Bunia Swahili and Emblematic Language Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ituri:Stakes, Actors, Dynamics

ITURI STAKES, ACTORS, DYNAMICS FEWER/AIP/APFO/CSVR would like to stress that this report is based on the situation observed and information collected between March and August 2003, mainly in Ituri and Kinshasa. The 'current' situation therefore refers to the circumstances that prevailed as of August 2003, when the mission last visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Swedish International Development Agency. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish Government and its agencies. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Department for Development Policy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Finnish Government and its agencies. Copyright 2003 © Africa Initiative Program (AIP) Africa Peace Forum (APFO) Centre for Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Forum on Early Warning and Early Response (FEWER) The views expressed by participants in the workshop are not necessarily those held by the workshop organisers and can in no way be take to reflect the views of AIP, APFO, CSVR and FEWER as organisations. 2 List of Acronyms............................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................................................... -

Addressing Root Causes of Conflict: a Case Study Of

Experience paper Addressing root causes of conflict: A case study of the International Security and Stabilization Support Strategy and the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI) in Ituri Province, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo Oslo, May 2019 1 About the Author: Ingebjørg Finnbakk has been deployed by the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) to the Stabilization Support Unit (SSU) in MONUSCO from August 2016 until February 2019. Together with SSU Headquarters and Congolese partners she has been a key actor in developing and implementing the ISSSS program in Ituri Province, leading to a joint MONUSCO and Government process and strategy aimed at demobilizing a 20-year-old armed group in Ituri, the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI). The views expressed in this report are her own, and do not represent those of either the UN or the Norwegian Refugee Council/NORDEM. About NORDEM: The Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) is NORCAP’s civilian capacity provider specializing in human rights and support for democracy. NORDEM has supported the SSU with personnel since 2013, hence contribution significantly with staff through the various preparatory phases as well as during the implementation. Acknowledgements: Reaching the point of implementing ISSSS phase two programs has required a lot of analyses, planning and stakeholder engagement. The work presented in this report would not be possible without all the efforts of previous SSU staff under the leadership of Richard de La Falaise. The FRPI process would not have been possible without the support and visions from Francois van Lierde (deployed by NORDEM) and Frances Charles at SSU HQ level. -

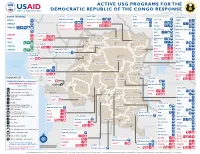

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

Justice - Plus

JUSTICE - PLUS PANEL OF RESEARCH ON THE PROLIFERATION AND ILLICIT TRAFFIC OF SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS IN THE FRONTIER AREAS BETWEEN SUDAN, UGANDA AND THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO PROLIFERATION AND ILLICIT TRAFFIC OF SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS IN THE NORTH EAST OF THE DRC Summary Report by Flory KAYEMBE SHAMBA Désiré NKOY ELELA Missak KASONGO MUZEU Kinshasa, January 2003 JUSTICE-PLUS • BUNIA • KINSHASA Siège social Bureau de liaison 39bis, Av. KASAVUBU,Q. Lumumba 3, Av. KITONA, Q. Righini, C/Lemba B.P 630-BUNIA B.P. 2063 Kinshasa 1 Tél. : (+) 871762568941 tél. : (+)243 98171 100 Fax : (+)871762568943 Fax : (+) 243 8801826 E-mail : [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] research on the proliferation and illicit traffic of small arms and light weapons in the north east of the drc – flodémis 1 _______________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS INITIALS……..…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………….……………………………………………………………… 3 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 I. CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK …………………………..………….. 6 TERMES DE REFERENCE……………………………………………………………………… 6 METHODOLOGY AND UNFOLDING OF THE RESEARCH……………………………. 9 II. OUTLINE OF THE SITUATION IN THE NORTH EAST OF THE DRC ………………….. 10 MAPPING OF CONFLITS IN ITURI AND UPPER UELE (Alliances and counter-alliances)…………………………………………………………..…….. 12 III. PRESENTATION OF DATE BY INVESTIGATION CENTRE………………………………… 13 IV. SUMMARY OF RESEARCH FINDINGS ……………………..……………………………….… 14 4.1. GENERAL PERCEPTION OF THE CONFLITS ……………………………………... 14 4.2. SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS : CIRCUITS OF ACQUISITION, COST, SOURCES OF SUPPLY, COMMERCIAL FLOW, IMPORTANCE …………………………………………………………………………….. 17 4.3. CONTROL OF THE CIRCULATION OF SMALL ARMS & LIGHT WEAPONS AND PROSPECTS FOR PEACE IN AFRICA’S GREAT LAKES REGION …………… 20 4.4. VERIFICATION OF RESEARCH HYPOTHESES ……………………………..…… 23 V. STRATEGIES OF FIGHT AND RECOMMENDATIONS ………………………………………… 26 5.1. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Gis Unit, Monuc Africa

