The World According to Sophie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The White Rose Program

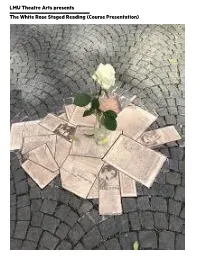

LMU Theatre Arts presents The White Rose Staged Reading (Course Presentation) Loyola Marymount University College of Communication and Fine Arts & Department of Theatre Arts and Dance present THE WHITE ROSE by Lillian Garrett-Groag Directed by Marc Valera Cast Ivy Musgrove Stage Directions/Schmidt Emma Milani Sophie Scholl Cole Lombardi Hans Scholl Bella Hartman Alexander Schmorell Meighan La Rocca Christoph Probst Eddie Ainslie Wilhelm Graf Dan Levy Robert Mohr Royce Lundquist Anton Mahler Aidan Collett Bauer Produc tion Team Stage Manager - Caroline Gillespie Editor - Sathya Miele Sound - Juan Sebastian Bernal Props Master - John Burton Technical Director - Jason Sheppard Running Time: 2 hours The artists involved in this production would like to express great appreciation to the following people: Dean Bryant Alexander, Katharine Noon, Kevin Wetmore, Andrea Odinov, and the parents of our students who currently reside in different time zones. Acknowledging the novel challenges of the Covid era, we would like to recognize the extraordinary efforts of our production team: Jason Sheppard, Sathya Miele, Juan Sebastian Bernal, John Burton, and Caroline Gillespie. PLAYWRIGHT'S FORWARD: In 1942, a group of students of the University of Munich decided to actively protest the atrocities of the Nazi regime and to advocate that Germany lose the war as the only way to get rid of Hitler and his cohorts. They asked for resistance and sabotage of the war effort, among other things. They published their thoughts in five separate anonymous leaflets which they titled, 'The White Rose,' and which were distributed throughout Germany and Austria during the Summer of 1942 and Winter of 1943. -

SMALL CRIMES DIAS News from PLANET MARS ALL of a SUDDEN

2016 IN CannES NEW ANNOUNCEMENTS UPCOMING ALSO AVAILABLE CONTACT IN CANNES NEW Slack BAY SMALL CRIMES CALL ME BY YOUR NAME NEWS FROM NEW OFFICE by Bruno Dumont by E.L. Katz by Luca Guadagnino planet mars th Official Selection – In Competition In Pre Production In Pre Production by Dominik Moll 84 RUE D’ANTIBES, 4 FLOOR 06400 CANNES - FRANCE THE SALESMAN DIAS NEW MR. STEIN GOES ONLINE ALL OF A SUDDEN EMILIE GEORGES (May 10th - 22nd) by Asghar Farhadi by Jonathan English by Stephane Robelin by Asli Özge Official Selection – In Competition In Pre Production In Pre Production [email protected] / +33 6 62 08 83 43 TANJA MEISSNER (May 11th - 22nd) GIRL ASLEEP THE MIDWIFE [email protected] / +33 6 22 92 48 31 by Martin Provost by Rosemary Myers AN ArtsCOPE FILM NICHolas Kaiser (May 10th - 22nd) In Production [email protected] / +33 6 43 44 48 99 BERLIN SYNDROME MatHIEU DelaUNAY (May 10th - 22nd) by Cate Shortland [email protected] / + 33 6 87 88 45 26 In Post Production Sata CissokHO (May 10th - 22nd) [email protected] / +33 6 17 70 35 82 THE DARKNESS design: www.clade.fr / Graphic non contractual Credits by Daniel Castro Zimbrón Naima ABED (May 12th - 20th) OFFICE IN PARIS MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL In Post Production [email protected] / +44 7731 611 461 9 Cité Paradis – 75010 Paris – France Tel: +33 1 53 34 90 20 | Fax: +33 1 42 47 11 24 [email protected] [email protected] Proudly sponsored by www.memento-films.com | Follow us on Facebook NEW OFFICE IN CANNES 84 RUE D’ANTIBES, 4th FLOOR -

