Be True to the Earth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soul on Fire: the Life and Music of Peter Steele Copyright © 2014 FYI Press, Inc

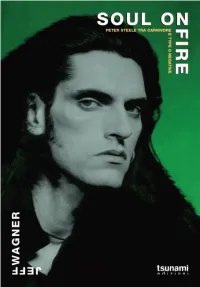

SOUL ON THE LIFE AND MUSIC OF FIRE PETER STEELE WAGNER BY JEFF BY Dedicated to the memory of Peter Thomas Ratajczyk and Barbara Emma Banyai SOF Sample 4/11/2015 - Copyright FYI Press, Inc. NOT FOR SALE OR TO BE COPIED. Soul on Fire: The Life and Music of Peter Steele Copyright © 2014 FYI Press, Inc. All rights reserved. www.petersteelebio.com Cover photo by John Wadsworth Cover design by Scott Hoffman and Adriene Greenup Photographs as credited Book design by Scott Hoffman for Eyedolatry Design Copyediting by Valerie Brooks Editing and additional contributions by Adriene Greenup First published in the United States in 2014 by FYI PRESS Greensboro, NC 27403 www.fyipress.com ISBN 978-1-934859-45-2 Printed in the United States of America SOF Sample 4/11/2015 - Copyright FYI Press, Inc. NOT FOR SALE OR TO BE COPIED. “There is no weapon more powerful than the human soul on fire” —General Ferdinand Foch “Do you believe in forever? I don’t even believe in tomorrow” —Peter Steele SOF Sample 4/11/2015 - Copyright FYI Press, Inc. NOT FOR SALE OR TO BE COPIED. SOF Sample 4/11/2015 - Copyright FYI Press, Inc. NOT FOR SALE OR TO BE COPIED. CONTENTS Prologue: Too Late for Apologies vii Part I: RED 1 Ground Zero Brooklyn 1 2 Into the Reactor 13 3 You Are What You Eat 35 4 Extreme Neurosis 63 Part II: GREEN 5 Power Tools 91 6 Into the Sphincter of the Beast 117 (and other Fecal Origins) 7 Religion…Women…Fire 129 8 An Accidental God 147 9 Product of Vinnland 171 Part III: BLACK 10 It’s Coming Down 203 11 The Death of the Party 225 12 Repair — Maintain — Improve 249 13 All Hail and Farewell 275 Gratitude 296 Endnotes 297 SOF Sample 4/11/2015 - Copyright FYI Press, Inc. -

Notes Towards an Autobiography Patrick White-- Writing, Politics And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert Coolabah, No.9, 2012, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians, Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Notes Towards an Autobiography 1 Patrick White-- Writing, Politics and the Australia-Fiji Experience Satendra Nandan Copyright © Satendra Nandan 2012 This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged FOR BRUCE BENNETT, friend and fellow traveller I’m grateful to the NLA, so full of wonders and treasures, for generously awarding me this fellowship. For the last three months, I’ve been able to read and research, write and reflect, and meet a variety of scholars, staff and friends, with the feeling that how one’s life intersects with so many other lives: that, I think, is one’s real autobiography . Happy Valley , Patrick White’s first published novel in 1939, has that as a theme and its epigraph is from Mahatma Gandhi. But more on these men later. In March this year Jyoti and I returned from Fiji after six eventful years. We’d gone there in February 2006, from the ANU and the University of Canberra, to help establish the first University of Fiji. Of course, there was USP, established in 1968, which I joined as one of the first local lecturers in 1969 and resigned to take up a ministry in the Bavadra cabinet in 1987: I resigned on Monday; the Colonel staged his coup on Thursday. -

Arry Music from the 40’S to All of Today’S Hits ! John E Martell Wedding Mobile Disc Jockeys 460 E

