What Grammar for Bamileke Languages? a Common Grammar Or a ‘Library’ of Grammars?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

AR 08 SIL En (Page 2)

Annual Report Being Available for Language Development > Word of the Director Laying the foundation In 1992 my wife and I visited the Boyo Division for the first time. We researched the effectiveness of the Kom mother tongue education project. I rode around on the motorbike of the literacy coordinator of the language project, and I enjoyed the scenic vistas and the challenge of travelling on mountainous roads, but above all the wonderful hospitality of the people. My time there made it very clear to me that for many children mother ton- gue education is indispensable in order to succeed in life. Many of them could not read after years of schooling in English! I vowed that my own contribution to language development in Cameroon would be to help chil- dren learn to read and write in their own language first. I made myself available so that children would learn better English, would be proud of their own culture and would be able to help build a better Cameroon. 2 Fifteen years later, I am still just as committed to that goal . I am exci- ted to see mother tongue education flourish again in the Kom area. Over the years SIL helped establish the Operational Programme for Administration the Teaching of Languages in Cameroon (PROPELCA) in many lang- in Cameroon in December 2007 uages in Cameroon, hand in hand with organisations like the National Association of Cameroon Language Committees (NACAL- George Shultz, CO) and the Cameroon Association for Bible Translation and Literacy General Director Steve W. Wittig, Director of (CABTAL). It started as an experiment with mother tongue education General Administration but has grown beyond that. -

Mankon, Bambili, Nkwen, Pinyin, and Awing Bamenda

Rapid Appraisal Sociolinguistic Survey among the NGEMBA Cluster of Languages: Mankon, Bambili, Nkwen, Pinyin, and Awing Bamenda, Santa, and Tubah Subdivisions Mezam Division North West Province Michael Ayotte Melinda Lamberty SIL International 2002 2 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 LOCATION 1.2 THE CLUSTER APPROACH TO LANGUAGES 1.2.1 Summary of Previous Research 1.2.2 Definition 1.2.3 Research Objectives for the Cluster 1.3 LINGUISTIC CLASSIFICATION AND ETHNOLOGUE INFORMATION 1.3.1 ALCAM 1.3.2 Ethnologue 1.4 DEMOGRAPHIC SITUATION 1.5 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 2 METHODOLOGY 2.1 SOCIOLINGUISTICS: RAPID APPRAISAL 2.2 INHERENT INTELLIGIBILITY: RECORDED TEXT TESTING (RTT) 2.2.1 Purpose 2.2.2 Description 2.2.3 Selection of Participants 2.2.4 Screening of Participants 2.2.5 Interpretation of RTT Results 3 RESEARCH RESULTS 3.1 MANKON [ETHNOLOGUE: DIALECT OF THE NGEMBA LANGUAGE] 3.1.1 Dialect Situation 3.1.2 Multilingualism 3.1.3 Language Vitality and Viability 3.1.4 Language Attitudes 3.1.5 Summary 3.2 BAMBILI DIALECT OF BAMBILI-BAMBUI LANGUAGE 3.2.1 Bambili Dialect Situation 3.2.2 Multilingualism 3.2.3 Language Vitality and Viability 3.2.4 Attitudes Toward Other Languages 3.2.5 Summary 3.3 BAMBUI DIALECT OF BAMBILI-BAMBUI LANGUAGE 3.3.1 Dialect Situation 3.3.2 Multilingualism 3.3.3 Language Vitality and Viability 3.3.4 Attitudes Toward Other Languages 3.3.5 Summary 3.4 MENDANKWE DIALECT OF MENKDANKWE-NKWEN LANGUAGE 3.4.1 Dialect Situation 3.4.2 Multilingualism 3.4.3 Language Vitality and Viability 3.4.4 Attitudes Toward Other Languages 3.4.5 Summary -

The Dynamics of Bilingual Adult Literacy in Africa: a Case Study of Kom, Cameroon

The Dynamics of Bilingual Adult Literacy in Africa: A Case Study of Kom, Cameroon Jean Seraphin Kamdem THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 2010 ProQuest Number: 11015877 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015877 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 DECLARATION OF OWNERSHIP I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own work and has not been written for me in whole or part by any other person. Signed: J. S. Kamdem 2 | SOA Q lARY ABSTRACT This thesis investigates, describes and analyses adult literacy in local languages in Africa, with a focus on Kom, a rural community situated in the North West province of Cameroon. The thesis presents the motivations, relevance, importance and aims of the research; then gives an overview of the national and local backgrounds, namely Cameroon and Kom. A detailed description is given of the multilingual landscape and language use in formal education, the development of writing systems for Cameroonian languages, the official literacy activities at the national level, and the Kom language and community. -

