Lend Lease 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collection

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collection Charles C. Bush, II, Collection Bush, Charles C., II. Papers, 1749–1965. 5 feet. Professor. Instructional materials (1749–1965) for college history courses; student papers (1963); manuscripts (n.d.) and published materials (1941–1960) regarding historical events; and correspondence (1950–1965) to and from Bush regarding historical events and research, along with an original letter (1829) regarding Tecumseh and the Battle of the Thames in 1813, written by a soldier who participated. Instructional Materials Box 1 Folder: 1. Gilberth, Keith Chesterton (2 copies), n.d. 2. The Boomer Movement Part 1, Chapters 1 and 2, 1870-1880. 3. Washington and Braddock, 1749-1755. 4. Washita (1) [The Battle of], 1868. 5. Cheyenne-Arapaho Disturbones-Ft. Reno, 1884-1885. 6. 10th Cav. Bibb and Misel, 1866-1891 1 Pamphlet "Location of Classes-Library of Congress", 1934 1 Pamphlet "School Books and Racial Antagonism" R. B. Elfzer, 1937 7. Speech (notes) on Creek Crisis Rotary Club, Spring '47, 1828-1845. 8. Speech-Administration Looks at Fraternities (2 copies), n.d. 9. Speech YM/WCA "Can Education Save Civilization", n.d. 10. Durant Commencement Speech, 1947. 11. Steward et al Army, 1868-1879. 12. ROTC Classification Board, 1952-1954. 13. Periodical Material, 1888-1906. 14. The Prague News Record - 50th Anniversary, 1902-1951 Vol. 1 7/24/02 No. 1 Vol. 50 8/23/51 No. 1 (2 copies) 15. Newspaper - The Sunday Oklahoma News - Sept. 11 (magazine section) "Economic Conditions of the South", 1938 16. Rockefeller Survey - Lab. Misc. - Course 112 Historic sites in Anadarko and Caddo Counties, Oklahoma - Oklahoma Historical Society, 1884 17. -

Red Dirt Resistance: Oklahoma

RED DIRT RESISTANCE: OKLAHOMA EDUCATORS AS AGENTS OF CHANGE By LISA LYNN Bachelor of Arts in Psychology University of Oklahoma Norman, OK 1998 Master of Science in Applied Behavioral Studies Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 2001 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2018 RED DIRT RESISTANCE: OKLAHOMA EDUCATORS AS AGENTS OF CHANGE Dissertation Approved: Jennifer Job, Ph.D. Dissertation Adviser Pamela U. Brown, Ph.D. Erin Dyke, Ph.D. Lucy E. Bailey, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Jennifer Job for her tireless input, vision, and faith in this project. She endured panicked emails and endless questions. Thank you for everything. I would also like to thank Dr. Erin Dyke, Dr. Pam Brown, and Dr. Lucy Bailey for their support and words of encouragement. Each of you, in your own way, gently stretched me to meet the needs of this research and taught me about myself. Words are inadequate to express my gratitude. I would also like the thank Dr. Moon for his passionate instruction and support, and Dr. Wang for her guidance. I am particularly grateful for the friendship of my “cohort”, Ana and Jason. They and many others carried me through the rough spots. I want to acknowledge my mother and father for their unwavering encouragement and faith in me. Finally, I need to thank my partner, Ron Brooks. We spent hours debating research approaches, the four types of literacy, and gender in education while doing dishes, matching girls’ socks, and walking the dogs. -

![The Green Corn Rebellion in Oklahoma [March 4, 1922] 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1973/the-green-corn-rebellion-in-oklahoma-march-4-1922-1-421973.webp)

The Green Corn Rebellion in Oklahoma [March 4, 1922] 1

White: The Green Corn Rebellion in Oklahoma [March 4, 1922] 1 The Green Corn Rebellion in Oklahoma [events of Aug. 3, 1917] by Bertha Hale White † Published in The New Day [Milwaukee], v. 4, no. 9, whole no. 91 (March 4, 1922), pg. 68. The story of the wartime prisoners of Oklahoma ceived the plan of organizing, of banding themselves is one of the blind, desperate rebellion of a people together to fight the exactions of landlord and banker. driven to fury and despair by conditions which are The result of these efforts was a nonpolitical or- incredible in this stage of our so-called civilization. ganization known as the Working Class Union. It had Even the lowliest of the poor in the great industrial but one object — to force downward rents and inter- centers of the country have no conception of the depths est rates. The center of the movement seems to have of misery and poverty that is the common lot of the been the Seminole country, where even today one tenant farmer of the South. meets more frequently the Indian than the white man. As long as we can remember, we have heard of It has been asserted by authoritative people that their exploitation. We are told that the tenant must not 1 in 15 of these tenants can read or write. It is mortgage his crop before he can obtain the seed to put obvious that very little of what is happening in the into the ground; that when the harvesting is over out world is ever very closely understood by the majority of the fruits of his labor he can pay only a part of the of them. -

