Morpho Phonemic Patterns in the Prefdgd Chapters of the Holy Qur'an: a Sty]Listic Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HRS 2006 Self-Administered Psychosocial Questionnaire

Psychosocial and Lifestyle Questionnaire 2006 - 2010 Documentation Report Core Section LB Jacqui Smith, Gwenith Fisher, Lindsay Ryan, Philippa Clarke, Jim House and David Weir The HRS Psychosocial Working Group Survey Research Center Institute for Social Research University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan February 2013 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2004 Survey Methodology ............................................................................................................... 7 2006 Survey Methodology ............................................................................................................... 7 2008 Survey Methodology ............................................................................................................... 8 2010 Survey Methodology ............................................................................................................... 8 Weighting ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Special Methodological Issues to Consider .................................................................................... 9 Response Scales ............................................................................................................................. -

An Algorithm to Measure Daily Bus Passenger Miles Using Electronic Farebox Data

An Algorithm to Measure Daily Bus Passenger Miles Using Electronic Farebox Data Alex Lu, Alla Reddy Operations Planning New York City Transit Authority Presented at the 90th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board Washington D.C. (2011) T R A N S I T New York City Transit Notice: Opinions expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official New York City Transit policy or position of Metropolitan Transportation Authority or MTA New YorkTRB City Transit. Paper #11-0368 Slide 1 Purpose and Need • Implement 100% electronic data reporting – Monthly “safety module” – Eliminates surveying, data entry, manual checking – More consistent & accurate • Algorithm requirements – Zero manual intervention – Fast: running time of a few minutes per day of data – Rely on schedules and AFC data (no GPS/AVL/APC) Photo: Adam E. Moreira New York City Transit TRB Paper #11-0368 Slide 2 NYCT’s MetroCard AFC Data • “Trip” file 73 bytes per record × about 8,000,000 bus and subway records per weekday = approximately 550 MB per weekday (3am to 2.59am next day) – partial trip records Hypothetical card with bus-only records shown: ....x....1....x....2....x....3....x....4....x....5....x....6....x....7. – no timestamps for 2653058017 20080416 55400 157 027 F02569 1 R482 0 362 2653058017 20080416 63000 157 027 F0027F 1 R480 0 494 cash transactions 2653058017 20080416 73600 157 027 F01E70 2 R494 0 153 2653058017 20080416 160000 157 027 F01E72 2 R494 0 152 2653058017 20080416 161800 157 027 F00214 1 R480 0 494 – -

Right of Passage

Right of Passage: Reducing Barriers to the Use of Public Transportation in the MTA Region Joshua L. Schank Transportation Planner April 2001 Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA 347 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10017 (212) 878-7087 · www.pcac.org ã PCAC 2001 Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank the following people: Beverly Dolinsky and Mike Doyle of the PCAC staff, who provided extensive direction, input, and much needed help in researching this paper. They also helped to read and re-read several drafts, helped me to flush out arguments, and contributed in countless other ways to the final product. Stephen Dobrow of the New York City Transit Riders Council for his ideas and editorial assistance. Kate Schmidt, formerly of the PCAC staff, for some preliminary research for this paper. Barbara Spencer of New York City Transit, Christopher Boylan of the MTA, Brian Coons of Metro-North, and Yannis Takos of the Long Island Rail Road for their aid in providing data and information. The Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee and its component Councils–the Metro-North Railroad Commuter Council, the Long Island Rail Road Commuters Council, and the New York City Transit Riders Council–are the legislatively mandated representatives of the ridership of MTA bus, subway, and commuter-rail services. Our 38 volunteer members are regular users of the MTA system and are appointed by the Governor upon the recommendation of County officials and, within New York City, of the Mayor, Public Advocate, and Borough Presidents. For more information on the PCAC and Councils, please visit our website: www.pcac.org. -

