The End of Books—Or Books Without End? Front.Qxd 11/15/1999 9:04 AM Page Ii Front.Qxd 11/15/1999 9:04 AM Page Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAR Interpretive Report Sample

Interpretive Report by Steven G. Feifer, DEd, Rebecca Gerhardstein Nader, PhD, and PAR Staff Client Information Client name: Sample Client Client ID : LD Test date : 05/12/2017 Date of birth : 11/10/2009 Age : 7:6 Grade/Education: 2nd Gender : Female Examiner : Dr Williams This report is intended for use by qualified professionals only and is not to be shared with the student or any other unqualified persons. Sample Client Page 1 Interpretive Report 05/12/2017 Overview of This Report The Feifer Assessment of Reading (FAR) is an individually administered measure of reading ability normed for students in prekindergarten through college. The FAR contains individual tests of reading skills which are combined to form a Phonological Index (PI), a Fluency Index (FI), and a Comprehension Index (CI). The subtests which compose the PI assess phonological processing and decoding skills of words in isolation as well as in context. The FI is comprised of subtests that assess visual perception and orthographic processing of letters and words, as well as fluidity in pronouncing phonologically-irregular words. The CI contains subtests designed to assess the underlying factors involved in deriving meaning from print. The Mixed Index (MI), calculated by combining the PI and the FI, assesses for deficits in both phonological processing and orthographic processing skills. The FAR Total Index (TI), calculated by combining the PI, FI, and CI subtests, provides the most comprehensive and reliable assessment of overall reading proficiency. Each index score is expressed as a grade-corrected standard score scaled to a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. -

Tunnels, Deeper, Freefall, and Closer by Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams

READING GROUP GUIDE Tunnels, Deeper, Freefall, and closer by Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams Enter the terrifying world of Tunnels—a subterranean society under the streets of modern London, whose citizens are enslaved by a strange, cruel sect, the Styx, who plan to exterminate all Topsoilers. Can fourteen-year-old Will defeat the Styx, and rescue his missing father? Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams first met at college in London and have remained friends ever since. Gordon, a former investment banker, now lives with his wife and children in Norfolk, England; Williams, an installation artist, inhabits the city’s Hackney neighborhood, accompanied everywhere by his invisible dog. About their writing process, Gordon says: “When I lived in London, my house was only a ten-minute bike ride from where Brian lived, so he’d cycle round and we would work on Tunnels at my kitchen table. When I moved with my family to the country, we discussed Deeper over many late-night phone calls, and swapped sections by email. When I visit London we go to a couple of favorite cafés. They’ve gotten used to us and know that we can make a cup of coffee last several hours!” Tunnels A New York Times Bestseller About the book He’s a loner at school, his sister’s beyond bossy, and his mother watches TV all day long, but at least Will Burrows shares one hobby with his otherwise weird father: They’re both obsessed with archeological sites. When the two discover an abandoned tunnel buried below modern London, they think they’re on the brink of a major find. -

List of Different Digital Practices 3

Categories of Digital Poetics Practices (from the Electronic Literature Collection) http://collection.eliterature.org/1/ (Electronic Literature Collection, Vol 1) http://collection.eliterature.org/2/ (Electronic Literature Collection, Vol 2) Ambient: Work that plays by itself, meant to evoke or engage intermittent attention, as a painting or scrolling feed would; in John Cayley’s words, “a dynamic linguistic wall- hanging.” Such work does not require or particularly invite a focused reading session. Kinetic (Animated): Kinetic work is composed with moving images and/or text but is rarely an actual animated cartoon. Transclusion, Mash-Up, or Appropriation: When the supply text for a piece is not composed by the authors, but rather collected or mined from online or print sources, it is appropriated. The result of appropriation may be a “mashup,” a website or other piece of digital media that uses content from more than one source in a new configuration. Audio: Any work with an audio component, including speech, music, or sound effects. CAVE: An immersive, shared virtual reality environment created using goggles and several pairs of projectors, each pair pointing to the wall of a small room. Chatterbot/Conversational Character: A chatterbot is a computer program designed to simulate a conversation with one or more human users, usually in text. Chatterbots sometimes seem to offer intelligent responses by matching keywords in input, using statistical methods, or building models of conversation topic and emotional state. Early systems such as Eliza and Parry demonstrated that simple programs could be effective in many ways. Chatterbots may also be referred to as talk bots, chat bots, simply “bots,” or chatterboxes. -

