Global Urban Indicators Database Version 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPAU HDI Comparative Assessment Technical Note December 2011 Docx

Economic and Policy Analysis Unit UNDP Maputo December 2011 Mozambique’s Performance in the HDI . A comparative Assessment Author: Thomas Kring Technical Note Mozambique’s Performance in the HDI Published by The Economic and Policy Analysis Unit (EPAU) UNDP Mozambique Av. Kenneth Kaunda 931 Maputo, Mozambique Technical Notes from EPAU are intended to be informal notes on economic and technical issues relevant for the work of the UNDP in Mozambique. The views expressed are those of the author and may not be attributed to the UNDP. 1 Technical Note Mozambique’s Performance in the HDI Introduction Since 1990 the UNDP has published the Human Development Report (HDR) on an annual basis. One significant component of the HDR has traditionally been advanced statistics seeking to measure economic and human development in more comprehensive and informative ways. One of the best known measures in the HDR is the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI provides a broad overview of human progress and the complex relationship between income and well-being. The HDI looks beyond the GDP to a broader definition of well-being by including health and knowledge. By doing so it corrects, to some extent, for the inherent weaknesses in traditional measurements of growth and wealth (see Annex 2 for more detail). The recently released Global HDR 2011 provides, as in previous years, a HDI value for a 187 countries in the world. Mozambique’s performance this year, as in previous years, continues to baffle observers. The country has made significant progress in the past ten years or more. It is among the five highest performers in the world measured in terms of average annual increase in the HDI since 2000 in relative terms, and among the top 25 in absolute terms (see Annex 1). -

Ethnolinguistic Diversity and Education. a Successful Pairing

sustainability Article Ethnolinguistic Diversity and Education. A Successful Pairing Mª Ángeles Caraballo 1,* and Eva Mª Buitrago 2 1 Dpto. Economía e Historia Económica and IUSEN, Universidad de Sevilla, 41018 Sevilla, Spain 2 Dpto. Economía Aplicada III and IAIIT, Universidad de Sevilla, 41018 Sevilla, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-954-557-535 Received: 22 October 2019; Accepted: 19 November 2019; Published: 23 November 2019 Abstract: The many growing migratory flows render our societies increasingly heterogeneous. From the point of view of social welfare, achieving all the positive effects of diversity appears as a challenge for our societies. Nevertheless, while it is true that ethnolinguistic diversity involves costs and benefits, at a country level it seems that the former are greater than the latter, even more so when income inequality between ethnic groups is taken into account. In this respect, there is a vast literature at a macro level that shows that ethnolinguistic fragmentation induces lower income, which leads to the conclusion that part of the difference in income observed between countries can be attributed to their different levels of fragmentation. This paper presents primary evidence of the role of education in mitigating the adverse effects of ethnolinguistic fractionalization on the level of income. While the results show a negative association between fragmentation and income for all indices of diversity, the attainment of a certain level of education, especially secondary and tertiary, manages to reverse the sign of the marginal effect of ethnolinguistic fractionalization on income level. Since current societies are increasingly diverse, these results could have major economic policy implications. -

The Human Development Index (HDI) Has Been Criticized for Not Incorporating Distributional Issues

Using Census Data to Explore the Spatial Distribution of Human Development Iñaki Permanyer1 Abstract: The human development index (HDI) has been criticized for not incorporating distributional issues. We propose using census data to construct a municipal-based HDI that allows exploring the distribution of human development with unprecedented geographical coverage and detail. Moreover, we present a new methodology that allows decomposing overall human development inequality according to the contribution of its subcomponents. We illustrate our methodology for Mexico‘s last three census rounds. Municipal-based human development has increased over time and inequality between municipalities has decreased. The wealth component has increasingly accounted for most of the existing inequality in human development during the last twenty years. Keywords: Human Development Index, Measurement, Spatial Distribution, Inequality, Census, Mexico. 1 Contact person: [email protected], +345813060, Centre d‘Estudis Demogràfics, Campus UAB, Bellaterra, 08193, Barcelona, Spain. 1 1. INTRODUCTION Since it was first introduced in the 1990 Human Development Report, the Human Development Index (HDI) has attracted a great deal of interest in policy-making and academic circles alike. As stated in Klugman et al (2011): ―Its popularity can be attributed to the simplicity of its characterization of development – an average of achievements in health, education and income – and to its underlying message that development is much more than economic growth‖. Despite its acknowledged shortcomings (see Kelley 1991, McGillivray 1991, Srinivasan 1994), the HDI has been very helpful to widen the perspective with which academics and policy-makers alike approached the problem of measuring countries development levels (see Herrero et al 2010). -