HSIP Report Template Introduction Program Structure

HSIP Report Template May 2017 [Q1] State [Q2] Executive Summary Introduction Standard text Program Structure Program Administration [Q3] Describe the general structure of the HSIP in the State. [large text question] [Q4] Where is HSIP staff located within the State DOT? [Select one] Planning Operations Design Engineering Other [Q5 (old Q3)] How are HSIP funds allocated in a State? [Select one] Central Office via Statewide Competitive Application Process SHSP Emphasis Area Data Formula via Districts/Regions Formula via MPOs Other [Q6 (old Q4)] Describe how local and tribal roads are addressed as part of HSIP. [large text question] [Q7 (old Q5)] Identify which internal partners (e.g., State departments of transportation (DOTs) Bureaus, Divisions) are involved with HSIP planning. [Check all that apply] Traffic Engineering/Safety Design Planning Maintenance Operations Districts/Regions Local Aid Programs Office/Division Governors Highway Safety Office Other [Q8 (old Q6)] Describe coordination with internal partners. [large text question] 1 HSIP Report Template May 2017 [Q9 (old Q7)] Identify which external partners are involved with HSIP planning. [Check all that apply] Regional Planning Organizations (e.g. MPOs, RPOs, COGs) Governors Highway Safety Office Local Technical Assistance Program Local Government Agency Tribal Agency Law Enforcement Agency Academia/University FHWA Other [Q10] Describe coordination with external partners. [large text question] [Q11 (old Q8)] Have any program administration practices used to implement the HSIP changed since the last reporting period? [Yes/No dropdown] [If yes] Describe HSIP program administration practices that have changed since the last reporting period. [large text question] [Q12 (old Q9)] Are there any other any other aspects of HSIP Administration on which the State would like to elaborate? [Yes/No dropdown] [If yes] Describe other aspects of HSIP Administration on which the State would like to elaborate. -

Improving Bus Service in New York a Thesis Presented to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Improving Bus Service in New York A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Architecture and Planning COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment Of the requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Urban Planning By Charles Romanow May 2018 Abstract New York City’s transportation system is in a state of disarray. City street are clogged with taxi’s and for-hire vehicles, subway platforms are packed with straphangers waiting for delayed trains and buses barely travel faster than pedestrians. The bureaucracy of City and State government in the region causes piecemeal improvements which do not keep up with the state of disrepair. Bus service is particularly poor, moving at rates incomparable with the rest of the country. New York has recently made successful efforts at improving bus speeds, but only so much can be done amidst a city of gridlock. Bus systems around the world faced similar challenges and successfully implemented improvements. A toolbox of near-immediate and long- term options are at New York’s disposal dealing directly with bus service as well indirect causes of poor bus service. The failing subway system has prompted public discussion concerning bus service. A significant cause of poor service in New York is congestion. A number of measures are capable of improving congestion and consequently, bus service. Due to the city’s limited capacity at implementing short-term solutions, the most highly problematic routes should receive priority. Routes with slow speeds, high rates of bunching and high ridership are concentrated in Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn which also cater to the most subway riders. -

Q46 Local and Limited-Stop Service

Bus Timetable Effective as of January 6, 2019 New York City Transit Q46 Local and Limited-Stop Service a Between Glen Oaks and Kew Gardens If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but our express buses (between subway and local bus, local bus and local bus etc.) Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value if you complete your transfer within two hours of the time you pay your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare with coins, ask for a free electronic paper transfer to use on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. Benefits are available (except on peak-hour express buses) with proper identification, including Reduced-Fare MetroCard or Medicare card (Medicaid cards do not qualify). Children – The subway, SIR, local, Limited-Stop, and +SelectBusService buses permit up to three children, 44 inches tall and under to ride free when accompanied by an adult paying full fare. -

Community Survey Regional Community Transportation Needs Assessment

COMMUNITY SURVEY REGIONAL COMMUNITY TRANSPORTATION NEEDS ASSESSMENT MARCH 2017 Prepared By: TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights ..........................................................................................................................................1 Overview ...........................................................................................................................................2 Sampling Approach ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Sampling Demographics ............................................................................................................................... 3 Park and Ride Services .......................................................................................................................6 Q3. Is Park and Ride Bus Service Located in Your Area? .............................................................................. 6 Q4. If yes, do you use Park and Ride service? .............................................................................................. 6 Q5. If yes, how often? .................................................................................................................................. 7 Q6. What are the primary strengths of Park and Ride service? .................................................................. 7 Q7. What are the main weaknesses of Park and Ride service? ................................................................... 9 Q8. -

