Stanford University 450 Jane Stanford Way, Building 10 Stanford, CA 94305 RE: Free Speech at Stanford University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stanford Daily an Independent Newspaper

The Stanford Daily An Independent Newspaper VOLUME 199, NUMBER 36 99th YEAR MONDAY, APRIL 15, 1991 Electronic mail message may be bylaws violation By Howard Libit Staff writer Greek issues Over the weekend, campaign violations seemed to be the theme of the Council of Presidents and addressed in ASSU Senate races. Hearings offi- cer Jason Moore COP debate said the elec- By MirandaDoyle tions commis- Staff writer sion will look into vio- possible Three Council of Presi- lations by Peo- dents slates debated at the pie's Platform Sigma house last candidatesand their supporters of Kappa night, answering questions several election bylaws that ranging from policies revolve around campaigning toward Greek organizations through electronic mail. to the scope ofASSU Senate Students First also complained debate. about the defacing and removing Beth of their fliers. The elec- Morgan, a Students of some First COP said will be held Wednesday and candidate, tion her slate plans to "fight for Thursday. new houses to be built" for Senate candidate Nawwar Kas- senate fraternities and work on giv- rawi, currently a associate, ing the Interfraternity sent messages yesterday morning Council and the Intersoror- to more than 2,000 students via ity Council more input in electronic urging support for mail, decisions concerning frater- the People's Platform COP Rajiv Chandrasekaran — Daily "Stand and Deliver" senate nities and sororities. First lady Barbara Bush was one of many celebrities attending this weekend's opening ceremonies for the Lucile Salter Packard Chil- slate, member ofthe candidates and several special fee MaeLee, a dren's Hospital. She took time out from a tour of the hospital to meet two patients, Joshua Evans, 9, and Shannon Brace, 4. -

2012 Tour Slides

1 Welcome! LINAC: Linear Accelerator It has driven SLAC science for 50 years 2 Department of Energy Office of Science National Laboratories Idaho National Laboratory Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Pacific Northwest Laboratory National Energy Technology Laboratory Ames National Brookhaven Laboratory National Lawrence Livermore National Renewable Laboratory Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Energy Laboratory National Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory Laboratory Argonne National Laboratory Thomas Jefferson SLAC National National Accelerator Facility Accelerator Los Alamos Laboratory Oak Ridge National National Laboratory Laboratory Sandia National Laboratories Savannah River National Laboratory National Nuclear Security Administration Lab Office of Fossil Energy Lab Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Lab Office of Nuclear Energy, Science and Technology Lab Office of Environmental Management Lab Office of Science Lab 3 Stanford University DOE pays Stanford $1 per year to lease 426 acres of land 240 Universities worldwide use our resources 4 1,663 Employees from 36 Countries -205 Postdocs and Grad Students ; 3,100 Facility Users & Visiting Scientists 142 Buildings 1,000 Scientific Papers published each year in peer-reviewed journals 6 Scientists awarded the Nobel Prize for work done at SLAC 1st North American Website $350,000,000 Budget (10% of this goes for energy consumption) Jan 26, 2012 5 Our Directors through the years: 1961-1984 1984-1999 1999-2007 Wolfgang “Pief” Burton Richter Jonathan Dorfan Panofsky 2007-Present -