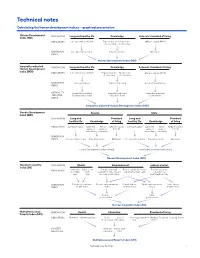

Technical Notes

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female -

The US Education Innovation Index Prototype and Report

SEPTEMBER 2016 The US Education Innovation Index Prototype and Report Jason Weeby, Kelly Robson, and George Mu IDEAS | PEOPLE | RESULTS Table of Contents Introduction 4 Part One: A Measurement Tool for a Dynamic New Sector 6 Looking for Alternatives to a Beleaguered System 7 What Education Can Learn from Other Sectors 13 What Is an Index and Why Use One? 16 US Education Innovation Index Framework 18 The Future of US Education Innovation Index 30 Part Two: Results and Analysis 31 Putting the Index Prototype to the Test 32 How to Interpret USEII Results 34 Indianapolis: The Midwest Deviant 37 New Orleans: Education’s Grand Experiment 46 San Francisco: A Traditional District in an Innovation Hot Spot 55 Kansas City: Murmurs in the Heart of America 63 City Comparisons 71 Table of Contents (Continued) Appendices 75 Appendix A: Methodology 76 Appendix B: Indicator Rationales 84 Appendix C: Data Sources 87 Appendix D: Indicator Wish List 90 Acknowledgments 91 About the Authors 92 About Bellwether Education Partners 92 Endnotes 93 Introduction nnovation is critical to the advancement of any sector. It increases the productivity of firms and provides stakeholders with new choices. Innovation-driven economies I push the boundaries of the technological frontier and successfully exploit opportunities in new markets. This makes innovation a critical element to the competitiveness of advanced economies.1 Innovation is essential in the education sector too. To reverse the trend of widening achievement gaps, we’ll need new and improved education opportunities—alternatives to the centuries-old model for delivering education that underperforms for millions of high- need students. -

2014 Mastercard African Cities Growth Index Understanding Inclusive Urbanization

Knowledge Leadership 2014 MasterCard African Cities Growth Index Understanding Inclusive Urbanization By Dr Yuwa Hendrick-Wong & Professor George Angelopulo Acknowledgements The authors thank Rodger George (Deloitte Consulting (PTY) LTD.) for his advice when designing the MasterCard African Cities Growth Index and Desmond Choong (The Quiet Analyst LTD.) for technical support during data gathering and analysis. Copyright MasterCard 2014 Table of Contents Foreword 4 Introduction 5 ONE | ABOUT THE 2014 MASTERCARD AFRICAN CITIES GROWTH INDEX 7 TWO | THE CITIES OF THE 2014 INDEX 8 Illustration 2.1: The six international comparison cities of the 2014 MasterCard African Cities Growth Index 8 Illustration 2.2: The 74 African cities reviewed by the 2014 MasterCard African Cities Growth Index 9 THREE | DATA AND RANKING 10 Lagging Indicators 10 Illustration 3.1: Lagging indicators 10 Figure 3.1: Lagging indicator ranking by city 12 Leading Indicators 13 Illustration 3.2: Leading indicators 13 Figure 3.2: Leading indicator ranking by city 14 FOUR | CITY RANKING 15 International Comparison Cities 15 Table 4.1: International comparison cities 15 Figure 4.1: Inclusive growth potential - comparison city array 16 Large Cities 17 Table 4.2: Large cities of more than 1 000 000 inhabitants 18 Figure 4.2: Inclusive growth potential - large city array 19 Figure 4.3: 2014 MasterCard African Cities Growth Index - large cities by rank 20 Medium Cities 21 Table 4.3: Medium cities of 500 000 to 1 000 000 inhabitants 21 Figure 4.4: Inclusive growth potential - medium -

Completing the Fertility Transition: Third Birth Developments by Language Groups in Turkey