We carry music from the 40’s to all of today’s hits ! John E Martell Wedding Mobile Disc Jockeys 460 E. Lincoln Hwy. Specialists 215-752-7990 Langhorne Pa 19047 1/1/2017 SOME OF THE MUSIC AVAILABLE ( OUR MUSIC LIBRARY CONSISTS OF OVER 70,000 TITLES ) your name : ______________________ date of affair : ________________ location of affair : ___________________ [ popular dance ] ELECTRIC SLIDE - Marcia Griffiths CHA CHA SLIDE - DJ DON'T STOP BELIEVING - Journey OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL - Bob Seger WE ARE FAMILY - Sister Sledge DA BUTT - E U SO MANY MEN - Miguel Brown THIS IS HOW WE PARTY - S.O.A.P DO YOU WANNA FUNK - Sylvester FUNKYTOWN - Lipps Inc FEELS LIKE I'M IN LOVE - Kelly Marie THE BIRD - The Time IT'S RAINING MEN - Weather Girls SUPERFREAK-Rick James YOU DROPPED A BOMB-Gap Band BELIEVE - Cher ZOOT ZOOT RIOT-Cherry Poppin' Daddies IT TAKES TWO- Rob Base LOVE SHACK- B-52's EVERYBODY EVERYBODY-Black Box MIAMI- Will Smith HOT HOT HOT- Buster Poindexter HOLIDAY-Madonna JOCK JAMS- Various Artists IT WASN'T ME - Shaggy MACARENA- Los Del Rios RHYTHM IS A DANCER- Snap WHOOP THERE IT IS- Tag Team DO YOU REALLY WANT ME- Robyn GONNA MAKE YOU SWEAT- C&C Music TWLIGHT ZONE - 2 Unlimited PUMP UP THE JAM - Technotronics NEW ELECTRIC SLIDE - Grand Master Slice RAPPER'S DELIGHT - Sugar Hill Gang MOVE THIS - Technotronics HEARTBREAKER - Mariah Carey HIT MAN - A B Logic I'M GONNA GET YOU - Bizarre Inc SUPERMODEL - Ru Paul APACHE - Sugar Hill Gang CRAZY IN LOVE - Beyonce' DA DA DA - Trio GET READY FOR THIS - 2 Unlimited THE BOMB - Bucketheads STRIKE IT UP -

Www .Tsunamiedizioni.Com Campione Gra Tuito

CAMPIONE GRATUITO - WWW.TSUNAMIEDIZIONI.COM CAMPIONE GRATUITO “Non c’è arma più potente dell’animo umano in fiamme”. Generale Ferdinand Foch “Se credo nell’eternità? Io non credo neppure nel domani”. Peter Steele CAMPIONE GRATUITO - WWW.TSUNAMIEDIZIONI.COM CAMPIONE GRATUITO CAMPIONE GRATUITO - WWW.TSUNAMIEDIZIONI.COM CAMPIONE GRATUITO SOUL ON Web Tsunami Facebook Titolo originale dell’opera: “Soul on Fire: The Life and Music of Peter Steele” Copyright © 2014 FYI Press, Inc. Edizione originale pubblicata in USA da: FYI Press, Greensboro, NC 27403 Copyright © 2015 A.SE.FI. Editoriale Srl - Via dell’Aprica, 8 - Milano www.tsunamiedizioni.com - twitter: @tsunamiedizioni Prima edizione Tsunami Edizioni, settembre 2015 - I Cicloni 23 Tsunami Edizioni è un marchio registrato di A.SE.FI. Editoriale Srl Traduzione di Alessia Di Giovanni Foto di copertina di John Wadsworth, design di Scott Hoffman e Adriene Greenup Stampato nel mese di settembre 2015 da GESP - Città di Castello (PG) ISBN: 978-88-96131-78-7 Tutti i diritti riservati. È vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale, in qualsiasi formato senza l’autorizzazione scritta dell’Editore. Nell’impossibilità di risalire agli aventi diritto delle fotografie pubblicate, l’Editore si dichiara disponibile a sanare ogni eventuale controversia. - WWW.TSUNAMIEDIZIONI.COM CAMPIONE GRATUITO CAMPIONE GRATUITO - WWW.TSUNAMIEDIZIONI.COM CAMPIONE GRATUITO FIRE E TYPE O NEGATIVE PETER STEELE TRA CARNIVORE SOUL ON TRADUZIONE DI ALESSIA DI GIOVANNI JEFF CAMPIONE GRATUITO - WWW.TSUNAMIEDIZIONI.COM CAMPIONE GRATUITO WAGNER CAMPIONE GRATUITO - WWW.TSUNAMIEDIZIONI.COM CAMPIONE GRATUITO Dedicato alla memoria di Peter Thomas Ratajczyk e Barbara Emma Banyai CAMPIONE GRATUITO - WWW.TSUNAMIEDIZIONI.COM CAMPIONE GRATUITO INDICE CAMPIONE GRATUITO - WWW.TSUNAMIEDIZIONI.COM CAMPIONE GRATUITO PROLOGO: TROPPO TARDI PER SCUSARSI 9 PARTE I - ROSSO 1 GROUND ZERO: BROOKLYN 15 2 NEL REATTORE 27 3 SEI QUELLO CHE MANGI 49 4 NEVROSI ESTREMA 79 PARTE II - VERDE 5 STRUMENTI DI POTERE 107 6 NELLO SFINTERE DELLA BESTIA 133 7 RELIGIONE.. -

