C Afferent Axons/Fibers C and a Fibers Cachexia CACNA1A Calbindin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Opioid Withdrawal ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 Mark S

Magdalena Anitescu Honorio T. Benzon Mark S. Wallace Editors Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine 123 Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine Magdalena Anitescu Honorio T. Benzon • Mark S. Wallace Editors Challenging Cases and Complication Management in Pain Medicine Editors Magdalena Anitescu Honorio T. Benzon Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care Department of Anesthesiology University of Chicago Medicine Northwestern University Chicago, IL Feinberg School of Medicine USA Chicago, IL USA Mark S. Wallace Division of Pain Medicine Department of Anesthesiology University of California San Diego School of Medicine La Jolla, CL USA ISBN 978-3-319-60070-3 ISBN 978-3-319-60072-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60072-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017960332 © Springer International Publishing AG 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Covering the Receiver

PERCUTANEOUS RADIOFREQUENCY THERMAL LUMBAR SYMPATHECTOMY AND ITS CLINICAL USE PERCUTANEOUS RADIOFREQUENCY THERMAL LUMBAR SYMPATHECTOMY AND ITS CLINICAL USE Thermische Iurn bale sympathectomie door mid del van· percutane radiofrequency en zijn klinische toepassing PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof. Dr. A.H.G. Rinnooy Kan en volgens besluit van het College van Dekanen. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op vrijdag 23 september 1988 om 15.00 uur door JANINA PERNAK geboren te Polen Eburon Delft 1988 PROMOTIECOMMISSIE: Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Erdmann Overige !eden: Prof. Dr. P. Scherpereel (Lille) Prof. Dr. O.T. Terpstra Prof. Dr. B.D.· Bangma CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS I INTRODUCTION 1 II AIMS OF STUDY 2 PART ONE: LITERATURE REVIEW Chapter 1 DIFFERENT THERAPIES IN THE REFLEX SYMPATHETIC DYSTROPHY 5 I Introduction 5 II Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy and its treatment 7 1 Physical therapy 9 2 Pharmacological intervention 9 3 Transcutaneous electrostimulation 10 4 Dorsal spinal cord stimulation 11 5 Acupuncture 13 6 Laser 13 7 Cryoanalgesia 15 8 Percutaneous facet joints denervation 17 9 Epidural blocks 17 10 Sympathetic blocks 19 11 Intravenous sympathetic blocks 20 12 Sympathectorp.y 20 Chapter 2 SYMPATHECTOMY 21 I Historical Review 21 II Lumbar sympathectomy: 21 a. surgical - technique 21 b. chemical - technique 23 III Comparison between surgical and chemical sympathectomy 25 IV Summary and conclusions 25 PART TWO : OWN INVESTIGATION AND FINDINGS -

Person, Place, and Thing a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty

Person, Place, and Thing A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Sarah E. Einstein April 2016 © 2016 Sarah E. Einstein. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Person, Place, and Thing by SARAH E. EINSTEIN has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Dinty W. Moore Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT EINSTEIN, SARAH E., Ph.D., April 2016, English Person, Place, and Thing Director of Dissertation: Dinty W. Moore The dissertation is divided into two sections: an essay titled “The Self-ish Genre: Questions of Authorial Selfhood and Ethics in Creative Nonfiction” and an essay collection titled, Person, Place, and Thing. “The Self-ish Genre: Questions of Authorial Selfhood and Ethics in Creative Nonfiction” engages with late modern and postmodern theories of selfhood in the service of moving towards an understanding of the ethical nature of the authorial character in the personal essay. I will position the authorial character within the framework of Paul Ricouer’s construction of the narrative self, identifying it as an artifact of the work of giving an account of oneself. I will consider how this artifact can be imagined to function inside a Levinasian ethics, and ask whether or not the authorial character can adequately serve as an “Other” with whom both the reader interacts in their own formations of self. Finally, I will turn to Judith Butler to suggest a way the ethical act of giving an account of oneself can be rescued from the postmodern disposition of the self. -