Demographic Research a free, expedited, online journal of peer-reviewed research and commentary in the population sciences published by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Konrad-Zuse Str. 1, D-18057 Rostock · GERMANY www.demographic-research.org DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 15, ARTICLE 15, PAGES 435-460 PUBLISHED 24 NOVEMBER 2006 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol15/15/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2006.15.15 Research Article Completing the fertility transition: Third birth developments by language groups in Turkey Sutay Yavuz © 2006 Yavuz This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 2.0 Germany, which permits use, reproduction & distribution in any medium for non-commercial purposes, provided the original author(s) and source are given credit. See http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/de/ Table of Contents 1 Introduction 436 2 Background: General fertility trends in Turkey 437 3 Data, methodology, and variables 439 4 Third birth developments in Turkey 446 5 Conclusions 452 6 Acknowledgements 454 References 455 Appendix Tables 458 Demographic Research: Volume 15, Article 15 research article Completing the fertility transition: Third birth developments by language groups in Turkey Sutay Yavuz 1 Abstract The purpose of the present study is to examine third birth dynamics by mother tongue group in Turkey, a country that has reached the advanced stage of its fertility transition. Third-birth intensities of Turkish speaking mothers are lower than Kurdish speaking mothers and the decline in fertility started much later for the latter group. Kurdish speaking women who cannot read and who live in more customary marriages have the highest third birth risk. -

National Strategic Plan for Pre-University Education Reform in Egypt

National Strategic Plan For Pre-University Education Reform In Egypt 2007/08 – 2011/12 Excerpts from The Speech of H.E. President Mohammad Hosni Mubarak on the Occasion of Promulgating Teachers Cadre’s Law 21 June 2007 "Continued reform of our educational system is indeed a major and timely prerequisite for Egypt’s development. All our policies and endeavors have to envision the Egyptian citizen, being the engine and ultimate goal of our national development." "Quality improvement is the most pressing challenge to our national action in its entirety. It even goes beyond the quality of education to cover all the other aspects of performance." "We will take further steps to expand access to basic education and upgrade its quality. These include, but are not limited to, the development of technical education and vocational training centers, promotion of Public- Private Partnerships, and involvement of the civil society in the educational sector. We will also enlarge the scope of decentralization in managing the educational process at governorate-level and beyond; and we believe that we are taking the right way towards goal attainment." Preface by His Excellency Prof. Dr. Yousry El Gamal Minister of Education One crucial reality in Egypt is the firm belief of the political leadership that education is a democratic human right for all the Egyptian citizenry; and that it is the gateway to progress, engine of development, and instrument for the state to improve the quality of life for the entire society. This reality manifests itself in a set of important historical documents which constitute the foundation of any genuine national action to reform education in Egypt. -

Annex D. Comparative Indicators on Evaluation and Assessment

ANNEX D – 151 Annex D. Comparative indicators on evaluation and assessment New Country New Zealand Average1 Zealand’s Rank2 EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT Source: Education at a Glance (OECD, 2010a)3 % of population that has attained at least upper secondary education, by age group (excluding ISCED 3C short programmes)4 (2008) Ages 25-64 72 71 16/30 Ages 25-34 79 80 =21/30 Ages 35-44 74 75 =19/30 Ages 45-54 71 68 =11/30 Ages 55-64 62 58 =13/30 % of population that has attained tertiary education, by age group (2008) Ages 25-64 40 28 4/31 Ages 25-34 48 35 4/31 Ages 35-44 40 29 6/31 Ages 45-54 38 25 4/31 Ages 55-64 34 20 3/31 Upper secondary graduation rates (2008) % of upper secondary graduates (first-time graduation) to the population at the typical 78 80 =16/26 age of graduation STUDENT PERFORMANCE Mean performance in PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) (15-year-olds) Source: PISA 2009 Results (OECD, 2010d)3 Reading literacy 521 493 4/34 Mathematics literacy 519 496 7/34 Science literacy 532 501 4/34 SCHOOL SYSTEM EXPENDITURE Source: Education at a Glance (OECD, 2010a)3 Expenditure on primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary institutions as a % of GDP, from public and private sources 1995 m ~ m 2000 m ~ m 2007 4.0 3.6 6/29 Public expenditure on primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary 11.7 9.0 4/29 education as a % of total public expenditure (2008)5 Total expenditure on primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary 85.6 90.3 20/25 education from public sources (2007) (%) Annual expenditure per student -

