Volume 1 Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

The Girl in the Woods: on Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 10 Issue 1 J.R.R. Tolkien and the works of Joss Article 3 Whedon 2020 The Girl in the Woods: On Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror Brendan Anderson University of Vermont, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Recommended Citation Anderson, Brendan (2020) "The Girl in the Woods: On Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol10/iss1/3 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christopher Center Library at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Anderson: The Girl in the Woods THE GIRL IN THE WOODS: ON FAIRY STORIES AND THE VIRGIN HORROR INTRODUCTION The story is an old one: the maiden, venturing out her door, ignores her guardian’s prohibitions and leaves the chosen path. Fancy draws her on. She picks the flow- ers. She revels in her freedom, in the joy of being young. Then peril appears—a wolf, a monster, something with teeth for gobbling little girls—and she learns, too late, there is more to life than flowers. The girl is destroyed, but then—if she is lucky—she returns a woman. According to Maria Tatar (while quoting Catherine Orenstein): “the girl in the woods embodies ‘complex and fundamental human concerns’” (146), a state- ment at least partly supported by its appearance in the works of both Joss Whedon and J.R.R. -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

Wavebid > Buyers Guide

Auction Catalog April25-May 2 Auction 2021 - Date Posted is When Online Auction Date: Sunday, Apr 25 2021 Bidding Starts: 10:00 AM EDT Granny's Auction House Phone: (727) 572-1567 5175 Ulmerton Rd Email: grannysauction@gmail. Ste B com Clearwater, FL 33760 © 2021 Granny's Auction House 04/26/2021 05:10 PM Lot Title & Description Number 1 1994 Florence Limited Ed. Walt Disney's Ariel Figurine by Giuseppe Armani - made in Italy #1623/1500 (great condition) {in house shipping available} Mixed Metal Los Castillo Taxco Mexico Tipping Inlaid Hard Stone Bird Pitcher - 6 1/4" tall, 4 1/2" wide with handle, maker mark on 2 bottom, {in house shipping available} Franklin Mint Star Trek Starship Enterprise Ship - pewter ships on stands, authorized by Paramount Pictures (one arm of ship has 3 started to pull away from ship and both arms are bent down) {in house shipping available} Spectacular 1998 Vincent Trabucco Art Glass Paperweight - beautiful detailed floral design on white lace - signed on bottom {in house 4 shipping available} Mt Washington Peachblow JIP Tulip and Enameled Blue Glass Victorian Vases - 8" rib optic Victorian blue glass vase with black 5 cartouche enamel decoration surrounding raised gold bird scenic and additional floral decorations, 9" slender tulip lip vase with classic Mt Washington soft white to blush satin body - in house shipping available 6 Lalique Satin Finish Sparrow and Accented Filicaria vase - 4.5" Filicaria with fern like leaf cuttings in original box and 3" x 4.5" sparrow (no box) - in house shipping available Steiff Quality European Construction Vintage Mohair Stuffed 3 Piece Showroom Size Deer Family - 36" high buck with head raised and sewn leather 10 point antler rack, 20" tall momma deer with big eye lashes and head lowered to the side, and 13" fawn with head 7 raised to nuzzle with momma - European construction, they all have beautiful mohair coats over sturdy frame, tan underbellies and air brushed spotted coats, leather hooves and glass eyes. -