Map No.SP. 103 ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO GIS UNIT, MONUC AFRICA 12°30'0"E 15°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E Central African Republic N N " " 0 0 ' Sudan ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 Z o n g oBangui Mobayi Bosobolo Gbadolite Yakoma Ango Yaounde Bondo Nord Ubangi Niangara Faradje Cameroon Libenge Bas Uele Dungu Bambesa Businga G e m e n a Haut Uele Poko Rungu Watsa Sud Ubangi Aru Aketi B u tt a II s ii rr o r e Kungu Budjala v N i N " R " 0 0 ' i ' g 0 n 0 3 a 3 ° b Mahagi ° 2 U L ii s a ll a Bumba Wamba 2 Orientale Mongala Co Djugu ng o R i Makanza v Banalia B u n ii a Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo MambasaIturi B a s a n k u s u Basoko Yahuma Bafwasende Equateur Isangi Djolu Yangambi K i s a n g a n i Bolomba Befale Tshopa K i s a n g a n i Beni Uganda M b a n d a k a N N " Equateur " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Lubero ° 0 Ingende B o e n d e 0 Gabon Ubundu Lake Edward Opala Bikoro Bokungu Lubutu North Kivu Congo Tshuapa Lukolela Ikela Rutshuru Kiri Punia Walikale Masisi Monkoto G o m a Yumbi II n o n g o Kigali Bolobo Lake Kivu Rwanda Lomela Kalehe S S " KabareB u k a v u " 0 0 ' ' 0 Kailo Walungu 0 3 3 ° Shabunda ° 2 2 Mai Ndombe K ii n d u Mushie Mwenga Kwamouth Maniema Pangi B a n d u n d u Bujumbura Oshwe Katako-Kombe South Kivu Uvira Dekese Kole Sankuru Burundi Kas ai R Bagata iver Kibombo Brazzaville Ilebo Fizi Kinshasa Kasongo KasanguluKinshasa Bandundu Bulungu Kasai Oriental Kabambare K e n g e Mweka Lubefu S Luozi L u s a m b o S " Tshela Madimba Kwilu Kasai -

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule Effective from 09th June 2021 AIRCRAFT MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:00 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:30 KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 08:45 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 UNO-234H 09:30 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 10:55 10:00 MBANDAKA YAKOMA 11:40 09:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 11:00 10:00 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 11:25 10:00 MBANDAKA LIBENGE 11:00 5Y-VVI 11:25 GBADOLITE BANGUI 12:10 12:10 YAKOMA MBANDAKA 13:50 11:30 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 12:00 11:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 13:20 11:30 LIBENGE BANGUI 11:50 DHC-8-Q400 13:00 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:20 14:20 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:50 12:30 IMPFONDO MBANDAKA 13:00 13:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:20 12:40 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE 14:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:20 13:30 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 15:00 14:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:00 15:30 BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 15:45 AD HOC CARGO FLIGHT TSA WITH UNHCR KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 08:00 KINSHASA KALEMIE 11:15 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 UNO-207H 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 11:45 KALEMIE GOMA 12:35 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 5Y-CRZ SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE EMB-145 LR 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 13:35 GOMA KINSHASA 14:50 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 -

Laboratory Phonology 7

Laboratory Phonology 7 ≥ Phonology and Phonetics 4-1 Editor Aditi Lahiri Mouton de Gruyter Berlin · New York Laboratory Phonology 7 edited by Carlos Gussenhoven Natasha Warner Mouton de Gruyter Berlin · New York 2002 Mouton de Gruyter (formerly Mouton, The Hague) is a Division of Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin. Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper which falls within the guidelines of the ANSI to ensure permanence and durability. Die Deutsche Bibliothek Ϫ Cataloging-in-Publication Data Laboratory phonology / ed. by Carlos Gussenhoven ; Natasha Warner. Ϫ Berlin ; New York : Mouton de Gruyter, 7. Ϫ (2002) (Phonology and phonetics ; 4,1) ISBN 3-11-017086-8 ISBN 3-11-017087-6 Ą Copyright 2002 by Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, D-10785 Berlin. All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printing & Binding: Hubert & Co., Göttingen Cover design: Christopher Schneider, Berlin. Printed in Germany. Table of Contents List of authors ix Acknowledgements xi Introduction xiii Carlos Gussenhoven & Natasha Warner Part 1: Phonological Processing and Encoding 1 The role of the lemma in form variation 3 Daniel Jurafsky, Alan Bell & Cynthia Girand Phonological encoding of single words: In search of the 35 lost syllable Niels O. Schiller, Albert Costa & Angels Colome´ Temporal distribution of interrogativity markers in Dutch: 61 A perceptual study Vincent J. van Heuven & Judith Haan Phonological Encoding in speech production: Comments 87 on Jurafsky et al., Schiller et al., and van Heuven & Haan Willem P. -

Intersectionality and International Law: Recognizing Complex Identities on the Global Stage

