Geneva Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metos, Merik the Vanishing Pope.Pdf

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY THE VANISHING POPE MERIK HUNTER METOS SPRING 2009 ADVISOR: DR. SPOHNHOLZ DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS Honors Thesis ************************* PASS WITH DISTINCTION JOSI~~ s eLf" \\)J I \%\1 )10 dW JOJ JOS!Ape S!SalH· S\;/ :383110J S~ONOH A.1IS~31\INn 3H.1 0.1 PRECIS Pope Benoit XIII (1328-1423), although an influential advocate for reforms within the Catholic Church in the middle ages, receives little attention from modem historians. Historians rarely offer more than a brief biography and often neglect to mention at all his key role in the Great Schism. Yet, the very absence ofPope Benoit XIU from most historical narratives of medieval history itself highlights the active role that historians play in determining what gets recorded. In some cases, the choices that people make in determining what does, and what does not, get included in historical accounts reveals as much about the motivations and intentions of the people recording that past as it does about their subjects. This essay studies one example of this problem, in this case Europeans during the Reformation era who self-consciously manipulated sources from medieval history to promote their own agendas. We can see this in the sixteenth-century translation ofa treatise written by the medieval theologian Nicholas de Clamanges (1363-1437. Clamanges was a university professor and served as Benoit XIII's secretary during the Great Schism in Avignon, France. The treatise, entitled La Traite de fa Ruine de f'Eglise, was written in Latin in 1398 and was first distributed after Clamanges' death in 1437. -

Service Music

Service Music 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 Indexes Copyright Permissions Copyright Page Under Construction 441 442 Chronological Index of Hymn Tunes Plainsong Hymnody 1543 The Law of God Is Good and Wise, p. 375 800 Come, Holy Ghost, Our Souls Inspire 1560 That Easter Day with Joy Was Bright, p. 271 plainsong, p. 276 1574 In God, My Faithful God, p. 355 1200?Jesus, Thou Joy of Loving Hearts 1577 Lord, Thee I Love with All My Heart, p. 362 Sarum plainsong, p. 211 1599 How Lovely Shines the Morning Star, p. 220 1250 O Come, O Come Emmanuel 1599 Wake, Awake, for Night Is Flying, p. 228 13th century plainsong, p. 227 1300?Of the Father's Love Begotten Calvin's Psalter 12th to 15th century tropes, p. 246 1542 O Food of Men Wayfaring, p. 213 1551 Comfort, Comfort Ye My People, p. 226 Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Melodies 1551 O Gladsome Light, p. 379 English 1551 Father, We Thank Thee Who Hast Planted, p. 206 1415 O Love, How Deep, How Broad, How High! English carol, p. 317 Bohemian Brethren 1415 O Wondrous Type! O Vision Fair! 1566 Sing Praise to God, Who Reigns Above, p. 324 English carol, p. 320 German Unofficial English Psalters and Hymnbooks, 1560-1637 1100 We Now Implore the Holy Ghost 1567 Lord, Teach Us How to Pray Aright -Thomas Tallis German Leise, p. -

The Theology of the French Reformed Churches Martin I

The Theology of the French Reformed Churches REFORMED HISTORICAL-THEOLOGICAL STUDIES General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Jay T. Collier BOOKS IN SERIES: The Christology of John Owen Richard W. Daniels The Covenant Theology of Caspar Olevianus Lyle D. Bierma John Diodati’s Doctrine of Holy Scripture Andrea Ferrari Caspar Olevian and the Substance of the Covenant R. Scott Clark Introduction to Reformed Scholasticism Willem J. van Asselt, et al. The Spiritual Brotherhood Paul R. Schaefer Jr. Teaching Predestination David H. Kranendonk The Marrow Controversy and Seceder Tradition William VanDoodewaard Unity and Continuity in Covenantal Thought Andrew A. Woolsey The Theology of the French Reformed Churches Martin I. Klauber The Theology of the French Reformed Churches: From Henri IV to the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes Edited by Martin I. Klauber Reformation Heritage Books Grand Rapids, Michigan The Theology of the French Reformed Churches © 2014 by Martin I. Klauber All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any man ner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Direct your requests to the publisher at the following address: Reformation Heritage Books 2965 Leonard St. NE Grand Rapids, MI 49525 6169770889 / Fax 6162853246 [email protected] www.heritagebooks.org Printed in the United States of America 14 15 16 17 18 19/10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 [CIP info] For additional Reformed literature, request a free book list from Reformation Heritage Books at the above regular or e-mail address. -

