The Linguistics of Arrival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball. -

Earth, Fire and Water: Applying Novel Techniques to Eradicate the Invasive

Island invasives: eradication and management Cooper J.; R.J. Cuthbert, N.J.M. Gremmen, P.G. Ryan, and J.D. Shaw. Earth, fire and water: applying novel techniques to eradicate the invasive plant, procumbent pearlwort Sagina procumbens, on Gough Island, a World Heritage Site in the South Atlantic Earth, fire and water: applying novel techniques to eradicate the invasive plant, procumbent pearlwort Sagina procumbens, on Gough Island, a World Heritage Site in the South Atlantic J. Cooper1,2,3, R. J. Cuthbert4, N. J. M. Gremmen5, P. G. Ryan6 and J. D. Shaw2 1Animal Demography Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa. <[email protected]>. 2DST/NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602, South Africa. 3CORE Initiatives, 9 Weltevreden Avenue, Rondebosch 7700, South Africa. 4Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2DL, United Kingdom. 5Data-Analyse Ecologie, Hesselsstraat 11, 7981 CD Diever, The Netherlands. 6Percy FitzPatrick Institute DST/NRF Centre of Excellence, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa. Abstract The Eurasian plant procumbent pearlwort (Sagina procumbens) was first reported in 1998 on Gough Island, a cool-temperate island and World Heritage Site in the central South Atlantic. The first population was discovered adjacent to a meteorological station, which is its assumed point of arrival. Despite numerous eradication attempts, the species has spread along a few hundred metres of coastal cliff, but has not as yet been found in the island’s sub-Antarctic-like mountainous interior. -

Proposal to Establish a School of Management At

UCSC School of Management: Global Management for a Knowledge-Based Economy PROPOSAL TO ESTABLISH A SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ DRAFT: PRE-PROPOSAL FOR COMMITTEE ON PLANNING AND BUDGET, ACADEMIC SENATE, UCSC January 15, 2008 Nirvikar Singh Special Advisor to the Chancellor Professor of Economics Campus Mailing Address: Economics Department E-mail address: [email protected] Telephone number: 831-459-4093 Fax number: 831-459-5077 UCSC School of Management: Global Management for a Knowledge-Based Economy Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................................................................1 MISSION: BUILDING A REGIONAL HUB FOR GLOBAL MANAGEMENT .................................................4 THE EDUCATIONAL CONTEXT: EMERGING DEMANDS ON MANAGEMENT EDUCATION ................4 THE ECONOMIC CONTEXT: THE UC SYSTEM, INNOVATION AND SUPPORTING THE NEXT WAVE OF CALIFORNIA’S GROWTH...................................................................................................................................6 CORE THEMES: MANAGING CREATIVITYAND MANAGING GLOBALLY...............................................7 Academic Rationale.............................................................................................................................................8 Sectors and Issues................................................................................................................................................9 -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

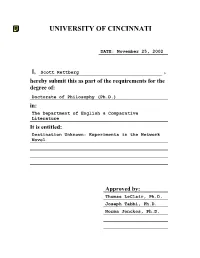

Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: November 25, 2002 I, Scott Rettberg , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in: The Department of English & Comparative Literature It is entitled: Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel Approved by: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. Joseph Tabbi, Ph.D. Norma Jenckes, Ph.D. Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2003 by Scott Rettberg B.A. Coe College, 1992 M.A. Illinois State University, 1995 Committee Chair: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. Abstract The dissertation contains two components: a critical component that examines recent experiments in writing literature specifically for the electronic media, and a creative component that includes selections from The Unknown, the hypertext novel I coauthored with William Gillespie and Dirk Stratton. In the critical component of the dissertation, I argue that the network must be understood as a writing and reading environment distinct from both print and from discrete computer applications. In the introduction, I situate recent network literature within the context of electronic literature produced prior to the launch of the World Wide Web, establish the current range of experiments in electronic literature, and explore some of the advantages and disadvantages of writing and publishing literature for the network. In the second chapter, I examine the development of the book as a technology, analyze “electronic book” distribution models, and establish the difference between the “electronic book” and “electronic literature.” In the third chapter, I interrogate the ideas of linking, nonlinearity, and referentiality. -