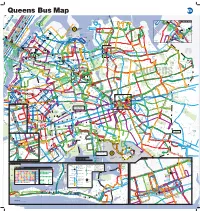

Queens Bus Map a Map of the Queens Bus Routes

Columbia University 125 St W 122 ST M 1 6 M E 125 ST Cathedral 4 1 Pkwy (110 St) 101 M B C M 5 6 3 116 St 102 125 St W 105 ST M M 116 St 60 4 2 3 Cathedral M SBS Pkwy (110 St) 2 B C M E 126 ST 103 St 1 MT MORRIS PK W 103 M 5 AV M E 124 2 3 102 10 E 120 ST M Central Park ST North (110 St) M MADISON AV 35 1 M M M B C 103 1 2 3 4 1 M 103 St 96 St 15 M 110 St 1 E 110 ST6 SBS QW 96 ST ueens Bus Map RANDALL'S BROADWAY 1 ISLAND B C 86 St NY Water 96 St Taxi Ferry W 88 ST Q44 SBS 44 6 to Bronx Zoo 103 St SBS M M MADISON AV Q50 15 35 50 WHITESTONE COLUMBUS AV E 106 ST F. KENNEDY COLLEGE POINT to Co-op City SBS 96 St 3 AV SHORE FRONT THROGS NECK BRIDGE B C BRIDGE CENTRAL PARK W 6 PARK 7 AV 2 AV BRIDGE POWELLS COVE BLVD 86 St 25 WHITESTONE CLI 147 ST N ROBERT ED KOCH LIC / Queens Plaza 96 St 5 AV AV 15A QUEENSBORO R 103 103 150 ST N 10 15 1 AV R W Q D COLLEGE POINT BLVD T 41 AV M 119 ST BRIDGE B C R 9 AV O 66 37 AV 15 FD NVILLE ST 81 St 96 ST QM QM QM QM M 7 AV 9 AV 69 38 AV 5 AV RIKERS POPPENHUSEN AV R D 102 1 2 3 4 21 St 35 NTE R 102 Queens- WARDS E 157 ST M 4 100 ISLAND 9 AV C 44 11 AV QM QM QM QM QM bridge 160 ST 166 ST 9 154 ST 162 ST 1 M M M ISLAND AV 15A 5 6 10 12 15 F M 5 6 SBS UTOPIA 39 AV 1 15 60 Q44 FORT QM QM QM QM QM 10 M 86 St COLLEGE BEECHHURST 13 Next stop QM 14 AV 15 PKWY TOTTEN 21 ST 102 M 111 ST 25 16 17 20 18 21 CRESCENT ST 2 86 St SBS POINT QM QM QM 14 AV 123 ST SERVICE RD NORTH QNS PLZ N 39 Av 2 14 AV Lafayette Av 2 QM QM QM QM QM QM M M Q 65 76 2 32 16 E 92 ST 21 AV 14 AV 20B 32 40 AV N W M 101 QM 2 24 31 32 34 35 3 LAGUARDIA 14 RD 15 AV E M E 91 ST 15 AV 32 SER 14 RD QM QM QM QM QM QM M 3 M ASTORIA WA 31 ST 101 21 ST 100 VICE RD S. -

Paratransit Peer Report Final Version - January 2011

Paratransit Peer Report Final Version - January 2011 Reporting Periods: ……… …………………... January-December 2009, July 2008-June 2009 and October 2008-September 2009 Prepared by: ,. Department of Buses Paratransit Division 130 Livingston Street Brooklyn, NY 11201 Paratransit Peer Report for Calendar Year 2009/Fiscal Year 2008-09 Introduction NEW YORK CITY TRANSIT ▪ DEPARTMENT OF BUSES ▪ PARATRANSIT DIVISION MTA New York City Transit's Paratransit Peer Report is the result of a survey conducted annually by the Department of Buses' Paratransit Division. This year's survey was distributed in spring 2010 to fourteen transit properties operating in various cities of the United States. Its purpose is to capture and share information on the many various facets of paratransit operations for the 2009 calendar year and 2008-09 fiscal year, as applicable. The information collected includes ridership, finances, eligibility and vehicles. Additional questions pertain to newly implemented technologies, alternate transportation and travel training. Responses were received from all fourteen transit properties surveyed. Counting New York City Transit, the total number of participants in this report is fifteen. The following transportation properties are identified under the noted cities. - Boston, MA The Ride - Broward County, FL Transportation Options-TOPS - Chicago, IL ADA Service - Dallas, TX DART Paratransit Services - Denver, CO access-a-Ride - Garden City, NY Able-Ride - Houston, TX METROLift - Los Angeles, CA Access Services Paratransit - Miami, FL Special -