Uk Films for Sale in Cannes 2009

UK FILMS FOR SALE IN CANNES 2009 Supported by Produced by 1234 TMoviehouse Entertainment Cast: Ian Bonar, Lyndsey Marshal, Kieran Bew, Mathew Baynton Gary Phillips Genre: Drama Rés. Du Grand Hotel 47 La Croisette, 6Th Director: Giles Borg Floor Producer Simon Kearney Tel: +33 4 93 38 65 93 Status : Completed [email protected] Home Office Tel: +44 20 7836 5536 Synopsis Ardent musician Stevie (guitar, vocals) endures a day-job he despises and can't find a girlfriend but... at least he has his music! With friend Neil (drums) he's been kicking around for a while not achieving much but when the pair of misfits team-up with the more-experienced Billy (guitar) and his cute pal Emily (bass) the possibility they might be on to something really good presents itself. For Stevie this is the opportunity he's been waiting for with the band and just maybe... Emily too! 13 Hrs TEyeline Entertainment Cast: Isabella Calthorpe, Gemma Atkinson, Tom Felton, Joshua Duncan Napier-Bell Bowman Lerins Stand R10 Genre: Horror Tel: +33 4 92 99 33 02 Director: Jonathan Glendening [email protected] Writer: Adam Phillips Home Office Tel: +44 20 8144 2994 Producer Nick Napier-Bell, Romain Schroeder, Tom Reeve Status : Post-Production Synopsis A full moon hangs in the night sky and lightning streaks across dark storm clouds. Sarah Tyler returns to her troubled family home in the isolated countryside, for a much put-off visit. As the storm rages on, Sarah, her family and friends shore up for the night, cut off from the outside world. -

Cinema B Paradiso

CI NEMA B PARADISO 03B12 Programmkino St. Pölten 1. Programmkino in NÖ, 02742-21 400, www.cinema-paradiso.at B EDITORIAL Frauenpower im Cinema Paradiso. Rund um den Internationalen Frauentag (8. März) erobern starke Frauen die Leinwand und die Bühne. Allen voran Meryl Streep mit einer preiswürdigen Darbietung als Die Eiserne Lady. Obwohl Streep selbst die Politik der ehemaligen britischen Premierministerin Margaret Thatchers ablehnt, verleiht sie ihrer Figur eine ungekannte Menschlichkeit. Streeps englische Kolleginnen Judi Dench und Maggie Smith reisen ins ferne Indien, um dort in ein sehr spezielles Seniorenheim zu ziehen. Davon erzählt die feine Komödie Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. Ihr Spielfilmdebüt gibt die preisgekrönte Österreichische Dokumentarfilmerin Anja Salomonowitz: Zur NÖ-Premiere von Spanien kommen die Haupt- darstellerInnen Tatjana Alexander und Cornelius Obonya ins Kino. In der französischen Best- sellerverfilmung Sarahs Schlüssel entdeckt Kristin Scott Thomas nach und nach die Ge- schichte eines jüdischen Mädchens. Als Eröffnungsfilm des Frauenschwerpunkts zeigen wir Tagaus, tagein, das Porträt einer eigensinnigen Bäuerin, mit anschließender Diskussion. Passion, eine filmische Hommage an die Philosophin Christiane Singer wird von der Regis- seurin Carolina Mair präsentiert. Die weiteren Filmneustarts: Shame, das Porträt eines Sexbesessenen mit einem grandiosen Michael Fassbender und Carey Mulligan. Atemberaubendes Kino aus Lateinamerika ist Und dann der Regen mit Gael García Bernal. Der Vorarlberger Hans Weingartner (Die fetten Jahre sind vorbei) erzählt in Die Summe meiner einzelnen Teile beeindruckend von der Freundschaft eines Aussteigers und eines Buben am Rand unserer Leistungsgesellschaft. Der Atmende Gott ist eine filmische Reise zu den Ursprüngen des Yoga. Starke Frauen auf der Bühne. Drei Autorinnen lesen aus ihren Krimis: Clementine Skorpil, Edith Kneifl und Jacqueline Gillespie. -