2012 Calvin Bibliography

2012 Calvin Bibliography Compiled by Paul W. Fields and Andrew M. McGinnis (Research Assistant) I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography B. Cultural Context—Intellectual History C. Cultural Context—Social History D. Friends E. Polemical Relationships II. Calvin’s Works A. Works and Selections B. Criticism and Interpretation III. Calvin’s Theology A. Overview B. Revelation 1. Scripture 2. Exegesis and Hermeneutics C. Doctrine of God 1. Overview 2. Creation 3. Knowledge of God 4. Providence 5. Trinity D. Doctrine of Christ E. Doctrine of the Holy Spirit F. Doctrine of Humanity 1. Overview 2. Covenant 3. Ethics 4. Free Will 5. Grace 6. Image of God 7. Natural Law 8. Sin G. Doctrine of Salvation 1. Assurance 2. Atonement 1 3. Faith 4. Justification 5. Predestination 6. Sanctification 7. Union with Christ H. Doctrine of the Christian Life 1. Overview 2. Piety 3. Prayer I. Ecclesiology 1. Overview 2. Discipline 3. Instruction 4. Judaism 5. Missions 6. Polity J. Worship 1. Overview 2. Images 3. Liturgy 4. Music 5. Preaching 6. Sacraments IV. Calvin and Social-Ethical Issues V. Calvin and Economic and Political Issues VI. Calvinism A. Theological Influence 1. Overview 2. Christian Life 3. Church Discipline 4. Ecclesiology 5. Holy Spirit 6. Predestination 7. Salvation 8. Worship B. Cultural Influence 1. Arts 2. Cultural Context—Intellectual History 2 3. Cultural Context—Social History 4. Education 5. Literature C. Social, Economic, and Political Influence D. International Influence 1. Australia 2. Eastern Europe 3. England 4. Europe 5. France 6. Geneva 7. Germany 8. Hungary 9. India 10. -

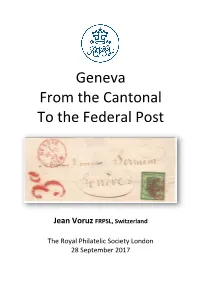

Geneva from the Cantonal to the Federal Post

Geneva From the Cantonal To the Federal Post Jean Voruz FRPSL, Switzerland The Royal Philatelic Society London 28 September 2017 Front cover illustration On 1 st October 1849, the cantonal posts are reorganized and the federal post is created. The Geneva cantonal stamps are still valid, but the rate for local letters is increased from 5 to 7 cents. As the "Large Eagle" with a face value of 5c is sold at the promotional price of 4c, additional 3c is required, materialized here by the old newspapers stamp. One of the two covers being known dated on the First Day of the establishment of the Federal Service. 2 Contents Frames 1 - 2 Cantonal Post Local Mail Frame 2 Cantonal Post Distant Mail Frame 3 Cantonal Post Sardinian & French Mail Frame 4 Transition Period Nearest Cent Frames 4 - 6 Transition Period Other Phases Frame 7 Federal Post Local Mail Frame 8 Federal Post Distant Mail Frames 9 - 10 Federal Post Sardinian & French Mail Background Although I started collecting stamps in 1967 like most of my classmates, I really entered the structured philately in 2005. That year I decided to display a few sheets of Genevan covers at the local philatelic society I joined one year before. Supported by my new friends - especially Henri Grand FRPSL who was one of the very best specialists of Geneva - I went further and got my first FIP Large Gold medal at London 2010 for the postal history collection "Geneva Postal Services". Since then the collection received the FIP Grand Prix International at Philakorea 2014 and the FEPA Grand Prix Finlandia 2017. -

