Guide to Pain Management in Low-Resource Settings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

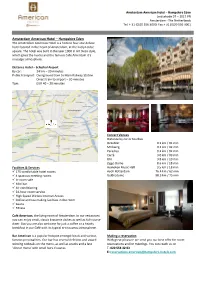

Amsterdam American Hotel – Hampshire Eden Leidsekade 97 – 1017 PN Amsterdam - the Netherlands Tel

Amsterdam American Hotel – Hampshire Eden Leidsekade 97 – 1017 PN Amsterdam - The Netherlands Tel. + 31 (0)20 556 3000, Fax.+ 31 (0)20 556 3001 Amsterdam American Hotel – Hampshire Eden The Amsterdam American Hotel is a historic four-star deluxe hotel located in the heart of Amsterdam, at the lively Leidse square. The hotel was built in the year 1900 in Art Deco style, which gives the rooms and the famous Café Americain it’s nostalgic atmosphere. Distance Hotel – Schiphol Airport By car: 24 km – 20 minutes Public transport: Overground tram to Main Railway Station. Direct train to airport – 20 minutes Taxi: EUR 40 – 20 minutes Concert Venues Distance by car or tourbus DeLaMar 0.1 km / 01 min Melkweg 0.2 km / 02 min Paradiso 0.2 km / 02 min Carré 3.0 km / 09 min RAI 3.8 km / 10 min Ziggo Dome 8.6 km / 18 min Facilities & Services Heineken Music Hall 9.5 km / 18 min 175 comfortable hotel rooms Ayoh Rotterdam 76.4 km / 62 min 4 spacious meeting rooms Geldredome 98.5 km / 75 min In-room safe Mini bar Air conditioning 24-hour room service High Speed Wirless Internet Access Coffee and tea making facilities in the room Sauna Fitness Café American , the living room of Amsterdam. In our restaurant you can enjoy small, classic brasserie dishes as well as full-course diner. But you are also welcome for just a coffee or a hearty breakfast in our Café with its typical art nouveau atmosphere. Bar American is a popular hotspot amongst locals and various Making a reservation famous personalities. -

Physiology H Digestive

2/28/18 Introduction • Provides processes to break down molecules into a state easily used by cells - A disassembly line: Starts at the mouth and ends Digestive System at the anus • Digestive functions are initiated by the parasympathetic division Chapter 29 - Digestion occurs during periods of low activity - Produces more energy than it uses Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 2 Anatomy The Digestive System • Oral cavity • Pharynx • Esophagus • Stomach • Small intestine and large intestine • Accessory organs: Pancreas, liver, and gallbladder From Herlihy B: The human body in health and illness, ed 4, St. Louis, 2011, Saunders. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 3 Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Physiology Gastrointestinal Tract • Ingestion: Taking materials into mouth by • Muscular tube throughout digestive system eating/drinking • Accessory organs and glands secrete • Digestion: Breaking down food into molecules substance to aid in digestion that can be used by the body • GI tract wall has four layers: - Includes mechanical and enzymatic action - Mucosa • Absorption: Simple molecules from the - Submucosa gastrointestinal (GI) tract move into the - Muscle layer: Responsible for peristalsis bloodstream or lymph vessels and then into - Serosa body cells • Defecation: Eliminating indigestible or unabsorbed material from the body Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 5 Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 6 1 2/28/18 Peristalsis Oral Cavity • First portion of GI tract • Contains: - Teeth - Tongue - Openings for salivary glands From Thibodeau GA, Patton KT: Anatomy & physiology, ed 6, St. -