London Contemporary Orchestra: Other Worlds Wednesday 31 October 2018 8Pm, Hall

London Contemporary Orchestra: Other Worlds Wednesday 31 October 2018 8pm, Hall Giacinto Scelsi Uaxuctum: The Legend of the Maya City, destroyed by the Maya people themselves for religious reasons UK premiere interval 20 minutes John Luther Adams Become Ocean London Contemporary Orchestra and Choir Robert Ames conductor Universal Assembly Unit art direction Artrendex artificial intelligence London Contemporary Orchestra and Universal Assembly Unit are grateful to Arts Council England for their support for the visual elements of this concert Part of Barbican Presents 2018–19 Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel 020 3603 7930) Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. Please remember that to use our induction loop you should switch your hearing aid to T setting on entering the hall. If your hearing aid is not correctly set to T it may cause high-pitched feedback which can spoil the enjoyment of your fellow audience members. We appreciate that it’s not always possible to prevent coughing during a performance. But, for the sake of other audience members and the artists, if you feel the need to cough or sneeze, please stifle it with a handkerchief. The City of London If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know Corporation is the founder and during your visit. Additional feedback can be given principal funder of online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods the Barbican Centre located around the foyers. -

Cultural Stereotypes: from Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions Ileana F. Popa Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Ileana Florentina Popa BA, University of Bucharest, February 1991 MA, Virginia Commonwealth University, May 2006 Director: Marcel Cornis-Pope, Chair, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2006 Table of Contents Page Abstract.. ...............................................................................................vi Chapter I. About Stereotypes and Stereotyping. Definitions, Categories, Examples ..............................................................................1 a. Ethnic stereotypes.. ........................................................................3 b. Racial stereotypes. -

Download (4MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Emperor’s New Clothes” Manoeuvre Warfare and Operational Art Nils Jorstad Thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Department of Modem History University of Glasgow April 2004 ©Nils Jorstad 2004 ProQuest N um ber: 10390751 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10390751 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). C o pyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. -

THOTKG Production Notes Final REVISED FINAL

SCREEN AUSTRALIA, LA CINEFACTURE and FILM4 Present In association with FILM VICTORIA ASIA FILM INVESTMENT GROUP and MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL A PORCHLIGHT FILMS and DAYBREAK PICTURES production true history of the Kelly Gang. GEORGE MACKAY ESSIE DAVIS NICHOLAS HOULT ORLANDO SCHWERDT THOMASIN MCKENZIE SEAN KEENAN EARL CAVE MARLON WILLIAMS LOUIS HEWISON with CHARLIE HUNNAM and RUSSELL CROWE Directed by JUSTIN KURZEL Produced by HAL VOGEL, LIZ WATTS JUSTN KURZEL, PAUL RANFORD Screenplay by SHAUN GRANT Based on the Novel by PETER CAREY Executive Producers DAVID AUKIN, VINCENT SHEEHAN, PETER CAREY, DANIEL BATTSEK, SUE BRUCE-SMITH, SAMLAVENDER, EMILIE GEORGES, NAIMA ABED, RAPHAËL PERCHET, BRAD FEINSTEIN, DAVID GROSS, SHAUN GRANT Director of Photography ARI WEGNER ACS Editor NICK FENTON Production Designer KAREN MURPHY Composer JED KURZEL Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Sound Designer FRANK LIPSON M.P.S.E. Hair and Make-up Designer KIRSTEN VEYSEY Casting Director NIKKI BARRETT CSA, CGA SHORT SYNOPSIS Inspired by Peter Carey’s Man Booker prize winning novel, Justin Kurzel’s TRUE HISTORY OF THE KELLY GANG shatters the mythology of the notorious icon to reveal the essence behind the Life of Ned KeLLy and force a country to stare back into the ashes of its brutal past. Spanning the younger years of Ned’s Life to the time Leading up to his death, the fiLm expLores the bLurred boundaries between what is bad and what is good, and the motivations for the demise of its hero. Youth and tragedy colLide in the KeLLy Gang, and at the beating heart of this tale is the fractured and powerful Love story between a mother and a son. -

