Richard Wagner's “Wesendonck Lieder”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRISTAN UND MATHILDE Inspiration – Werk – Rezeption

TRISTAN UND MATHILDE Inspiration – Werk – Rezeption Sonderausstellung 29. 11. 2014 bis 11. 01. 2015 Stadtschloss Eisenach 2 / 3 Nicolaus J. Oesterlein (1841–1898), Sammler und Initiator der Sammlung DIE EISENACHER RICHARD-WAGNER-SAMMLUNG In der Reuter-Villa am Fuße der Wartburg schlummern manch vergessene Schätze: Das Abbild einer römischen Villa beherbergt die zweitgrößte Richard-Wagner-Sammlung der Welt. Den Grundstein hierfür legte der glühende Wagner-Verehrer Nicolaus J. Oesterlein (1841–1898) mit einer akribisch angelegten Sammlung von ca. 25.000 Objekten – darunter etwa 200 Handschriften und Originalbriefe Wagners, 700 Theaterzettel, 1000 Graphiken und Fotos, 15.000 Zeitungsausschnitte, handgeschriebene Partituren. Das Herzstück der Sammlung ist eine über 5.500 Bücher umfassende Bibliothek, die neben sämtlichen Wer- ken des Komponisten den fast lückenlosen Bestand der Wagner-Sekundärliteratur des 19. Jahrhunderts enthält. Das Archivmaterial stellt nicht nur einen umfassenden Zugang zu Wagners kompositori- schem und literarischem Schaffen dar, sondern ebenso zu musikästhetischen, philoso- phischen, kulturgeschichtlichen und soziopolitischen Kontroversen des späten 19. Jahr- hunderts. Oesterleins Sammlung kann somit als ein Spiegelbild der Wagner-Rezeption gedeutet werden. Die Sonderausstellung »Tristan und Mathilde. Inspiration – Werk – Rezeption« rückt einige der exquisiten Exemplare aus der Sammlung erstmals wieder in die Öffentlichkeit, die auf diese Weise mit diesem unschätzbaren Kulturgut konfrontiert werden soll. Wie die Sammlung nach Eisenach kam In den 1870er Jahren begann Nicolaus J. Oesterlein mit einem enormen finanziellen Auf- wand und einer fast manischen Akribie alles zu sammeln, was mit dem Komponisten in Verbindung stand. 1887 eröffnete Oesterlein ein Privatmuseum in Wien – in den 1890er Jahren brachte er seinen vierbändigen Katalog heraus. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt umfasste seine Sammlung – nach eigenen Angaben – ca. -

SM358-Voyager Quartett-Book-Lay06.Indd

WAGNER MAHLER BOTEN DER LIEBE VOYAGER QUARTET TRANSCRIPTED AND RECOMPOSED BY ANDREAS HÖRICHT RICHARD WAGNER TRISTAN UND ISOLDE 01 Vorspiel 9:53 WESENDONCK 02 I Der Engel 3:44 03 II Stehe still! 4:35 04 III Im Treibhaus 5:30 05 IV Schmerzen 2:25 06 V Träume 4:51 GUSTAV MAHLER STREICHQUARTETT NR. 1.0, A-MOLL 07 I Moderato – Allegro 12:36 08 II Adagietto 11:46 09 III Adagio 8:21 10 IV Allegro 4:10 Total Time: 67:58 2 3 So geht das Voyager Quartet auf Seelenwanderung, überbringt klingende BOTEN DER LIEBE An Alma, Mathilde und Isolde Liebesbriefe, verschlüsselte Botschaften und geheime Nachrichten. Ein Psychogramm in betörenden Tönen, recomposed für Streichquartett, dem Was soll man nach der Transkription der „Winterreise“ als Nächstes tun? Ein Medium für spirituelle Botschaften. Die Musik erhält hier den Vorrang, den Streichquartett von Richard Wagner oder Gustav Mahler? Hat sich die Musikwelt Schopenhauer ihr zugemessen haben wollte, nämlich „reine Musik solle das nicht schon immer gewünscht? Geheimnisse künden, die sonst keiner wissen und sagen kann.“ Vor einigen Jahren spielte das Voyager Quartet im Rahmen der Bayreuther Andreas Höricht Festspiele ein Konzert in der Villa Wahnfried. Der Ort faszinierte uns über die Maßen und so war ein erster Eckpunkt gesetzt. Die Inspiration kam dann „Man ist sozusagen selbst nur ein Instrument, auf dem das Universum spielt.“ wieder durch Franz Schubert. In seinem Lied „Die Sterne“ werden eben diese Gustav Mahler als „Bothen der Liebe“ besungen. So fügte es sich, dass das Voyager Quartet, „Frauen sind die Musik des Lebens.“ das sich ja auf Reisen in Raum und Zeit begibt, hier musikalische Botschaften Richard Wagner versendet, nämlich Botschaften der Liebe von Komponisten an ihre Musen. -

