Nero, Apollo, and the Poets Author(S): Edward Champlin Source: Phoenix, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

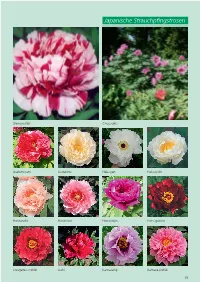

Japanische Strauchpfingstrosen

Japanische Strauchpfingstrosen Shimanishiki Chojuraku Asahiminato Godaishu Hakugan Hakuojishi Hanaasobi Hanakisoi Hanadaijin Hatsugarasu Jitsugetsu-nishiki Jushi Kamatafuji Kamata-nishiki 15 Kao Kokamon Kokuryu-nishiki Luo Yang Hong Meikoho Naniwa-nishiki Renkaku Rimpo Seidai Shim-daijin Shimano-fuji Shinfuso Shin-jitsugetsu Shinshifukujin Shiunden Taiyo Tamafuyo 16 Tamasudare Teni Yachiyotsubaki Yaezakura Yagumo Yatsukajishi Yoshinogawa High Noon Kinkaku Kinko Hakugan Kao 17 Europäische Strauchpfingstrosen Blanche de His Duchesse de Morny Isabelle Riviere Reine Elisabeth Chateau de Courson Jeanne d‘Arc Jacqueline Farvacques Zenobia 18 Rockii-Hybriden Souvenir de Lothar Parlasca Jin Jao Lou Ambrose Congrève Dojean E Lou Si Ezra Pound Fen He Guang Mang Si She Hai Tian E Hei Feng Die Hong Lian Hui He Ice Storm Katrin 19 Lan He Lydia Foote Rockii Ebert Schiewe Shu Sheng Peng Mo Souvenir de Ingo Schiewe Xue Hai Bing Xin Ye Guang Bei Zie Di Jin Feng deutscher Rockii-Sämling Lutea-, Delavayi- und Potaninii-Hybriden Anna Marie Terpsichore 20 Age of Gold Alhambra Alice in Wonderland Amber Moon Angelet Antigone Aphrodite Apricot Arcadia Argonaut Argosy Ariadne Artemis Banquet Black Douglas Black Panther Black Pirate Boreas Brocade Canary 21 Center Stage Chinese Dragon Chromatella Corsair Daedalus Damask Dare Devil Demetra Eldorado Flambeau Gauguin Gold Sovereign Golden Bowl Golden Era Golden Experience Golden Finch Golden Hind Golden Isle Golden Mandarin Golden Vanity 22 Happy Days Harvest Hélène Martin Helios Hephestos Hesperus Icarus Infanta Iphigenia Kronos L‘Espérance L‘Aurore La Lorraine Leda Madame Louis Henry Marchioness Marie Laurencin Mine d‘Or Mystery Narcissus 23 Nike Orion P. delavayi rot P. delavayi orange P. ludlowii P. lutea P. -

Seneca: Apocolocyntosis Free

FREE SENECA: APOCOLOCYNTOSIS PDF Lucius Annaeus Seneca,P.T. Eden,P. E. Easterling,Philip Hardie,Richard Hunter,E. J. Kenney | 192 pages | 27 Apr 1984 | CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780521288361 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom SENECA THE YOUNGER, Apocolocyntosis | Loeb Classical Library Rome,there have been published many other editions and also many translations. The following are specially noteworthy:. The English translation with accompanying largely plain text by W. Graves appended a translation to his Claudius the GodLondon The Satire of Seneca on the Apotheosis of Claudius. Ball, New York,has introduction, notes, and translation. Weinreich, Berlin, with German translation. Bibliographical surveys : M. Coffey, Seneca: Apocolocyntosis, Apocol. More Contact Us How to Subscribe. Search Publications Pages Publications Seneca: Apocolocyntosis. Advanced Search Help. Go To Section. Find in a Library View cloth edition. Print Email. Hide annotations Display: View facing pages View left- hand pages View right-hand pages Enter full screen mode. Eine Satire des Annaeus SenecaF. Buecheler, Symbola Philologorum Bonnensium. Leipzig, —Seneca: Apocolocyntosis. Petronii Saturae et liber Priapeorumed. Heraeus, ; and edition 6, revision and augmentation by W. Heraeus, Annaei Senecae Divi Claudii Apotheosis. Seneca: Apocolocyntosis, Bonn, Waltz, text and French translation and notes. Seneca, Apokolokyntosis Inzuccatura del divo Claudio. Text and Italian translation A. Rostagni, Seneca: Apocolocyntosis, Senecae Apokolokyntosis. Text, critical notes, and Italian translation. A Ronconi, Milan, Filologia Latina. Introduction, Seneca: Apocolocyntosis, and critical notes, Italian translation, and copious commentary, bibliography, and appendix. This work contains much information. A new text by P. Eden is expected. Sedgwick advises for various allusions to read also some account of Claudius. That advice indeed is good. -