Digital Lab Reading List

A Sci Fi Guide to the 3D Shop Digital Lab Why is our digital equipment named? Each piece of technology develops its own personality and as we work on them we find ways to work with and communicate with them like you would another human. Who did we name them after? We chose science fiction writers because first of all these machines look like robots and who better to name them after then people who write about robots. Science fiction writers have also been inspiring cutting edge technology development for years. From Star Trek replicators inspiring 3D printers to flying cars inspiring self driving and energy efficient vehicles. Science fiction writers have been a major source of inspiration for makers of all kinds. We wanted to highlight some amazing writers and people who have contributed to that inspiration. This is only a very small number of great science fiction writers. If you know of any others that should be included, please share them with us. Interested in these writers' work? Check out our reading list below. If you discover new things by these writers, please share them with us! 3D Shop Digital Lab Reading List Here are some books to check out! ✩ = Can be found at the MCAD Library Nnedi Okorafor Binti Margaret Atwood (Marge) Zahrah the Windseeker Two Headed Poems (Jess’ Pick) N.K. Jemisin Oryx and Crake ✩ The Broken Earth Series (Jess’ Pick) Ray Bradbury The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms✩ The Illustrated Man Lesley Nneka Arimah Fahrenheit 451 ✩ What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky ✩ Octavia Butler Skinned ✩ Xenogenesis Series (Meagan’s Pick) Samuel R. -

Grade 9 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Night by Elie Wiesel

Grade 9 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Night by Elie Wiesel This grade 9 mini-assessment is based on an excerpt from Night by Elie Wiesel. This text is considered to be worthy of students’ time to read and also meets the expectations for text complexity at grade 9. Assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will employ quality, complex texts such as this one. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the text. Questions also may address several standards within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini- assessment there are nine selected-response questions and one paper/pencil equivalent of a technology-enhanced item that address the Reading Standards listed below, and one optional constructed-response question that addresses the Reading, Writing, and Language Standards listed below. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to the source. While we know that it is helpful to have students complete the mini-assessment in one class period, we encourage educators to allow additional time as necessary. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. If ELL students are receiving instruction in grade-level ELA content, they should be given access to unaltered practice assessment items to gauge their progress. -

GRAPHIC NOVELS AROUND the WORLD the Accidental Graphic

ISSN 0006 7377 manager (see inside front cover for contact details) For rates and information, contact our advertising Bookbird BE HERE! YOUR AD COULD ... Publishers, booksellers, Board on Books for Young People Young for Books on Board International the IBBY, of Journal The is distributed in 70 countries VOL. 49, NO.4 OCTOBER 2011 GRAPHIC NOVELS AROUND THE WORLD The accidental graphic novelist The artist as narrator: Shaun Tan’s wondrous worlds Not all that’s modern is post: •Shaun Tan’s grand narrative Striving to survive: Comic• strips in Iran The graphic novel in India: East transforms• west Educational graphic novels: Korean• children’s favorite now Raymond Briggs: Controversially• blurring boundaries Dave McKean’s art: Transcending• limitations of the graphic novel genre Picture books• as graphic novels and vice versa: The Australian experience Robot• Dreams and the language of sound effects • The Journal of IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People Copyright © 2011 by Bookbird, Inc. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Subscriptions consist of four issues and Editors: Catherine Kurkjian and Sylvia Vardell may begin with any issue. Rates include air Address for correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] freight for all subscriptions outside the USA and GST for Canadian subscribers. Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by Central Connecticut State University, New Britain, CT Check or money order must be in US dollars Editorial Review Board: Anastasia Arkhipova (Russia), Sandra Beckett (Canada), Ernest Bond (USA), Penni Cotton (UK), Hannelore Daubert (Germany), Reina Duarte (Spain), Toin Duijx (Netherlands), Nadia El Kholy (Egypt), and drawn on a US bank. -

The Novella As Technology: a Media Story

The Novella as Technology: A Media Story Kate Marshall* ABSTRACT This essay will situate the rise of the novella to prominence in contemporary liter- ary culture as a media-theoretical problem. The novella has emerged as a premier global form of contemporary literature. The subject of popular writing workshops and major reprint series by both trade and experimental publishing houses, it ca- ters to a desire for novelness in a moment of compressed time for writers and read- ers alike. But what is it about the form that drives our love of it? How does the relationship between time and technology structure its compelling status as well as the narratives of its history chosen to contextualize it? My examples, from the crucial subgenre of the SF novella as well as its experimental counterparts, will suggest that the mechanics of narrative length and ambition have been mobilized by contemporary writers and readers alike through the novella to reflexively recast relationships between fiction and technology. KEYWORDS the novella, temporality, science fiction, media, contemporary literature, publishing Ex-position, Issue No. 43, June 2020 | National Taiwan University DOI: 10.6153/EXP.202006_(43).0005 Kate MARSHALL, Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Notre Dame, USA 91 There is a moment early in Dinner, a recent novella by Argentinian writer César Aira, that stages an encounter between technology and the contemporary experi- ence of time so explicitly that something like literary form itself seems to emerge from it. The novella, first published in 2006 and then released in 2015 by New Directions in a translation by Katherine Silver, is by my count Aira’s forty-sixth, Ex-position and features a lonely narrator in Pringles who visits an old friend with his mother June 2020 for the first of the text’s eponymous meals. -