Zwischen Nottaufe Und Nottrauung – Einblicke in Das Leben Felix Mottls

Clarissa Höschel Zwischen Nottaufe und Nottrauung – Einblicke in das Leben Felix Mottls . Eine Hommage zu seinem 160. Geburtstag In der Münchener Musikgeschichte hat er längst seinen festen Platz – der aus Unter St. Veit (Wien) stammende Felix Mottl (1856–1911), der von 1904 bis zu seinem Tod als Generalmusikdirektor an der Isar wirkte. Der Mensch hinter dem Musiker ist hingegen nur wenigen bekannt; selbst die anlässlich seines 150. Geburtstages erschienene Biografe1 porträtiert in erster Linie den Musi- ker. Auch anlässlich seines 100. Todestages (2011) wurde, wenn überhaupt, an den Generalmusikdirektor erinnert – Anlass genug, einige Facetten des Menschen und Mannes Felix Mottl vorzustellen. Gelingen kann ein solches Unterfangen anhand der tagebuchartigen Aufzeich- nungen, die Mottl 1873 be- gonnen hat und die heute in der Bayerischen Staats- bibliothek in München als Teil des Nachlasses Felix Abb. 1: Felix Mottl um 1900. Foto: Max Stufer Kunstverlag. Mona censia. Literaturarchiv und Bibliothek München (Sign. P / a 1129). 1 Frithjof Haas, Der Magier am Dirigentenpult, Karlsruhe 2006. Eine Rezension der Ver- fasserin fndet sich in Musik in Bayern 72 / 73 (2007 / 08), S. 248–254. 157 Clarissa Höschel Mottls aufewahrt werden.2 Mottl hat diese Aufzeichnungen zwar bis kurz vor seinem Tod geführt, doch sind sie nichts weniger als bewusst für die Nachwelt Hinterlassenes. Soweit sie im Original vorliegen, weisen sie einen sehr eigentümlichen Stil auf, denn sie bestehen, vor allem bis zu seiner New- York-Reise (1903), aus mit stichpunktartigen Notizen vollgeschriebenen Ta- schenkalendern, die meist über mehrere Jahre hinweg verwendet wurden. Mottls Schrif ist klein und unleserlich, seine Einträge sind in aller Regel kurz und knapp und bestehen of nur aus einzelnen Worten, die durch Punk- te getrennt sind. -

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please Note That This Lesson Works Best Post-Show

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please note that this lesson works best post-show Educator should choose which female character to focus on based on the opera(s) the group has attended. See below for the list of female characters in each opera: Das Rheingold: Fricka, Erda, Freia Die Walküre: Brunhilde, Sieglinde, Fricka Siegfried: Brunhilde, Erda Götterdämmerung: Brunhilde, Gutrune GRADE LEVELS 6-12 TIMING 1-2 periods PRIOR KNOWLEDGE Educator should be somewhat familiar with the female characters of the Ring AIM OF LESSON Compare and contrast the actual women in Wagner’s life to the female characters he created in the Ring OBJECTIVES To explore the female characters in the Ring by studying Wagner’s relationship with the women in his life CURRICULAR Language Arts CONNECTIONS History and Social Studies MATERIALS Computer and internet access. Some preliminary resources listed below: Brunhilde in the “Ring”: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brynhildr#Wagner's_%22Ring%22_cycle) First wife Minna Planer: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minna_Planer) o Themes: turbulence, infidelity, frustration Mistress Mathilde Wesendonck: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathilde_Wesendonck) o Themes: infatuation, deep romantic attachment that’s doomed, unrequited love Second wife Cosima Wagner: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosima_Wagner) o Themes: devotion to Wagner and his works; Wagner’s muse Wagner’s relationship with his mother: (https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/richard-wagner-392.php) o Theme: mistrust NATIONAL CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.7.9 STANDARDS/ Compare and contrast a fictional portrayal of a time, place, or character and a STATE STANDARDS historical account of the same period as a means of understanding how authors of fiction use or alter history. -

