National Identity Sara Cousins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Team Australia?': Understanding Acculturation from Multiple

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Post 2013 2018 ‘Team Australia?’: Understanding acculturation from multiple perspectives Justine Dandy Edith Cowan University Tehereh Zianian Carolyn Moylan Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013 Part of the Migration Studies Commons Dandy, J., Ziaian, T., & Moylan, C. (2018). ‘Team Australia?’: Understanding acculturation from multiple perspectives. In M. Karasawa, M. Yuki, K. Ishii, Y. Uchida, K. Sato, & W. Friedlmeier (Eds.), Venture into cross-cultural psychology: Proceedings from the 23rd Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology.Available here This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013/4985 Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Papers from the International Association for Cross- IACCP Cultural Psychology Conferences 2018 ‘Team Australia?’: Understanding Acculturation From Multiple Perspectives Justine Dandy School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Tahereh Ziaian School of Psychology, University of South Australia Carolyn Moylan Independent non-affiliated, Western Australia Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers Part of the Psychology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Dandy, J., Ziaian, T., & Moylan, C. (2018). ‘Team Australia?’: Understanding acculturation from multiple perspectives. In M. Karasawa, M. Yuki, K. Ishii, Y. Uchida, K. Sato, & W. Friedlmeier (Eds.), Venture into cross-cultural psychology: Proceedings from the 23rd Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/152/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IACCP at ScholarWorks@GVSU. -

The Politics of Affluence

The politics of affluence The Institute’s recent paper on ‘the rise of the middle-class battler’ (Discussion Paper No. 49) appears to have struck a powerful chord in the community. Clive Hamilton, the report’s author, comments on the political implications of ‘imagined hardship’. No. 33 December 2002 A recent Newspoll survey, statement that they cannot afford to buy commissioned by the Institute, reveals everything they really need. that 62 per cent of Australians believe that they cannot afford to buy The politics of affluence everything they really need. When we The proportion of ‘suf- Clive Hamilton consider that Australia is one of the fering rich’ in Australia is world’s richest countries, and that even higher than in the Who should pay for mater- Australians today have incomes three USA, widely regarded as nity leave? times higher than in 1950, it is the nation most obsessed remarkable that such a high proportion Natasha Stott Despoja with money. feel their incomes are inadequate. The Coalition’s Claytons health policy It is even more remarkable that almost Richard Denniss half (46 per cent) of the richest In other words, a fifth of the poorest households in Australia (with incomes households say that they do not have Letter to a farmer over $70,000 a year) say they cannot afford difficulties affording everything they Clive Hamilton to buy everything they really need. The really need, suggesting that they have proportion of ‘suffering rich’ in some money left over for ‘luxuries’. This Deep cuts in greenhouse Australia is even higher than in the USA, is consistent with anecdotal evidence that gases widely regarded as the nation most some older people living entirely on the Clive Hamilton obsessed with money. -

Teaching About Australia. ERIC Digest

ED319651 1990-02-00 Teaching about Australia. ERIC Digest. ERIC Development Team www.eric.ed.gov Table of Contents If you're viewing this document online, you can click any of the topics below to link directly to that section. Teaching about Australia. ERIC Digest. 1 WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO TEACH ABOUT AUSTRALIA'? 2 WHERE DOES AUSTRALIAN STUDIES BELONG IN THE CURRICULUM'? WHAT STRATEGIES MIGHT BE USED IN CLASSROOMS TO TEACH ABOUT REFERENCES AND ERIC RESOURCES 5 ERIC t,Oil Digests ERIC Identifier: ED319651 Publication Date: 1990-02-00 Author: Prior, Warren R. Source: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education Bloomington IN. Teaching about Australia. ERIC Digest. THIS DIGEST WAS CREATED BY ERIC, THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER. FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT ERIC, CONTACT ACCESS ERIC 1-800-LET-ERIC It is only in very recent times that Australia has penetrated the consciousness of many American classroom teachers as a potentially worthwhile area of study for their students. Most teachers have little or no formal education about Australia. Recent Australian-American sporting events, films, and tourist advertising have been widely ED319651 1990-02-00 Teaching about Australia. ERIC Digest. Page 1 of 7 www.eric.ed.gov ERIC Custom Transformations Team publicized in the United States. But mostly these have presented stereotypical images of Australia. The few school textbooks that mention Australia tend to reinforce these stereotypes. The explanation of this lack of interest perhaps reflects as much on Australians themselves, who tend to be so obsessed with inventing national images that outside observers just don't know where to begin a study about Australia. -

Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes

NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES X X I NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are respectfully advised that this book includes the names and images of people who are now deceased. Cover: Detail from Caroline Chisholm's portrait by Angelo Collen Hayter, oil on canvas, 1852, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG 459). Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes © Reserve Bank of Australia 2016 E-book ISBN 978-0-6480470-0-1 Compiled by: John Murphy Designed by: Rachel Williams Edited by: Russell Thomson and Katherine Fitzpatrick For enquiries, contact the Reserve Bank of Australia Museum, 65 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000 <museum.rba.gov.au> CONTENTS Introduction VI Portraits from the present series Portraits from pre-decimal of banknotes banknotes Banjo Paterson (1993: $10) 1 Matthew Flinders (1954: 10 shillings) 45 Dame Mary Gilmore (1993: $10) 3 Charles Sturt (1953: £1) 47 Mary Reibey (1994: $20) 5 Hamilton Hume (1953: £1) 49 The Reverend John Flynn (1994: $20) 7 Sir John Franklin (1954: £5) 51 David Unaipon (1995: $50) 9 Arthur Phillip (1954: £10) 53 Edith Cowan (1995: $50) 11 James Cook (1923: £1) 55 Dame Nellie Melba (1996: $100) 13 Sir John Monash (1996: $100) 15 Portraits of monarchs on Australian banknotes Portraits from the centenary Queen Elizabeth II of Federation banknote (2016: $5; 1992: $5; 1966: $1; 1953: £1) 57 Sir Henry Parkes (2001: $5) 17 King George VI Catherine Helen -

'Out of Sight, out of Mind? Australia's Diaspora As A

Out of sight, out of mind? Australia’s diaspora as a pathway to innovation March 2018 Contents Collaborating with our diaspora .........................................................................................................3 Australian businesses’ ‘collaboration deficit’ .......................................................................................4 The diaspora as an accelerator for collaboration .................................................................................7 Understanding the Australian diaspora’s connection to Australia ......................................................14 What now? .......................................................................................................................................27 References ........................................................................................................................................30 This report has been prepared jointly with Advance. Advance is the leading network of global Australians and alumni worldwide. The many millions of Australians who have, do, or will live outside of the country represent an incredible, unique and largely untapped national resource. Its mission is to engage, connect and empower leading global Australians and Alumni; to reinvest new skills, talents and opportunities into Australia; to move the country forward. diaspora di·as·po·ra noun A diaspora is a scattered population whose origin lies within a smaller geographic locale. Diaspora can also refer to the movement of the population from -

Indigenous Australian Art in Intercultural Contact Zones

Coolabah, Vol.3, 2009, ISSN 1988-5946 Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians, Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Indigenous Australian art in intercultural contact zones Eleonore Wildburger Copyright ©2009 Eleanore Wildburger. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged Abstract: This article comments on Indigenous Australian art from an intercultural perspective. The painting Bush Tomato Dreaming (1998), by the Anmatyerre artist Lucy Ngwarai Kunoth serves as model case for my argument that art expresses existential social knowledge. In consequence, I will argue that social theory and art theory together provide tools for intercultural understanding and competence. Keywords: Indigenous Australian art and social theory. Introduction Indigenous Australian artworks sell well on national and international art markets. Artists like Emily Kngwarreye, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Kathleen Petyarre are renowned representatives of what has become an exquisite art movement with international appreciation. Indigenous art is currently the strongest sector of Australia's art industry, with around 6,000 artists producing art and craft works with an estimated value of more than A$300 million a year. (Senate Committee, 2007: 9-10) At a major Indigenous art auction held in Melbourne in 2000, Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula's famous painting Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa was sold for a record price of A$ 486,500. Three years before, it was auctioned for A$ 206,000. What did Johnny W. Tjupurrula receive? – just A$ 150 when he sold that painting in 1972. (The Courier Mail, 29 July 2000) The Süddeutsche Zeitung (06 September 2005) reports that Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri received A$ 100 for his painting Emu Corroboree Man in 1972. -