1494:1 Russellville, Arkansas

10-11 z A HISTORICAL SURVEY OF PSALM SETTINGS FROM THE TIME OF THE REFORMATION THROUGH STRAVINSKY'S "SYMPHONIE DES PSAUMES" THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State Teachers College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Virginia Sue Williamson, B. M. 1494:1 Russellville, Arkansas August, 1947 14948i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.. .... .......... v Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ...... ....... ... 1 II. LATIN PSALM SETTINGS..... ....... 6 III. THE REFORMATION AND CHURCH MUSIC . 13 IV. EARLYPSALTERS . 25 The Genevan Psalter English Psalters C e Psalter Sternhold and-Hopkins Psalter D Psalter Este Psalter Allison's Psalter Ainsworth Psalter Ravencroft's Psalter John Keble Psalter Cleveland Psalter The Bay Psalm Book V. SCHUTZ TO STRAVINSKY. ........... 51 Heinrich Schutz (1585-1682) Henry Purcell (1658 or 1659-1695) George Frederic Handel (1685-1759) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Franz Peter Schubert (1797-1828) Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847) Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Cesar Franck (1822-1890) Charles Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921) Mikail M. Ippolotov-Ivanov (1859----- Charles Martin Loeffler (1861-----) iii Chapter Page Albert Roussel (1869- ---- ) Igor Stravinsky (1882 .---- ) VI. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION . 86 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 89 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. "L'Amour de moy" (Ps. 130), from the Psalter d'Anvers of 1541 . 32 2. Secular melody used by Bourgeois for Psalm 25 . 32 3. "Susato," used for Psalms 65 and 72 in Genevan Psalter .*.*.*. .*.9** .* . ,933 4. "Paris et Gevaet," used for Psalm 134 in the Genevan Psalter of 1551 . -

Introduction

Introduction The Other Voice [Monsieur de Voysenon] told [the soldiers] that in the past he had known me to be a good Catholic, but that he could not say whether or not I had remained that way. At that mo- ment arrived an honorable woman who asked them what they wanted to do with me; they told her, “By God, she is a Huguenot who ought to be drowned.” Charlotte Arbaleste Duplessis-Mornay, Memoirs The judge was talking about the people who had been ar- rested and the sorts of disguises they had used. All of this terrified me. But my fear was far greater when both the priest and the judge turned to me and said, “Here is a little rascal who could easily be a Huguenot.” I was very upset to see myself addressed that way. However, I responded with as much firmness as I could, “I can assure you, sir, that I am as much a Catholic as I am a boy.” Anne Marguerite Petit Du Noyer, Memoirs The cover of this book depicting Protestantism as a woman attacked on all sides reproduces the engraving that appears on the frontispiece of the first volume of Élie Benoist’s History of the Edict of Nantes.1 This illustration serves well Benoist’s purpose in writing his massive work, which was to protest both the injustice of revoking an “irrevocable” edict and the oppressive measures accompanying it. It also says much about the Huguenot experience in general, and the experience of Huguenot women in particular. When Benoist undertook the writing of his work, the association between Protestantism and women was not new. -

Concordia Journal

CONCORDIA JOURNAL Volume 28 July 2002 Number 3 CONTENTS ARTICLES The 1676 Engraving for Heinrich Schütz’s Becker Psalter: A Theological Perspective on Liturgical Song, Not a Picture of Courtly Performers James L. Brauer ......................................................................... 234 Luther on Call and Ordination: A Look at Luther and the Ministry Markus Wriedt ...................................................................... 254 Bridging the Gap: Sharing the Gospel with Muslims Scott Yakimow ....................................................................... 270 SHORT STUDIES Just Where Was Jonah Going?: The Location of Tarshish in the Old Testament Reed Lessing .......................................................................... 291 The Gospel of the Kingdom of God Paul R. Raabe ......................................................................... 294 HOMILETICAL HELPS ..................................................................... 297 BOOK REVIEWS ............................................................................... 326 BOOKS RECEIVED ........................................................................... 352 CONCORDIA JOURNAL/JULY 2002 233 Articles The 1676 Engraving for Heinrich Schütz’s Becker Psalter: A Theological Perspective on Liturgical Song, Not a Picture of Courtly Performers James L. Brauer The engraving at the front of Christoph Bernhard’s Geistreiches Gesang- Buch, 1676,1 (see PLATE 1) is often reproduced as an example of musical PLATE 1 in miniature 1Geistreiches | Gesang-Buch/ -

Geneva and CERN

Welcome to Geneva and CERN The local organizing committee would like to welcome you to Geneva for the Fifth International Workshop on Analogue and Mixed-Signal Integrated Circuits for Space Applications “AMICSA 2014”. The workshop is organized by the European Space Agency, ESA and the European Organization for Nuclear Research, CERN. The year 2014 holds a particular significance for CERN: on 29 September it will be exactly 60 years since the Organization was created. Founded by 12 members in 1954, the CERN laboratory sits astride the Franco-Swiss border near Geneva. It was one of Europe's first joint ventures and now has 21 member states. The name CERN is derived from the acronym for the French "Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire", or European Council for Nuclear Research, a provisional body founded in 1952 with the mandate of establishing a world-class fundamental physics research organization in Europe. At that time, pure physics research concentrated on understanding the inside of the atom, hence the word "nuclear". Today, our understanding of matter goes much deeper than the nucleus, and CERN's main area of research is particle physics – the study of the fundamental constituents of matter and the forces acting between them. Because of this, the laboratory operated by CERN is often referred to as the European Laboratory for Particle Physics. Physicists and engineers are probing the fundamental structure of the universe. They use the world's largest and most complex scientific instruments to study the basic constituents of matter – the fundamental particles. The particles are made to collide together at close to the speed of light. -

