Our Cup Runneth Over | 431

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Affluence

The politics of affluence The Institute’s recent paper on ‘the rise of the middle-class battler’ (Discussion Paper No. 49) appears to have struck a powerful chord in the community. Clive Hamilton, the report’s author, comments on the political implications of ‘imagined hardship’. No. 33 December 2002 A recent Newspoll survey, statement that they cannot afford to buy commissioned by the Institute, reveals everything they really need. that 62 per cent of Australians believe that they cannot afford to buy The politics of affluence everything they really need. When we The proportion of ‘suf- Clive Hamilton consider that Australia is one of the fering rich’ in Australia is world’s richest countries, and that even higher than in the Who should pay for mater- Australians today have incomes three USA, widely regarded as nity leave? times higher than in 1950, it is the nation most obsessed remarkable that such a high proportion Natasha Stott Despoja with money. feel their incomes are inadequate. The Coalition’s Claytons health policy It is even more remarkable that almost Richard Denniss half (46 per cent) of the richest In other words, a fifth of the poorest households in Australia (with incomes households say that they do not have Letter to a farmer over $70,000 a year) say they cannot afford difficulties affording everything they Clive Hamilton to buy everything they really need. The really need, suggesting that they have proportion of ‘suffering rich’ in some money left over for ‘luxuries’. This Deep cuts in greenhouse Australia is even higher than in the USA, is consistent with anecdotal evidence that gases widely regarded as the nation most some older people living entirely on the Clive Hamilton obsessed with money. -

Tatz MIC Castan Essay Dec 2011

Indigenous Human Rights and History: occasional papers Series Editors: Lynette Russell, Melissa Castan The editors welcome written submissions writing on issues of Indigenous human rights and history. Please send enquiries including an abstract to arts- [email protected]. ISBN 978-0-9872391-0-5 Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Indigenous Human Rights and History Vol 1(1). The essays in this series are fully refereed. Editorial committee: John Bradley, Melissa Castan, Stephen Gray, Zane Ma Rhea and Lynette Russell. Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Colin Tatz 1 CONTENTS Editor’s Acknowledgements …… 3 Editor’s introduction …… 4 The Context …… 11 Australia and the Genocide Convention …… 12 Perceptions of the Victims …… 18 Killing Members of the Group …… 22 Protection by Segregation …… 29 Forcible Child Removals — the Stolen Generations …… 36 The Politics of Amnesia — Denialism …… 44 The Politics of Apology — Admissions, Regrets and Law Suits …… 53 Eyewitness Accounts — the Killings …… 58 Eyewitness Accounts — the Child Removals …… 68 Moving On, Moving From …… 76 References …… 84 Appendix — Some Known Massacre Sites and Dates …… 100 2 Acknowledgements The Editors would like to thank Dr Stephen Gray, Associate Professor John Bradley and Dr Zane Ma Rhea for their feedback on earlier versions of this essay. Myles Russell-Cook created the design layout and desk-top publishing. Financial assistance was generously provided by the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law and the School of Journalism, Australian and Indigenous Studies. 3 Editor’s introduction This essay is the first in a new series of scholarly discussion papers published jointly by the Monash Indigenous Centre and the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

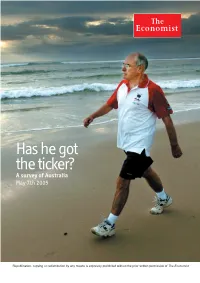

A Survey of Australia May 7Th 2005

Has he got the ticker? A survey of Australia May 7th 2005 Republication, copying or redistribution by any means is expressly prohibited without the prior written permission of The Economist The Economist May 7th 2005 A survey of Australia 1 Has he got the ticker? Also in this section The limits to growth Australia’s constraints are all on the supply side. They need to be tackled. Page 3 Beyond lucky The economy has a lot more going for it than mineral resources. Page 5 Innite variety A beautiful empty country full of tourist attractions. Page 6 The reluctant deputy sheri Australia’s skilful foreign policy has made it many friends. Keeping them all happy will not be easy. Page 7 God under Howard The prime minister keeps on winning elec- tions because he understands how Australia has changed. Page 9 Australia’s economic performance has been the envy of western countries for well over a decade. But, says Christopher Lockwood, the Australians old and new country now needs a new wave of reform to keep going The country seems to be at ease with its new- HE best-loved character in Australian ment, but to win re-election on, policies est arrivals, but not yet with its rst Tfolklore is the battler, the indomi- that were as brutal as they were necessary. inhabitants. Page 11 table little guy who soldiers on despite all It was under this remarkable Labor team the odds, struggling to hold down his job, that the really tough things were done: the raise his family and pay o his mortgage. -