International Undergraduate UQ Guide 2022 Create Your Future the UNIVERSITY of QUEENSLAND INTERNATIONAL UNDERGRADUATE UQ GUIDE 2022

International Undergraduate UQ Guide 2022 Create your future THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND INTERNATIONAL UNDERGRADUATE UNDERGRADUATE INTERNATIONAL UQ UQ GUIDE 2022 Study enquiries Online enquiries future-students.uq.edu.au/contact-us/ international-online-enquiries Outside Australia +61 7 3067 8608 Within Australia (freecall) 1800 671 980 General office Level 2, JD Story Building The University of Queensland St Lucia Qld 4072 AUSTRALIA +61 7 3365 7941 CRICOS Provider 00025B facebook.com/uniofqld twitter.com/uq_news instagram.com/uniofqld weibo.com/myuq 昆士兰大学教育资讯 Important dates 2022 Contents JANUARY 1 January New Year’s Day 3 January New Year’s Day public holiday 26 January Australia Day holiday Welcome to UQ 1 29 January Summer Semester ends** FEBRUARY 14–18 February Orientation Week Our global reputation 2 21 February Semester 1 starts Pioneering change 4 MARCH 31 March Census date (Semester 1) APRIL 15 April Good Friday Transforming your learning 6 18 April Easter Monday 18–22 April Mid-semester break Industry relevant 8 Find 25 April ANZAC Day holiday A truly global network 10 26 April Semester 1 resumes out more MAY 2 May Labour Day holiday Game-changing graduates 12 31 May Semester 2 application closing date* The perfect place to study 14 30 May–3 June Revision period Meet us in your location JUNE 4–18 June Examination period UQ St Lucia 16 18 June Semester 1 ends UQ academic and administrative staff 18 June–25 July Mid-year break UQ Gatton 18 often travel internationally, giving you JULY 11–15 July July graduations** the opportunity to meet one of our team 18–22 July Mid-year Orientation Week UQ Herston 19 25 July Semester 2 starts members at an event local to you. -

Indigenous Australians and Land in New South Wales

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Indigenous Australians and Land in New South Wales by Talina Drabsch Briefing Paper No 9/04 RELATED PUBLICATIONS • Aborigines, Land and National Parks in New South Wales by Stewart Smith, Briefing Paper No 2/97 • The Native Title Debate: Background and Current Issues by Gareth Griffith, Briefing Paper No 15/98 • Indigenous Issues in NSW by Talina Drabsch, Background Paper No 2/04 ISSN 1325-4456 ISBN 0 7313 1764 5 July 2004 © 2004 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Indigenous Australians and Land in New South Wales by Talina Drabsch NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE David Clune (MA, PhD, Dip Lib), Manager..............................................(02) 9230 2484 Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government / Law .........................(02) 9230 2356 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ......................(02) 9230 2768 Rowena Johns (BA (Hons), LLB), Research Officer, Law........................(02) 9230 2003 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Research Officer, Law ...................................(02) 9230 3085 Stewart Smith (BSc (Hons), MELGL), Research -

THE HARVEST of a QUIET EYE.Pdf

li1 c ) 1;: \l} i e\ \. \ .\ The University of Sydney Copyright in relation to this thesis* Unde r the Copyright Act 1968 (several provision of which are referred to below), this thesis must be used only under the normal conditions of scholarly fair dealing for the purposes of research, criticism or review. In particular no results or conclusions should be extracted (rom it, nor should it be copied or closely paraphrased in whole or in part without the written consent of the author. Proper written acknowledgement should be made for any assistance obtained from this thesis. Under Section 35(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 'the .uthor of a literary, dramatic. musical or artistic work is the owner of any copyright subsisting in the work', By virtUe of Section 32( I) copyright 'subsists in an original literary, dramatic. musical or artistic work that is unpublished' and of which the author was an Australian citizen, an Australian protected person or a person resident in Australia. The Act. by Section 36( I) provides: 'Subject to this Act. the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who. not being the owner of the copyright and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia, or authorises the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright'. Section 31 (I )(.)(i) provides thot copyright includes the exclusive right to'reproduce the work. in a material form'.Thus, copyright is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, reproduces or authorises the reproduction of a work., or of more than a reasonable part of the work, in a material form, unless the reproduction is a 'fair dealing' with the work 'for the purpose of research or swdy' as further defined in Sections 40 and . -