Post Spinal Headache (PDPH), Spinal Headache, Spinal Needle

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Post Spinal Headache (PDPH), Spinal Headache, Spinal Needle KHALID RAFIQUE1, MUHAMMAD SAEED2, IFTIKHAR AHMAD CHAUDHRY3, SHAHID MAHMOOD4, MUHAMMAD TAMUR5, TANVEER SADIQ6, ABDUL QAYYUM7 ABSTRACT Aim: To compare the frequency of postdural puncture headache (PDPH) using 25 and 27 gauge Quincke needles in a population of young patients undergoing caesarian sections under general anesthesia. Methods: It was a prospective interventional study in which ninety patients were divided into two groups. Patient’s age, ASA classification, nature of surgery (elective or emergency) and position (sitting or lateral decubitus) during induction of spinal anesthesia were recorded. The patients were interviewed first through third post-operative days about the occurrence of headache and their satisfaction regarding spinal anesthesia. Conclusion: t was found that the proportion of patients with PDPH after 25 gauge Quincke needle was significantly more than those with 27 gauge Quincke. Keywords: Spinal headache, spinal headache, spinal needle INTRODUCTION Correspondence to Dr. Khalid Rafique Cell: 03335118167 E-mail: [email protected] Spinal anesthesia is the technique of choice for administered by August Bier (1861–1949) on 16 Caesarean Section as it avoids general anesthetics. August 1898, when he injected 3 ml of 0.5% cocaine If surgery allows spinal anesthesia, it is very useful in solution into a 34-year-old labourer. They 6 patients with severe respiratory diseases e.g. COPD recommended it for surgeries of legs , but later on as it avoids complications related to intubation and gave it up due to the toxicity of cocaine. Carl Koller, ventilation. It may also be useful in patients where an ophthalmologist from Vienna, first described the anatomical abnormalities may make endotracheal use of topical cocaine for analgesia of the eye in 7 intubation very difficult. -

Ik Ben Ilse Hoeflaak, Kom Uit Santpoort En Woon Al 10 Jaar in Haarlem En Ken Veel Leuke Plekjes Daar

Ik ben Ilse Hoeflaak, kom uit Santpoort en woon al 10 jaar in Haarlem en ken veel leuke plekjes daar. Zelf hou ik van reizen, cultuur, zon, zee, strand, lezen, sporten, muziek en dansen. Van zonnen op het strand, leren surfen, borrelen op het terras of een concert zien bij Woodstock of in het magische openluchttheater Caprera midden in het bos! Hieronder mijn hoogtepunten van Haarlem en omstreken: Activiteiten - Mooi weer: wijnproeverij met Chateau78 door de grachten van Haarlem, zonnen bij strandtent Woodstock, concert in openluchttheater Caprera of een biertje bij het kampvuur bij stadsstrand de Oerkap. - Slecht weer: Bikram yoga, naar cultfilm in de Toneelschuur en winkelen in Haarlem en Amsterdam. Winkel-Tip! Snuffel eens rond bij de Kleine Houtstraat en de Schachelstraat in Haarlem. Onder andere aparte boetiekjes, conceptstores, antiek-, woon- en kledingwinkels (surf en vintage) als Number Nine, Revert & ID. Voor 2ehands meubeltjes Stijlloods, Rataplan Haarlem en Vintagestore Hoofddorp. Koffie en Lunch Wolkers, Dodici (beste koffie), Blender, de Overkant, Staal (streekproducten en lezen), Spaarne 66 en op het terras bij restaurant Zuiddam aan het mooie Spaarne. Restaurants Ora (biologisch, Italiaans eten met binnentuin), Dodici (kleine gerechtjes en goede wijn), Klein Centraal (wat luxer in de buurt van camping, ook terras), Het Goede Uur (kaasfondue in authentieke setting), Truffels (luxer), Bruxelles (gezellig eetcafé), Erawan (Thais) en Indiacorner (Indiaas). Vooral in de Lange Veerstraat die doorgaat in de Kleine Houtstraat zijn heel veel leuke restaurantjes te vinden. Verder zit er in Overveen STACH met de lekkerste hamburgers en biologische maaltijden om mee te nemen. Borrelen - Buiten: Brasserie van Beinum, stadstrand de Oerkap, het Veerkwartier (aan het meer), restaurant Zuiddam. -

Astria Suparak Is an Independent Curator and Artist Based in Oakland, California. Her Cross