Serena Williams Displayed Her Fitness with a Straight-Set Victory to Open Her Bank of the West Classic Title Hopes

Palo Vol. XXXV, Number 43 ■ August 1, 2014 Six injured Alto in University Avenue crash Page 5 www.PaloAltoOnline.comwww.PaloAlt oOnline.com It’s a healthy Serenareturn for Williams World’s top player hopes to use Bank of the West Classic to revitalize her career once again PAGE 48 Pulse 16 Transitions 17 Spectrum 18 Eating Out 23 Shop Talk 24 Movies 25 Puzzles 45 QArts Bridging the worlds of art and science Page 21 QSeniors Moldaw residents share their art Page 26 QHome Rebirth of the Victory Garden at MOAH Page 31 Living Well With and Beyond Cancer Celebration On behalf of the Stanford Cancer Center we would like to invite you, your family, including children and friends, to our first annual “Living Well With and Beyond Cancer Celebration.” If you have had cancer, have known someone with cancer or want to learn more about the Stanford Cancer Center please join us for a free, fun day of celebration. Saturday, August 16, 2014 • 11:00 am – 3:00 pm Check-in at 10:00 am with Opening Remarks at 11:30 am Stanford University Medical Center Alumni Lawn at Li Ka Shing Center 291 Campus Drive • Stanford, CA 94305 Register Today! livingwell.stanford.edu • 844.768.1863 Free Parking! Connect. Learn. Share. Grow. Learn how community organizations and Stanford services can help you live a healthy life, and research health topics with Stanford health librarians. Ask the Experts about common survivorship issues: nutrition, changes in energy, living with uncertainty and cancer in the family. Enjoy live music, FREE 15 minute reiki and chair massage, yoga, a kid’s corner with face painting, lunch, and much more. -

08. Serdar Erdine.Indd

AĞRI 2009;21(4):133-140 REVIEW - DERLEME Neurolytic blocks: When, How, Why Nörolitik bloklar: Ne zaman, Nasıl, Niçin Serdar ERDİNE1 Summary Interventional techniques are divided into two categories: neuroablative and neuromodulatory procedures. Neuroablation is the physical interruption of pain pathways either surgically, chemically or thermally. Neuromodulation is the dynamic and functional inhibition of pain pathways either by administration of opioids and other drugs intraspinally or intraventricularly or by stimulation. Neuroablative techniques for cancer pain treatment have been used for more than a century. With the de- velopment of imaging facilities such as fl uoroscopy, neuroablative techniques can be performed more precisely and effi ciently. Key words: Neuroablative techniques; neurolytic blocks; radiofrequency thermocoagulation. Özet Girişimsel teknikler nöroablatif ve nöromodülatör işlemler olarak iki gruba ayrılırlar. Nöroablasyon, cerrahi, kimyasal veya ısı uy- gulamalarıyla ağrı yolaklarında fi ziksel iletinin kesilmesidir. Nöromodülasyon, stimülasyon uygulamasıyla veya intraventriküler ya da intraspinal uygulanan opioidler ve diğer ajanlarla ağrı yolaklarının dinamik ve fonksiyonel inhibisyonudur. Nöroablatif teknik- ler kanser tedavisinde yüzyıldan fazla zamandır kullanılmaktadır. Fluroskopi gibi görüntüleme araçlarındaki gelişmelerle nöroabla- tif uygulamalar daha doğru ve etkili bir şekilde gerçekleştirilmektedir. Anahtar sözcükler: Nöroablatif teknikler; nörolitik bloklar; radyofrekans termokoagulasyon. 1Department of -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Autolux – Transit Transit 1