The Golden Age of Athens Bellringer: According to Pericles, What Attributes Made Athens Great?

The Golden Age of Athens Bellringer: According to Pericles, what attributes made Athens great? “...we have not forgotten to provide for our weary spirits many relaxations from toil; we have regular games and sacrifices throughout the year; our homes are beautiful and elegant; and the delight which we daily feel in all these things helps to banish sorrow. Because of the greatness of our city, the fruits of the whole earth flow in upon us; so that we enjoy the goods of other countries as freely as our own...To sum up: I say that Athens is the school of Hellas (Greece)...Such is the city for whose sake these men nobly fought and died…” - Pericles, Funeral Oration, in History of the Peloponnesian Wars by Thucydides Bellringer According to what we learned yesterday, why was the time period we’re studying considered a “Golden Age” for Athens? Bellringer The Greeks had contact with many different cultures throughout the ancient world. How did the Egyptians influence Greek culture? FLASHBACK! Why was the development of AGRICULTURE and DOMESTICATION of animals important? How did it change the way humans lived? Objective I can describe the Golden Age of Athens Bellringer After the events of the Persian Wars, Athens was in a state of destruction and had been ruthlessly destroyed by the armies of Xerxes. However, the years following the wars were a “golden age” for Athens. Why might this have happened? Objective I can analyze secondary sources about Ancient Greece The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization ● Pay attention and be respectful ● As you watch, answer the analysis questions (front side) ● Identify important people mentioned throughout (back side) The Parthenon: Design and Architecture ● Pay attention and be respectful ● As you watch, record contributions of Athenian culture to the US ● Differences of building techniques/Similarities between artisans ● Answer Analysis questions Learning Target Review Guide and Learning Stations ● Get your laptop from the cart. -

Tammuz Pan and Christ Otes on a Typical Case of Myth-Transference

TA MMU! PA N A N D C H R IST O TE S O N A T! PIC AL C AS E O F M! TH - TR ANS FE R E NC E AND DE VE L O PME NT B! WILFR E D H SC HO FF . TO G E THE R WIT H A BR IE F IL L USTR ATE D A R TIC L E O N “ PA N T H E R U STIC ” B! PAU L C AR US “ " ' u n wr a p n on m s on u cou n r , s n p r n u n n , 191 2 CHIC AGO THE O PE N CO URT PUBLISHING CO MPAN! 19 12 THE FA N F PRAXIT L U O E ES. a n t Fr ticpiccc o The O pen C ourt. TH E O PE N C O U RT A MO N TH L! MA GA! IN E Devoted to th e Sci en ce of Religion. th e Relig ion of Science. and t he Exten si on of th e Religi on Periiu nen t Idea . M R 1 12 . V XX . P 6 6 O L. VI o S T B ( N . E E E , 9 NO 7 Cepyricht by The O pen Court Publishing Gumm y, TA MM ! A A D HRI T U , P N N C S . NO TES O N A T! PIC AL C ASE O F M! TH-TRANSFERENC E AND L DEVE O PMENT. W D H H FF. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Heidi Savage April 2017 Kypris, Aphrodite, Venus, and Puzzles About Belief My Aim in This Paper Is to Show That the Existence Of

