08. Serdar Erdine.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opioid Withdrawal ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 Mark S

Magdalena Anitescu Honorio T. Benzon Mark S. Wallace Editors Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine 123 Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine Magdalena Anitescu Honorio T. Benzon • Mark S. Wallace Editors Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine Editors Magdalena Anitescu Honorio T. Benzon Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care Department of Anesthesiology University of Chicago Medicine Northwestern University Chicago, IL Feinberg School of Medicine USA Chicago, IL USA Mark S. Wallace Division of Pain Medicine Department of Anesthesiology University of California San Diego School of Medicine La Jolla, CL USA ISBN 978-3-319-60070-3 ISBN 978-3-319-60072-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60072-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017960332 © Springer International Publishing AG 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Covering the Receiver

PERCUTANEOUS RADIOFREQUENCY THERMAL LUMBAR SYMPATHECTOMY AND ITS CLINICAL USE PERCUTANEOUS RADIOFREQUENCY THERMAL LUMBAR SYMPATHECTOMY AND ITS CLINICAL USE Thermische Iurn bale sympathectomie door mid del van· percutane radiofrequency en zijn klinische toepassing PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof. Dr. A.H.G. Rinnooy Kan en volgens besluit van het College van Dekanen. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op vrijdag 23 september 1988 om 15.00 uur door JANINA PERNAK geboren te Polen Eburon Delft 1988 PROMOTIECOMMISSIE: Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Erdmann Overige !eden: Prof. Dr. P. Scherpereel (Lille) Prof. Dr. O.T. Terpstra Prof. Dr. B.D.· Bangma CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS I INTRODUCTION 1 II AIMS OF STUDY 2 PART ONE: LITERATURE REVIEW Chapter 1 DIFFERENT THERAPIES IN THE REFLEX SYMPATHETIC DYSTROPHY 5 I Introduction 5 II Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy and its treatment 7 1 Physical therapy 9 2 Pharmacological intervention 9 3 Transcutaneous electrostimulation 10 4 Dorsal spinal cord stimulation 11 5 Acupuncture 13 6 Laser 13 7 Cryoanalgesia 15 8 Percutaneous facet joints denervation 17 9 Epidural blocks 17 10 Sympathetic blocks 19 11 Intravenous sympathetic blocks 20 12 Sympathectorp.y 20 Chapter 2 SYMPATHECTOMY 21 I Historical Review 21 II Lumbar sympathectomy: 21 a. surgical - technique 21 b. chemical - technique 23 III Comparison between surgical and chemical sympathectomy 25 IV Summary and conclusions 25 PART TWO : OWN INVESTIGATION AND FINDINGS -

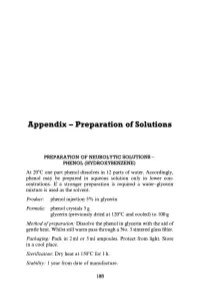

Appendix - Preparation of Solutions

Appendix - Preparation of Solutions PREPARATION OF NEUROLYTIC SOLUTIONS - PHENOL (HYDROXYBENZENE) At 20 0 e one part phenol dissolves in 12 parts of water. Accordingly, phenol may be prepared in aqueous solution only in lower con centrations. If a stronger preparation is required a water-glycerin mixture is used as the solvent. Product: phenol injection 5% in glycerin Formula: phenol crystals 5 g glycerin (previously dried at 120 0 e and cooled) to 100 g Method o/preparation: Dissolve the phenol in glycerin with the aid of gentle heat. Whilst still warm pass through a No.3 sintered glass filter. Packaging: Pack in 2 ml or 5 ml ampoules. Protect from light. Store in a cool place. Sterilization: Dry heat at 1500 e for 1 h. Stability: 1 year from date of manufacture. 185 186 Appendix Product: aqueous phenol 5% phenol injection 7% Formula: phenol crystals 5 g phenol crystals 7 g water for injections glycerin 50% v/v in water for injec to 100ml tions to 100 ml Method of preparation: Pass through sintered glass filter, pack in ampoules and sterilize by autoclaving at U5°e for 30 min. Packaging: 2 ml or 5 ml ampoules. Protect from light. Store in a cool place. Precautions: Avoid prolonged contact with rubber or plastics. Stability: 1 year from date of sterilization. INJECTION ABSOLUTE ALCOHOL Method ofpreparation: In order to avoid absorption of moisture, the infiltration procedure is best carried out under positive pressure, using solvent inert membrane filters. The preparation is then packed in 2 ml or 5 ml ampoules. Sterilization: Autoclave at 155°e for 30 min. -