Social Progress Index 2014

SOCIAL PROGRESS INDEX 2014 BY MICHAEL E. PORTER AND SCOTT STERN WITH MICHAEL GREEN The Social Progress Imperative is registered as a nonprofit organization in the United States. We are grateful to the following organizations for their financial support: SOCIAL PROGRESS INDEX 2014 FOREWORD ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..9 CHAPTER 1 / THE URGENT NEED TO MEASURE SOCIAL PROGRESS ……………………………………21 CHAPTER 2 / SOCIAL PROGRESS INDEX 2014 RESULTS ………………………………………………………39 CHAPTER 3 / CASE STUDIES ……………………………………………………………………………………………………..73 APPENDIX 1 / 2014 SOCIAL PROGRESS INDEX 2014 FULL RESULTS ……………………………………86 APPENDIX 2 / SCORECARD SUMMARY ……………………………………………………………………………………92 APPENDIX 3 / INDICATOR DEFINITIONS AND SOURCES ………………………………………………………95 APPENDIX 4 / DATA GAPS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………111 Social Progress Index 2014 1 FOREWORD/ BRIZIO BIONDI-MORRA We at the Social Progress Imperative want to see social progress used alongside GDP per capita as a key measure of the success of a country. By reframing how the world measures success, putting the real things that matter to people’s lives at the top of the agenda, we believe that governments, businesses and civil society organizations can make better choices. This is a bold vision. Yet that boldness, or maybe audacity, is what the world needs. Our generation is wrestling with the need to offer better lives to a world population that is not just growing but ageing too. Economic growth has brought many benefits but we are hitting environmental limits and social indicators lag too slowly behind. We live in a world on the cusp of different challenges: too many people under-nourished and too many risking early death and disability from obesity. Old models based on a rich ‘North’ and a poor ‘South’ make less and less sense. -

Republic of Mozambique Study for Poverty Profile (Africa) Final Report

Republic of Mozambique Study for Poverty Profile (Africa) Final Report March 2011 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting Co. Ltd. POVERTY INDEX Basic data Population, Population GDP, PPP GDP per GDP Year total growth (billion capita PPP growth (million) (annual) US$) (US$) (annual) Mozambique 2008 20.747 2.7 18.3 885.2 6.8 Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database April 2010 Population growth rate is data in 2007. Source: MPD (2010) “Understanding Poverty and Well-being Mozambique: Third National Poverty Assessment" GDP growth rate data in 2009 Source: Republic of Mozambique (2010) "Report on the Development Goals" Poverty Inequality Poverty Incidence (%) Poverty Gap Survey Gini Source Year National Urban Rural Index Year Coefficient (national) POVERTY AND WELLBEING IN MOZAMBIQUE: 54.7 49.6 56.9 21.2 2008/09 0.414 2008/09 THIRD NATIONAL POVERTY ASSESSMENT Source: Third National Poverty Assessment (2010) NATIONAL MAP TANZANIA ZAMBIA Carbo Delgado NIassa MALAWI Nampula Tete Zambezi MOZAMBIQUE Manica ZIMBABWE Sofara Inhambane Gaza SOUTH AFRICA Maputo Maputo CIty SWAZILAND Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs "aid program according to Mozambique" SOCIAL INDICATOR MAP POVERTY RATE Incidence of poverty by province in 2009 in Mozambique Legend 50% or less 50% - 70% Not less than 70% National Average: 54.7% (2009) Source: UNDP (2010) Report on the Millennium Development Goals SCHOOL ATTENDANCE by province [6 to 12 years olds] Net EP enrolment rate for 6-12 year old children, by province in 2008 -

Social Progress Index 2017

SOCIAL PROGRESS INDEX 2017 BY MICHAEL E. PORTER AND SCOTT STERN SOCIAL WITH MICHAEL GREEN PROGRESS IMPERATIVE SOCIAL PROGRESS INDEX 2017 CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Chapter 1 / Why We Measure Social Progress 10 Chapter 2 / How We Measure Social Progress 14 Chapter 3 / 2017 Social Progress Index Results 22 Chapter 4 / Global Trends in Social Progress, 2014–2017 39 Supplemental Section / From Index to Action to Impact 55 Appendix A / Definitions and Data Sources 68 Appendix B / 2017 Social Progress Index Full Results 74 Appendix C / Social Progress Index vs Log of GDP Per Capita 79 Appendix D / Country Scorecard Summary 80 Acknowledgments 84 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2017 SOCIAL PROGRESS INDEX Social progress has become an increasingly critical on average, personal security is no better in middle- agenda for leaders in government, business, and income countries than low-income ones, and is often civil society. Citizens’ demands for better lives are worse. Too many people — regardless of income — evident in uprisings such as the Arab Spring and the live without full rights and experience discrimination emergence of new political movements in even the or even violence based on gender, religion, ethnicity, most prosperous countries, such as the United States or sexual orientation. and France. Since the financial crisis of 2008, citizens are increasingly expecting that business play its role Traditional measures of national income, such as in delivering improvements in the lives of customers GDP per capita, fail to capture the overall progress of and employees, and protecting the environment for societies. us all. This is the social progress imperative.