Balserak, J. (2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metos, Merik the Vanishing Pope.Pdf

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY THE VANISHING POPE MERIK HUNTER METOS SPRING 2009 ADVISOR: DR. SPOHNHOLZ DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS Honors Thesis ************************* PASS WITH DISTINCTION JOSI~~ s eLf" \\)J I \%\1 )10 dW JOJ JOS!Ape S!SalH· S\;/ :383110J S~ONOH A.1IS~31\INn 3H.1 0.1 PRECIS Pope Benoit XIII (1328-1423), although an influential advocate for reforms within the Catholic Church in the middle ages, receives little attention from modem historians. Historians rarely offer more than a brief biography and often neglect to mention at all his key role in the Great Schism. Yet, the very absence ofPope Benoit XIU from most historical narratives of medieval history itself highlights the active role that historians play in determining what gets recorded. In some cases, the choices that people make in determining what does, and what does not, get included in historical accounts reveals as much about the motivations and intentions of the people recording that past as it does about their subjects. This essay studies one example of this problem, in this case Europeans during the Reformation era who self-consciously manipulated sources from medieval history to promote their own agendas. We can see this in the sixteenth-century translation ofa treatise written by the medieval theologian Nicholas de Clamanges (1363-1437. Clamanges was a university professor and served as Benoit XIII's secretary during the Great Schism in Avignon, France. The treatise, entitled La Traite de fa Ruine de f'Eglise, was written in Latin in 1398 and was first distributed after Clamanges' death in 1437. -

The Theology of the French Reformed Churches Martin I

The Theology of the French Reformed Churches REFORMED HISTORICAL-THEOLOGICAL STUDIES General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Jay T. Collier BOOKS IN SERIES: The Christology of John Owen Richard W. Daniels The Covenant Theology of Caspar Olevianus Lyle D. Bierma John Diodati’s Doctrine of Holy Scripture Andrea Ferrari Caspar Olevian and the Substance of the Covenant R. Scott Clark Introduction to Reformed Scholasticism Willem J. van Asselt, et al. The Spiritual Brotherhood Paul R. Schaefer Jr. Teaching Predestination David H. Kranendonk The Marrow Controversy and Seceder Tradition William VanDoodewaard Unity and Continuity in Covenantal Thought Andrew A. Woolsey The Theology of the French Reformed Churches Martin I. Klauber The Theology of the French Reformed Churches: From Henri IV to the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes Edited by Martin I. Klauber Reformation Heritage Books Grand Rapids, Michigan The Theology of the French Reformed Churches © 2014 by Martin I. Klauber All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any man ner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Direct your requests to the publisher at the following address: Reformation Heritage Books 2965 Leonard St. NE Grand Rapids, MI 49525 6169770889 / Fax 6162853246 [email protected] www.heritagebooks.org Printed in the United States of America 14 15 16 17 18 19/10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 [CIP info] For additional Reformed literature, request a free book list from Reformation Heritage Books at the above regular or e-mail address. -

2012 Calvin Bibliography

2012 Calvin Bibliography Compiled by Paul W. Fields and Andrew M. McGinnis (Research Assistant) I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography B. Cultural Context—Intellectual History C. Cultural Context—Social History D. Friends E. Polemical Relationships II. Calvin’s Works A. Works and Selections B. Criticism and Interpretation III. Calvin’s Theology A. Overview B. Revelation 1. Scripture 2. Exegesis and Hermeneutics C. Doctrine of God 1. Overview 2. Creation 3. Knowledge of God 4. Providence 5. Trinity D. Doctrine of Christ E. Doctrine of the Holy Spirit F. Doctrine of Humanity 1. Overview 2. Covenant 3. Ethics 4. Free Will 5. Grace 6. Image of God 7. Natural Law 8. Sin G. Doctrine of Salvation 1. Assurance 2. Atonement 1 3. Faith 4. Justification 5. Predestination 6. Sanctification 7. Union with Christ H. Doctrine of the Christian Life 1. Overview 2. Piety 3. Prayer I. Ecclesiology 1. Overview 2. Discipline 3. Instruction 4. Judaism 5. Missions 6. Polity J. Worship 1. Overview 2. Images 3. Liturgy 4. Music 5. Preaching 6. Sacraments IV. Calvin and Social-Ethical Issues V. Calvin and Economic and Political Issues VI. Calvinism A. Theological Influence 1. Overview 2. Christian Life 3. Church Discipline 4. Ecclesiology 5. Holy Spirit 6. Predestination 7. Salvation 8. Worship B. Cultural Influence 1. Arts 2. Cultural Context—Intellectual History 2 3. Cultural Context—Social History 4. Education 5. Literature C. Social, Economic, and Political Influence D. International Influence 1. Australia 2. Eastern Europe 3. England 4. Europe 5. France 6. Geneva 7. Germany 8. Hungary 9. India 10. -