Février 2018 Luxembourg City Film Festival Terry Gilliam John

02 Luxembourg City Film Festival Terry Gilliam John Cassavetes Ciné-conférence « Film & Politik » Février 2018 Informations pratiques 3 Sommaire Tableau synoptique 4 Cinéma 17, place du Théâtre Abonnement gratuit L-2613 Luxembourg au programme mensuel Luxembourg City Film Festival 6 Tél. : 4796 2644 Université Populaire du Cinéma 10 Tickets online [email protected] Ciné-conférence « Film & Politik » 12 sur www.cinematheque.lu www.luxembourg-ticket.lu Journée mondiale contre l’excision 14 Le Monde en doc 16 Soirée spéciale « Ciné-débat » 18 Kino mat Häerz 20 Bd. Royal R. Willy Goergen Essential Cinema 22 R. des Bains Côte d’Eich Rétrospective Terry Gilliam 26 R. Beaumont Rétrospective John Cassavetes 34 Weekends@Cinémathèque 40 Cinema Paradiso 48 Baeckerei R. du Fossé R. Aldringen R. L’affiche du mois 55 R. des Capucins des R. Av. de la Porte-Neuve la de Av. Grand-Rue Bd. Royal Bd. Salle de la Cinémathèque Accès par bus : Glossaire P Parking Place du Théâtre Lignes 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 19, 20 vo version originale non sous-titrée vostf version originale sous-titrée en français Arrêt : Badanstalt (rue des Bains) vostang version originale sous-titrée en anglais Place d’Arme R. du Curé vostf+all version originale sous-titrée Caisse Vente des billets ½ heure Administration / en français et en allemand vf version française avant les séances Archives / Bibliothèque vl version luxembourgeoise 10, rue Eugène Ruppert La Cinémathèque de la Ville de Luxembourg est un € musée du cinéma ayant pour mission la préservation vofr version originale française Plein Tarif Billet : 3,70 vall version allemande L-2453 Luxembourg et valorisation du patrimoine cinématographique inter- Carnet 10 billets : 25,00 € vostall version originale sous-titrée en allemand R. -

Canberra International Film Festival 27 October – 6 November

CIFF_05_DL*new 5/10/05 5:07 PM Page 1 th The 9 Canberra International Film Festival 27 October – 6 November 2005 Program Electric Shadows City Walk Canberra City www.canberrafilmfestival.com.au CIFF_05_DL*new 5/10/05 5:07 PM Page 2 Welcome th The 9 Canberra International Film Festival It is with genuine enthusiasm that I welcome you to the 9th Canberra International Film Festival. After nine years the Festival has become a Canberra landmark, and the city’s premiere cinema event. The Canberra International Film Festival has always looked to the future. And as we look forward to the tenth festival in 2006 it is exciting to know that next year the festival will hopefully be presented in the new Dendy Films/Electric Shadows Cinema complex in Bunda Street. The film and television landscape in Canberra has undergone considerable change in the past ten years, and it is pleasing to know that the Festival has been a significant partner in propelling that change. Along with our sister festival, the Canberra Short Film Festival, we have helped raise the profile of quality cinema and filmmaking. We have dared our local filmmakers to dream. A short while ago, local filmmaker Duane Fogwell had a sell out season here at Electric Shadows for his short film, The Milkman. Such an event would have been unheard of ten years ago. But we believe that it is a sign of things to come. This year’s festival is our biggest so far with 24 films from 16 countries, 11 of which are Australian Premieres. -