TT: * Why Richard Wagner? What´S Your Own Relationship with His Music? JN: Years Ago I Curated Some Performances of Richard

TT: * Why Richard Wagner? What´s your own relationship with his music? JN: Years ago I curated some performances of Richard Wagner in Zurich and found out that the chapter of his life in Zurich was not so well known. What is commonly known is the Wagner with the beret in Bayreuth and the face of the old master. Even the Swiss people are not aware of his 9 years in Zurich between 1849-1858 and then later in Lucerne. The Zurich period of his life is, in my opinion, the most important, because he wrote the manuscripts of his most important operas, meaning the libretti, including Parsifal and he composed two parts of The Ring, Tristan and Isolde and The Wesendonck Songs. We know now that Tristan and Isolde is the entrance to modernity in music history and the mysteries behind development is the story of our film. In his youth until his fortieth birthday, Richard Wagner was a radical democrat and anarchist. After a failed German revolution, he lived in Zurich together with his german friends in exile under the protection of the Zurich community. My relationship with his music is that mostly I cannot enjoy it, because what we hear in older recordings and now in concert halls is too loud and overwhelming the poetry of his words and thoughts are mostly lost. If you go deeper into his scripts and life, you realize that this is a problem since the first performances in his lifetime. Wagner wasn´t happy with the results in theatre, he would´ve liked to create real poetic drama, where you can understand the music like a language together with pictures and movements, he called it the „Gesamtkunstwerk“. -

“Durch Mitleid Wissend”

“Durch Mitleid wissend” William Kinderman. Wagner’s Parsifal. Oxford University Press, New York, ©2013. 336.p., illus., 93 music examples. [This review first appeared in the December 2013 issue of Wagner Notes and appears here with permission of the author and of the Wagner Society of New York.] Most Wagnerians, amateurs and professionals alike, are sick and tired of being reminded of the darkly embarrassing links that connect their hero to Adolf Hitler. For many, the very name of the German dictator constitutes a disquieting irritant that thoroughly spoils their appreciation of Wagner’s music dramas. They argue, not without reason, that the creator of the Ring tetralogy, of Die Meistersinger, and of Parsifal cannot be held responsible for what his heirs and adherents made of his work. Would that it were so simple! Admittedly, there are good reasons to believe, with Thomas Mann, that the Dresden Kapellmeister and the anarchist revolutionary of 1848/49, had he lived to see it, would have opposed National Socialism and gone into exile, as Mann himself did in 1933. Mann left Germany because, ironically, he was viciously attacked for having besmirched the reputation of the composer, the supreme cultural icon of the opponents of the Weimar Republic on the Right and, as luck would have it, the idol of the Führer. But it cannot be denied that the nationalist and racist spin put on Parsifal is not entirely delusional and that such an interpretation was advanced well before 1933. Wagner’s “last card,” as he jokingly described it, does indeed contain a number of mystifying elements which, with a little bending of the evidence, do lend themselves to ideology-driven appropriation, especially given his many vehement pronouncements about both Germans and Jews. -

Modernist Permabulations Through Time and Space

Journal of the British Academy, 4, 197–219. DOI 10.5871/jba/004.197 Posted 18 October 2016. © The British Academy 2016 Modernist perambulations through time and space: From Enlightened walking to crawling, stalking, modelling and street-walking Lecture in Modern Languages read 19 May 2016 ANNE FUCHS Fellow of the Academy Abstract: Analysing diverse modes of walking across a wide range of texts from the Enlightenment period and beyond, this article explores how the practice of walking was discovered by philosophers, educators and writers as a rich discursive trope that stood for competing notions of the morally good life. The discussion proceeds to then investigate how psychological, philosophical and moral interpretations of bad prac- tices of walking in particular resurface in texts by Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann and the interwar writer Irmgard Keun. It is argued that literary modernism transformed walking from an Enlightenment trope signifying progress into the embodiment of moral and epistemological ambivalence. In this process, walking becomes an expression of the disconcerting experience of modernity. The paper concludes with a discussion of walking as a gendered performance: while the male walkers in the modernist texts under discussion suffer from a bad gait that leads to ruination, the new figure of the flâneuse manages to engage in pleasurable walking by abandoning the Enlightenment legacy of the good gait. Keywords: modes of walking, discursive trope, Enlightenment discourse, modernism, modernity, moral and epistemological ambivalence, gender, flâneuse. Walking on one’s two legs is an essential but ordinary skill that, unlike cycling, skate-boarding, roller-skating or ballroom dancing, does not require special proficiency, aptitude or thought—unless, of course, we are physically impaired. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