Introduction

Introduction The Other Voice [Monsieur de Voysenon] told [the soldiers] that in the past he had known me to be a good Catholic, but that he could not say whether or not I had remained that way. At that mo- ment arrived an honorable woman who asked them what they wanted to do with me; they told her, “By God, she is a Huguenot who ought to be drowned.” Charlotte Arbaleste Duplessis-Mornay, Memoirs The judge was talking about the people who had been ar- rested and the sorts of disguises they had used. All of this terrified me. But my fear was far greater when both the priest and the judge turned to me and said, “Here is a little rascal who could easily be a Huguenot.” I was very upset to see myself addressed that way. However, I responded with as much firmness as I could, “I can assure you, sir, that I am as much a Catholic as I am a boy.” Anne Marguerite Petit Du Noyer, Memoirs The cover of this book depicting Protestantism as a woman attacked on all sides reproduces the engraving that appears on the frontispiece of the first volume of Élie Benoist’s History of the Edict of Nantes.1 This illustration serves well Benoist’s purpose in writing his massive work, which was to protest both the injustice of revoking an “irrevocable” edict and the oppressive measures accompanying it. It also says much about the Huguenot experience in general, and the experience of Huguenot women in particular. When Benoist undertook the writing of his work, the association between Protestantism and women was not new. -

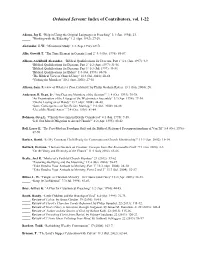

Ordained Servant: Index of Contributors, Vol. 1-22

Ordained Servant: Index of Contributors, vol. 1-22 Adams, Jay E. “Help in Using the Original Languages in Preaching” 3:1 (Jan. 1994): 23. _____. “Working with the Eldership” 1:2 (Apr. 1992): 27-29. Alexander, J. W. “Ministerial Study” 1:3 (Sep. 1992): 69-71. Allis, Oswald T. “The Time Element in Genesis 1 and 2” 4:4 (Oct. 1995): 85-87. Allison, Archibald Alexander. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 1” 6:1 (Jan. 1997): 4-9. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 2” 6:2 (Apr. 1997): 31-36. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 3” 6:3 (Jul. 1997): 49-54. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Elders” 3:4 (Oct. 1994): 80-96. _____. “The Biblical View of Church Unity” 10:3 (Jul. 2001): 60-64. _____. “Visiting the Members” 10:2 (Apr. 2001): 27-30. Allison, Sam. Review of What is a True Calvinist? by Philip Graham Ryken. 13:1 (Jan. 2004): 20. Anderson, R. Dean, Jr. “Are Deacons Members of the Session?” 2: 4 (Oct. 1993): 75-78. _____. “An Examination of the Liturgy of the Westminster Assembly” 3:2 (Apr. 1994): 27-34. _____. “On the Laying on of Hands” 13:2 (Apr. 2004): 44-48. _____. “Some Consequences of Sex Before Marriage” 9:4 (Oct. 2000): 86-88. _____. “Use of the Word ‘Amen’” 7:4 (Oct. 1998): 81-84. Bahnsen, Greg L. “Church Government Briefly Considered” 4:1 (Jan. 1995): 9-10. _____. “Is It Our Moral Obligation to Attend Church?” 4:2 (Apr. 1995): 40-42. Ball, Larry E. “The Post-Modern Paradigm Shift and the Biblical, Reformed Presuppositionalism of Van Til” 5:4 (Oct. -

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France Bethany Hume PhD University of York History September 2019 2 Abstract This thesis responds to the historiographical focus on the trope of the Albigensians and Waldensians within sixteenth-century confessional polemic. It supports a shift away from the consideration of medieval heresy in early modern historical writing merely as literary topoi of the French Wars of Religion. Instead, it argues for a more detailed examination of the medieval heretical and inquisitorial sources used within seventeenth-century French intellectual culture and religious polemic. It does this by examining the context of the Doat Commission (1663-1670), which transcribed a collection of inquisition registers from Languedoc, 1235-44. Jean de Doat (c.1600-1683), President of the Chambre des Comptes of the parlement of Pau from 1646, was charged by royal commission to the south of France to copy documents of interest to the Crown. This thesis aims to explore the Doat Commission within the wider context of ideas on medieval heresy in seventeenth-century France. The periodization “medieval” is extremely broad and incorporates many forms of heresy throughout Europe. As such, the scope of this thesis surveys how thirteenth-century heretics, namely the Albigensians and Waldensians, were portrayed in historical narrative in the 1600s. The field of study that this thesis hopes to contribute to includes the growth of historical interest in medieval heresy and its repression, and the search for original sources by seventeenth-century savants. By exploring the ideas of medieval heresy espoused by different intellectual networks it becomes clear that early modern European thought on medieval heresy informed antiquarianism, historical writing, and ideas of justice and persecution, as well as shaping confessional identity. -