Motivations, Challenges, and Perspectives for the Development of a Deep Learning Based Automatic Speech Recognition System for the Under-Resourced Ngiemboon Language

Motivations, Challenges, and Perspectives for the Development of a Deep Learning based Automatic Speech Recognition System for the Under-resourced Ngiemboon Language Patrice A. Yemmene Laurent Besacier School of Engineering Laboratoire Informatique de Grenoble University of Saint Thomas, MN, USA University of Grenoble, France [email protected] [email protected] Abstract systems for automatic speech recognition were mostly guided by the theory of acoustic-phonetics, which Nowadays, a broad range of speech recognition describes the phonetic elements of speech (the basic technologies (such as Apple Siri and Amazon sounds of the language) and tries to explain how they Alexa) are developed as the user interface has are acoustically realized in a spoken utterance” (Juang become ever convenient and prevalent. Machine learning algorithms are yielding better training and Rabiner, 2005). These efforts date back to the early results to support these developments in 50s. Since then, ASR has yielded incredible Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR). development in a broad range of commercial However, most of these developments have been technologies where Speech Recognition as the user in languages with worldwide, political, economic interface has become ever useful and pervasive. and/or scientific influence such as English, However, most of these developments have been in Japanese, German, French, and Spanish, just to languages with strong scientific, political, and/or name a few. On the other hand, there has been economic influences such as English, German, French, little or no development of ASR systems (or and to some extent Japanese and Spanish, just to name a language technologies) in most minority and few. -

Language Policies in African States – Updated, January 2012*

Language Policies in African States – Updated, January 2012* Ericka A. Albaugh Department of Government and Legal Studies Bowdoin College 9800 College Station Brunswick, ME 04011 Comments on the accuracy of coding are welcomed. Please address them to: [email protected] * Coding is refined and descriptions updated in Appendix A of Ericka A. Albaugh, State-Building and Multilingual Education in Africa (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014). General trends remain the same. 1 TABLE A.1: CODING OF LANGUAGE USE IN EDUCATION Country Indep or 1960 1990 2004 2010 Algeria 0 2 2 2 Angola 0 0 0 4 Benin 0 0 3 3 Botswana 5 7 5 5 Burkina Faso 0 0 6 6 Burundi 7 7 7 7 Cameroon 0 0 4 4 Cape Verde 0 0 0 0 Central African Republic 0 0 0 0 Chad 0 1 4 4 Comoros 0 0 0 0 Congo, Dem. Rep. 4 8 8 8 Congo, Rep. 0 0 0 0 Cote d'Ivoire 0 0 4 4 Djibouti 0 0 0 4 Equatorial Guinea 0 0 0 0 Eritrea 10 N/A 10 10 Ethiopia 9 9 10 8 Gabon 0 0 0 0 Gambia 0 0 0 0 Ghana 0 8 4 4 Guinea 0 0 0 4 Guinea-Bissau 0 3 0 0 Kenya 0 8 6 6 Lesotho 7 7 7 7 Liberia 0 0 0 0 Madagascar 0 7 7 7 Malawi 8 7 6 5 Mali 0 4 6 6 Mauritania 1 4 1 1 Mauritius 0 0 0 0 Mozambique 0 0 4 6 Namibia 8 8 6 6 Niger 0 4 6 6 Nigeria 8 8 8 8 Rwanda 7 7 7 7 Sao Tome e Principe 0 0 0 0 Senegal 0 0 4 4 Seychelles 0 7 7 7 Sierra Leone 4 6 4 4 Somalia 1 7 5 5 South Africa 10 8 6 6 Sudan 1 2 4 4 Swaziland 0 7 5 5 Tanzania 5 9 9 9 Togo 0 0 0 0 Uganda 8 8 6 6 Zambia 0 0 4 4 Zimbabwe 4 6 6 4 2 For the coding in the table above, I distinguish between one or several languages used in education, and the extent the policy has penetrated the education system: “Experimental,” “Expanded,” or “Generalized.” The scale tries to capture the spectrum of movement from “most foreign” medium to “most local.” The numerical assignments describe the following situations: 0 European Language Only 1 European and Foreign African Language (e.g. -