Hommage an Audrey Hepburn Zum 80

INSTITUT FILM MUSEUM 5 2009 Hommage an Audrey Hepburn Zum 80. Geburtstag AUSSTELLUNGEN H.R. Giger. Kunst · Design · Film | Bernhard Grzimek KINO Klassiker & Raritäten | Werkschau Amos Gitai | Franz Schömbs Was tut sich – im deutschen Film? | Oberhausen on Tour | Cinelatino Barbara Klemm | Dokumentarfilm & Gespräch| Cinéfête 9 | Kinderkino Schätze aus den Archiven MUSEUMSPÄDAGOGIK | BIBLIOTHEK 2 INHALT 3 Editorial 20 Klassiker & Raritäten IMPRESSUM 4 H.R. GIGER. Kunst · Design · Film 24 Oberhausen on Tour Kurzfilm- Programmheft Mai 2009 Sonderausstellung und Katalog programme vom 12. bis 17. Mai Deutsches Filminstitut / Deutsches Filmmuseum 6 Bernhard Grzimek – zum 100. Geburtstag 25 Cinelatino Herausgeber: Deutsches Filminstitut – DIF e.V. Galerieausstellung Festivalprogramm des lateiname- Schaumainkai 41, 60596 Frankfurt am Main Direktorin: Claudia Dillmann (V.i.S.d.P.) ri kanischen Films vom 1. bis 7. Mai 7 Ausstellungen on Tour Stellvertretender Direktor: Hans-Peter Reichmann Redaktion: Horst Martin, Lisa Dressler (Mitarbeit) 28 Bridges and Disengagements 8 Was tut sich – im deutschen Film? Lektorat und Schlussredaktion: Katja Thorwarth Werkschau Amos Gitai bis Juni Matthias Emcke präsentiert Mitarbeit: Beate Dannhorn, Daniela Dietrich, PHANTOMSCHMERZ (D 2007-09) am 29. Mai 30 Dokumentarfilm & Gespräch Monika Haas, Sabrina Jähner, David Kleingers, Tina Klotz, Peter Kropp, Christine Moser, Susanne MENSCHEN TRÄ U ME TATEN (2007) am 19. Mai 9 Nahaufnahme: Julia Jentsch Neubronner, Jessica Niebel, Simon Ofenloch, Nadja Rademacher, Ulrike Stiefelmayer, Katja Thorwarth, 10 Hommage an Audrey Hepburn 30 Samstagsfilme Gary Vanisian, Thomas Worschech zum 80. Geburtstag Neue Reihe ab 30. Mai mit Anja Czioska Grafik: conceptdesign, Offenbach Filmreihe vom 2. bis 30. Mai 31 Barbara Klemm Druck: Central-Druck Trost GmbH & Co. KG, Heusenstamm 14 Filmkultur für Schulen im ganzen Land Preview mit Gästen am 13. -

Wettbewerb (48

Filme im Wettbewerb 24 Wochen (24 Weeks) von Anne Zohra Berrached mit Julia Jentsch, Bjarne Mädel, Johanna Gastdorf, Emilia Pieske, Maria Dragus. Produktion: zero one film, Berlin; ZDF/Das kleine Fernsehspiel, Mainz; Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg, Ludwigsburg. Weltvertrieb: Beta Cinema, Oberhaching. Originalsprache: Deutsch. Untertitel: Englisch Alone in Berlin (Jeder stirbt für sich allein) von Vincent Perez mit Emma Thompson, Brendan Gleeson, Daniel Brühl, Mikael Persbrandt, Monique Chaumette, Joachim Bissmeier, Katrin Pollitt, Lars Rudolph, Uwe Preuss, Daniel Sträßer. Produktion: X Filme Creative Pool, Berlin; Master Movies, Paris; FilmWave, London; Pathé Production, Paris; Buffalo Films, Paris; WS Film Produktion, Dirmstein. Deutscher Verleih: X Verleih, Berlin. Weltvertrieb: Cornerstone Films, London. Originalsprache: Englisch. Untertitel: Deutsch L'avenir (Things to Come) von Mia Hansen-Løve mit Isabelle Huppert, André Marcon, Roman Kolinka, Edith Scob, Sarah Le Picard, Solal Forte, Elise Lhomeau, Lionel Dray, Grégoire Montana-Haroche, Lina Benzerti. Produktion: CG Cinema, Paris; DETAiLFILM, Hamburg. Deutscher Verleih: Zentropa Hamburg, Hamburg. Weltvertrieb: Les Films du Losange, Paris. Originalsprache: Französisch. Untertitel: Deutsch/Englisch Boris sans Béatrice (Boris without Béatrice) von Denis Côté mit James Hyndman, Simone- Élise Girard, Denis Lavant, Isolda Dychauk, Dounia Sichov, Laetitia Isambert-Denis, Bruce La Bruce, Louise Laprade. Produktion: Metafilms, Montreal. Weltvertrieb: Films Boutique, Berlin. Originalsprache: -