The Role of Translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature : a Case Study of Howard Goldblatt's Translations of Mo Yan's Works

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Translation 3-9-2016 The role of translation in the Nobel Prize in literature : a case study of Howard Goldblatt's translations of Mo Yan's works Yau Wun YIM Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Yim, Y. W. (2016). The role of translation in the Nobel Prize in literature: A case study of Howard Goldblatt's translations of Mo Yan's works (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd/16/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Translation at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. THE ROLE OF TRANSLATION IN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE: A CASE STUDY OF HOWARD GOLDBLATT’S TRANSLATIONS OF MO YAN’S WORKS YIM YAU WUN MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 THE ROLE OF TRANSLATION IN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE: A CASE STUDY OF HOWARD GOLDBLATT’S TRANSLATIONS OF MO YAN’S WORKS by YIM Yau Wun 嚴柔媛 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Translation LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 ABSTRACT The Role of Translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature: A Case Study of Howard Goldblatt’s Translations of Mo Yan’s Works by YIM Yau Wun Master of Philosophy The purpose of this thesis is to explore the role of the translator and translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature through an illustration of the case of Howard Goldblatt’s translations of Mo Yan’s works. -

Leto As Mother: Representations of Leto with Apollo and Artemis in Attic Vase Painting of the Fifth Century B.C

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Lavinia Foukara Leto as Mother: Representations of Leto with Apollo and Artemis in Attic Vase Painting of the Fifth Century B.C. aus / from Archäologischer Anzeiger Ausgabe / Issue Seite / Page 63–83 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa/2027/6626 • urn:nbn:de:0048-journals.aa-2017-1-p63-83-v6626.5 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion der Zentrale | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition 2510-4713 ISSN der gedruckten Ausgabe / ISSN of the printed edition Verlag / Publisher Ernst Wasmuth Verlag GmbH & Co. Tübingen ©2019 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Mit dem Herunterladen erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) von iDAI.publications an. Die Nutzung der Inhalte ist ausschließlich privaten Nutzerinnen / Nutzern für den eigenen wissenschaftlichen und sonstigen privaten Gebrauch gestattet. Sämtliche Texte, Bilder und sonstige Inhalte in diesem Dokument unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts gemäß dem Urheberrechtsgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Inhalte können von Ihnen nur dann genutzt und vervielfältigt werden, wenn Ihnen dies im Einzelfall durch den Rechteinhaber oder die Schrankenregelungen des Urheberrechts gestattet ist. Jede Art der Nutzung zu gewerblichen Zwecken ist untersagt. Zu den Möglichkeiten einer Lizensierung von Nutzungsrechten wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an die verantwortlichen Herausgeberinnen/Herausgeber der entsprechenden Publikationsorgane oder an die Online-Redaktion des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts ([email protected]). -

Notes on Contributors 7 6 7

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS 7 6 7 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS ALLEN, Walter. Novelist and Literary Critic. Author of six novels (the most recent being All in a Lifetime, 1959); several critical works, including Arnold Bennett, 1948; Reading a Novel, 1949 (revised, 1956); Joyce Cary, 1953 (revised, 1971); The English Novel, 1954; Six Great Novelists, 1955; The Novel Today, 1955 (revised, 1966); George Eliot, 1964; and The Modern Novel in Britain and the United States, 1964; and of travel books, social history, and books for children. Editor of Writers on Writing, 1948, and of The Roaring Queen by Wyndham Lewis, 1973. Has taught at several universities in Britain, the United States, and Canada, and been an editor of the New Statesman. Essays: Richard Hughes; Ring Lardner; Dorothy Richardson; H. G. Wells. ANDERSON, David D. Professor of American Thought and Language, Michigan State University, East Lansing; Editor of University College Quarterly and Midamerica. Author of Louis Bromfield, 1964; Critical Studies in American Literature, 1964; Sherwood Anderson, 1967; Anderson's "Winesburg, Ohio," 1967; Brand Whitlock, 1968; Abraham Lincoln, 1970; Robert Ingersoll, 1972; Woodrow Wilson, 1975. Editor or Co-Editor of The Black Experience, 1969; The Literary Works of Lincoln, 1970; The Dark and Tangled Path, 1971 ; Sunshine and Smoke, 1971. Essay: Louis Bromfield. ANGLE, James. Assistant Professor of English, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti. Author of verse and fiction in periodicals, and of an article on Edward Lewis Wallant in Kansas Quarterly, Fall 1975. Essay: Edward Lewis Wallant. ASHLEY, Leonard R.N. Professor of English, Brooklyn College, City University of New York. Author of Colley Cibber, 1965; 19th-Century British Drama, 1967; Authorship and Evidence: A Study of Attribution and the Renaissance Drama, 1968; History of the Short Story, 1968; George Peele: The Man and His Work, 1970. -

