Richard Wagner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Durch Mitleid Wissend”

“Durch Mitleid wissend” William Kinderman. Wagner’s Parsifal. Oxford University Press, New York, ©2013. 336.p., illus., 93 music examples. [This review first appeared in the December 2013 issue of Wagner Notes and appears here with permission of the author and of the Wagner Society of New York.] Most Wagnerians, amateurs and professionals alike, are sick and tired of being reminded of the darkly embarrassing links that connect their hero to Adolf Hitler. For many, the very name of the German dictator constitutes a disquieting irritant that thoroughly spoils their appreciation of Wagner’s music dramas. They argue, not without reason, that the creator of the Ring tetralogy, of Die Meistersinger, and of Parsifal cannot be held responsible for what his heirs and adherents made of his work. Would that it were so simple! Admittedly, there are good reasons to believe, with Thomas Mann, that the Dresden Kapellmeister and the anarchist revolutionary of 1848/49, had he lived to see it, would have opposed National Socialism and gone into exile, as Mann himself did in 1933. Mann left Germany because, ironically, he was viciously attacked for having besmirched the reputation of the composer, the supreme cultural icon of the opponents of the Weimar Republic on the Right and, as luck would have it, the idol of the Führer. But it cannot be denied that the nationalist and racist spin put on Parsifal is not entirely delusional and that such an interpretation was advanced well before 1933. Wagner’s “last card,” as he jokingly described it, does indeed contain a number of mystifying elements which, with a little bending of the evidence, do lend themselves to ideology-driven appropriation, especially given his many vehement pronouncements about both Germans and Jews. -

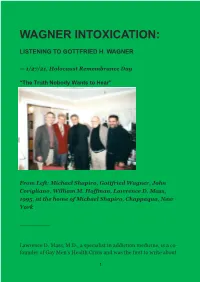

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

From Page to Stage: Wagner As Regisseur

Wagner Ia 5/27/09 3:55 PM Page 3 Copyrighted Material From Page to Stage: Wagner as Regisseur KATHERINE SYER Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to pro- duction matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flour- ished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage produc- tion in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increas- ingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production. -

Was Hitler a Darwinian?

Was Hitler a Darwinian? Robert J. Richards The University of Chicago The Darwinian underpinnings of Nazi racial ideology are patently obvious. Hitler's chapter on "Nation and Race" in Mein Kampf discusses the racial struggle for existence in clear Darwinian terms. Richard Weikart, Historian, Cal. State, Stanislaus1 Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that's almost in shape of a camel? Shakespeare, Hamlet, III, 2. 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Issues regarding a Supposed Conceptually Causal Connection . 4 3. Darwinian Theory and Racial Hierarchy . 10 4. The Racial Ideology of Gobineau and Chamberlain . 16 5. Chamberlain and Hitler . 27 6. Mein Kampf . 29 7. Struggle for Existence . 37 8. The Political Sources of Hitler’s Anti-Semitism . 41 9. Ethics and Social Darwinism . 44 10. Was the Biological Community under Hitler Darwinian? . 46 11. Conclusion . 52 1. Introduction Several scholars and many religiously conservative thinkers have recently charged that Hitler’s ideas about race and racial struggle derived from the theories of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), either directly or through intermediate sources. So, for example, the historian Richard Weikart, in his book From Darwin to Hitler (2004), maintains: “No matter how crooked the road was from Darwin to Hitler, clearly Darwinism and eugenics smoothed the path for Nazi ideology, especially for the Nazi 1 Richard Weikart, “Was It Immoral for "Expelled" to Connect Darwinism and Nazi Racism?” (http://www.discovery.org/a/5069.) 1 stress on expansion, war, racial struggle, and racial extermination.”2 In a subsequent book, Hitler’s Ethic: The Nazi Pursuit of Evolutionary Progress (2009), Weikart argues that Darwin’s “evolutionary ethics drove him [Hitler] to engage in behavior that the rest of us consider abominable.”3 Other critics have also attempted to forge a strong link between Darwin’s theory and Hitler’s biological notions. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Wagner Quarterly 157 June 2020

WAGNER SOCIETY nsw ISSUE NO 30 CELEBRATING THE MUSIC OF RICHARD WAGNER WAGNER QUARTERLY 157 JUNE 2020 Ca’ Vendramin Calergi, Venice in 1870. Photograph by Carlo Naya inscribed to Marie-Caroline de Bourbon-Sicile, duchess de Berry (1798-1870), its former owner. Wagner died here on 13 February 1883 SOCIETY’S OBJECTIVES To promote the music of Richard Wagner and his contemporaries and to encourage a wider understanding of their work. To support the training of young Wagnerian or potential Wagnerian performers from NSW. The Wagner Society In New South Wales Inc. Registered Office75 Birtley Towers, Birtley Place, Elizabeth Bay NSW 2011 Print Post Approved PP100005174 June Newsletter Issue 30 / 157 1 WAGNER IN ITALY REFER TO PETER BASSETT’S ARTICLE ON PAGES 5-10 Teatro di San Carlo, Naples Wagner by Pierre Auguste Renoir Palatine Chapel, Palermo 2 June Newsletter Issue 30 / 157 PRESIDENT’S REPORT PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2020 has been a difficult year so far, with some unexpected Thanks to the sterling efforts of Lis Bergmann, with input and unfortunate interruptions to our program. from Leona Geeves and Marie Leech, the Wagner Society in NSW now posts material on YouTube. It includes lists of We had planned a number of events but were frustrated by artists supported by the Society, videos taken by individual Covid-19 regulations preventing the Society from holding members and information on recordings and performances meetings. We have missed out on a talk by Tabatha McFadyen of particular interest to anyone interested in Wagner’s and on presentations by Antony Ernst and Peter Bassett, two compositions. -