Theology of the Westminster Confession, the Larger Catechism, and The

or centuries, countless Christians have turned to the Westminster Standards for insights into the Christian faith. These renowned documents—first published in the middle of the 17th century—are widely regarded as some of the most beautifully written summaries of the F STANDARDS WESTMINSTER Bible’s teaching ever produced. Church historian John Fesko walks readers through the background and T he theology of the Westminster Confession, the Larger Catechism, and the THEOLOGY The Shorter Catechism, helpfully situating them within their original context. HISTORICAL Organized according to the major categories of systematic theology, this book utilizes quotations from other key works from the same time period CONTEXT to shed light on the history and significance of these influential documents. THEOLOGY & THEOLOGICAL of the INSIGHTS “I picked up this book expecting to find a resource to be consulted, but of the found myself reading the whole work through with rapt attention. There is gold in these hills!” MICHAEL HORTON, J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics, Westminster Seminary California; author, Calvin on the Christian Life WESTMINSTER “This book is a sourcebook par excellence. Fesko helps us understand the Westminster Confession and catechisms not only in their theological context, but also in their relevance for today.” HERMAN SELDERHUIS, Professor of Church History, Theological University of Apeldoorn; FESKO STANDARDS Director, Refo500, The Netherlands “This is an essential volume. It will be a standard work for decades to come.” JAMES M. RENIHAN, Dean and Professor of Historical Theology, Institute of Reformed Baptist Studies J. V. FESKO (PhD, University of Aberdeen) is academic dean and professor of systematic and historical theology at Westminster Seminary California. -

Download- Ed From: Books at JSTOR, EBSCO, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, OAPEN, Project MUSE, and Many Other Open Repositories

’ James B. Collins, Professor of History, Georgetown University Mack P. Holt, Professor of History, George Mason University The Scourge of Demons: Pragmatic Toleration: Possession, Lust, and Witchcra in a The Politics of Religious Heterodoxy in Seventeenth-Century Italian Convent Early Reformation Antwerp, – Jerey R. Watt Victoria Christman Expansion and Crisis in Louis XIV’s Violence and Honor in France: Franche-Comté and Prerevolutionary Périgord Absolute Monarchy, – Steven G. Reinhardt Darryl Dee State Formation in Early Modern Noble Strategies in an Early Modern Alsace, – Small State: The Mahuet of Lorraine Stephen A. Lazer Charles T. Lipp Consuls and Captives: Louis XIV’s Assault on Privilege: Dutch-North African Diplomacy in the Nicolas Desmaretz and the Early Modern Mediterranean Tax on Wealth Erica Heinsen-Roach Gary B. McCollim Gunpowder, Masculinity, and Warfare A Show of Hands for the Republic: in German Texts, – Opinion, Information, and Repression Patrick Brugh in Eighteenth-Century Rural France Jill Maciak Walshaw A complete list of titles in the Changing Perspectives on Early Modern Europe series may be found on our website, www.urpress.com. The Consistory and Social Discipline in Calvin’s Geneva Jerey R. Watt Copyright © by Jerey R. Watt CC BY-NC All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published University of Rochester Press Mt. Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY , USA www.urpress.com and Boydell & Brewer Limited PO Box , Woodbridge, Suolk IP DF, UK www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN-: ---- ISSN: -; vol. -

Calvinism and Religious Toleration in France and The

CALVINISM AND RELIGIOUS TOLERATION IN FRANCE AND THE NETHERLANDS, 1555-1609 by David L. Robinson Bachelor of Arts, Memorial University of Newfoundland (Sir Wilfred Grenfell College), 2011 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: Gary K. Waite, PhD, History Examining Board: Cheryl Fury, PhD, History, UNBSJ Sean Kennedy, PhD, Chair, History Gary K. Waite, PhD, History Joanne Wright, PhD, Political Science This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK May, 2011 ©David L. Robinson, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91828-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91828-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