Hoover Digest

HOOVER DIGEST RESEARCH + OPINION ON PUBLIC POLICY SUMMER 2020 NO. 3 HOOVER DIGEST SUMMER 2020 NO. 3 | SUMMER 2020 DIGEST HOOVER THE PANDEMIC Recovery: The Long Road Back What’s Next for the Global Economy? Crossroads in US-China Relations A Stress Test for Democracy China Health Care The Economy Foreign Policy Iran Education Law and Justice Land Use and the Environment California Interviews » Amity Shlaes » Clint Eastwood Values History and Culture Hoover Archives THE HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace was established at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, a member of Stanford’s pioneer graduating class of 1895 and the thirty-first president of the United States. Created as a library and repository of documents, the Institution approaches its centennial with a dual identity: an active public policy research center and an internationally recognized library and archives. The Institution’s overarching goals are to: » Understand the causes and consequences of economic, political, and social change The Hoover Institution gratefully » Analyze the effects of government actions and public policies acknowledges gifts of support » Use reasoned argument and intellectual rigor to generate ideas that for the Hoover Digest from: nurture the formation of public policy and benefit society Bertha and John Garabedian Charitable Foundation Herbert Hoover’s 1959 statement to the Board of Trustees of Stanford University continues to guide and define the Institution’s mission in the u u u twenty-first century: This Institution supports the Constitution of the United States, The Hoover Institution is supported by donations from individuals, its Bill of Rights, and its method of representative government. -

Sidney D. Drell Professional Biography

Sidney D. Drell Professional Biography Present Position Professor Emeritus, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University (Deputy Director before retiring in 1998) Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution since 1998 Present Activities Member, JASON, The MITRE Corporation Member, Board of Governors, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel Professional and Honorary Societies American Physical Society (Fellow) - President, 1986 National Academy of Sciences American Academy of Arts and Sciences American Philosophical Society Academia Europaea Awards and Honors Prize Fellowship of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, November (1984-1989) Ernest Orlando Lawrence Memorial Award (1972) for research in Theoretical Physics (Atomic Energy Commission) University of Illinois Alumni Award for Distinguished Service in Engineering (1973); Alumni Achievement Award (1988) Guggenheim Fellowship, (1961-1962) and (1971-1972) Richtmyer Memorial Lecturer to the American Association of Physics Teachers, San Francisco, California (1978) Leo Szilard Award for Physics in the Public Interest (1980) presented by the American Physical Society Honorary Doctors Degrees: University of Illinois (1981); Tel Aviv University (2001), Weizmann Institute of Science (2001) 1983 Honoree of the Natural Resources Defense Council for work in arms control Lewis M. Terman Professor and Fellow, Stanford University (1979-1984) 1993 Hilliard Roderick Prize of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Science, Arms Control, and International Security 1994 Woodrow Wilson Award, Princeton University, for “Distinguished Achievement in the Nation's Service” 1994 Co-recipient of the 1989 “Ettore Majorana - Erice - Science for Peace Prize” 1995 John P. McGovern Science and Society Medalist of Sigma Xi 1996 Gian Carlo Wick Commemorative Medal Award, ICSC–World Laboratory 1997 Distinguished Associate Award of U.S. -

An Analysis of Vice President Biden's Economic Agenda

A HOOVER INSTITUTION STUDY An Analysis of Vice President Biden’s Economic Agenda: The Long Run Impacts of Its Regulation, Taxes, and Spending* Institution Hoover TIMOTHY FITZGERALD, KEVIN HASSETT, CODY KALLEN, AND CASEY B. MULLIGAN We estimate possible effects of Joe Biden’s tax and regulatory agenda. We find that transportation and electricity will require more inputs to produce the same outputs due to ambitious plans to further cut the nation’s carbon emissions, resulting in one or two percent less total factor productivity nationally. Second, we find that proposed changes to regulation as well as to the ACA increase labor wedges. Third, Biden’s agenda increases average marginal tax rates on capital income. Assuming that the supply of capital is elastic in the long run to its after-tax return and that the substitution effect of wages on labor supply is nontrivial, we conclude that, in the long run, Biden’s full agenda reduces full- time equivalent employment per person by about 3 percent, the capital stock per person by about 15 percent, real GDP per capita by more than 8 percent, and real consumption per household by about 7 percent. I. Introduction Advancing equality, environmental protection and other social goals involves tradeoffs. The purpose of this paper is to quantify possible economic effects of the Biden agenda. Vice President Biden proposes to • reverse some of the 2017 tax cuts as well as increase the taxation of corporations and high-income households and pass through entities; • reverse much of the regulatory reform of the past three years as well as setting new environmental standards; and • create or expand subsidies for, especially, health insurance and renewable energy. -