Relative Potency and Duration of Analgesia Following Palmar Digital Intra-Neural Alcohol Injection for Heel Pain in Horses

Relative potency and duration of analgesia following palmar digital intra-neural alcohol injection for heel pain in horses THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christine Pariseau Schneider Graduate Program in Veterinary Clinical Sciences The Ohio State University 2013 Master's Examination Committee: Alicia Bertone, Advisor Michael Oglesbee Lisa Zekas Copyrighted by Christine Pariseau Schneider 2013 Abstract Objective: To determine the potency (percent analgesia), duration of action (up to four months), and clinical and histological effects of surgical exposure and intra-neural injection of 98% dehydrated medical-grade ethyl alcohol compared to no treatment (negative control), sham operation (surgical control), or formaldehyde injection (positive control) to decrease experimentally-induced palmar heel pain in horses. Animals: Six horses Procedures: The horses were fitted with a custom pressure-inducing shoe and had outcome measurements for each heel performed before and after nerve treatments. Outcomes included induced lameness grade and vertical peak force with pressure applied to each heel, thermal and touch sensation for each heel, and pastern circumference. Outcomes were followed serially for 112 days when nerves were harvested for histology. Results: Alcohol and formaldehyde reduced all measures of heel pain which progressed toward return, but persisted over the 112 days of the study (P<0.05). Pastern circumference was not different for alcohol than sham treatment, but was greater in formaldehyde than alcohol or baseline (P<0.05). Histological evaluation showed preservation of nerve fiber alignment with an intact epineurium, loss of axons (axon drop out), axon degeneration, fibrosis and inflammation in alcohol- and formaldehyde-injected ii nerves compared to control nerves. -

C Afferent Axons/Fibers C and a Fibers Cachexia CACNA1A Calbindin

C nated, polymodal C-fibers are activated by a variety C Afferent Axons/Fibers of high-intensity mechanical, chemical, hot and cold stimuli. In addition, low threshold fibers (Aβ) that nor- Synonyms mally only transfer innocuous sensations like touch, can CFibers contribute to neuropathic pain following nerve damage. Opioids in the Periphery and Analgesia Definition One kind of fiber in the peripheral nerve; unmyelinated thin fibers. These high-threshold sensory afferents con- duct very slowly (less than 2 m/s), and are thought to be Cachexia responsible for the sensation of deep, burning pain that follows ’first pain’ after injury. Although C fibers ma- Definition β ture earlier than low-threshold A fibers, anatomically General ill health and malnutrition that presents as mus- and neurochemically, other aspects of their function are cle wasting, dehydration and reduced behavioral activ- delayed, for example, the phenomenon of neurogenic ities in untreated diabetic animals. edema, and the development of functional central con- NeuropathicPainModel,DiabeticNeuropathyModel nections within the spinal cord. AFibers(A-Fibers) Alpha(α) 2-Adrenergic Agonists in Pain Treatment Infant Pain Mechanisms CACNA1A Insular Cortex, Neurophysiology and Functional Imaging of Nociceptive Processing Magnetoencephalography in Assessment of Pain in Definition Humans α CACNA1A is a gene encoding the 1A subunit of a Morphology, IntraspinalOrganizationofVisceralAf- voltage sensitive calcium channel abundantly expressed ferents in neuronal tissue. It is activated by high voltage and Nociceptor, Categorization gives rise to P/Q-type calcium currents. Mutations in Nociceptors in the Orofacial Region (Temporo- the human gene are related to diseases like spinocere- mandibular Joint and Masseter Muscle) bellar ataxia type 6, familial hemiplegic migraine and Nociceptor(s) episodic ataxia type 2. -