Download Scans

12e JAARGANG 1e KWARTAAL 1947 PHILOSOPHIA R·EFORMATA ORGA,AN VAN DE VEREENIGING VOOR CALVI NISTISCHE W!JSBEGEERTE ONDER REDACTIEVA~J DR J. BOHATEC DR J. H. DIEMER DR H. DO 0 YEW EERD DR H. G. STOKER DR C. VAN TIL DR D. H. TH. VOLLENHOVEN UITGAVE J.H. KOK N.V KAMPEN HOOFOREDACTEUR: Prof. Dr H. DOOYE"\VEERD, Or anje Nassaulaan 13, Al\iSTERDAl\I-ZUID REDACTIELEDEN: Dr J. BOf-IATEC, \VEENEN Dr J. H. DIEMER, GnO?\IXGE:\ Dr H. G. STOKER, POTCIIEFSTTIOO:\1 Dr C. V.A..l~ TIL, PHILADELPHIA - Dr D. H. TIl. 'VOLLENIIO\'EN, Al\ISTETIDAI\1 Secretariaat: Dr .1. P. A. Mekkes, Waalsdorperweg 245, 's Gravenhage INHOUDSOPGAVE pag. OXTWERP ENER AESTHETICA OP GROXDSLAG DER \VIJSBEGEERTE DER \VETSIDEE, II, door H. R. ROOK.l\lAAKER 1 OPVOEDI:"JG, ONDER\VIJS, SCI-lOOLVERBAKD, I, door DR K J. POPMA. .......... 36 CALYIXISME EN VOLKEKRECHT, door DR J R. STEL- LINGA •............ .. 42 ONTWERP ENER AESTHETICA OP GRONDSLAG DER WIJSBEGEERTE DER WETSIDEE DOOR H. R. ROOKMAAKER. § 10. Stijl en schoonheid aan niet-aesthetisch gequalificeerde structuren. Schoonheid aan natuurdingen is een stijlloze schoonheid 53), immers, deze schoonheid is gefundeerd in de leidende functie van het (in één van de natuurzijden gequalificeerde) ding en dus niet in de (historische) beheersende vorming. Aan alle structureel in de historische functie ge- fundeerde objectieve dingstructuren kunnen we echter stijl herkennen; het ding is immers tot stand gekomen in een menselijke vormingsarbeid.. Stijl is dus geen „privilege" voor kunstwerken, voor aesthetisch-gequa- lificeerde dingen. Zo merken we schoonheid, stijl op aan sociaal-ge- qualificeerde structuren als stoelen, glaswerk, wasbakken etc. -

Literature and Freedom Occasional Papers

Literature and Freedom Mario Vargas Liosa In this CIS Occasional Paper, Mario Vargas Liosa highlights the mutually beneficial relationship between literature and freedom. Where freedom does not exist, censorship and self-censorship stifle creativity - literature tends to become conformist and Literature and Freedom predictable. Colonial Latin America produced scarcely a writer still worth reading in three hundred years, while in Elizabethan England disdain for dramatists saw them left in peace, allowing Shakespeare's genius to flourish. In repressive societies, though, the book is the medium best suitedto keeping freedom alive. Audio visual technology is expensive and easily controlled by those in power. Books, by contrast, can be written, reproduced and circulated by underground cultures. While praising good cinema and television, Vargas Llosa emphasises the book's unique contribution to culture and freedom. Mario Vargas Liosa Mario Vargas Liosa, born in 1936, is one of the most acclaimed Latin American writers. His books include Conversation in the Cathedral(1 969), AuntJulia and the Scrzptwriter (1977), and In Praise of the Stepmother (1988). His autobiography will be published in English translation in 1994 under the title Like a Fish in Water. In 1993 he gave the CIS's tenthJohn Bonython Lecture, entitled Questions of Conquest and Culture (0P47). In 1990 he ran unsuccessfully for the Presidency of Peru. He recently ac- quired dual citizenship of Spain and Peru, and now lives in Europe. occasional papers ISBN 0 949769 95 9 ISSN 0155 7386 CIS Occasional Papers 48 Published February 1994 by Foreword The Centre for Independent Studies Limited Mario Vargas Liosa "- The Writer and the Word All rights reserved. -

Why the Hell Am I Doing This?