LES OUBLIÉS DE LA BATAILLE D'angleterre LA RAF Attaque

4 LES OUBLIÉS DE LA BATAILLE D’ANGLETERRE LA RAF ATTAQUE LES PORTS DE LA MANCHE LES OUBLIÉS DE LA BATAILLE D’ANGLETERRE LA RAF attaQUE LES Ports DE LA MANCHE (DE LA CHUTE DE LA FRANCE À LA FIN DE LA Bataille D’ANGLETERRE) (Fin juin-décembre 1940) J-L Roba Pour la quasi-totalité du public, toute l’activité de l’aviation militaire britannique en 1940 après la chute de la France se résume en la seule Bataille d’Angleterre avec ses ‘Few’ du Fighter Command, popularisés par une prose très nombreuse. Dans son ouvrage ‘The other Few’, Larry Donnelly a tenté de rappeler les combats oubliés de cette période menés par les deux autres branches de la RAF : les Bomber et Coastal Commands ainsi que leurs pertes trop souvent passées sous silence. Les actions des aviateurs d’Outre-Manche ne se résumèrent donc pas en des duels mortels sur l’Angleterre (avec, comme il se doit, l’aide primordiale de l’appareillage Ultra !) puisque, quittant l’espace aérien du Royaume-Uni et traversant le ‘Channel’, des équipages de Blenheim, Battle, Hampden, Wellington, … allaient revenir sur la Belgique, les Pays-Bas et la France - nations évacuées à la fin mai 1940 – cela pour tenter au péril de leur vie de harceler l’adversaire dans des opérations aussi ingrates qu’éprouvantes. Ce texte ne va développer que les seules opérations de la RAF sur l’Hexagone. Le lecteur ne devra dès lors pas perdre de vue que, concomitamment, cette même RAF envoya également ses bombardiers sur d’autres pays occupés (Scandinavie y compris) dispersant ainsi largement ses appareils. -

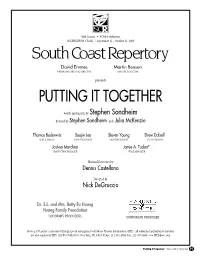

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Show Programs

~ 52ND STREET PROJECT SHOW PROGRAMS 1996-2000 r JJj!J~f~Fffr!JFIEJ!fJE~JJf~fJ!iJrJtrJffffllj'friJfJj[IlJ'JiJJif~ i i fiiii 1 t!~~~~fi Jf~[fi~~~r~j (rjl 1 rjfi{Jij(fr; 1 !liirl~iJJ[~JJJf J Jl rJ I frJf' I j tlti I ''f '!j!Udfl r r.~~~.tJI i ~Hi 'fH '~ r !!'!f'il~ [ Uffllfr:pllfr!l(f[J'l!'Jlfl! U!! ~~frh:t- G 1 1 lr iJ!•f Hlih rfiJ aflfiJ'jrti lf!liJhi!rHdiHIIf!ff tl~

1 Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY of CONGRESS

Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS In the Matter of Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies Under 17 U.S.C. §1201 Docket No. 2014-07 Reply Comments of the Electronic Frontier Foundation 1. Commenter Information Mitchell L. Stoltz Corynne McSherry Kit Walsh Electronic Frontier Foundation 815 Eddy St San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is a member-supported, nonprofit public interest organization devoted to maintaining the traditional balance that copyright law strikes between the interests of rightsholders and the interests of the public. Founded in 1990, EFF represents over 25,000 dues-paying members, including consumers, hobbyists, artists, writers, computer programmers, entrepreneurs, students, teachers, and researchers, who are united in their reliance on a balanced copyright system that ensures adequate incentives for creative work while promoting innovation, freedom of speech, and broad access to information in the digital age. In filing these reply comments, EFF represents the interests of the many people in the U.S. who have “jailbroken” their cellular phone handsets and other mobile computing devices—or would like to do so—in order to use lawfully obtained software of their own choosing, and to remove software from the devices. 2. Proposed Class 16: Jailbreaking – wireless telephone handsets Computer programs that enable mobile telephone handsets to execute lawfully obtained software, where circumvention is accomplished for the sole purposes of enabling interoperability of such software with computer programs on the device or removing software from the device. 1 3.