Fourteen 2010 Beddoes to his Critic ‘Tell the students I obsess, Tell them something’s wrong with me. That medicine will help. Impress Them with your sage psychiatry. ‘Tell them that I’m manic, that These phases alternate with gloom. When others stood for Life, I sat. Let these statements fill the room. ‘And if perhaps you find one doubt, Resist your observations, then, Let the final clincher out: Tell them that I favored men. ‘But when you’ve thus disposed of me, And kept yourself from facing death, Do not think we’re finished. See, I await your dying breath.’ Richard Geyer aris 1856 Alphabet of Death ’s , repro P Frame from Hans Holbein Editorial Welcome to Newsletter 14. It’s two years since the last issue – poor form for an annual! – but here’s evidence that something’s still astir on the Ship of Fools. Members will know that following John Beddoes’ resignation as chairman the Society is in a period of transition. The meeting on 13th March resolved that we will continue to pursue our original aim to publicise and promote the work of Thomas Lovell Beddoes. But there are still difficulties to overcome, the most urgent being to appoint a new chairman and secretary. This must be done at the AGM on 25th September (1 pm at The Devereux, 20 Devereux Court, Essex Street, The Strand, London WC2R 3JJ). We hope that by holding the meeting in London as many members as possible will be able to attend and join the discussion: the Society needs you. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Reaseheath's Principal Honoured by OBE Young Designer Strikes First

COLLEGE The latest news from Reaseheath College issue 18 Reaseheath’s Principal honoured by OBE easeheath College Principal Meredydd’s wife Lisa, son Thomas, 26, RMeredydd David has received his and daughter Cerys, 22. The couple’s OBE from HRH The Prince of Wales. second son, Owain, joined the family later. Meredydd, who became head of Since Meredydd’s appointment, our college in 2004, was selected for Reaseheath’s student numbers and the 2009 Queen’s Birthday Honours in income have doubled and our college recognition of his outstanding services has gained recognition as being one of to local and national Further Education. the premier land based colleges in Britain. He spent several moments at Reaseheath’s raft of awards include his investiture chatting to Prince an ‘Outstanding’ Ofsted and Beacon Charles, who recalled visiting our food college status. We have also gained manufacturing halls in 2005. Training Quality Standard (TQS) for Meredydd said: “It was a wonderful the way we respond to the needs of occasion and a very proud moment. employers. The ceremony was beautiful and I As well as taking the lead at was honoured to accept the OBE on Reaseheath, Meredydd is on the behalf of colleagues at Reaseheath. Board of Directors for LSIS, the It was recognition of the wonderful learning skills improvement service, achievements that Reaseheath has and he is chairman of Landex, the made both locally and nationally land-based colleges’ federation. He - success which can be attributed is also a council member for Lantra, to our team’s dedication and the sector skills council, chairman of Principal Meredydd David is professionalism.” the LSC Technical Funding Advisory invested with his OBE by HRH The ceremony, in the ballroom at Group, and on the North West Rural The Prince of Wales.