From Humanism to Nazism: Antiquity in the Work of Houston Stewart Chamberlain

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 11 | 2015 Expressions of Environment in Euroamerican Culture / Antique Bodies in Nineteenth Century British Literature and Culture From Humanism to Nazism: Antiquity in the Work of Houston Stewart Chamberlain Johann Chapoutot Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/6680 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.6680 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Johann Chapoutot, “From Humanism to Nazism: Antiquity in the Work of Houston Stewart Chamberlain ”, Miranda [Online], 11 | 2015, Online since 23 July 2015, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/6680 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.6680 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. From Humanism to Nazism: Antiquity in the Work of Houston Stewart Chamberlain 1 From Humanism to Nazism: Antiquity in the Work of Houston Stewart Chamberlain Johann Chapoutot 1 Houston Stewart Chamberlain was a typical member of the 19th century British gentry but had the most atypical destiny―a destiny which was built around the culture of two countries: England which he left early and Germany which was to become his true home. The son of a naval officer―his father was an admiral in the Royal Navy –, he spent his whole youth travelling around Europe. After attending a lycée in Versailles and a boarding school in Cheltenham, he visited destination spas and various health resorts―he did not have a very sound constitution―with his chaperon and a tutor. -

Cosima Wagner, Brustbild Von Unbekanntem Fotograf, O

Wagner, Cosima lived in Berlin until the composer Richard Wagner invi- ted them to join him in Munich and assist him in perfor- mances of his works. It was in Munich that Cosima von Bülow left her husband, joining Richard Wagner in Trib- schen near Lucerne in Switzerland in 1868. They subse- quently married and in 1872 they moved with their child- ren to Bayreuth where Richard Wagner was planning his festival theatre. This opened in 1876 and since then has been devoted exclusively to Richard Wagner’s works. Co- sima Wagner remained resident in Bayreuth until her death. Biography The background and biography of the “Mistress of Bay- reuth”, the “Keeper of the Grail” or “Meisterin”, as Cosi- ma Wagner was variously called, were sensational. Her birth was the result of a love affair between the Countess Marie d’Agoult and the famous pianist and composer Franz Liszt. She herself rushed into an ill-considered marriage with the conductor Hans von Bülow in 1857 (“how it came about that we married is something I still don’t know … the wedding happened without any mood, motion or consideration on my part”). She wrote articles for a French newspaper, played the piano (although an excellent pianist, she never performed in public), atten- ded concerts, operas and plays, and was not merely high- ly gifted artistically, but also very interested in cultural matters. Then the composer Richard Wagner fell in love Cosima Wagner, Brustbild von unbekanntem Fotograf, o. D. with Cosima – 24 years his junior – and she reciproca- ted. The ensuing years were agonizing, as she was still of- Cosima Wagner ficially von Bülow’s wife and was the mother of his two Birth name: Cosima Francesca Gaetana de Flavigny children (Daniela and Blandine). -

The Effect of Richard Wagner's Music and Beliefs on Hitler's Ideology

Musical Offerings Volume 7 Number 2 Fall 2016 Article 1 9-2016 The Effect of Richard Wagner's Music and Beliefs on Hitler's Ideology Carolyn S. Ticker Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the European History Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Ticker, Carolyn S. (2016) "The Effect of Richard Wagner's Music and Beliefs on Hitler's Ideology," Musical Offerings: Vol. 7 : No. 2 , Article 1. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2016.7.2.1 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol7/iss2/1 The Effect of Richard Wagner's Music and Beliefs on Hitler's Ideology Document Type Article Abstract The Holocaust will always be remembered as one of the most horrific and vile events in all of history. One question that has been so pervasive in regards to this historical event is the question of why. Why exactly did Hitler massacre the Jewish people? Why did he come to the conclusion that the Jews were somehow lesser than him, and that it was okay to kill them? What and who were his influences and how did they help form Hitler’s opinions leading up to the Holocaust? Although more than one situation or person influenced Hitler, I believe that one man in particular really helped contribute to Hitler’s ideas, especially about the Jewish people. -