Neurolytic Block of Ganglion of Walther for the Management of Chronic Pelvic Pain

Case report Videosurgery Neurolytic block of ganglion of Walther for the management of chronic pelvic pain Małgorzata Malec-Milewska1, Bartosz Horosz1, Iwona Kolęda2, Agnieszka Sękowska2, Hanna Kucia2, Dariusz Kosson1,3, Grzegorz Jakiel4 1Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Medical Center for Postgraduate Education, Warsaw, Poland 2Pain Clinic, Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Medical Center for Postgraduate Education, Warsaw, Poland 31st Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Warsaw Medical University, Warsaw, Poland 41st Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical Center for Postgraduate Education, Warsaw, Poland Videosurgery Miniinv 2014; 9 (3): 458–462 DOI: 10.5114/wiitm.2014.43079 Abstract Here we report on the use of neurolytic block of ganglion impar (ganglion of Walther) for the management of in- tractable chronic pelvic pain, which is common enough to be recognized as a problem by gynecologists, likely to be difficult to diagnose and even more challenging to manage. Following failure in controlling the symptoms with phar- macological management, nine women underwent neurolysis of the ganglion impar in our Pain Clinic from 2009 to March 2013. The indication for the procedure was chronic pelvic pain (CPP) of either malignancy-related (4) or other origin (5). The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and duration of pain relief were employed to assess effectiveness of the procedure. Neurolysis was efficacious in patients with both malignancy-related CPP and CPP of non-malignant origin. Reported relief time varied from 4 weeks to 3 years, while in 4 cases complete and permanent cessation of pain was achieved. No complications were noted. Key words: ganglion impar, ganglion of Walther, neurolytic block, chronic cancer pain, chronic pelvic pain, Numeric Rating Scale. -

Clinical Policy: Nerve Blocks for Pain Management Reference Number: PA.CP.MP.170 Coding Implications Effective Date: 09/18 Revision Log Last Review Date: 09/18

Clinical Policy: Nerve Blocks for Pain Management Reference Number: PA.CP.MP.170 Coding Implications Effective Date: 09/18 Revision Log Last Review Date: 09/18 Description Nerve blocks are the temporary interruption of conduction of impulses in peripheral nerves or nerve trunks created by the injection of local anesthetic solutions. They can be used to identify the source of pain or to treat pain. Policy/Criteria It is the policy of Pennsylvania Health and Wellness® that invasive pain management procedures performed by a physician are medically necessary when the relevant criteria are met and the patient receives only one procedure per visit, with or without radiographic guidance. Table of Contents I. Occipital Nerve Block................................................................................................... 1 II. Sympathetic Nerve Block. ............................................................................................ 2 III. Celiac Plexus Nerve Block/Neurolysis ......................................................................... 3 IV. Intercostal Nerve Block/Neurolysis .............................................................................. 3 V. Genicular Nerve Blocks and Genicular Nerve Radiofrequency Neurotomy ................ 3 VI. Peripheral/Ganglion Nerve Blocks for the Treatment of Chronic Nonmalignant Pain 3 I. Occipital Nerve Block A. An initial injection of a local anesthetics for the diagnosis of suspected occipital neuralgia is medically necessary when all of the following are met: 1. Patient has unilateral or bilateral pain located in the distribution of the greater, lesser and/or third occipital nerves; 2. Pain has two of the following three characteristics: a. Recurring in paroxysmal attacks lasting from a few seconds to minutes; b. Severe intensity; c. Shooting, stabbing, or sharp in quality; 3. Pain is associated with both of the following: a. Dysesthesia and/or allodynia apparent during innocuous stimulation of the scalp and/or hair; b. -