Cunningham Park

THERE’S SOMETHING TO DO FOR EVERYONE AT CUNNINGHAM PARK- Tennis Courts- 20 HOW TO FIND US- NYC DEPARTMENT OF Baseball/Softball Fields- 24 BY CAR- PARKS & RECREATION Football Fields- 1 Soccer Fields- 3 From Grand Central Parkway- Cricket Pitches- 1 Exit at Francis Lewis Boulevard (Northbound Bocce Courts- 2 Exit). Take Francis Lewis to Union Turnpike and 2009 SEASON Basketball Courts- 2 make a left. Make your second left into the parking Playgrounds- 4 lot at 196th Place. Spray Showers- 3 From Long Island Expressway- Comfort Stations- 4 Jogging/Walking Track Exit at Francis Lewis Boulevard. Go south on WELCOME TO Biking Path (Motor Parkway-199 St./75 Ave.) Francis Lewis (make right from eastbound exit or left from westbound exit). Go to Union Turnpike Mountain Bike Trails (210 St. & 67 Ave.) CUNNINGHAM and make a right. Make your second left into the Barbecue/Picnic Areas parking lot at 196th Place. Community Center PARK Summer Day Camp **IF PARKING LOT ON 196TH PLACE & UNION TURNPIKE IS FULL-** Here is a list of some of the yearly events at Cunningham Park- Make a right turn at lot exit back onto Union Turn- pike. Make right turn onto Francis Lewis Boulevard, Big Apple Circus (May 16 to May 31) then make the next right turn back into the back of www.bigapplecircus.org the park. Follow the park road to the top of the hill and look for parking lot on your right side. USMC Aviation Demo- Moved to Flushing Meadow Park for 2009 Metropolitan Opera BY PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION- NO SHOW IN 2009 New York Philharmonic Q46 BUS- NO SHOW IN 2009 Friends of Cunningham Park Music Concert Bus runs east to west along Union Turnpike. -

Morpace Presentation Template

2017 Off-Cycle CAHPS® Child Medicaid with CCC Survey Summary Report Centene - NE (Nebraska Total Care) December 2017 Morpace research is completed in compliance with ISO 20252 Table of Contents Executive Highlights . 3 Background, Protocol and Sample . 4 Population Details . .. 5 Disposition Summary and Response Rate . 6 Summary of Key Measure . 7 Comparison to Quality Compass® . 8 Accreditation Details . 10 Key Driver Analysis and Action Plans . 12 Demographics . 25 Supplemental Questions . 29 *Detailed exhibits and data tables available in online reporting portal. 2017 CAHPS® 5.0H Child Medicaid with CCC Survey Centene - NE (Nebraska Total Care) M170182 December 2017 2 2017 Executive Highlights Summary Rate Scores (% Positive Response) 2017 NCQA Accreditation CAHPS Points 2017 Score Approx. 2017 2017 2016 Difference COMPOSITE SCORES 2017 2016 versus 2017 Percentile Approx. Approx. from 2016 Quality Compass Threshold Points Points Getting Care Quickly 92% NA 72nd 75th 1.907 NA NA How Well Doctors Communicate 96% NA 90th NA NA NA NA Care Coordination 83% NA 49th NA NA NA NA Getting Needed Care 87% NA 63rd 50th 1.473 NA NA Customer Service 92% NA 92nd NA NA NA NA Shared Decision Making 84% NA 96th NA NA NA NA OVERALL RATING SCORES Health Care 91% NA 95th 90th 2.167 NA NA Personal Doctor 91% NA 84th 90th 2.167 NA NA Specialist 91% NA 82nd NA NA NA NA Health Plan 86% NA 47th 75th 3.814 NA NA Green (light) shade = relative strength Red (dark) shade = relative weakness 11.528 NA NA Total Possible CAHPS Points = 13.00 Key Learnings from these tables: • The Summary Rate Scores show the proportion of members who rate the plan favorably on a measure - 100% is the highest. -

Waiting and Watching

Waiting and Watching Results of the New York City Transit Riders Council Bus Service and Destination Signage Survey February 2007 Introduction The members of the New York City Transit Riders Council (NYCTRC) maintain a keen interest in bus and subway operations and use both services extensively. Over the years the NYCTRC has conducted several surveys to monitor bus service. The members have conducted these studies in response to bus service that does not adequately serve transit users’ needs. One of the major complaints of bus riders is that they do not find service to be reliable. Many bus riders complain to the Council that a long wait for service, followed by several buses in quick succession, is a frequent experience. As a result the NYCTRC addressed the problems of bus bunching and unacceptable waiting times between buses in this project. In this survey, the Council members collected arrival and departure times for each bus observed at a survey point. This information allowed us to calculate headways, or the period of time between consecutive buses serving the same route recorded at a given point, for most of the bus runs observed and to make comparisons between actual and scheduled headways. The comparison between actual and scheduled headways was used as an indicator of correct spacing of buses. This indicator is different from a measure of schedule adherence, in which we would have collected run numbers of buses observed and matched them to schedule information. We chose to use the headway comparison rather than schedule adherence in our analysis because riders are primarily concerned with having a bus available at a stop within a given period of time and are less concerned whether a particular bus is operating according to its schedule.