A Guide to the Josh Brandt Video Game Collection Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute DigitalCommons@WPI Collection Guides CPA Collections 2014 A guide to the Josh Brandt video game collection Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/cpa-guides Suggested Citation , (2014). A guide to the Josh Brandt video game collection. Retrieved from: http://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/cpa-guides/4 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the CPA Collections at DigitalCommons@WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collection Guides by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WPI. Finding Aid Report Josh Brandt Video Game Collection MS 16 Records This collection contains over 100 PC games ranging from 1983 to 2002. The games have been kept in good condition and most are contained in the original box or case. The PC games span all genres and are playable on Macintosh, Windows, or both. There are also guides for some of the games, and game-related T-shirts. The collection was donated by Josh Brandt, a former WPI student. Container List Container Folder Date Title Box 1 1986 Tass Times in Tonestown Activision game in original box, 3 1/2" disk Box 1 1989 Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - Curse of the Azure Bonds 5 1/4" discs, form IBM PC, in orginal box Box 1 1988 Life & Death: You are the Surgeon 3 1/2" disk and related idtems, for IBM PC, in original box Box 1 1990 Spaceward Ho! 2 3 1/2" disks, for Apple Macintosh, in original box Box 1 1987 Nord and Bert Couldn't Make Heads or Tails of It Infocom, 3 1/2" discs, for Macintosh in original -

Subvocalization – Toward Hearing the Inner Thoughts of Developers

2011 19th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension Subvocalization – Toward Hearing the Inner Thoughts of Developers Chris Parnin College of Computing Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, Georgia USA [email protected] Abstract—Some of the most fascinating feats of cognition any significant effects hoping to be found when evaluating are never witnessed or heard by others, yet they occur daily a new tool. With instrumentation data, experimenters have in the minds of software developers practicing their craft. recorded actions, but little context and must substitute cog- Researchers have desperately tried to glimpse inside, but with limited tools, the view into a developer’s internal mental pro- nitive measures such as cognitive effort or memory retention cesses has been dim. One available tool, so far overlooked but with metrics such as ratio of document navigations to edits widely used, has demonstrated the ability to measure the phys- or frequency of revisiting a method. Talk-aloud protocols, iological correlates of cognition. When people perform complex like surveys, rely on self-reporting and require considerable tasks, sub-vocal utterances (electrical signals sent to the tongue, manual transcription and analysis that garner valuable but lips, or vocal cords) can be detected. This phenomenon has long intrigued researchers, some likening sub-vocal signals to indefinite and inconsistent insight. the conduits of our thoughts. Recently, researchers have even Within the past few decades, modern research disci- been able to decode these signals into words. In this paper, plines, such as psychology and cognitive neuroscience, have we explore the feasibility of using this approach and report collectively embraced methods that measure physiological our early results and experiences in recording electromyogram correlates of cognition as a standard practice. -

Starship Titanic: a Novel Free

FREE STARSHIP TITANIC: A NOVEL PDF Douglas Adams,Terry Jones | 246 pages | 10 Sep 2009 | Random House USA Inc | 9780345368430 | English | New York, United States Douglas Adams's Starship Titanic by Terry Jones: | : Books Look Inside. Arguably the greatest collaboration in the whole history of comedy! Terry Jones of Monty Python wrote the book. In the nude! Parents be warned! Most of the words Starship Titanic: A Novel this book were Starship Titanic: A Novel by a naked man! You want to argue with that? All right, we give in. Starship Titanic is the greatest, most fabulous, most technologically advanced interstellar Starship Titanic: A Novel line ever built. Furthermore, it cannot possibly go wrong. And disappears. Coming home that night, on a little known planet called Earth, Dan and Lucy Gibson find something very large and very, very shiny sticking into their house. The saga of "the ship that cannot possibly go wrong" sparkles with wit, danger, and confusion that will keep readers Starship Titanic: A Novel which reality they are in and how, on earth, to find their way out again. At the center of the galaxy, a vast, unknown civilization is preparing for an event of epic proportions: the launching of the greatest, most gorgeous, most technologically advanced Starship ever built-the Starship Titanic. An earthling would see it as a mixture of the Starship Titanic: A Novel Building, the tomb of Tutankhamen, and Venice. He is an old man now, and the creation of the Starship Titanic is the pinnacle achievement of his twenty-year career. The night before the launch, Leovinus is prowling around the ship having a last little look. -