Astria Suparak is an independent curator and artist based in Oakland, California. Her cross- disciplinary projects often address urgent political issues and have been widely acclaimed for their high-level concepts made accessible through a popular culture lens. Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art institutions and festivals across ten countries, including The Liverpool Biennial, MoMA PS1, Museo Rufino Tamayo, Eyebeam, The Kitchen, Carnegie Mellon, Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen, and Expo Chicago, as well as for unconventional spaces such as roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, sports bars, and rock clubs. Her current research interests include sci-fi, diasporas, food histories, and linguistics. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE (selected) . Independent Curator, 1999 – 2006, 2014 – Present Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art, film, music, and academic institutions and festivals across 10 countries, as well as for unconventional spaces like roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, elementary schools, sports bars, and rock clubs. • ART SPACES, BIENNIALS, FAIRS (selected): The Kitchen, MoMA PS1, Eyebeam, Participant Inc., Smack Mellon, New York; The Liverpool Biennial 2004, FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), England; Museo Rufino Tamayo Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico City; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego; FotoFest Biennial 2004, Houston; Space 1026, Vox Populi, Philadelphia; National -

E Pleura and Lungs

Bailey & Love · Essential Clinical Anatomy · Bailey & Love · Essential Clinical Anatomy Essential Clinical Anatomy · Bailey & Love · Essential Clinical Anatomy · Bailey & Love Bailey & Love · Essential Clinical Anatomy · Bailey & Love · EssentialChapter Clinical4 Anatomy e pleura and lungs • The pleura ............................................................................63 • MCQs .....................................................................................75 • The lungs .............................................................................64 • USMLE MCQs ....................................................................77 • Lymphatic drainage of the thorax ..............................70 • EMQs ......................................................................................77 • Autonomic nervous system ...........................................71 • Applied questions .............................................................78 THE PLEURA reections pass laterally behind the costal margin to reach the 8th rib in the midclavicular line and the 10th rib in the The pleura is a broelastic serous membrane lined by squa- midaxillary line, and along the 12th rib and the paravertebral mous epithelium forming a sac on each side of the chest. Each line (lying over the tips of the transverse processes, about 3 pleural sac is a closed cavity invaginated by a lung. Parietal cm from the midline). pleura lines the chest wall, and visceral (pulmonary) pleura Visceral pleura has no pain bres, but the parietal pleura covers -

Opioid Withdrawal ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 Mark S

Magdalena Anitescu Honorio T. Benzon Mark S. Wallace Editors Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine 123 Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine Magdalena Anitescu Honorio T. Benzon • Mark S. Wallace Editors Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine Editors Magdalena Anitescu Honorio T. Benzon Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care Department of Anesthesiology University of Chicago Medicine Northwestern University Chicago, IL Feinberg School of Medicine USA Chicago, IL USA Mark S. Wallace Division of Pain Medicine Department of Anesthesiology University of California San Diego School of Medicine La Jolla, CL USA ISBN 978-3-319-60070-3 ISBN 978-3-319-60072-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60072-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017960332 © Springer International Publishing AG 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Covering the Receiver

PERCUTANEOUS RADIOFREQUENCY THERMAL LUMBAR SYMPATHECTOMY AND ITS CLINICAL USE PERCUTANEOUS RADIOFREQUENCY THERMAL LUMBAR SYMPATHECTOMY AND ITS CLINICAL USE Thermische Iurn bale sympathectomie door mid del van· percutane radiofrequency en zijn klinische toepassing PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof. Dr. A.H.G. Rinnooy Kan en volgens besluit van het College van Dekanen. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op vrijdag 23 september 1988 om 15.00 uur door JANINA PERNAK geboren te Polen Eburon Delft 1988 PROMOTIECOMMISSIE: Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Erdmann Overige !eden: Prof. Dr. P. Scherpereel (Lille) Prof. Dr. O.T. Terpstra Prof. Dr. B.D.· Bangma CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS I INTRODUCTION 1 II AIMS OF STUDY 2 PART ONE: LITERATURE REVIEW Chapter 1 DIFFERENT THERAPIES IN THE REFLEX SYMPATHETIC DYSTROPHY 5 I Introduction 5 II Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy and its treatment 7 1 Physical therapy 9 2 Pharmacological intervention 9 3 Transcutaneous electrostimulation 10 4 Dorsal spinal cord stimulation 11 5 Acupuncture 13 6 Laser 13 7 Cryoanalgesia 15 8 Percutaneous facet joints denervation 17 9 Epidural blocks 17 10 Sympathetic blocks 19 11 Intravenous sympathetic blocks 20 12 Sympathectorp.y 20 Chapter 2 SYMPATHECTOMY 21 I Historical Review 21 II Lumbar sympathectomy: 21 a. surgical - technique 21 b. chemical - technique 23 III Comparison between surgical and chemical sympathectomy 25 IV Summary and conclusions 25 PART TWO : OWN INVESTIGATION AND FINDINGS -