DEC. 2010 • VOL. 21 ISSUE # 264 • ALWAYS FREE • SLUGMAG.COM SaltLakeUnderGround 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround SaltLakeUnderGround 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 21• Issue # 264 •December 2010 • slugmag.com Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray [email protected] Editor: Angela H. Brown Jemie Sprankle Managing Editor: [email protected] Jeanette D. Moses Shauna Brennan Editorial Assistant: Ricky Vigil [email protected] Action Sports Editor: Marketing: Ischa Buchanan, Jea- Adam Dorobiala nette D. Moses, Jessica Davis, Billy Copy Editing Team: Jeanette D. Ditzig, Hailee Jacobson, Stephanie Moses, Rebecca Vernon, Ricky Buschardt, Giselle Vickery, Veg Vollum, Vigil, Esther Meroño, Liz Phillips, Katie Josh Dussere, Chrissy Hawkins, Emily Panzer, Rio Connelly, Joe Maddock, Burkhart, Rachel Roller, Jeremy Riley. Alexander Ortega, Mary Enge, Kolbie SLUG GAMES Coordinators: Mike Stonehocker, Cody Kirkland, Hannah Brown, Jeanette D. Moses, Mike Reff, Christian. Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Adam Doro- Daily Calendar Coordinator: biala, Jeremy Riley, Katie Panzer, Jake Jessica Davis Vivori, Brett Allen, Chris Proctor, Dave [email protected] Brewer, Billy Ditzig. Social Networking Coordinator: Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Katie Rubio Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Cover Photo: “Drawn” by Jake Garn Tony Bassett, Joe Jewkes, Jesse See page 18 Hawlish, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Heath, Design Interns: Adam Dorobiala, Adam Okeefe, Manuel Aguilar, Chris Eric Sapp Proctor, David Frohlich. Ad Designers: Todd Powelson, Office Interns: Jessica Davis, Jeremy Kent Farrington, -

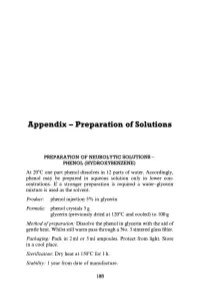

Appendix - Preparation of Solutions

Appendix - Preparation of Solutions PREPARATION OF NEUROLYTIC SOLUTIONS - PHENOL (HYDROXYBENZENE) At 20 0 e one part phenol dissolves in 12 parts of water. Accordingly, phenol may be prepared in aqueous solution only in lower con centrations. If a stronger preparation is required a water-glycerin mixture is used as the solvent. Product: phenol injection 5% in glycerin Formula: phenol crystals 5 g glycerin (previously dried at 120 0 e and cooled) to 100 g Method o/preparation: Dissolve the phenol in glycerin with the aid of gentle heat. Whilst still warm pass through a No.3 sintered glass filter. Packaging: Pack in 2 ml or 5 ml ampoules. Protect from light. Store in a cool place. Sterilization: Dry heat at 1500 e for 1 h. Stability: 1 year from date of manufacture. 185 186 Appendix Product: aqueous phenol 5% phenol injection 7% Formula: phenol crystals 5 g phenol crystals 7 g water for injections glycerin 50% v/v in water for injec to 100ml tions to 100 ml Method of preparation: Pass through sintered glass filter, pack in ampoules and sterilize by autoclaving at U5°e for 30 min. Packaging: 2 ml or 5 ml ampoules. Protect from light. Store in a cool place. Precautions: Avoid prolonged contact with rubber or plastics. Stability: 1 year from date of sterilization. INJECTION ABSOLUTE ALCOHOL Method ofpreparation: In order to avoid absorption of moisture, the infiltration procedure is best carried out under positive pressure, using solvent inert membrane filters. The preparation is then packed in 2 ml or 5 ml ampoules. Sterilization: Autoclave at 155°e for 30 min. -

Relative Potency and Duration of Analgesia Following Palmar Digital Intra-Neural Alcohol Injection for Heel Pain in Horses