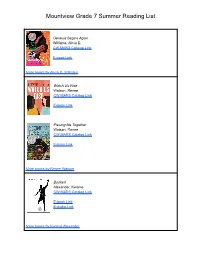

Mountview Grade 7 Summer Reading List

Mountview Grade 7 Summer Reading List Genesis Begins Again Williams, Alicia D. CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link More books by Alicia D. Williams Watch Us Rise Watson, Renee CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link Piecing Me Together Watson, Renee CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link More books by Renee Watson Booked Alexander, Kwame CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link E-audio Link More books by Kwame Alexander Harbor Me Woodson, Jacqueline CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link E-audio Link More books by Jacqueline Woodson Shipwreck at the Bottom of the World Armstrong, Jennifer CW MARS Catalog Link E-audio Link More books by Jennifer Armstrong Tiger, Tiger Banks, Lynn Reis CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link More books by Lynn Reis Banks Black Potatoes: the story of the great irish famine Bartoletti, Susan CW MARS Catalog Link More books by Susan Bartoletti Let me Play: the story of Title IX Blumenthal, Karen CW MARS Catalog Link More books by Karen Blumenthal I’d Tell you I Love you, but then I’d have to Kill you (Gallagher Girls, Book 1) Carter, Ally CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link Other books in series: Cross my Heart and Hope to Spy (Gallagher Girls, Book 2) ● E-book Don’t Judge a Girl by her Cover (Gallagher Girls, Book 3) ● E-book Only the Good Spy Young (Gallagher Girls, Book 4) ● E-book Out of Sight, Out of Time (Gallagher Girls, Book 5) ● E-book United we Spy (Gallagher Girls, Book 6) ● E-book More books by Ally Carter The Red Kayak Cummings, Priscilla CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link Other books in series: The Journey Back ● E-book Cheating for the Chicken Man ● E-book More books by Priscilla Cummings The Fire Within (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 1) D'Lacey, Chris CW MARS Catalog Link E-book Link Other books in series: Icefire (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 2) ● E-book Firestar (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 3) The Fire Eternal (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 4) Dark Fire (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 5) Fire World (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 6) The Fire Ascending (Last Dragon Chronicles, Book 7) More books by Chris D’Lacey Guinea Pig Scientists Dendy, Leslie A. -

Screening a Digital Visual Poetics

Screening a Digital Visual Poetics Brian Lennon Columbia University Book was there, it was there. Gertrude Stein “O sole mio.” The contemporary elegy, Peter M. Sacks has observed, mourns not only the deceased but also the ceremony or medium of grief itself.1 Recent trends in digital media theory signal the absorp- tion of initial, utopian claims made for electronic hypertextuality and for the transformation of both quotidian and literary discourse via the radical enfranchisement of active readers. Born in 1993, the democratizing, decentralizing World Wide Web—at first, the “almost embarrassingly literal embodiment” (George P. Landow) of post- structuralist literary theory, a global Storyspace—has in a mere six years been appropriated, consolidated, and “videated” as a forum for commerce and advertising.2 Meanwhile, with the public recantation 1. Peter M. Sacks, The English Elegy: Studies in the Genre from Spenser to Yeats (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), p. 299: “Sociologists and psychologists, as well as literary and cultural historians, consistently demonstrate the ways in which death has tended to become obscene, meaningless, impersonal—an event either stupefyingly colossal in cases of large-scale war or genocide, or clinically concealed somewhere be- hind the technology of the hospital and the techniques of the funeral home.” It is the technology, of course, that is key: and this applies not just to the technologically ob- scured death of human bodies, but to the technologically assisted figural “death,” first of the author (Barthes, Foucault), then of the printed book (Birkerts et al.), and now of the techno-socialistic “network” (with military antecedents) that the Internet once was. -

<I>Victory Garden</I>

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 8-2012 Reading Ineffability and Realizing Tragedy in Stuart Moulthrop's Victory Garden Michael E. Gray Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gray, Michael E., "Reading Ineffability and Realizing Tragedy in Stuart Moulthrop's Victory Garden" (2012). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1188. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1188 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. READING INEFFABILITY AND REALIZING TRAGEDY IN STUART MOULTHROP’S VICTORY GARDEN A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Michael E. Gray August 2012 I would like to thank my wife, Lisa Oliver-Gray, for her steadfast support during this project. Without her love and the encouragement of my family and friends, I could not have finished. I would also like to thank my committee for their timely assistance this summer. Last, I would like to dedicate this labor to my father, Dr. Elmer Gray, who quietly models academic excellence and was excited to read a sprawling first draft. CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..1-30 Chapter One…………………………………………………………………………31-57 Chapter Two…………………………………………………………………………58-86 Chapter Three………………………………………………………………………87-112 Appendix: List of Screenshots...………………………………………………….113-121 Notes………………………………………………………………………………122-145 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………….146-149 iv TABLE OF FIGURES Figure 1. -