Robert J. Dole

Robert J. Dole U.S. SENATOR FROM KANSAS TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES E PL UR UM IB N U U S HON. ROBERT J. DOLE ÷ 1961±1996 [1] [2] S. Doc. 104±19 Tributes Delivered in Congress Robert J. Dole United States Congressman 1961±1969 United States Senator 1969±1996 ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1996 [ iii ] Compiled under the direction of the Secretary of the Senate by the Office of Printing Services [ iv ] CONTENTS Page Biography .................................................................................................. ix Proceedings in the Senate: Prayer by the Senate Chaplain Dr. Lloyd John Ogilvie ................ 2 Tributes by Senators: Abraham, Spencer, of Michigan ................................................ 104 Ashcroft, John, of Missouri ....................................................... 28 Bond, Christopher S., of Missouri ............................................. 35 Bradley, Bill, of New Jersey ...................................................... 43 Byrd, Robert C., of West Virginia ............................................. 45 Campbell, Ben Nighthorse, of Colorado ................................... 14 Chafee, John H., of Rhode Island ............................................. 19 Coats, Dan, of Indiana ............................................................... 84 Cochran, Thad, of Mississippi ................................................... 3 Cohen, William S., of Maine ..................................................... 79 Coverdell, Paul, of Georgia ....................................................... -

Dislocating the Frontier Essaying the Mystique of the Outback

Dislocating the frontier Essaying the mystique of the outback Dislocating the frontier Essaying the mystique of the outback Edited by Deborah Bird Rose and Richard Davis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Dislocating the frontier : essaying the mystique of the outback. Includes index ISBN 1 920942 36 X ISBN 1 920942 37 8 (online) 1. Frontier and pioneer life - Australia. 2. Australia - Historiography. 3. Australia - History - Philosophy. I. Rose, Deborah Bird. II. Davis, Richard, 1965- . 994.0072 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Indexed by Barry Howarth. Cover design by Brendon McKinley with a photograph by Jeff Carter, ‘Dismounted, Saxby Roundup’, http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn3108448, National Library of Australia. Reproduced by kind permission of the photographer. This edition © 2005 ANU E Press Table of Contents I. Preface, Introduction and Historical Overview ......................................... 1 Preface: Deborah Bird Rose and Richard Davis .................................... iii 1. Introduction: transforming the frontier in contemporary Australia: Richard Davis .................................................................................... 7 2. -

Josephite Justice Office PO Box 1508 North Sydney NSW 2059

Josephite Justice Office PO Box 1508 North Sydney NSW 2059 SUBMISSION TO SELECT COMMITTEE Submission to the inquiry on Australia’s declarations made under certain international laws. Submitted by Josephite Justice Office Contact Jan Barnett rsj Submission to the inquiry on Australia’s declarations made under certain international laws. The Sisters of St Joseph is a religious congregation founded by Mary MacKillop. This submission comes from the Josephite Justice desk. We are grateful to the Senate for this opportunity to comment on this matter of high importance. The circumstances of Australia’s declarations made in 2002 concerning the jurisdiction of the ICJ or ITLOS are a source of disturbance for a growing number of Australians. We share this distress. Further information about these circumstances and about subsequent events impel us to call on the Senate to review the declarations and then to call on the parliament to reverse the declarations. The declarations removed Australia from the oversight of the two UN bodies which concern themselves with maritime boundary matters. It is now common knowledge that Australia used its withdrawal to engage in acts which severely disadvantaged Timor-Leste, in attempts to bring to Australian interests significant financial gain instead. The Timorese long-held preference for an internationally recognised border was unable to be pursued due to Australia’s highly advantageous position in not being under scrutiny as negotiations progressed. Furthermore, Australia sought to gain even greater benefits by spying on the Timorese during those negotiations. There are more untoward consequences of the decision to withdraw from the ICJ and ITLOS conventions. -