The Impact of Immigration on the Ageing of Australia's Population

The Impact of Immigration on the Ageing of Australia’s Population Peter McDonald and Rebecca Kippen May 1999 Professor Peter McDonald is Head of the Demography Program in the Research School of Social Sciences of the Australian National University. Rebecca Kippen is a Research Assistant in the Demography Program at the Australian National University. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 1999 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without permission from the Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs. Table of Contents A statement of the issue ........................................................................................................ 3 Why is our population ageing?.............................................................................................. 3 Research and opinion on the issue: 1983-1998 ...................................................................... 4 Against the flow? Alvarado and Creedy ................................................................................ 6 The issue reborn: 1999.......................................................................................................... 7 A revisionist view: Glenn Withers and ‘A Younger Australia’ .............................................. 8 The real questions ................................................................................................................10 A standard population projection..........................................................................................11 -

A Survey of Australia May 7Th 2005

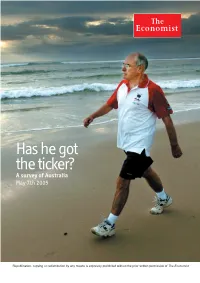

Has he got the ticker? A survey of Australia May 7th 2005 Republication, copying or redistribution by any means is expressly prohibited without the prior written permission of The Economist The Economist May 7th 2005 A survey of Australia 1 Has he got the ticker? Also in this section The limits to growth Australia’s constraints are all on the supply side. They need to be tackled. Page 3 Beyond lucky The economy has a lot more going for it than mineral resources. Page 5 Innite variety A beautiful empty country full of tourist attractions. Page 6 The reluctant deputy sheri Australia’s skilful foreign policy has made it many friends. Keeping them all happy will not be easy. Page 7 God under Howard The prime minister keeps on winning elec- tions because he understands how Australia has changed. Page 9 Australia’s economic performance has been the envy of western countries for well over a decade. But, says Christopher Lockwood, the Australians old and new country now needs a new wave of reform to keep going The country seems to be at ease with its new- HE best-loved character in Australian ment, but to win re-election on, policies est arrivals, but not yet with its rst Tfolklore is the battler, the indomi- that were as brutal as they were necessary. inhabitants. Page 11 table little guy who soldiers on despite all It was under this remarkable Labor team the odds, struggling to hold down his job, that the really tough things were done: the raise his family and pay o his mortgage. -

PRIMARY Education Resource

A break away! painted at Corowa, New South Wales, and Melbourne, 1891 oil on canvas 137.3 x 167.8 cm Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, Elder Bequest Fund, 1899 PRIMARY Education resource Primary Education Resource 1 For teachers How to use this learning resource for primary students Tom Roberts is a major INTRODUCTION exhibition of works from the National Gallery of Australia’s ‘All Australian paintings are in some way a homage to Tom Roberts.’ Arthur Boyd collection as well as private and Tom Roberts (1856–1931) is arguably one of Australia’s public collections from around best-known and most loved artists, standing high among his talented associates at a vital moment in local painting. Australia. His output was broad-ranging, and includes landscapes, figures in the landscape, industrial landscapes and This extraordinary exhibition brings together Roberts’ cityscapes. He was also Australia’s leading portrait most famous paintings loved by all Australians. Paintings painter of the late nineteenth and early twentieth such as Shearing the rams 1888–90 and A break away! centuries. In addition he made a small number of etchings 1891 are among the nation’s best-known works of art. and sculptures and in his later years he painted a few nudes and still lifes. This primary school resource for the Tom Roberts exhibition explores the themes of the 9 by 5 Impression Roberts was born in Dorchester, Dorset, in the south of exhibition, Australia and the landscape, Portraiture, England and spent his first 12 years there. However he Making a nation, and Working abroad.