Sidney D. Drell 1926–2016

Sidney D. Drell 1926–2016 A Biographical Memoir by Robert Jaffe and Raymond Jeanloz ©2018 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. SIDNEY daVID DRELL September 13, 1926–December 21, 2016 Elected to the NAS, 1969 Sidney David Drell, professor emeritus at Stanford Univer- sity and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, died shortly after his 90th birthday in Palo Alto, California. In a career spanning nearly 70 years, Sid—as he was universally known—achieved prominence as a theoretical physicist, public servant, and humanitarian. Sid contributed incisively to our understanding of the elec- tromagnetic properties of matter. He created the theory group at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) and led it through the most creative period in elementary particle physics. The Drell-Yan mechanism is the process through which many particles of the Standard Model, including the famous Higgs boson, were discovered. By Robert Jaffe and Raymond Jeanloz Sid advised Presidents and Cabinet Members on matters ranging from nuclear weapons to intelligence, speaking truth to power but with keen insight for offering politically effective advice. His special friendships with Wolfgang (Pief) Panofsky, Andrei Sakharov, and George Shultz highlighted his work at the interface between science and human affairs. He advocated widely for the intellectual freedom of scientists and in his later years campaigned tirelessly to rid the world of nuclear weapons. Early life1 and work Sid Drell was born on September 13, 1926 in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on a small street between Oriental Avenue and Boardwalk—“among the places on the Monopoly board,” as he was fond of saying. -

A Look at Upcoming Exhibits and Performances Page 34

Vol. XXXIV, Number 50 N September 13, 2013 Moonlight Run & Walk SPECIAL SECTION page 20 www.PaloAltoOnline.com A look at upcoming exhibits and performances page 34 Transitions 17 Spectrum 18 Eating 29 Shop Talk 30 Movies 31 Puzzles 74 NNews Council takes aim at solo drivers Page 3 NHome Perfectly passionate for pickling Page 40 NSports Stanford receiving corps is in good hands Page 78 2.5% Broker Fee on Duet Homes!* Live DREAM BIG! Big Home. Big Lifestyle. Big Value. Monroe Place offers Stunning New Homes in an established Palo Alto Neighborhood. 4 Bedroom Duet & Single Family Homes in Palo Alto Starting at $1,538,888 410 Cole Court <eZllb\lFhgkh^IeZ\^'\hf (at El Camino Real & Monroe Drive) Palo Alto, CA 94306 100&,,+&)01, Copyright ©2013 Classic Communities. In an effort to constantly improve our homes, Classic Communities reserves the right to change floor plans, specifications, prices and other information without prior notice or obliga- tion. Special wall and window treatments, custom-designed walks and patio treatments and other items featured in and around the model homes are decorator-selected and not included in the purchase price. Maps are artist’s conceptions and not to scale. Floor plans not to scale. All square footages are approximate. *The single family homes are a detached, single-family style but the ownership interest is condominium. Broker # 01197434. Open House | Sat. & Sun. | 1:30 – 4:30 27950 Roble Alto Drive, Los Altos Hills $4,250,000 Beds 5 | Baths 5.5 | Offices 2 | Garage 3 Car | Palo Alto Schools Home ~ 4,565 sq. -

Hoover Digest

HOOVER DIGEST RESEARCH + OPINION ON PUBLIC POLICY WINTER 2019 NO. 1 THE HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace was established at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, a member of Stanford’s pioneer graduating class of 1895 and the thirty-first president of the United States. Created as a library and repository of documents, the Institution approaches its centennial with a dual identity: an active public policy research center and an internationally recognized library and archives. The Institution’s overarching goals are to: » Understand the causes and consequences of economic, political, and social change » Analyze the effects of government actions and public policies » Use reasoned argument and intellectual rigor to generate ideas that nurture the formation of public policy and benefit society Herbert Hoover’s 1959 statement to the Board of Trustees of Stanford University continues to guide and define the Institution’s mission in the twenty-first century: This Institution supports the Constitution of the United States, its Bill of Rights, and its method of representative government. Both our social and economic sys- tems are based on private enterprise, from which springs initiative and ingenuity. Ours is a system where the Federal Government should undertake no govern- mental, social, or economic action, except where local government, or the people, cannot undertake it for themselves. The overall mission of this Institution is, from its records, to recall the voice of experience against the making of war, and by the study of these records and their publication to recall man’s endeavors to make and preserve peace, and to sustain for America the safeguards of the American way of life. -