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLH\28-1\HLH105.txt unknown Seq: 1 6-JUL-15 11:18 Intersectionality and International Law: Recognizing Complex Identities on the Global Stage Aisha Nicole Davis* As a legal theory, intersectionality seeks to create frameworks that con- sider the multiple identities that individuals possess, including race, gen- der, sexuality, age, and ability. When applied, intersectionality recognizes complexities in an individual’s identity to an extent not possi- ble using mechanisms that focus solely on one minority marker. This Note proposes incorporating intersectional consideration in the realm of inter- national human rights law and international humanitarian law to bet- ter address the human rights violations that affect women whose identities fall within more than one minority group because of their ethnicity or race. The Note begins with an explanation of intersectional- ity, and then applies intersectionality to human rights mechanisms within the United Nations and to cases in international criminal tribu- nals and the International Criminal Court. As it stands, international human rights law, international criminal law, and international hu- manitarian law view women who are members of a racial or ethnic mi- nority as variants on a given category. This Note contends that by applying a framework that further incorporates intersectionality—that is, both in discourse and action—in international human rights law, international humanitarian law, and international criminal law, these women’s identities will be more fully recognized, opening up the possibil- ity for more representative women’s rights discourse, and remedies for human rights abuses that better address the scope and nature of the violations. -

THE COMPLEXITY of ETHNIC CONFLICT Hema and Lendu Case Study

THE COMPLEXITY OF ETHNIC CONFLICT Hema and Lendu Case Study Nelson Tusiime 960816-1411 International migration and Ethnic Relations Bachelor Thesis Course code: IM245L 15 Credits Spring 2019 Supervisor: Beint Magnus Aamodt Bentsen Word Count: 12,141 2 Nelson Tusiime IMER Bachelor Thesis 2019 Spring Abstract This research paper investigated the Hema and Lendu conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo from 1999-2003. Five significant theories; Primordialism, constructivism, instrumen- talism, greed and grievances were applied to explain the causes of this conflict and to find out the role ethnicity played in triggering the conflict. Using secondary data, a single-case study was conducted, and results show that colonialism, inequality, poor government policies, greed from local and external forces are the primary causes of this conflict. Based on the results, one theory on its own is not substantial enough to explain the cause of this conflict since it was triggered by a combination of different factors. However, the Hema and Lendu did not fight because of their ethnic differences. Ethnicity was used by militia leaders as a tool for mobili- sation thus ethnicity being a secondary factor and not a driving force. Therefore, ethnicity did not play a significant role in triggering this conflict. Keywords: Ethnicity, Ethnic Conflict, Hema, Lendu, DR. Congo, 3 Nelson Tusiime IMER Bachelor Thesis 2019 Spring Table of Contents List of Acronyms ..................................................................................................................... -

Towards a Spirituality of Reconciliation with Special Reference to the Lendu and Hema People in the Diocese of Bunia (Democratic Republic of Congo) Alfred Ndrabu Buju

Towards a spirituality of reconciliation with special reference to the Lendu and Hema people in the diocese of Bunia (Democratic Republic of Congo) Alfred Ndrabu Buju To cite this version: Alfred Ndrabu Buju. Towards a spirituality of reconciliation with special reference to the Lendu and Hema people in the diocese of Bunia (Democratic Republic of Congo). Religions. 2002. dumas- 01295025 HAL Id: dumas-01295025 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01295025 Submitted on 30 Mar 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF EASTERN AFRICA FACULTY OF THEOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF SPIRITUAL THEOLOGY TOWARDS A SI'IRITUALITY OF RECONCILIATION WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE LENDU AND IIEMA PEOPLE IN THE DIOCESE OF BUNIA / DRC IFRA 111111111111 111111111111111111 I F RA001643 o o 3 j)'VA Lr .2 8 A Thesis Sulimitted to the Catholic University of Eastern Africa in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Licentiate Degree in Spiritual Theology By Rev. Fr. Ndrabu 13itju Alfred May 2002 tt. it Y 1 , JJ Nairobi-ken;• _ .../i"; .1 tic? ‘vii-.11:3! ..y/ror/tro DECLARATION THE CATIIOLIC UNIVERSITY OF EASTERN AFRICA Thesis Title: TOWARDS A SPIRITUALITY OF RECONCILIATION WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO LENDU AND IIEMA PEOPLE IN TIIE DIOCESE OF BUNIA/DRC By Rev. -

Download/Speech%20Moreno.Pdf> Accessed September 10, 2013

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Ruhweza, Daniel Ronald (2016) Situating the Place for Traditional Justice Mechanisms in International Criminal Justice: A Critical Analysis of the implications of the Juba Peace Agreement on Reconciliation and Accountability. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/56646/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Situating the Place for Traditional Justice Mechanisms in International Criminal Justice: A Critical Analysis of the implications of the Juba Peace Agreement on Reconciliation and Accountability By DANIEL RONALD RUHWEZA Supervised by Dr. Emily Haslam, Prof. Toni Williams & Prof. Wade Mansell A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Award of the Doctor of Philosophy in Law (International Criminal Law) at University of Kent at Canterbury April 2016 DECLARATION I declare that the thesis I have presented for examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Kent at Canterbury is exclusively my own work other than where I have evidently specified that it is the work of other people.