For All the People

Praise for For All the People John Curl has been around the block when it comes to knowing work- ers’ cooperatives. He has been a worker owner. He has argued theory and practice, inside the firms where his labor counts for something more than token control and within the determined, but still small uni- verse where labor rents capital, using it as it sees fit and profitable. So his book, For All the People: The Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, reached expectant hands, and an open mind when it arrived in Asheville, NC. Am I disappointed? No, not in the least. Curl blends the three strands of his historical narrative with aplomb, he has, after all, been researching, writing, revising, and editing the text for a spell. Further, I am certain he has been responding to editors and publishers asking this or that. He may have tired, but he did not give up, much inspired, I am certain, by the determination of the women and men he brings to life. Each of his subtitles could have been a book, and has been written about by authors with as many points of ideological view as their titles. Curl sticks pretty close to the narrative line written by worker own- ers, no matter if they came to work every day with a socialist, laborist, anti-Marxist grudge or not. Often in the past, as with today’s worker owners, their firm fails, a dream to manage capital kaput. Yet today, as yesterday, the democratic ideals of hundreds of worker owners support vibrantly profitable businesses. -

The War to End All Wars. COMMEMORATIVE

FALL 2014 BEFORE THE NEW AGE and the New Frontier and the New Deal, before Roy Rogers and John Wayne and Tom Mix, before Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, before the TVA and TV and radio and the Radio Flyer, before The Grapes of Wrath and Gone with the Wind and The Jazz Singer, before the CIA and the FBI and the WPA, before airlines and airmail and air conditioning, before LBJ and JFK and FDR, before the Space Shuttle and Sputnik and the Hindenburg and the Spirit of St. Louis, before the Greed Decade and the Me Decade and the Summer of Love and the Great Depression and Prohibition, before Yuppies and Hippies and Okies and Flappers, before Saigon and Inchon and Nuremberg and Pearl Harbor and Weimar, before Ho and Mao and Chiang, before MP3s and CDs and LPs, before Martin Luther King and Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson, before the pill and Pampers and penicillin, before GI surgery and GI Joe and the GI Bill, before AFDC and HUD and Welfare and Medicare and Social Security, before Super Glue and titanium and Lucite, before the Sears Tower and the Twin Towers and the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, before the In Crowd and the A Train and the Lost Generation, before the Blue Angels and Rhythm & Blues and Rhapsody in Blue, before Tupperware and the refrigerator and the automatic transmission and the aerosol can and the Band-Aid and nylon and the ballpoint pen and sliced bread, before the Iraq War and the Gulf War and the Cold War and the Vietnam War and the Korean War and the Second World War, there was the First World War, World War I, The Great War, The War to End All Wars. -

Peter Thiel 47 a LONG RED SUNSET Harvey Klehr Reviews American Dreamers: How the Left COVER: K.J

2011_10_03 postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 9/13/2011 9:21 PM Page 1 October 3, 2011 49145 $4.99 JAMES LILEKS on ‘the Perry Approach’ thethe eNDeND ofof thethe futurefuture PETER THIEL PLUS: TIMOTHY B. LEE: Patent Absurdity ALLISON SCHRAGER: In Defense of Financial Innovation ROB LONG: A Farewell to Steve Jobs $4.99 40 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 9/12/2011 2:50 PM Page 2 base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 9/12/2011 2:50 PM Page 3 toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 9/14/2011 2:10 PM Page 2 Contents OCTOBER 3, 2011 | VOLUME LXIII, NO. 18 | www.nationalreview.com COVER STORY Page 28 Ramesh Ponnuru on Social Security Swift Blind p. 18 Horseman? BOOKS, ARTS There is no law that the & MANNERS exceptional rise of the West 40 THE MISSING MAN must continue. So we could do Matthew Continetti reviews Keeping worse than to inquire into the the Republic: Saving America by Trusting Americans, widely held opinion that America by Mitch Daniels. is on the wrong track, to wonder 42 BLESS THE BEASTS whether Progress is not doing Claire Berlinski reviews The Bond: as well as advertised, and Our Kinship with Animals, perhaps to take exceptional Our Call to Defend Them, by Wayne Pacelle. measures to arrest and reverse any decline. Peter Thiel 47 A LONG RED SUNSET Harvey Klehr reviews American Dreamers: How the Left COVER: K.J. HISTORICAL/CORBIS Changed a Nation, by Michael Kazin. ARTICLES 49 BUSH RECONSIDERED 18 SOCIAL SECURITY ALERT by Ramesh Ponnuru Quin Hillyer reviews The Man in Perry and Romney debate a program in need of reform. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Third parties in twentieth century American politics Sumner, C. K. How to cite: Sumner, C. K. (1969) Third parties in twentieth century American politics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9989/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "THIRD PARTIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POLITICS" THESIS PGR AS M. A. DEGREE PRESENTED EOT CK. SOMBER (ST.CUTHBERT«S) • JTJLT, 1969. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART 1 - THE PROGRESSIVE PARTIES. 1. THE "BOLL MOOSE" PROQRESSIVES. 2. THE CANDIDACY CP ROBERT M. L& FQLLETTE. * 3. THE PEOPLE'S PROGRESSIVE PARTI. PART 2 - THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF AMERICA* PART 3 * PARTIES OF LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL APPEAL. -