Heidi Savage April 2017 Kypris, Aphrodite, Venus, and Puzzles About Belief My aim in this paper is to show that the existence of empty names raise problems for the Millian that go beyond the traditional problems of accounting for their meanings. Specifically, they have implications for Millian strategies for dealing with puzzles about belief. The standard move of positing a referent for a mythical name to avoid the problem of meaning, because of its distinctly Millian motivation, implies that solving puzzles about belief, when they involve empty names, do in fact require reliance on Millianism after all. 1. Introduction The classic puzzle about belief involves a speaker who lacks knowledge of certain linguistic facts, specifically, knowledge that two distinct names refer to one and the same object -- that they are co-referential. Because of this lack of knowledge, it becomes possible for a speaker to maintain conflicting beliefs about the object in question. This becomes puzzling when we consider the idea that co-referential terms ought to be intersubstitutable in all contexts without any change in meaning. But belief puzzles show not only that this is false, but that it can actually lead to attributing contradictory beliefs to a speaker. The question, then, is what underlying assumption is causing the puzzle? The most frequent response has been to simply conclude that co-referentiality does not make for synonymy. And this conclusion, of course, rules out the Millian view of names – that the meaning of a name is its referent. Kripke, however, argues that belief puzzles are independent any particularly Millian assumptions. -

The Hercules Story Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE HERCULES STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin W. Bowman | 128 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752450810 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom The Hercules Story PDF Book More From the Los Angeles Times. The god Apollo. Then she tried to kill the baby by sending snakes into his crib. Hercules was incredibly strong, even as a baby! When the tasks were completed, Apollo said, Hercules would become immortal. Deianira had a magic balm which a centaur had given to her. July 23, Hercules was able to drive the fearful boar into snow where he captured the boar in a net and brought the boar to Eurystheus. Greek Nyx: The Goddess of the Night. Eurystheus ordered Hercules to bring him the wild boar from the mountain of Erymanthos. Like many Greek gods, Poseidon was worshiped under many names that give insight into his importance Be on the lookout for your Britannica newsletter to get trusted stories delivered right to your inbox. Athena observed Heracles shrewdness and bravery and thus became an ally for life. The name Herakles means "glorious gift of Hera" in Greek, and that got Hera angrier still. Feb 14, Alexandra Dantzer. History at Home. Hercules was born a demi-god. On Wednesday afternoon, Sorbo retweeted a photo of some of the people who swarmed the U. Hercules could barely hear her, her whisper was that soft, yet somehow, and just as the Oracle had predicted to herself, Hera's spies discovered what the Oracle had told him. As he grew and his strength increased, Hera was evermore furious. -

The Imperial Cult and the Individual

THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Ancient Mediterranean Studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CLAIRE McGRAW Dr. Dennis Trout, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME presented by Claire McGraw, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________________________ Professor Dennis Trout _______________________________________________ Professor Anatole Mori _______________________________________________ Professor Raymond Marks _______________________________________________ Professor Marcello Mogetta _______________________________________________ Professor Sean Gurd DEDICATION There are many people who deserve to be mentioned here, and I hope I have not forgotten anyone. I must begin with my family, Tom, Michael, Lisa, and Mom. Their love and support throughout this entire process have meant so much to me. I dedicate this project to my Mom especially; I must acknowledge that nearly every good thing I know and good decision I’ve made is because of her. She has (literally and figuratively) pushed me to achieve this dream. Mom has been my rock, my wall to lean upon, every single day. I love you, Mom. Tom, Michael, and Lisa have been the best siblings and sister-in-law. Tom thinks what I do is cool, and that means the world to a little sister. -

Apocolocyntosis De Providentia

Sêneca Apocolocyntosis De Providentia Belo Horizonte FALE/UFMG 2010 Diretor da Faculdade de Letras Sumário Luiz Francisco Dias Vice-Diretor Introdução . 5 Sandra Bianchet Heloísa Maria Moraes Moreira Penna Comissão editorial Apocolocyntosis Divi Clavdii / Apocoloquintose . 8 Eliana Lourenço de Lima Reis De Providentia / Da Providência . 35 Elisa Amorim Vieira Lucia Castello Branco Maria Cândida Trindade Costa de Seabra Maria Inês de Almeida Sônia Queiroz Capa e projeto gráfico Glória Campos Mangá – Ilustração e Design Gráfico Revisão e normalização Eduardo de Lima Soares Taís Moreira Oliveira Formatação Eduardo de Lima Soares Janaína Sabino Revisão de provas Martha M. Rezende Ramon de Araújo Gomes Endereço para correspondência FALE/UFMG – Setor de Publicações Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627 – sala 2015A 31270-901 – Belo Horizonte/MG Telefax: (31) 3409-6007 e-mail: [email protected] Introdução Na literatura latina, há diversos escritores que muito produziram e influenciaram as gerações posteriores com inúmeras e densas obras. Impressionam até hoje a prosa moral de Cícero, a irreverência lírica de Catulo, a grandiosidade épica de Virgílio, o rigor formal de Horácio, a ousadia contemporânea de Ovídio e a potência filosófica e trágica de Sêneca, só para citar alguns dos grandes nomes dessa literatura abrangente. É desse último autor de textos filosóficos, dramáticos e satíricos que vamos tratar na presente publicação. Lúcio Aneu Sêneca é um dos escritores mais lidos e comentados da literatura latina. Seus textos têm conteúdo atemporal por tratarem da alma humana, dos problemas que a afligem em qualquer época, e por servirem de conselheiros aos espíritos atormentados pelas questões existenciais. É fato que nascera numa época privilegiada e que tirara disso grande proveito: após a chamada Idade de Ouro da literatura latina, em que figuraram poetas de obras imortais, tais como Virgílio, Horácio, Propércio, Tibulo e Ovídio. -