M T/&Djd-Huu4'jkiftmf, ) 'Imuaf Ify ^€E/^Anj

m t/&dJd-HUu4'Jkif tmf , ) 'iMuafify ^€e/^anJ The one Idea which History exhibits as evermore developing itself into greater distinctness is the Idea of Humanity the noble e eavour to 5 u ; throw down all the barriers erected between men by prejudice and one-sided views ; and by setting aside the distinctions or Kengion, Country, and Colour, to treat th,e whole Human race as one broth.erh.ood , having one great object—the free development or our sjpmtual nature."—Humboldt's Cosmos. ^ ©on tentss. NEWS OF THE WEEK— page What is being Done by the Who Gave the " Timid Coun- Henri Heine "" 1017 A mtional Party '. ™^^—== ^^" 103* SS^B^^iSf £S p«bl.c 3S ^S^t ' " " ££ |hl S?;.iir: whiston- -:::::::::::: $2 PuE^n^AVsr::: iffi affairs- fS&SIKKfi^" 1SS1 Disfranchisement of Truehold " Norton Street," Marylebone 1038 The Newspaper Stamp Re- PORTFOLIO— Land Voters 103-i Catholics in Municipalities ... 1038 turns 1042 Underneath .. , 1052 Reinforcements for the East ... 1034 Tho Danish Struggle 103a The Working Man and his _;.,_ -„_ ,. Odd Proceedings 1034 The Sydenham Pete.... 1039 Teachers 1012 THE ARTS- Iiord Palmerston at Itomsey 1035 The Czar's own. Account ©f his Increase of the Army 1043 Drury Lane . 1053 £he Loss of the Arctic : 1035 Mission ; 1039 China Made Useful 1044 Mr. Peto and the Kins of Den- Germany and Bussia 1039 «»-«, miiu/.ii _ mark ••. .-.. 103G Another Arctic Expedition ... 1039 OPtN council- Births, Marriages, and Deaths 105 1 Mr.Bernal Osborne iti Tipperary 1036 ¦ The Public Health 1039 Babel 1014 „„.«.-.«-.. Mr. Urquhar-t at Newcastle 1037 Labour Movement in October 1040 COMMERCIAL AFFAIRS- College 1037 The LITERATURE-l lTCO . -

Perispinal Delivery of CNS Drugs

CNS Drugs (2016) 30:469–480 DOI 10.1007/s40263-016-0339-2 LEADING ARTICLE Perispinal Delivery of CNS Drugs Edward Lewis Tobinick1 Published online: 27 April 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Perispinal injection is a novel emerging method neurological improvement in patients with otherwise of drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS). intractable neuroinflammatory disorders that may ensue Physiological barriers prevent macromolecules from effi- following perispinal etanercept administration. Perispinal ciently penetrating into the CNS after systemic adminis- delivery merits intense investigation as a new method of tration. Perispinal injection is designed to use the enhanced delivery of macromolecules to the CNS and cerebrospinal venous system (CSVS) to enhance delivery related structures. of drugs to the CNS. It delivers a substance into the ana- tomic area posterior to the ligamentum flavum, an ana- tomic region drained by the external vertebral venous Key Points plexus (EVVP), a division of the CSVS. Blood within the EVVP communicates with the deeper venous plexuses of Perispinal injection is a novel method of drug the CSVS. The anatomical basis for this method originates delivery to the CNS. in the detailed studies of the CSVS published in 1819 by the French anatomist Gilbert Breschet. By the turn of the Perispinal injection utilizes the cerebrospinal venous century, Breschet’s findings were nearly forgotten, until system (CSVS) to facilitate drug delivery to the CNS rediscovered by American anatomist Oscar Batson in 1940. by retrograde venous flow. Batson confirmed the unique, linear, bidirectional and ret- Macromolecules delivered posterior to the spine are rograde flow of blood between the spinal and cerebral absorbed into the CSVS. -