The Nweh Narrative Genre: Implications on the Pedagogic Role of Translation

Justina Njika (Autor) The Nweh Narrative Genre: Implications on the Pedagogic Role of Translation https://cuvillier.de/de/shop/publications/314 Copyright: Cuvillier Verlag, Inhaberin Annette Jentzsch-Cuvillier, Nonnenstieg 8, 37075 Göttingen, Germany Telefon: +49 (0)551 54724-0, E-Mail: [email protected], Website: https://cuvillier.de Introduction 0.1 Aims and objectives This book explores some of the many facets of the narrative genre contained in the Nweh language of the Republic of Cameroon. The study, which is based on the author’s-guided collections of Nweh narratives, draws insight from the basic principles of Discourse Analysis (DA) to describe the nature and function of the Nweh narratives. The relevance of such knowledge to meaning-based translation as a useful pedagogic device in the contexts of Second Language Acquisition (SLA), is also depicted in the study. 0.2 Linguistic situation of Cameroon Language is one of man’s major assets; it serves as a mark of communal and individual identity. Before the colonial era, Africa enjoyed an integral and coherent traditional society. Yet, this socio- cultural serenity of the continent was Map 1: Cameroon (Administrative Regions) seriously upset during the colonial decades. Cameroon, one of the Sub Saharan African nations, suffered a grievous linguistic setback. The country, which adopts at least 250 indigenous languages, (Tadadjeu 1975), was exposed to three different colonial administrations (the German, the English and the French) with dissimilar linguistic contacts and policies. These varied colonial administrations resulted to the institution of two official languages (French and English) after independence (1960/1961), with Cameroon Pidgin English as a Lingua Franca. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Aguna in Benin Aja in Benin Population: 20,000 Population: 993,000 World Popl: 38,000 World Popl: 1,228,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: Yoruba People Cluster: Guinean Main Language: Aguna Main Language: Aja Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Partially reached Status: Significantly reached Evangelicals: 8.0% Evangelicals: 11.0% Chr Adherents: 35.0% Chr Adherents: 30.0% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Portions www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Kerry Olson "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Anii in Benin Anufo, Chokossi in Benin Population: 47,000 Population: 25,000 World Popl: 66,000 World Popl: 229,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: Guinean People Cluster: Guinean Main Language: Anii Main Language: Anufo Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Partially reached Evangelicals: 1.00% Evangelicals: 5.0% Chr Adherents: 2.00% Chr Adherents: 10.0% Scripture: Unspecified Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Kerry Olson Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Batonu, Baruba in Benin Biali in Benin Population: 953,000 Population: 167,000 World Popl: 1,381,000 World Popl: 173,600 Total Countries: 4 Total -

RAPID APPRAISAL SOCIOLINGUISTIC LANGUAGE SURVEY of NGAMAMBO of CAMEROON* Lilian Lem (University of Dschang) Edward Brye (SIL)

RAPID APPRAISAL SOCIOLINGUISTIC * LANGUAGE SURVEY OF NGAMAMBO OF CAMEROON Lilian Lem (University of Dschang) Edward Brye (SIL) SIL International 2008 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2008-008, June 2008 Copyright © 2008 Lilian Lem, Edward Brye, and SIL International All rights reserved 2 CONTENTS ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Names 1.2 Locality and Population 1.3 History of the Ngamambo Speech Community 1.4 Linguistic Classification 1.5 Purpose of Survey 1.6 Background 2 METHODOLOGY 2.1 Rapid Appraisal 2.2 The Ngamambo Survey 3 RESEARCH RESULTS 3.1 Lexicostatistics 3.2 Dialect Situation 3.3 Multilingualism 3.3.1 Mother Tongue Use 3.3.2 English Language Use 3.3.3 Pidgin English Language Use 3.4 Language Vitality and Viability 3.4.1 Language Attitudes 3.4.2 Language Development Potential 3.5 Attitudes towards Language Development 4 SIL/CABTAL/NACALCO: ACTIVITIES AND PLANS 5 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS APPENDIX 1: ALCAM Lists for Ngamambo (3), Moghamo (1), and Meta (1) APPENDIX 2: Linguistic Map of Ngamambo and Neighboring Languages REFERENCES 3 ABSTRACT This report presents the findings of a sociolinguistic survey (Rapid Appraisal) of the Ngamambo speech community in the North West Province of Cameroon. Research was conducted in 2002 for the purpose of assessing the need for literacy and development of Ngamambo and closely related speech varieties. This survey includes 120-item wordlists from the Ngamambo, Moghamo, and Meta speech varieties. 1 INTRODUCTION This report describes a sociolinguistic survey (Rapid Appraisal) of the Ngamambo speech community conducted June 18–20, 2002 in three villages in the Santa Subdivision of the Mezam Division of the North West Province of Cameroon. -