The Smashwords Book Marketing Guide

The Smashwords Book Marketing Guide Copyright 2008-2012 Mark Coker, Founder of Smashwords (http://www.smashwords.com) Version 1.18 Updated 12.9.12 ~~**~~ Smashwords Edition Cover design by PJ Lyon ~~**~~ Other Smashwords Titles by Mark Coker: The Smashwords Style Guide (how to format an ebook) The Secrets to Ebook Publishing Success (ebook publishing best practices) The 10-Minute PR Checklist – How to Earn the Publicity You Deserve Boob Tube (novel about Hollywood celebrity) ~~**~~ Table of Contents Introduction: About the Smashwords Book Marketing Guide Background on Smashwords Setting expectations How Smashwords helps authors and publishers market books Adopting a proactive marketing mindset Marketing starts now Hyperlinks help readers discover books The importance of authors helping authors 37 Marketing Tips (all free to implement!) Tip #1 – Update your email signature Tip #2 – Post a notice on your web site or blog Tip #3 – Contact your friends, family, co-workers and fans Tip #4 – Post a notice to your social networks Tip #5 – Update your message board signatures Tip #6 – How to reach readers with Twitter Tip #7 – Publish more than one book to create a multiplier effect Tip #8 – Advertise your other books in each book you publish Tip #9 – Make it easy for your readers to connect with you Tip #10 – Issue a press release on a free PR wire service Tip #11 – Join HARO, Help-a-reporter-online for free press leads Tip #12 – Encourage fans to purchase and review your book Tip #13 – Write thoughtful reviews for other books Tip #14 – Participate -

Characters and Characterisation in Durrell's the Alexandria Quartet

CHARACTERS AND CHARACTERISATION IN DURRELL'S THE ALEXANDRIA QUARTET Dr. Anna Pratt When The Alexandria Quartet appeared in the late fifties (Justine 1957; Balthazar 1958; Mountolive 1958; Clea 1960) it was given a very mixed reception. Some critics were enthusiastic, making sometimes exaggerated claims for Durrell's originality and greatness; others were more sceptical. George Steiner for instance praised the richness of Durrell's style, saying : "No one else writing in English today has a comparable command of the light and music of language ... Who is to say ... that The Alexandria Quartetwill not lead to a 1 renascence of prose" ? ( ) , while Angus Wilson disagreed, claiming that "Durrell's aims are magnificent, but his execution is often slipshod and pretentious, and the language floridly vul 2 gar" . ( ) It is interesting to note that Durrell's most severe critics tended to be British, and his popularity was much greater in America and on the Continent than in his own country. Dur rell's biographer, G.S. Fraser, says that the prevailing view in England was that the Alexan dria Quartet "is a most impressive but in some ways flawed or imperfect work, extraordinarily 3 vivid, but too rich, too gaudy" . ( ) A similar difference of opinion can be noticed in critical comments on Durrell's methods of characterisation and his ability to create convincing characters. Here again, most British critics were not impressed by characters in The Quartet . The following quotations illustrate the dominant attitude : "For the most part the characters in these novels remain flat surfaces . .. they never become three-dimensional figures .. -

Indian Metaphysics in Lawrence Durrell's Novels

Indian Metaphysics in Lawrence Durrell’s Novels Indian Metaphysics in Lawrence Durrell’s Novels By C. Ravindran Nambiar Indian Metaphysics in Lawrence Durrell’s Novels, by C. Ravindran Nambiar This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by C. Ravindran Nambiar All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5315-1, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5315-6 Dedicated to my wife Prabha I know that the bone structure of my work is metaphysically solid, so to speak, and that’s what counts. —Lawrence Durrell TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. viii Foreword .................................................................................................... xi Dr. Corinne Alexandre-Garner Introduction ............................................................................................. xvii Prof. Ian S. MacNiven List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xxii Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Durrell