Chapter 11 PAIN MANAGEMENT AMONG SOLDIERS with AMPUTATIONS

Pain Management Among Soldiers With Amputations Chapter 11 PAIN MANAGEMENT AMONG SOLDIERS WITH AMPUTATIONS † ‡ § RANDALL J. MALCHOW, MD*; KEVIN K. KING, DO ; BRENDA L. CHAN ; SHARON R. WEEKS ; AND JACK W. TSAO, MD, DPHIL¥ INTRODUCTION HISTORY NEUROPHYSIOLOGY AND MECHANISMS OF PAIN Neurophysiology Mechanism of Phantom Sensation and Phantom Limb Pain Residual Limb Pain MULTIMODAL PAIN MANAGEMENT IN AMPUTEE CARE Rationale Treatment Modalities LOW BACK PAIN FUTURE RESEARCH SUMMARY * Colonel, Medical Corps, US Army; Chief, Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Management, Department of Anesthesia and Operative Services, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3851 Roger Brooke Drive, Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234; formerly, Chief of Anesthesia, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3851 Roger Brooke Drive, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, and Program Director, Anesthesiology, Brooke Army Medical Center-Wilford Hall Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas † Major, Medical Corps, US Army; Resident Anesthesiologist, Department of Anesthesiology, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3851 Roger Brooke Drive, Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234 ‡ Research Analyst, CompTIA, 1815 South Meyers Road, Suite 300, Villa Park, Illinois 60181; Formerly, Research Assistant, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, 6900 Georgia Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20307 § Research Assistant, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, 6900 Georgia Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20307 ¥ Commander, Medical Corps, US Navy; Associate Professor, Department of Neurology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Room A1036, Bethesda, Maryland 20814; Traumatic Brain Injury Consultant, US Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 2300 E Street, NW, Washington, DC 229 Care of the Combat Amputee INTRODUCTION Pain management is increasingly recognized as a reducing hospital stay; decreasing cost; and improving critical aspect of the care of the polytrauma patient. -

08. Serdar Erdine.Indd

AĞRI 2009;21(4):133-140 REVIEW - DERLEME Neurolytic blocks: When, How, Why Nörolitik bloklar: Ne zaman, Nasıl, Niçin Serdar ERDİNE1 Summary Interventional techniques are divided into two categories: neuroablative and neuromodulatory procedures. Neuroablation is the physical interruption of pain pathways either surgically, chemically or thermally. Neuromodulation is the dynamic and functional inhibition of pain pathways either by administration of opioids and other drugs intraspinally or intraventricularly or by stimulation. Neuroablative techniques for cancer pain treatment have been used for more than a century. With the de- velopment of imaging facilities such as fl uoroscopy, neuroablative techniques can be performed more precisely and effi ciently. Key words: Neuroablative techniques; neurolytic blocks; radiofrequency thermocoagulation. Özet Girişimsel teknikler nöroablatif ve nöromodülatör işlemler olarak iki gruba ayrılırlar. Nöroablasyon, cerrahi, kimyasal veya ısı uy- gulamalarıyla ağrı yolaklarında fi ziksel iletinin kesilmesidir. Nöromodülasyon, stimülasyon uygulamasıyla veya intraventriküler ya da intraspinal uygulanan opioidler ve diğer ajanlarla ağrı yolaklarının dinamik ve fonksiyonel inhibisyonudur. Nöroablatif teknik- ler kanser tedavisinde yüzyıldan fazla zamandır kullanılmaktadır. Fluroskopi gibi görüntüleme araçlarındaki gelişmelerle nöroabla- tif uygulamalar daha doğru ve etkili bir şekilde gerçekleştirilmektedir. Anahtar sözcükler: Nöroablatif teknikler; nörolitik bloklar; radyofrekans termokoagulasyon. 1Department of