Phonological Characteristics of Eastern Grassfields Languages

/DQJXDJHDQG&XOWXUH$UFKLYHV Phonological characteristics of Eastern Grassfields languages Stephen C. Anderson ©2006, SIL International and Stephen C. Anderson License This document is part of the SIL International Language and Culture Archives. It is shared ‘as is’ in order to make the content available under a Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivativeWorks (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). More resources are available at: www.sil.org/resources/language-culture-archives. (corrected version of) Anderson, Stephen C. (2001) Phonological Characteristics of Eastern Grassfields Languages. In Nguessimo M. Mutaka and Sammy B. Chumbow, ed. Research Mate in African Linguistics: Focus on Cameroon, 33-54. Jnkm9QtchfdqJnoodUdqkf. Phonological Characteristics of Eastern Grassfields Languages Stephen C. Anderson, SIL-Cameroon 1. Introduction This paper1 presents a brief description of phonetic and phonological features common to Eastern Grassfields languages. It aims to give a quick introduction to researchers interested in this language family while referring them to the bibliography for descriptions that go into greater detail. Because of the author's familiarity with the Ngiemboon language, all examples in this paper will be from that language unless otherwise noted. Because of the genetic relationships, many of the details described in this paper will also hold true for the Narrow Grassfields language family in general. However, because Ngiemboon is a very conservative member of this family and has an unusually -

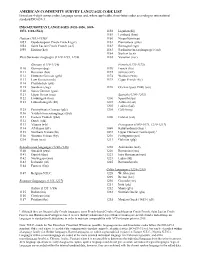

American Community Survey Language Code List

AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY LANGUAGE CODE LIST Listed are 4-digit census codes, language names and, where applicable, three-letter codes according to international standard ISO 639-3. INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES (1053-1056, 1069- 1073, 1110-1564) 1158 Ligurian (lij) 1159 Lombard (lmo) Haitian (1053-1056)1 1160 Neapolitan (nap) 1053 Guadeloupean Creole French (gcf) 1161 Piemontese (pms) 1054 Saint Lucian Creole French (acf) 1162 Romagnol (rgn) 1055 Haitian (hat) 1163 Sardinian (macrolanguage) (srd) 1164 Sicilian (scn) West Germanic languages (1110-1139, 1234) 1165 Venetian (vec) German (1110-1124) French (1170-1175) 1110 German (deu) 1170 French (fra) 1111 Bavarian (bar) 1172 Jèrriais (nrf) 1112 Hutterite German (geh) 1174 Walloon (wln) 1113 Low German (nds) 1175 Cajun French (frc) 1114 Plautdietsch (ptd) 1115 Swabian (swg) 1176 Occitan (post 1500) (oci) 1120 Swiss German (gsw) 1121 Upper Saxon (sxu) Spanish (1200-1205) 1122 Limburgish (lim) 1200 Spanish (spa) 1123 Luxembourgish (ltz) 1201 Asturian (ast) 1202 Ladino (lad) 1125 Pennsylvania German (pdc) 1205 Caló (rmq) 1130 Yiddish (macrolanguage) (yid) 1131 Eastern Yiddish (ydd) 1206 Catalan (cat) 1132 Dutch (nld) 1133 Vlaams (vls) Portuguese (1069-1073, 1210-1217) 1134 Afrikaans (afr) 1069 Kabuverdianu (kea) 1 1135 Northern Frisian (frr) 1072 Upper Guinea Crioulo (pov) 1 1136 Western Frisian (fry) 1210 Portuguese (por) 1234 Scots (sco) 1211 Galician (glg) Scandinavian languages (1140-1146) 1218 Aromanian (aen) 1140 Swedish (swe) 1220 Romanian (ron) 1141 Danish (dan) 1221 Istro Romanian (ruo)