| Oa Tai Ei to Ka Marratu Wa Kitu

|OA TAI EI US009855317B2TO KAMARRATU WA KITU (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 9 , 855 ,317 B2 Bright (45 ) Date of Patent: Jan . 2 , 2018 ( 54 ) SYSTEMS AND METHODS FOR ( 56 ) References Cited SYMPATHETIC CARDIOPULMONARY NEUROMODULATION U . S . PATENT DOCUMENTS 4 ,029 ,793 A 6 / 1977 Adams et al. (71 ) Applicant : Reflex Medical, Inc. , Los Altos Hills , 4 , 582 , 865 A 4 / 1986 Balazs et al. CA (US ) 6 , 545, 067 B1 4 / 2003 Büchner et al. 6 , 746, 464 B1 6 / 2004 Makower 6 , 932, 971 B2 8 / 2005 Bachmann et al. ( 72 ) Inventor: Corinne Bright , Los Altos Hills , CA 6 , 937 , 896 B1 8 / 2005 Kroll (US ) 7 , 928 ,141 B2 4 / 2011 Li 8 , 175 , 711 B2 5 / 2012 Demarais et al . ( 73 ) Assignee : Reflex Medical , Inc ., Los Altos Hills , 8 , 206 , 299 B2 6 / 2012 Foley et al . 8 , 211 , 017 B2 7 / 2012 Foley et al . CA (US ) 8 ,465 , 752 B2 6 / 2013 Seward 8 , 480, 651 B2 7 / 2013 Abuzaina et al . ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 8 , 708, 995 B2 4 / 2014 Seward et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 9 , 011 , 879 B2 4 / 2015 Seward U . S . C . 154 (b ) by 0 days. 9 , 199 ,065 B2 12 /2015 Seward 2002 /0037919 AL 3 / 2002 Hunter 2005 /0228460 A110 / 2005 Levin et al . ( 21 ) Appl. No. : 15 /140 ,254 2005 /0261672 AL 11 /2005 Deem et al . (22 ) Filed : Apr. 27 , 2016 2006 /0280797 Al 12 /2006 Shoichet et al. (Continued ) (65 ) Prior Publication Data US 2016 /0317621 A1 Nov . -

Neurolytic Celiac Plexus Blockade in Patients with Upper Intraabdominal Malignancies: an Evidence-Based Narrative Review

Graduate Medical Education Research Journal Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 5 December 2020 Neurolytic Celiac Plexus Blockade in Patients with Upper Intraabdominal Malignancies: An Evidence-Based Narrative Review Kevin Wong Desert Orthopedic Center Apollo A. Stack University of Nebraska Medical Center Madhuri Are University of Nebraska Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/gmerj Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Wong, K., Stack, A. A., , Are, M. Neurolytic Celiac Plexus Blockade in Patients with Upper Intraabdominal Malignancies: An Evidence-Based Narrative Review. Graduate Medical Education Research Journal. 2020 Dec 09; 2(2). https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/gmerj/vol2/iss2/5 This Literature Review (Systematic or Meta-Analysis) is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Medical Education Research Journal by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neurolytic Celiac Plexus Blockade in Patients with Upper Intraabdominal Malignancies: An Evidence-Based Narrative Review Abstract Background: Cancer-related abdominal pain is a common symptom associated with upper intra- abdominal carcinoma, especially in patients with advanced disease and it has posed a significant therapeutic challenge to medical practitioners. Typically, cancer pain can be managed by following the World Health Organization 3-step analgesic ladder. However, analgesic use of opioids, the mainstay treatment for moderate-to-severe cancer-related pain, may be ineffective in a subset of cancer patients. Escalation of dosage may be limited by opioid-induced side effects. The aim of this study was to review the literature addressing the effect of neurolytic celiac plexus block (NCPB) on the palliation of pain emanating from advanced upper intra-abdominal malignancies. -