Biography and Memoir

Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Library, Arts & Culture To reserve a kit, please contact: [email protected] or call 818.548.2041 New Titles in the Collection — Fall 2018 Access the complete list at: http://www.glendaleca.gov/government/departments/library-arts-culture/services/book-group-kits The Alice Network by Kate Quinn Two women—a female spy recruited to the real-life Alice Network in France during World War I and an unconventional American socialite searching for her cousin in 1947—are brought together in a mesmerizing story of courage and redemption. Fiction. 560 pages. Barking to the Choir: The Power of Radical Kinship by Gregory Boyle In a nation deeply divided and plagued by poverty and violence, Barking to the Choir offers a snapshot into the challenges and joys of life on the margins. Sergio, arrested at nine, in a gang by twelve, and serving time shortly thereafter, now works with the substance-abuse team at Homeboy to help others find sobriety. Jamal, abandoned by his family when he tried to attend school at age seven, gradually finds forgiveness for his schizophrenic mother. New father Cuco, who never knew his own dad, thinks of a daily adventure on which to take his four-year-old son. These former gang members uplift the soul and reveal how bright life can be when filled with unconditional love and kindness. Biography and Memoir. 210 pages. Between Them: Remembering My Parents by Richard Ford A stirring narrative of memory and parental love, Richard Ford tells of his mother, Edna, a feisty Catholic girl with a difficult past, and his father, Parker, a sweet-natured soft-spoken traveling salesman, both born at the turn of the twentieth century in rural Arkansas. -

HUMAN REALITY UNCOVERED in the ALIEN: HEPTAPOD LANGUAGE in “STORY of YOUR LIFE” and ARRIVAL Entry for the Betty G

HUMAN REALITY UNCOVERED IN THE ALIEN: HEPTAPOD LANGUAGE IN “STORY OF YOUR LIFE” AND ARRIVAL Entry for the Betty G. Headley Senior Essay Award By Julianna Suderman 1 Human Reality Uncovered in the Alien: Heptapod Language in “Story of Your Life” and Arrival The notion that language has a connection to our existence, rather than simply being a tool or arbitrary set of signs, is vital to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which proposes that our language can alter the way we think. Ted Chiang takes this hypothesis to the point where language alters our very perception of reality in his novella “Story of Your Life,” which was recently adapted into the film Arrival. In both versions of the story, the protagonist, linguist Dr. Louise Banks, begins to view time from a simultaneous, rather than sequential point of view, simply by learning the language of “heptapods.” These aliens, who hover above Earth in their ovular ships, seem to experience reality outside of time as we know it. While the story approaches its premise from a modern viewpoint that language is a tool, or even a weapon, its fantastical representation of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis implies that the way language exists deep within the mind fundamentally changes our perception of, and participation in, reality itself. Such a representation of language hearkens back to the ontotheological synthesis that is foundational to the works of Augustine and Aquinas. Paradoxically, in regaining this worldview, the ability to become more like the aliens allows the human protagonist to become more human in an ontotheological sense. Debates about the use and nature of language are at the forefront throughout “Story of Your Life” and Arrival. -

The End of Books—Or Books Without End? Front.Qxd 11/15/1999 9:04 AM Page Ii Front.Qxd 11/15/1999 9:04 AM Page Iii

front.qxd 11/15/1999 9:04 AM Page i The End of Books—or Books without End? front.qxd 11/15/1999 9:04 AM Page ii front.qxd 11/15/1999 9:04 AM Page iii The End of Books—Or Books without End? Reading Interactive Narratives J. Yellowlees Douglas Ann Arbor The University of Michigan Press front.qxd 11/15/1999 9:04 AM Page iv Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2000 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2003 2002 2001 2000 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0-472-11114-0 (cloth: alk. paper) front.qxd 11/15/1999 9:04 AM Page v Acknowledgments In 1986 John McDaid, then a fellow graduate student at New York University, suggested I meet Jay Bolter, who arrived bearing a 1.0 beta copy of Storyspace. When he opened the Storyspace demo document to show McDaid and I a cognitive map of the Iliad represented as a hypertext, my fate was clinched in under sixty seconds. I had seen the future, and it consisted of places, paths, links, cognitive maps, and a copy of afternoon, a story, which Jay also gave us.