Hörfilme in Der SBS Filme Mit Audiodeskription

Hörfilme in der SBS Filme mit Audiodeskription Gesamtkatalog, Stand 1.1.2021 2 Herausgeber: SBS Schweizerische Bibliothek für Blinde, Seh- und Lesebehinderte Grubenstrasse 12 CH-8045 Zürich Fon +41 43 333 32 32 Fax +41 43 333 32 33 www.sbs.ch [email protected] © SBS Schweizerische Bibliothek für Blinde, Seh- und Lesebehinderte 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Spielfilme ............................................................................................... 5 Mundartfilme ....................................................................................... 184 Dokumentarfilme ................................................................................. 195 Spielfilme 5 Spielfilme 1. Mai - Helden bei der Arbeit. Regie: Ludwig & Glasen u.a. Schauspieler: Jacob Matschenz, Ludwig Trepte. Deutschland, 2008. Ein elfjähriger Türke, zwei Jugendliche aus der Kleinstadt und ein gehörnter Provinzpolizist: sie alle verschlägt es am 1. Mai nach Kreuzberg - wo wie jedes Jahr die Emotionen hoch kochen. Der kleine Yavuz hungert nach Anerkennung. Er will auf der Demo "einen Bullen platt machen", um seinen grossen Bruder zu beeindrucken. Doch durch die unverhoffte Begegnung mit dem Alt-68er Harry, entwickelt sich sein Tag völlig anders als geplant. Die Jungs Jacob und Pelle aus Minden erhoffen sich das grosse Abenteuer in der Hauptstadt. Sie sind neugierige Krawalltouristen - scheinbar ziellos driftend zwischen Touri- Programm, dem besten Dönerladen Berlins und dem Demonstrationszug des schwarzen Blocks. Polizist Uwe wiederum hat ganz andere Sorgen, -

FACE to FACE with GERMAN FILMS 2020 Campaign

In 2016, the national information and advisory center for the promotion of German films worldwide - German Film Service + Marketing - launched a unique campaign promoting German cinema achievements through exceptional German talent to the film industry and wider international cinema-going community. A B O U T The initiative – FACE TO FACE WITH GERMAN FILMS – shines a spotlight on the most influential individuals currently working in the German film industry and who represent just some of the many dynamic ‘faces’ of F A C E German filmmaking today. T O F A C E The 2016 launch of the FACE TO FACE WITH GERMAN FILMS campaign presented six actresses as these ‘faces’, at the London Film Festival and W I T H through the year, across a series of press events, a photographic advertising campaign and through the international launches of their diverse film and television projects. The actresses were PAULA BEER, LIV G E R M A N LISA FRIES, SANDRA HÜLLER, JULIA JENTSCH, SASKIA ROSENDAHL and LILITH STANGENBERG. F I L M S At the 2017 Cannes International Film Festival, the FACE TO FACE WITH GERMAN FILMS initiative entered the second phase of the campaign with the support of some of Germany’s most eclectic actors: VOLKER BRUCH, ALEXANDER FEHLING, LOUIS HOFMANN, JANNIS NIEWÖHNER, TOM SCHILLING and RONALD ZEHRFELD. 2018 saw the continuation of the FACE TO FACE WITH GERMAN FILMS campaign, this time celebrating the visionaries behind the camera, by showcasing prominent directors in the German film industry, who have already garnered a great deal of international recognition for their varied works: EMILY ATEF, VALESKA GRISEBACH, LARS KRAUME, ANCA MIRUNA LAZARESCU, BURHAN QURBANI and DAVID WNENDT. -