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France Bethany Hume PhD University of York History September 2019 2 Abstract This thesis responds to the historiographical focus on the trope of the Albigensians and Waldensians within sixteenth-century confessional polemic. It supports a shift away from the consideration of medieval heresy in early modern historical writing merely as literary topoi of the French Wars of Religion. Instead, it argues for a more detailed examination of the medieval heretical and inquisitorial sources used within seventeenth-century French intellectual culture and religious polemic. It does this by examining the context of the Doat Commission (1663-1670), which transcribed a collection of inquisition registers from Languedoc, 1235-44. Jean de Doat (c.1600-1683), President of the Chambre des Comptes of the parlement of Pau from 1646, was charged by royal commission to the south of France to copy documents of interest to the Crown. This thesis aims to explore the Doat Commission within the wider context of ideas on medieval heresy in seventeenth-century France. The periodization “medieval” is extremely broad and incorporates many forms of heresy throughout Europe. As such, the scope of this thesis surveys how thirteenth-century heretics, namely the Albigensians and Waldensians, were portrayed in historical narrative in the 1600s. The field of study that this thesis hopes to contribute to includes the growth of historical interest in medieval heresy and its repression, and the search for original sources by seventeenth-century savants. By exploring the ideas of medieval heresy espoused by different intellectual networks it becomes clear that early modern European thought on medieval heresy informed antiquarianism, historical writing, and ideas of justice and persecution, as well as shaping confessional identity. -

18Summer-Vol24-No3-TM.Pdf

Theology Matters Vol 24, No. 3 Summer 2018 Rediscovering the Office of Elder The Shepherd Model by Eric Laverentz At the center of our name, tradition, identity, and ethos guard the purity of the church in the lives of its as Presbyterians is a term that has lost almost all members. In dealing with offenses, the session holds connection with what it meant to most who have called both judiciary and executive authority. But the most themselves Presbyterians over the last five centuries. important function of elders is to watch over the flock, Even to many of our parents and grandparents being a of which they are under-shepherds, guarding, “presbyter” or “elder” meant something quite different counseling, comforting, instructing, encouraging, and than it means to most of us today. admonishing, as circumstances require. The penalties imposed on wrongdoers are censure, suspension from The not too distant past paints a picture of elders vested the communion of the Church, and excommunication.1 with spiritual authority who were deeply enmeshed in the lives of people. This is very different from the As foreign as this description of duties sounds to 21st service rendered in most elder-led churches today. We century ears, it was not the elders of First Presbyterian have seen a total shift in understanding of what it Church, Dayton, Ohio, in the 1880s who were guarding means to be an elder over the last generation or two. the purity of their members and exercising discipline The shift is so complete that few of us have any that were out of touch with the historical and Biblical institutional memory of the way it used to be. -

Psalm 100 Sweelinck, Ed

CM9412 Psalm 100 Sweelinck, ed. Hooper / SAATB a cappella Psalm 100 Vous tous qui la terr’ habitez Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck For RANDALL HOOPER unlawfulpromotional SAATB Voices a cappella Duration: 3:49 to RANGES: copy use or only print FREE MP3 rehearsal and accompaniments www.carlfischer.com 2 About the Composer Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621) was born and raised in Amsterdam. He worked as the organist at the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam from ca. 1580 until his death in 1621. Because the Calvinists saw the organ as a worldly instrument and forbade its use during religious services, he was actually a civil servant employed by the city of Amsterdam. It is assumed that his duties were to provide music twice daily in the church, an hour in the morning and in the evening. When there was a service, this hour came before and/or after the service. As well as being one of the most famous organists and teachers of this time, Sweelinck was the last and most important com- poser of the musically rich golden era of the Netherlanders. All of his vocal works Forwere printed in his lifetime. His polyphonic setting of Psalter has been called a monu- ment of Netherlandish music, unequalled in the sphere of sacred polyphony. From the outset he intended to set the entire Psalter, and he dedicated much of his creative life unlawfulto this music.promotional The texts are from the French metrical Psalter, not the Dutch version which was used in most Dutch churches. This is probably because the psalms were not intended for use in public Calvinist services but rather within a circle of well-to-do musical amateurs among whom French was the preferred language.