John Calvin and the Printed Book

Calvin2005 Page i Friday, August 5, 2005 1:43 PM John Calvin and the Printed Book Calvin2005 Page ii Friday, August 5, 2005 1:43 PM Habent sua fata libelli Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series General Editor Raymond A. Mentzer University of Iowa Editorial Board of Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Elaine Beilin Helen Nader Framingham State College University of Arizona Miriam U. Chrisman Charles G. Nauert University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus Barbara B. Diefendorf Theodore K. Rabb Boston University Princeton University Paula Findlen Max Reinhart Stanford University University of Georgia Scott H. Hendrix Sheryl E. Reiss Princeton Theological Seminary Cornell University Jane Campbell Hutchison John D. Roth University of Wisconsin–Madison Goshen College Ralph Keen Robert V. Schnucker University of Iowa Tr uman State University, Emeritus Robert M. Kingdon Nicholas Terpstra University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Toronto Mary B. McKinley Margo Todd University of Virginia University of Pennsylvania Merry Wiesner-Hanks University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee 00PrelimsCalvin Page iv Friday, September 2, 2005 2:02 PM Copyright 2005 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2005. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series tsup.truman.edu Translation of Jean-François Gilmont, Jean Calvin et le livre imprimé, edition published by Droz, 1206 Geneva, Switzerland, © copyright 1997 by Librairie Droz SA. Cover illustration: “Ionnes Calvinus Natus novioduni Picardorum,” in John Calvin, Joannis Calvini Noviodumensis opera omniain novem tomos digesta. Amsterdam: Johann Jacob Schipper, 1667, 1:*4v. Cover and title page design: Teresa Wheeler Type: AGaramond, copyright Adobe Systems Inc. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gilmont, Jean François. -

Letters from the Queen of Navarre with an Ample Declaration

JEANNE D’ALBRET Letters from the Queen of Navarre with an Ample Declaration • Edited and translated by KATHLEEN M. LLEWELLYN, EMILY E. THOMPSON, AND COLETTE H. WINN Iter Academic Press Toronto, Ontario Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies Tempe, Arizona 2016 Iter Academic Press Tel: 416/978–7074 Email: [email protected] Fax: 416/978–1668 Web: www.itergateway.org Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies Tel: 480/965–5900 Email: [email protected] Fax: 480/965–1681 Web: acmrs.org © 2016 Iter, Inc. and the Arizona Board of Regents for Arizona State University. All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jeanne d’Albret, Queen of Navarre, 1528–1572, author. | Llewellyn, Kathleen M., editor and translator. | Thompson, Emily E., editor and translator. | Winn, Colette H., editor and translator. | Jeanne d’Albret, Queen of Navarre, 1528–1572. Ample déclaration. Title: Jeanne d’Albret : letters from the Queen of Navarre with an ample declaration / edited and translated by Kathleen M. Llewellyn, Emily E. Thompson, and Collette H. Winn. Other titles: Correspondence. English. | Ample déclaration. Description: Tempe, Arizona : Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies ; Toronto, Ontario : Iter Academic Press, [2016] | Series: The other voice in early modern Europe ; 43 | Series: Medieval and renaissance texts and studies ; volume 490 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015042129 (print) | LCCN 2015047111 (ebook) | ISBN 9780866985451 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780866987172 () Subjects: LCSH: Jeanne d’Albret, Queen of Navarre, 1528–1572.--Correspondence | Queens--France-- Correspondence. | France--Kings and rulers--Correspondence. | France--History--Charles IX, 1560-1574--Sources. -

Portraits of the Queen Mother: Polemics, Panegyrics, Letters

Portraits of the Queen Mother: Polemics, Panegyrics, Letters CATHERINE DE MÉDICIS AND OTHERS • Translation and study by LEAH L. CHANG AND KATHERINE KONG Iter Inc. Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Toronto 2014 Iter: Gateway to the Middle Ages and Renaissance Tel: 416/978–7074 Email: [email protected] Fax: 416/978–1668 Web: www.itergateway.org Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Victoria University in the University of Toronto Tel: 416/585–4465 Email: [email protected] Fax: 416/585–4430 Web: www.crrs.ca © 2014 Iter Inc. & Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. Iter and the Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies gratefully acknowledge the generous support of James E. Rabil, in memory of Scottie W. Rabil, toward the publication of this book. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Portraits of the queen mother : polemics, panegyrics, letters / Catherine de Médicis and others ; translation and study by Leah L. Chang and Katherine Kong. (The other voice in early modern Europe. The Toronto series ; 35) Translated from the French. Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-0-7727-2172-3 (pbk).—ISBN 978-0-7727-2173-0 (pdf) 1. Catherine de Médicis, Queen, consort of Henry II, King of France, 1519–1589—Correspondence. 2. Queens—France—Biography. 3. Mothers—France—Biography. 4. France—Politics and govern- ment—16th century—Sources. I. Chang, Leah L., translator II. Kong, Katherine, translator III. Victoria University (Toronto, Ont.). Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, issuing body IV. Iter Inc., issuing body V.