Films, Séries Et Sites Pouvant Enrichir Des Germanistes Curieux a Regarder

Films, séries et sites pouvant enrichir des germanistes curieux A regarder en VO sous titrés (ou en français), pour s’entraîner à la compréhension de l’oral et/ou enrichir sa culture générale Voici un code couleur concernant les axes thématiques : Mythes et héros/ Mythen und Helden (MH) Espaces et échanges/ Raum und Austausch(EE) Lieux et formes de pouvoir/ Orte und Formen der Macht (LFP) L’idée de progrès/ Idee des Fortschritts (IP) 1. Thema Deutschland heute « Im Juli/ Julie en juillet »2000 von Fatih Akin ( mit Moritz Bleibtreu, Christiane Paul) EE Romantischer Roadmovie von Deutschland in die Türkei « Lola rennt / Cours, Lola cours » 1998 (mit Moritz Bleibtreu , Franka Potente) Thriller : Und wenn alles anders kommt ? Eine Geschichte mit verschiedenen Endversionen « die fetten Jahre sind vorbei / The Edukators» 2004 (mit Daniel Brühl, Julia Jentsch) EE LFP MH Engagiertes Drama :Wie weit kann ich für meine Überzeugung gehen ? 3 Jugendliche kämpfen gegen den Kapitalismus und können nicht mehr zurück « Jenseits der Stille/ Au-delà du silence » 1996 (mit Sylvie Testud) EE LFP Drama :Die hörende Tochter taubstummer Eltern entdeckt die Musik und konfrontiert sich mit ihrem Vater. « Almanya/ Almanya, bienvenue en Allemagne » 2011 EE Komödie über eine türkische Gastarbeiterfamilie, ihre Integration über 3 Generationen und die witzige Konfrontation von 2 Kulturen. « Fack ju Göthe/ Un prof pas comme les autres » 2013 (mit Katia Riemann, Elyas M'Barek) Komödie : Ein kleiner Einblick in das deutsche Schulsystem « die Welle/ La vague »2008 (mit Jürgen Vogel, Elyas M'Barek, Christiane Paul) MH LFP Drama : Ist eine Diktatur heute in Deutschland noch möglich ? Ein Lehrer macht ein Experiment mit seiner Klasse… 2. -

Babylonberlin.De September

AM ANFANG WAR DIE LÜGE IN MEMORIAM CLAUDE LANZMANN Die Lüge im Film über die SHOAH ist essentiell, weil die Wahrheit die menschliche Vor- stellungskraft übersteigt! Es kann nicht dargestellt werden. EIN LEBENDER GEHT VORBEI F 1997, R: Claude Lanzmann, 65 Min, OmU 24.9. 17:45 Auch am Anfang der SHOAH steht die Lüge. Wie hätte man denn Millionen Menschen sagen können, dass man gedenkt, sie alle umzubringen? Die Verbreitung dieses Gedan- DER KARSKI-BERICHT F 2010, 49 Min, Englisch (OmU) 24.9. 17:45 kens hätte zu riesigen Verwerfungen geführt. Die soziale Ordnung wäre schlicht zu- sammengebrochen. So, wie es mit einer Verzögerung von 12 Jahren dann auch passiert ist. Es braucht Zeit, bis sich ein Gedanke materialisiert. In der Zwischenzeit hatten die DER LETZTE DER UNGERECHTEN [Le Dernier des Injustes] Lager ihre grausige Arbeit geleistet, war es für viele Menschen zu spät. Zum Schluss F/AT 2013, R: Claude Lanzmann, 216 Min, OmU 25.9. 20:00 | 30.9. 13:30 fi el das Unvorstellbare auf die Auslöser zurück. Allerdings – natürlich – nicht mit der gleichen Härte. Weil das schlicht unmenschlich wäre! Bemerkenswert, dass sich einige SHOAH F 1985, R: Claude Lanzmann, 540 Min, OmU nachher über die Unannehmlichkeiten in Deutschland beschweren. „Auch wir haben 23.9. 14:00 | 29.9. 13:30 gelitten.“ „Davon haben wir nichts gewusst!“. Und noch schlimmer: Manche haben so einen Gefallen daran gefunden, dass sie die im System immanente Lüge fortschreiben SOBIBOR, 14. OKTOBER 1943, 16 UHR möchten. „Die Toten sind gar nicht ermordet worden!“ Dies ist nichts anderes, als wür- F 2001, R: Claude Lanzmann, 95 Min, OmU 16.9.