Productivity and Growth

Proceedings of a Conference PRODUCTIVITY AND GROWTH Economic Group Reserve Bank of Australia Proceedings of a Conference held at the H.C. Coombs Centre for Financial Studies, Kirribilli on 10/11 July 1995 PRODUCTIVITY AND GROWTH Editors: Palle Andersen Jacqueline Dwyer David Gruen Economic Group Reserve Bank of Australia The publication of these Conference papers is aimed at making the results of research done in the Bank, and elsewhere, available to a wider audience. The views expressed are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the Bank. References to the results and views presented should clearly attribute them to the authors, not to the Bank. The content of this publication shall not be reproduced, sold or distributed without the prior consent of the Reserve Bank of Australia. ISBN 0 642 23409 4 Printed in Australia by Ambassador Press Pty Ltd Table of Contents Introduction Jacqueline Dwyer 1 The Determinants of Long-Run Growth Steve Dowrick 7 Discussant: Bharat Trehan 48 Measuring Economic Progress Ian Castles 53 Discussant: John Quiggin 89 Labour-Productivity Growth and Relative Wages: 1978-1994 Philip Lowe 93 Discussant: David Mayes 135 Problems in the Measurement and Performance of Service-Sector Productivity in the United States Robert Gordon 139 Discussant: Stephen Poloz 167 Case Studies of the Productivity Effects of Microeconomic Reform Productivity Change in the Australian Steel Industry: BHP Steel 1982-1995 Peter Demura 172 The Performance of the NSW Electricity Supply Industry John Pierce, Danny Price and Deirdre -

Chapter Eleven Mabo and the Fabrication of Aboriginal History

Chapter Eleven Mabo and the Fabrication of Aboriginal History Keith Windschuttle Let me start by putting a case which, to The Samuel Griffith Society, might smack of heresy. There are two good arguments in favour of preserving the rights of the indigenous peoples who became subjects of the British Empire in the colonial era. The first is that, since 1066, British political culture has been committed to the “continuity theory” of constitutional law, in which the legal and political institutions of peoples who were vanquished, rendered vassals or subsumed by colonization were deemed to survive the process. Not even their conquest, John Locke wrote in his Second Treatise of Government, would have deprived them of their legal and political inheritance.1 So, after colonisation, indigenous peoples would have retained their laws and customs until they voluntarily surrendered them. The second argument is that the previous major decision in this field, by the Privy Council in 1889, was based on the assumption that, when New South Wales became a British colony in 1788, it was “a tract of territory practically unoccupied”. This is empirically untrue. At the time, there were probably about 300,000 people living on and subsisting off the Australian continent. Under any principle of natural justice, the Privy Council should have started by recognizing this. According to a forthcoming book on the history of Australian philosophy by James Franklin, provocatively entitled Corrupting the Youth, the Mabo decision derived primarily from the Catholic doctrine -

Sally Morgan: Aboriginal Identity Retrieved and Performed Within and Without My Place

Sally Morgan: Aboriginal Identity Retrieved and Performed within and without My Place Martin RENES Universidad de Barcelona [email protected] Recibido: 13/05/2010 Aceptado: 15/06/2010 ABSTRACT Sally Morgan’s auto/biography My Place (1987) played an important but contested role in recovering the indigenous heritage for Australia’s national self-definition when the country set out to celebrate the start of British colonisation with the Bicentennial (1988). My Place is strategically placed at a cultural and historical crossroads that has placated praise as well as criticism for its particular engagement with mainstream readership. indigenous and non-indigenous scholarship has pointed out how Morgan’s novel arguably works towards an assimilative conception of white reconciliation with an unacknowledged past of indigenous genocide, but two decades after its publication, the text’s ambiguous, hybrid nature may merit a more positive reading. A sophisticated merging of indigenous and non-indigenous genres of story-telling boosting a deceptive transparency, My Place inscribes Morgan’s aboriginality performatively as part of a long-standing, complex commitment to a re(dis)covered identity. On the final count, My Place’s engaged polyphony of indigenous voices traces a textual songline through the neglected and silenced history of the Stolen Generations, allowing a hybrid Aboriginal inscription of Sally Morgan’s identity inside and outside the text. Keywords: Australian Indigeneity, Aboriginal history, identity formation, reconciliation, performance Sally Morgan: la identidad Indígena recuperada y articulada dentro y fuera de Mi Lugar RESUMEN La auto/biografía Mi Lugar (1987) de la mestiza Sally Morgan jugó un papel importante aunque polémico en la recuperación de la herencia Indígena para la autodefinición nacional australiana cuando el país celebró el bicentenario (1988) del comienzo de la colonización británica. -