Primary Experience with Ct Guided Mandibular Nerve Block in Patients with Trigeminal Neuralgia

Al-Azhar Med. J. Vol. 46(2), April, 2017, 383-390 DOI: 10.12816/0038261 PRIMARY EXPERIENCE WITH CT GUIDED MANDIBULAR NERVE BLOCK IN PATIENTS WITH TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA By Samy M Abdelraouf *, Ashraf M Enite and Ola I Saleh Departments of Neurosurgery* and Radiodiagnosis, Al-Azhar Faculty of Medicine (Girls) ABSTRACT Background: Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a well-known facial pain syndrome characterized by excruciating paroxysmal shock pain attacks located in somato-sensensory distribution of trigeminal nerve. Mandibular affection is a common presentation of TN. Objectives: Studying the effect of injection of mandibular nerve with neurolytic solutions in trigeminal neuralgia that was unresponsive to pharmacotherapy. Patients and Method: This prospective study included 21 patients treated for mandibular neuralgia by percutaneous injection of absolute alcohol under guidance of CT image. Their ages ranged from 35-60 years and male to female was 3:4. All patients suffered from moderate to severe TN, and did not respond to medical treatment. Entry and trajectory of needle was planned by CT and after local anesthesia. Alcohol was injected at the exit of mandibular nerve from foramen ovale. Results: 85.7% of patients improved (71.4% became pain free and severity of pain decreased in 19%), while 9.6% of patients has no response after injection. The pain free patients became 61.9% after two years of follow up. Conclusion: CT guided mandibular nerve block by neurolytic agent as absolute alcohol and showed its effectiveness as minimal invasive treatment option for intractable trigeminal neuralgia. CT guidance provided a clear view to secure the safety, accuracy and selectivity of nerve block. -

Stanford Chronic Pain Management Resident Rotation Syllabus Version 2009-10 Updated December 1, 2010 Contents

Stanford Chronic Pain Management Resident Rotation Syllabus Version 2009-10 Updated December 1, 2010 http://paincenter.stanford.edu Contents Pain Management Faculty .................................................................................................................................... 3 Volunteer Clinical Faculty .................................................................................................................................. 3 Goals & Objectives ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Patient Care ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Medical Knowledge ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Practice-Based Learning & Improvement ......................................................................................................... 4 Interpersonal & Communication Skills .............................................................................................................. 5 Professionalism ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Systems-Based Practice .................................................................................................................................. -

UM Authorization Guideline 02/18 UM PAI 01 Page 1 of 9

IEHP UM Subcommittee Approved Authorization Guideline Guideline Pain Management–Interventional Guideline # UM_PAI 01 Treatment/Diagnostic Procedures Original Effective Date 8/10/11 Section Pain Management Revision Date 2/14/18 COVERAGE POLICY This guideline describes indications and requirements for approvals of the following: • Interventional pain management treatment and diagnostic procedures • Epidural steroid injections: laminar or transforaminal • Facet joint injection/medical branch nerve block • Nerve block • Trigger point injection • Sacroiliac joint injection Interventional Pain Management Treatment and Diagnostic Procedures IEHP considers interventional pain management treatment / diagnostic procedures medically necessary for the treatment of pain when the following INITIAL criteria, A, B, C, D and E are met. Patients who have undergone surgery (e.g., laminectomy, fusion, hardware placement) may forego INITIAL criteria (i.e. physical therapy, MRI, and other conservative measures). A. A thorough history and detailed physical exam should be documented to emphasize the type of pain, severity, exacerbating factors including position as well as contributing psychological disorders. B. The Member has a pain level greater than 3 out of 10 intensity (moderate to severe pain) based on a Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS). C. The Member has tried and failed three (3) months of using several classes of medications (NSAIDS, acetaminophen, muscle relaxants, etc.). D. The Member has tried and failed four (4) weeks of physical therapy. Treatment