Two Cases of the Golden Age: the Hesiodic Utopia and the Platonic Ideal State

TWO CASES OF THE GOLDEN AGE: THE HESIODIC UTOPIA AND THE PLATONIC IDEAL STATE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY GÜNEŞ VEZİR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY SEPTEMBER 2019 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sadettin Kirazcı Director (Acting) I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Prof. Dr. Halil Turan Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Prof. Dr. Halil Turan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Dr. Barış Parkan (METU, PHIL) Prof. Dr. Halil Turan (METU, PHIL) Assist. Prof. Dr. Refik Güremen (Mimar Sinan Fine Arts Uni., PHIL) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: Güneş Vezir Signature : iii ABSTRACT TWO CASES OF THE GOLDEN AGE: THE HESIODIC UTOPIA AND THE PLATONIC IDEAL STATE Vezir, Güneş MA, Department of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Halil Turan September 2019, 119 pages This study was prepared to give information about the Golden Age myth, and in this regard, to illustrate for what purposes and in which ways the myth is used by Hesiod and Plato and the interaction and similarities between these thinkers. -

Greek Mythology

Greek Mythology The Creation Myth “First Chaos came into being, next wide bosomed Gaea(Earth), Tartarus and Eros (Love). From Chaos came forth Erebus and black Night. Of Night were born Aether and Day (whom she brought forth after intercourse with Erebus), and Doom, Fate, Death, sleep, Dreams; also, though she lay with none, the Hesperides and Blame and Woe and the Fates, and Nemesis to afflict mortal men, and Deceit, Friendship, Age and Strife, which also had gloomy offspring.”[11] “And Earth first bore starry Heaven (Uranus), equal to herself to cover her on every side and to be an ever-sure abiding place for the blessed gods. And earth brought forth, without intercourse of love, the Hills, haunts of the Nymphs and the fruitless sea with his raging swell.”[11] Heaven “gazing down fondly at her (Earth) from the mountains he showered fertile rain upon her secret clefts, and she bore grass flowers, and trees, with the beasts and birds proper to each. This same rain made the rivers flow and filled the hollow places with the water, so that lakes and seas came into being.”[12] The Titans and the Giants “Her (Earth) first children (with heaven) of Semi-human form were the hundred-handed giants Briareus, Gyges, and Cottus. Next appeared the three wild, one-eyed Cyclopes, builders of gigantic walls and master-smiths…..Their names were Brontes, Steropes, and Arges.”[12] Next came the “Titans: Oceanus, Hypenon, Iapetus, Themis, Memory (Mnemosyne), Phoebe also Tethys, and Cronus the wily—youngest and most terrible of her children.”[11] “Cronus hated his lusty sire Heaven (Uranus). -

The Mythological Image of the Prince in the Comedia of the Spanish Golden Age

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2014 STAGING THESEUS: THE MYTHOLOGICAL IMAGE OF THE PRINCE IN THE COMEDIA OF THE SPANISH GOLDEN AGE Whitaker R. Jordan University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jordan, Whitaker R., "STAGING THESEUS: THE MYTHOLOGICAL IMAGE OF THE PRINCE IN THE COMEDIA OF THE SPANISH GOLDEN AGE" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/15 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known.