Escuela Politécnica Nacional

ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA NACIONAL FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA DE SISTEMAS Propuesta para la Creación del Centro de Investigación Desarrollo e Innovación I+D+I de Tecnologías de la Información de la Escuela Politécnica Nacional TESIS PREVIA A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL GRADO DE MÁSTER (MSc) EN GESTIÓN DE LAS COMUNICACIONES Y TECNOLOGÍA DE LA INFORMACIÓN ING. MERA GUEVARA OMAR FRANCISCO [email protected] ING. PAREDES LUCERO EDGAR SANTIAGO [email protected] DIRECTOR: ING. MONTENEGRO ARMAS CARLOS ESTALESMIT [email protected] Quito, Diciembre 2014 I DECLARACIÓN Nosotros, Omar Francisco Mera Guevara, Edgar Santiago Paredes Lucero, declaramos bajo juramento que el trabajo aquí descrito es de nuestra autoría; que no ha sido previamente presentada para ningún grado o calificación profesional; y, que hemos consultado las referencias bibliográficas que se incluyen en este documento. A través de la presente declaración cedemos nuestros derechos de propiedad intelectual correspondientes a este trabajo, a la Escuela Politécnica Nacional, según lo establecido por la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual, por su Reglamento y por la normatividad institucional vigente. Omar Francisco Mera Edgar Santiago Paredes Guevara Lucero II CERTIFICACIÓN Certifico que el presente trabajo fue desarrollado por Omar Francisco Mera Guevara y Edgar Santiago Paredes Lucero, bajo mi supervisión. Ing. Carlos Montenegro DIRECTOR DE PROYECTO III AGRADECIMIENTOS Con profunda gratitud a mis padres Pancho y Lidi, a mis hijos Dereck y Nayve, a mi esposa Jenny, a mis hermanos Edison y Elizabeth, a mis incondicionales amigos Edgar, Mr Julio Vera; por el apoyo incondicional, confianza, paciencia y dedicación que supieron brindarme durante todo el tiempo que hemos estado juntos, por toda la impronta humana que han dejado para mi vida. -

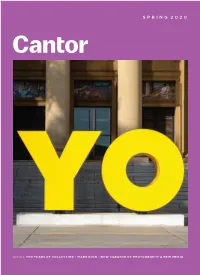

Spring 2020 Magazine

SPRING 2020 INSIDE TEN YEARS OF COLLECTING • MARK DION • NEW CURATOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY & NEW MEDIA “This brightly colored, monumental piece has something to say—and not just because it’s a play on words. One thing we hope it conveys to students and visitors n is a good-natured ‘Come in! You a m r e k c a are welcome here.’ ” D an Sus Susan Dackerman John & Jill Freidenrich Director of the Cantor Arts Center Yo, Cantor! The museum’s newest large-scale sculpture, in Japanese. “The fact that this particular work Deborah Kass’s OY/YO, speaks in multicultural resonates so beautifully in so many languages to tongues: Oy, as in “oy vey,” is a Yiddish term so many communities is why I wanted to make it of fatigue, resignation, or woe. Yo is a greeting monumental,” artist Kass told the New York Times. associated with American teenagers; it also means “I” in Spanish and is used for emphasis Learn more at museum.stanford.edu/oyyo CONTENTS SPRING 2020 QUICK TOUR 4 News, Acquisitions & Museum Highlights FACULTY PERSPECTIVE 6 Sara Houghteling on Literature and Art CURATORIAL PERSPECTIVE 7 Crossing the Caspian with Alexandria Brown-Hejazi FEATURE 8 Paper Chase: Ten Years of Collecting 3 THINGS TO KNOW 13 About Artist and Alumnus Richard Diebenkorn EXHIBITION GRAPHIC 14 A Cabinet of Cantor Curiosities: PAGE 8 Paper Chase: the Cantor’s major spring exhibition Mark Dion Transforms Two Galleries includes prints from Pakistani-born artist Ambreen Butt, whose work contemplates issues of power and autonomy in the lives of young women. -