Relative potency and duration of analgesia following palmar digital intra-neural alcohol injection for heel pain in horses THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christine Pariseau Schneider Graduate Program in Veterinary Clinical Sciences The Ohio State University 2013 Master's Examination Committee: Alicia Bertone, Advisor Michael Oglesbee Lisa Zekas Copyrighted by Christine Pariseau Schneider 2013 Abstract Objective: To determine the potency (percent analgesia), duration of action (up to four months), and clinical and histological effects of surgical exposure and intra-neural injection of 98% dehydrated medical-grade ethyl alcohol compared to no treatment (negative control), sham operation (surgical control), or formaldehyde injection (positive control) to decrease experimentally-induced palmar heel pain in horses. Animals: Six horses Procedures: The horses were fitted with a custom pressure-inducing shoe and had outcome measurements for each heel performed before and after nerve treatments. Outcomes included induced lameness grade and vertical peak force with pressure applied to each heel, thermal and touch sensation for each heel, and pastern circumference. Outcomes were followed serially for 112 days when nerves were harvested for histology. Results: Alcohol and formaldehyde reduced all measures of heel pain which progressed toward return, but persisted over the 112 days of the study (P<0.05). Pastern circumference was not different for alcohol than sham treatment, but was greater in formaldehyde than alcohol or baseline (P<0.05). Histological evaluation showed preservation of nerve fiber alignment with an intact epineurium, loss of axons (axon drop out), axon degeneration, fibrosis and inflammation in alcohol- and formaldehyde-injected ii nerves compared to control nerves. -

Read University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill University of Southern Maine Richard Grusin Jenny Rice University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee University of Kentucky M

2017 | VOL. 1, Nº. 1 CAPACIOUS JOURNAL FOR EMERGING AFFECT INQUIRY 2017 | VOL. 1, Nº. 1 CAPACIOUS JOURNAL FOR EMERGING AFFECT INQUIRY Vol. 1 No. 1 Capacious: Journal for Emerging Afect Inquiry is an open access journal and all content is licensed Capacious under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). ISBN-13: 978-1547053117 ISBN-10: 1547053119 capaciousjournal.com You are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially. You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. 2017 | Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry 1 (1) Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry is an open access, peer-reviewed, international journal that is, first and foremost, dedicated to the publication of writings and similar creative works on affect by degree-seeking students (Masters, PhD, brilliant undergraduates) across any and all academic disciplines. Secondarily, the Editorial team journal also welcomes contributions from early-career researchers, recent post-graduates, those approaching their study of affect independent of academia (by choice or not), and, on occasion, an established scholar with an ‘emerging’ idea that opens up new avenues for affect inquiry. The principal aim of Capacious is to ‘make room’ for a wide diversity of approaches and emerging voices CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF to engage with ongoing conversations in and around affect studies. -

Neurolytic Block of Ganglion of Walther for the Management of Chronic Pelvic Pain

Case report Videosurgery Neurolytic block of ganglion of Walther for the management of chronic pelvic pain Małgorzata Malec-Milewska1, Bartosz Horosz1, Iwona Kolęda2, Agnieszka Sękowska2, Hanna Kucia2, Dariusz Kosson1,3, Grzegorz Jakiel4 1Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Medical Center for Postgraduate Education, Warsaw, Poland 2Pain Clinic, Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Medical Center for Postgraduate Education, Warsaw, Poland 31st Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Warsaw Medical University, Warsaw, Poland 41st Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical Center for Postgraduate Education, Warsaw, Poland Videosurgery Miniinv 2014; 9 (3): 458–462 DOI: 10.5114/wiitm.2014.43079 Abstract Here we report on the use of neurolytic block of ganglion impar (ganglion of Walther) for the management of in- tractable chronic pelvic pain, which is common enough to be recognized as a problem by gynecologists, likely to be difficult to diagnose and even more challenging to manage. Following failure in controlling the symptoms with phar- macological management, nine women underwent neurolysis of the ganglion impar in our Pain Clinic from 2009 to March 2013. The indication for the procedure was chronic pelvic pain (CPP) of either malignancy-related (4) or other origin (5). The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and duration of pain relief were employed to assess effectiveness of the procedure. Neurolysis was efficacious in patients with both malignancy-related CPP and CPP of non-malignant origin. Reported relief time varied from 4 weeks to 3 years, while in 4 cases complete and permanent cessation of pain was achieved. No complications were noted. Key words: ganglion impar, ganglion of Walther, neurolytic block, chronic cancer pain, chronic pelvic pain, Numeric Rating Scale.