Houston Stewart Chamberlain

HOUSTON STEWART CHAMBERLAIN COSIMA WAGNER, NÉE DE FLAVIGNY ANNA CHAMBERLAIN, NÉE HORST 1855-1927 1837 - 1930 1846 - 1924 English writer, private scholar, German by choice, Illegitimate daughter of Marie d’Agoult and Franz Met Chamberlain in Cannes in 1874, married in anti-Semite. After breaking off his scientific Liszt, married from 1857 to 1869 to the conductor Geneva in 1878, no children. The couple lived studies, he contacted the Wagner family, Hans von Bülow, two daughters: Daniela and in Geneva and Dresden. In 1905, Chamberlain separated from his first wife Anna Horst and Blandine. From 1863 on, love affair with Richard separated from Anna by letter, refused direct married Eva Wagner in 1908. The Foundations of Wagner, whom she married in 1870, three contact from that time on and communicated the 19th Century, his main work on race theory, illegitimate children: Isolde, Eva and Siegfried. with her only through a lawyer. In 1905 last was an influential bestseller in the early 20th After Wagner’s death in 1883, she directed the meeting when visiting Anna’s sickbed. The century. Bayreuth Festival until 1907. marriage was divorced in 1906. SIEGFRIED “FIDI” WAGNER WINIFRED WAGNER, NÉE WILLIAMS EVA CHAMBERLAIN, NÉE VON BÜLOW 1869 - 1930 1897 - 1980 1867 -1942 English orphan, festival director 1930 - 1944. Composer and conductor, youngest child Wagner’s second daughter, wife of Houston Her adoptive father, the Wagnerian and Wagner and only son of Richard Wagner, homosexual. Chamberlain (marriage: 1908 - 1927) and an friend Karl Klindworth, with whom she grew up Besides his engagement for the Bayreuth enthusiastic National Socialist. -

Famous Composer Richard Wagner in Bayreuth

today 1883 1872 Richard Wagner conducts Beethovens ninth Synphonie on 22 May The Festival Theatre 1876 (G. Bechstein) The funeral procession with Wagner‘s casket, 18.2.1883 World Heritage Opera House Festspielhaus on the Green Hill Arrival at the Station Richard-Wagner-Stops in Bayreuth Tourist-Information Richard Wagner’s Tannhäuser was performed here already in 1860, in the Nowhere else in the world is there an opera house built specifically for the When Wagner and his family moved to Bayreuth in 1872, they arrived at Festspielhaus Richard Wagner Museum Tourist-Information presence of King Maximilian II of Bavaria. And in 1870, when Wagner was works of just one composer. This was a dream that Richard Wagner had to the old railway station. In 1876, the year of the first Festspiele, the second Villa Wahnfried Trustees: & Bayreuth Shop still living in the Villa Tribschen in Switzerland and was on the lookout for a fight for. In those days copyright was still in its infancy and many theatres laid railway line connecting Bayreuth to Nuremberg and the new station were Festival House Richard-Wagner-Stiftung Bayreuth Opernstrasse 22 / 95444 Bayreuth venue for his Festspiele, the conductor Hans Richter recommended it to him on performances with almost no rehearsals at all and singers who were not still under construction. They finally opened in 1879, and Cosima noted in Grüner Hügel Director: Dr. Sven Friedrich Tel. +49-(0)921-885 88 on account of its unusually large stage. But when Richard and Cosima visited particularly good at singing, let alone acting. Musicians were paid servants’ her diary entry for 23 September: “Drank beer at the new station, which R. -

The Wagner Anniversary in Germany and Switzerland Dagny Beidler and Eva Rieger

2015 © Dagny Beidler and Eva Rieger, Context 39 (2014): v–vii. INTRODUCTION The Wagner Anniversary in Germany and Switzerland Dagny Beidler and Eva Rieger In recognition of Richard Wagner’s bicentennial in 2013 there were innumerable conferences, celebrations, concerts, TV documentaries and newly published books in Germany and Switzerland, those being the two countries where Richard Wagner mainly spent his life. Our report can only be an incomplete survey. Let us begin with Switzerland. The first item on the Wagner agenda took place in February with a production of Tannhäuser at the Zurich Opera. Nina Stemme was a fabulous Elisabeth and Michael Volle an outstanding Wolfram in a fairly good production. On April 16, the Lord Mayor of Zurich opened an exhibition on Franz W. Beidler, the eldest grandson of Richard Wagner and a Swiss citizen. It covered a large part of Wagner’s first daughter Isolde’s life and showed what had become of the Swiss Wagner family branch after Franz W. Beidler left Germany in 1933. This exhibition—which included hitherto unknown photos and documents—was shown again in Bayreuth in 2014 and in Tribschen near Lucerne a year later. The Swiss annual music festival, which is held in Zurich in June, was full of Wagner- related events. The overall programme—titled The Greenhouse … (a reference to Mathilde and Otto Wesendonck’s orangery)—included concerts with early works of the master, plays with references to Wagner, and artworks. The festival was opened by the composer’s great- granddaughter Nike Wagner who gave a fascinating but also humorous speech on Wagner’s time in exile in Switzerland, showing parallels to the situation today.