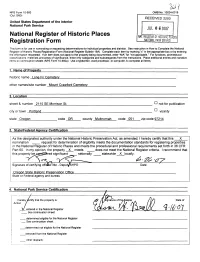

Vv Signature of Certifying Offidfel/Title - Deput/SHPO Date

NPSForm 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUL 0 6 2007 National Register of Historic Places m . REG!STi:ffililSfGRicTLA SES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE — This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classifications, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Lone Fir Cemetery other names/site number Mount Crawford Cemetery 2. Location street & number 2115 SE Morrison St. not for publication city or town Portland vicinity state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 051 zip code 97214 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties | in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR [Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Government Power and Rural Resistance in the Arkansas Ozarks

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Dynamics of Defiance: Government Power and Rural Resistance in the Arkansas Ozarks J. Blake Perkins Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Perkins, J. Blake, "Dynamics of Defiance: Government Power and Rural Resistance in the Arkansas Ozarks" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6404. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6404 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Defiance: Government Power and Rural Resistance in the Arkansas Ozarks J. Blake Perkins Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. James Siekmeier, Ph.D. Brooks Blevins, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, WV 2014 Keywords: Ozarks; Arkansas; rural; government; liberal state; populism; resistance; dissent; smallholder; agrarianism; industrialization; agribusiness; liberalism; conservatism; economic development; politics; stereotypes Copyright 2014 J. -

Springfield News

OnlvorBliyolOroBon Dol)t 01 juuuiu I JrlrL SPRINGFIELD NEWS (Hint Koirniry it. IMI.U 4 irliifttl I. 1mkii, ltrin1-nultorum- SPRINGFIELD, LANE COUNTY, OREGON, THURSDAY, MAY 24, 1917 VOL. XVI. NO. r rt ol t'nnxrn of M rli, my 34 $48 A MONTH FOR WIDOW INTERNED GERMANS TAKE EXERCISE SPUDS SAID TO BE ROTTEN CHRISTIAN CHURCH NO ONE 15 .vMri. W. P. Howill Hat 6077.34 Oe W. B. Cooper Wants His Money Any. EXEMPT Allan for her and Children. way? E, E. Morrison la Defendant MPROVEMENTS 10 FmyilKhi a month will bo W. B. Cooper Is plaintiff In a suit NOW; ALL BETWEEN I A. Mm U. V. Howell, by the stai filed early this week in circuit court Industrial u cell! cut commission which against E. E. Morrison, of Springfield li.vi iii.ulo nwtird in the claim for com In which ho seeks tho recovery of tho BE FINISHED 500 pcmii'ii I; (hu froth of Wm. K. sum of $2046.69, alleged duo on a 21 AND 30 TO Itowpll a ;r'irlitf resident, win quantity of potatoes which tho plain IN tli.O on May f tiMii Iho result of lo tiff sold him. 1 rrculvcd it no Booth-Kell- sa When asked about the suit, Mr. Prooonto Dlfforont Be Siruoturo mill n iMCDnili-- 1G, JMfl. Morrison stated that it really was not Exemptions to Determined Than It Did Mr, Howell loft u widow mid throo hlc affair at all since ho bad been act- After Completion of Regis- ing only as an agent a company Six Wookar Ago. -

1930 Journal

; ; MONDAY, OCTOBER 6, 19 3 0 -f^^ 1 SUPEEME COURT OE THE UisTITED STATES Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Van Devanter, Mr. Justice McReynolds, Mr. Justice Brandeis, Mr. Jus- tice Sutherland, Mr. Justice Butler, Mr. Justice Stone, and Mr. Justice Roberts. Louis Charney Friedman, of Paterson, N. J.; A. F. Kingdon, of Bluefield, W. Va. ; Edward H. Dell, of Middletown, Ohio ; Francis P. Farrell, of New York City; John E. Snyder, of Hershey, Pa.; Francis E. Delamore, of Little Rock, Ark.; William R. Carlisle, of New York City; William Geo. Junge, of Los Angeles, Calif.; Francis Harold Uriell, of Chicago, 111.; John Butera, of Dallas, Tex.; Alean Brisley Clutts, of Detroit, Mich.; Cornelius B. Comegys, of Scranton, Pa.; Walter J. Rosston, of New York City; John A. Coleman, of Los Angeles, Calif. Harry F. Brown, of Guthrie, Okla. ; Wm. W. Montgomery, Jr., of Philadelphia, Pa.; Joe E. Daniels, of New York City; Winthrop Wadleigh, of Milford, N. H.; Ernest C. Griffith, of Los Angeles, Calif. ; and K. Berry Peterson, of Phoenix, Ariz., were admitted to practice. No. 380* R. D. Spicer et al., petitioners, v. The United States of America No. 381. G. C. Stephens, petitioner, v. The United States of America; and No. 382. B. M. Wotkyns, petitioner, v. The United States of America. Leave granted the respondent to file brief on or before October 20, on motion of Mr. Solicitor General Thacher for the respondent. No. 5. Indian Motocycle Company v. The United States of Amer- ica. Joint motion to amend certificate submitted by Mr.