Drawing Inferences in the Proof of Native Title – Historiographic and Cultural Challenges and Recommendations for Judicial Guidance

DRAWING INFERENCES IN THE PROOF OF NATIVE TITLE – HISTORIOGRAPHIC AND CULTURAL CHALLENGES AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR JUDICIAL GUIDANCE SCOTT SINGLETON N2076357 BA, LLB (Qld), LLM (Hons) (QUT), Grad Dip Mil Law (Melb) Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Queensland Legal Practitioner of the High Court of Australia Submitted in fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR BILL DUNCAN ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR BILL DIXON SUPERVISOR: EXTERNAL PROFESSOR JONATHAN FULCHER (UQ) SUPERVISOR: Faculty of Law Queensland University of Technology 2018 KEYWORDS Evidence - expert witnesses - historiography - inferential reasoning - judicial guidance - law reform - native title - oral evidence - proof of custom 2 | P a g e ABSTRACT On 30 April 2015, the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) delivered its report Connection to Country: Review of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (ALRC Connection Report). The terms of reference for the inquiry leading up to the ALRC Connection Report included a request that the ALRC consider “what, if any, changes could be made to improve the operation of Commonwealth native title laws and legal frameworks,” including with particular regard to “connection requirements relating to the recognition and scope of native title rights and interests.” Amongst its recommendations, the ALRC Connection Report recommended guidance be included in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) regarding when inferences may be drawn in the proof of native title, including from contemporary evidence. To date, this recommendation has not been taken up or progressed by the Commonwealth Government. This thesis therefore develops such “Inference Guidelines” for the purposes of the proof of connection requirements in native title claims, in the form of a “Bench Book.” This thesis identifies various motivations for ensuring comprehensive, consistent and transparent guidelines for drawing inferences from historically-based sources of evidence. -

Working Families Are Aussie Battlers

Lost in the Struggle: Aussie Battlers in the Rhetoric of Opposition Joshua Bee Abstract This essay examines the role of the Aussie Battler in Australian political rhetoric. I argue that the Aussie Battler is a rhetorical incarnation of economic struggle, in which an Opposition utilises an ambiguity akin to dog whistling to foment and direct dissatisfaction towards an incumbent Government. Concepts like these are necessarily self-limiting after the Opposition deploying them is elected, as the circumstances from which they arise directly conflict with the expected rhetoric of competent and effective Government. Whilst particular incarnations of this rhetoric may hold partisan connotations, for instance Howard’s Battlers or Rudd’s Working Families, the pool of discontent they seek to foment and mobilise remains largely consistent. Curiously, this ongoing manipulation and promise of representation seems to undermine the essence of the Battler cultural ethic that makes identification with such articulations rhetorically significant. Introduction In 1988 John Howard, as Leader of the Opposition, gave a speech designed to foster a sense of disjuncture between the Government, and Australians who felt that - for a reason that perhaps was not entirely clear - life was harder than it should be.1 Over the next eight years, a shadowy horde of Aussie Battlers banded together against an elitist Government that was ‘out of touch’, and in 1996, ‘Howard’s Battlers’ were widely credited with delivering Australia its first Liberal Government in over a decade.2 Whilst their significance as a construct necessarily diminished during the Howard years, the pool of potentialities from which the Aussie Battler arose remained.