The University at a Glance About the University Stanford University

About the University Stanford University n October 1, 1891, the 465 new students who were on Ohand for opening day ceremonies at Leland Stanford Junior University greeted Leland and Jane Stanford enthusi- astically, with a chant they had made up and rehearsed only that morning. Wah-hoo! Wah-hoo! L-S-J-U! Stanford! Its wild and spirited tone symbolized the excitement of this bold adventure. As a pioneer faculty member recalled, “Hope was in every heart, and the presiding spirit of freedom prompted us to dare greatly.” For the Stanford’s on that day, the university was the real- ization of a dream and a fitting tribute to the memory of their only son, who had died of typhoid fever weeks before his sixteenth birthday. Far from the nation’s center of culture and unencumbered by tradition or ivy, the new university Millions of volumes are housed in many libraries throughout the campus. drew students from all over the country: many from California; some who followed professors hired from other colleges and universities; and some simply seeking adventure in the West. Though there were many difficulties during the first months – housing was inadequate, microscopes and books were late in arriving from the East – the first year fore- told greatness. As Jane Stanford wrote in the summer of Stanford University 1892, “Even our fondest hopes have been realized.” The University at a Glance About the University Stanford University Ideas of “Practical Education” Stanford People Governor and Mrs. Stanford had come from families of By any measure, Stanford’s faculty – which numbers modest means and had built their way up through a life of approximately 1,700 – is one of the most distinguished in hard work. -

Our Founders Envisioned It, Our Students Aspire to It, and Our World Demands It

2019 #ChoosePublicService, p. 7 New Emerson Fellowship Equips Students as Social Justice Leaders, p. 2 What End-of-Life Care Taught Me About Medicine Beyond Medication, p. 3 Our founders envisioned it, our students aspire to it, and our world demands it. National Advisory Board From the Directors Jamie Halper, ’81; P ’15, ’17, ’20, ’21; Chair Ekpedeme “Pamay ” M. Bassey, ’93; Vice Chair Jacques Antebi, ’86; P ’15 Henry J. Brandon, III, ’78; P ’17, ’19 Stanford University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne and Provost Persis Drell have announced Ronald Brown, ’94 a bold vision to guide Stanford’s future as a purposeful university that applies innovative Vaughn Derrick Bryant, ’94 teaching and learning to benefit humanity. Throughout campus, faculty, staff, and students Lara Burenin, ’06, MA ’07 Milton Chen, MA ’83, PhD ’86, P ’09 collaborate with local, national, and global partners to address to complex social and Matthew Colford, ’14, JD ’22, MBA ’22 environmental challenges. A core component of these efforts is Cardinal Service—a bold, Bret Comolli, MBA ’89; P ’17, ’21 Courtney Cooperman, ’20 university-wide initiative that elevates service as an essential feature of a Stanford education. Janet Diaz, ’19 Katie Hanna Dickson, ’84 Toward realizing the vision for Stanford, the Haas Center is now a part of the Office of the Senior Susan Ford Dorsey, P ’16 Vice Provost for Education, Harry Elam, Jr. This office plays a critical strategic role in advancing Molly Efrusy, ’94 Stanford’s educational aims, and the new organizational structure enables the Haas Center to Sally Falkenhagen, ’75, P ’16 Molly Brown Forstall, ’91, JD ’94, P ’21 continue coordinating, synthesizing, and innovating with partners campus-wide to build and Mimi Haas strengthen academic connections and a networked approach to public service.