The Origin of the Toilet Paper: How Soul on Fire Came To Be In January of 2013, I spent an hour on the phone with Darcie Rowan, Peter’s niece. The most memorable portion of this call was her words telling me, "Peter was clean and sober when he died, and he didn't die of a heart attack. We want your book to set the record straight." To say my heart quickened was an understatement. What had happened to Peter Steele? Darcie and I confirmed my trip to NY and NJ to meet with Peter Steele’s surviving sisters on Feb.9th. It was to be a day full of questions, laughter, tears and some great Italian food! While I was to be in the area, I would also meet with Monte Conner and Mark Abramson of Roadrunner Records. It is exciting and bittersweet all at once. At this point, I was merely dipping my toe into the Green Man’s life but I could already sense a presence of sorts. Maybe it was just imaginary, or maybe this is what happens when you become someone’s biographer. For the next 2 years, I would be eating, sleeping and drinking green and black. Back in NY and NJ everyone is gathering together their memorabilia and best memories of Peter. Back in NC I am busy organizing the book in my head, and preparing interview questions. Why the hell am I doing this? First, because I have been a fan of Peter’s special, singular creative vision since that great first Carnivore album was released in 1986. -

Artemis Und Der Weg Der Frauen Von Der Geburt Bis Zur Mutterschaft Am Beispiel Von Kulten Auf Der Peloponnes

ARTEMIS UND DER WEG DER FRAUEN VON DER GEBURT BIS ZUR MUTTERSCHAFT AM BEISPIEL VON KULTEN AUF DER PELOPONNES INAUGURAL-DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER DOKTORWÜRDE DER PHILOSOPHISCHEN FAKULTÄT I DER JULIUS-MAXIMILIANS-UNIVERSITÄT WÜRZBURG VORGELEGT VON MARIA GENNIMATA AUS THESSALONIKI (WÜRZBURG 2006) ERSTGUTACHTER: PROFESSOR DR. U. SINN ZWEITGUTACHTER: PROFESSORIN DR. R. LINDNER (†) TAG DES KOLLOQUIUMS: 18.07.2006 INHALT Vorwort ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Abkürzungsverzeichnis ........................................................................................................... 11 Einleitung – Forschungsstand ................................................................................................. 17 Methodischer Ansatz............................................................................................................... 33 I. BEISTAND DER ARTEMIS VON DER GEBURT BIS ZUR MUTTERSCHAFT: FUNKTIONS- EPIKLESEN JENSEITS DER PELOPONNES 1. GEBURT UND WOCHENBETT 1.1. Chitone, Kithone................................................................................................. 45 1.1.1. Literarische und epigraphische Belege ................................................... 45 1.1.2. Die rituelle Praxis der Kleiderweihe ....................................................... 47 1.2. Dynatera ............................................................................................................. 48 1.3. Eileithyia............................................................................................................ -

Inspiration and Τέχνη: Divination in Plato's

AARON LANDRY | 85 Inspiration INTRODUCTION and Τέχνη: In Plato’s Ion, inspiration functions in con- Divination in tradistinction to technē.1 Since Ion’s rhapso- dic expertise does not stand up to Socrates’ Plato’s Ion epistemological critique, his performances of Homer cannot stem from knowledge, but from elsewhere, from divine inspiration. The two are presented as a strict disjunction. Yet in both cases there is an appeal to divination. If rhapsody, and poetry by extension, cannot synthesize the two, why does Socrates seem 2 Aaron Landry to think that divination can? This puzzle has Humber College caused quite a bit of consternation about the 3 [email protected] value and subject matter of the dialogue. In particular, it is unclear what Socrates thinks about the nature of poetic and rhapsodic ins- piration. In this essay, I will argue that divi- nation constitutes an alternate, and improved, framework for Ion to model his expertise on. By clarifying the role and scope of divination in the Ion, I aim to show that Socrates’ disjunctive account – inspiration or technē – can actually be integrated. In so doing, I argue that there are in fact positive philosophical theses latent ABSTRACT in the dialogue. In part I, I rehearse the contrasting accoun- In Plato’s Ion, inspiration functions in ts of divination in the dialogue. In the first argumentative exchange, divination is refe- contradistinction to technē. Yet, paradoxically, in both cases, there is an appeal to divination. renced as a paradigmatic technē. The seer is I interrogate this in order to show how these best equipped to speak about the contrasting two disparate accounts can be accommodat- depictions of divination given by Homer and ed.