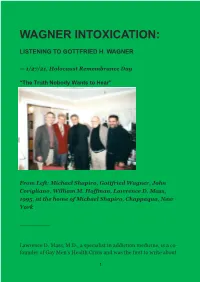

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

Mass Culture and Individuality in Hermann Broch’S Late Works

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sunderland University Institutional Repository MASS CULTURE AND INDIVIDUALITY IN HERMANN BROCH’S LATE WORKS JANET PEARSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Sunderland for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. APRIL 2015 i Abstract Mass Culture and Individuality in Hermann Broch’s Late Works Janet Pearson This thesis explores Hermann Broch’s thought regarding the relationship between the individual and the mass, in an age of mass-culture. Broch, an Austrian-Jewish intellectual, who emigrated to America in 1938, discussed ideas upon this theme in theoretical essays, including a theory of mass hysteria (Massenwahntheorie) as well as his fictional The Death of Virgil (Der Tod des Vergil). In the study, the analysis of his theoretical work shows that Broch’s views regarding the masses differ from those of other theorists contemporary to him (Le Bon, Freud and Canetti), in that they are closely linked to his theory of value. It also establishes that his ideas about individuality reach back to the earliest philosophers, and that he perceived this dimension of human existence to be changing, through the development of ‘ego- consciousness’. Building upon this, the textual analysis of the Virgil demonstrates that Broch finds similarities between his own era and the age of Augustus, but also indicates that the concept of individuality portrayed in the work goes beyond that discussed in his theoretical writing and points towards a new role for art in the post-industrial age. -

The Individual and the «Spiritual» World in Kafka's Novels

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 3 8-1-1978 The Individual and the «Spiritual» World in Kafka's Novels Ulrich Fülleborn Universitat Erlangen-Niirnberg Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Fülleborn, Ulrich (1978) "The Individual and the «Spiritual» World in Kafka's Novels," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1057 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Individual and the «Spiritual» World in Kafka's Novels Abstract Following an earlier essay by the same author on 'Perspektivismus und Parabolik' in Kafka's shorter prose pieces, this article gives a description of the structure of Kafka's novels in terms of the concepts 'the individual' (cf. Kierkegaard's 'individuals') and 'the spiritual world' (Kafka: «There is no world but the spiritual one»). Joseph K. and the land-surveyor K. become individuals by leaving the world of everyday life and passing over into the incomprehensible spiritual world of trials and a village-castle community, in the same way that Karl Rossmann had passed over into the 'Nature-theatre of Oklahoma' before them. And they remain as individuals, since in this world they struggle to hold their own. -

Richard Wagner in München

Richard Wagner in München MÜNCHNER VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN ZUR MUSIKGESCHICHTE Begründet von Thrasybulos G. Georgiades Fortgeführt von Theodor Göllner Herausgegeben von Hartmut Schick Band 76 Richard Wagner in München. Bericht über das interdisziplinäre Symposium zum 200. Geburtstag des Komponisten München, 26.–27. April 2013 RICHARD WAGNER IN MÜNCHEN Bericht über das interdisziplinäre Symposium zum 200. Geburtstag des Komponisten München, 26.–27. April 2013 Herausgegeben von Sebastian Bolz und Hartmut Schick Weitere Informationen über den Verlag und sein Programm unter: www.allitera.de Dezember 2015 Allitera Verlag Ein Verlag der Buch&media GmbH, München © 2015 Buch&media GmbH, München © 2015 der Einzelbeiträge bei den AutorInnen Satz und Layout: Sebastian Bolz und Friedrich Wall Printed in Germany · ISBN 978-3-86906-790-2 Inhalt Vorwort ..................................................... 7 Abkürzungen ................................................ 9 Hartmut Schick Zwischen Skandal und Triumph: Richard Wagners Wirken in München ... 11 Ulrich Konrad Münchner G’schichten. Von Isolde, Parsifal und dem Messelesen ......... 37 Katharina Weigand König Ludwig II. – politische und biografische Wirklichkeiten jenseits von Wagner, Kunst und Oper .................................... 47 Jürgen Schläder Wagners Theater und Ludwigs Politik. Die Meistersinger als Instrument kultureller Identifikation ............... 63 Markus Kiesel »Was geht mich alle Baukunst der Welt an!« Wagners Münchener Festspielhausprojekte .......................... 79 Günter