'Winifred Wagner: a Life at the Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

“Durch Mitleid Wissend”

“Durch Mitleid wissend” William Kinderman. Wagner’s Parsifal. Oxford University Press, New York, ©2013. 336.p., illus., 93 music examples. [This review first appeared in the December 2013 issue of Wagner Notes and appears here with permission of the author and of the Wagner Society of New York.] Most Wagnerians, amateurs and professionals alike, are sick and tired of being reminded of the darkly embarrassing links that connect their hero to Adolf Hitler. For many, the very name of the German dictator constitutes a disquieting irritant that thoroughly spoils their appreciation of Wagner’s music dramas. They argue, not without reason, that the creator of the Ring tetralogy, of Die Meistersinger, and of Parsifal cannot be held responsible for what his heirs and adherents made of his work. Would that it were so simple! Admittedly, there are good reasons to believe, with Thomas Mann, that the Dresden Kapellmeister and the anarchist revolutionary of 1848/49, had he lived to see it, would have opposed National Socialism and gone into exile, as Mann himself did in 1933. Mann left Germany because, ironically, he was viciously attacked for having besmirched the reputation of the composer, the supreme cultural icon of the opponents of the Weimar Republic on the Right and, as luck would have it, the idol of the Führer. But it cannot be denied that the nationalist and racist spin put on Parsifal is not entirely delusional and that such an interpretation was advanced well before 1933. Wagner’s “last card,” as he jokingly described it, does indeed contain a number of mystifying elements which, with a little bending of the evidence, do lend themselves to ideology-driven appropriation, especially given his many vehement pronouncements about both Germans and Jews. -

Reviving Hitler's Favorite Music

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 9, Number 35, September 14, 1982 Reviving Hitler's favorite music In Seattle, the Weyerhaeuserfamily is promoting Wagner's Ring cycle as a wedgefor the "new dark age" within the U.S. , writes Mark Calney If you want to see true Wagner you must go to Seattle. greeted not by the presence of our local Northwestpatricians -Winifred Wagner in black tie, which one would expect during the German cycle, but rather the flannel shirt and denim set. There were It was precisely 106 years ago in the ancient Bavarian forest cowboys from Colorado, gays from San Francisco, the on the outskirts of the German village of Bayreuth, that the neighborhood Anglican priest, and what appeared to be the first complete cycle of Richard Wagner's The Ring of the entire anthropology department from the local university, Nibelungs was performed. It was a most regal affair. This dispersed among the crowd. I overheard conversations in was to be the unveiling of mankind's greatest artistic achieve Japanese, German, Spanish, and Texan. A number of these ment, a four-day epic opera concerning the mythical birth pilgrims came from around the world-from Switzerland, and destiny of Man, depicting his various struggles amidst a South Africa, Tasmania, Chile, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia flotsamof dragons, dwarfs, and gods. Who was to attend this from 25 different countriesand from every state in the union. festival heralding the "New Age" in Wagner's "democratic For some it was their eighth sojournto this idyllically under theater?" populated part of America, to participate in the revelries of The premier day of Das Rheingold found the Bayreuth the only festival in the world which contiguously performs theater stuffed to the rafters with every imaginable repre the German and English cycles of the Ring (14 days), and sentative of the European oligarchy from Genoa to St. -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

Beyond the Racial State

Beyond the Racial State Rethinking Nazi Germany Edited by DEVIN 0. PENDAS Boston College MARK ROSEMAN Indiana University and · RICHARD F. WETZELL German Historical Institute Washington, D.C. GERMAN lflSTORICAL INSTITUTE Washington, D.C. and CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS I Racial Discourse, Nazi Violence, and the Limits of the Racial State Model Mark Roseman It seems obvious that the Nazi regime was a racial state. The Nazis spoke a great deal about racial purity and racial difference. They identified racial enemies and murdered them. They devoted considerable attention to the health of their own "race," offering significant incentives for marriage and reproduction of desirable Aryans, and eliminating undesirable groups. While some forms of population eugenics were common in the interwar period, the sheer range of Nazi initiatives, coupled with the Nazis' willing ness to kill citizens they deemed physically or mentally substandard, was unique. "Racial state" seems not only a powerful shorthand for a regime that prioritized racial-biological imperatives but also above all a pithy and plausible explanatory model, establishing a strong causal link between racial thinking, on the one hand, and murderous population policy and genocide, on the other. There is nothing wrong with attaching "racial. state" as a descriptive label tci the Nazi regime. It successfully connotes a regime that both spoke a great deal about race and acted in the name of race. It enables us to see the links between a broad set of different population measures, some positively discriminatory, some murderously eliminatory. It reminds us how sttongly the Nazis believed that maximizing national power depended on managing the health and quality of the population. -

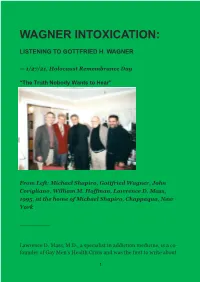

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Simon O'neill ONZM

Simon O’Neill ONZM Tenor “Simon O'Neill made a tremendous debut in the title-role, giving notice that he is the best heroic tenor to emerge over the last decade.” Rupert Christiansen, The Telegraph, UK. A native of New Zealand, Simon O’Neill is one of the finest helden-tenors on the international stage. He has frequently performed with the Metropolitan Opera, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Berlin, Hamburg and Bayerische Staatsopern, Teatro alla Scala and the Bayreuth, Salzburg, Edinburgh and BBC Proms Festivals, appearing with a number of illustrious conductors including Daniel Barenboim, Sir Simon Rattle, James Levine, Riccardo Muti, Valery Gergiev, Sir Antonio Pappano, Pietari Inkinen, Pierre Boulez, Sir Mark Elder, Sir Colin Davis, Simone Young, Edo de Waart, Fabio Luisi, Donald Runnicles, Sir Simon Rattle, Jaap Van Zweden and Christian Thielemann. Simon’s performances as Siegmund in Die Walküre at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden with Pappano, Teatro alla Scala and Berlin Staatsoper with Barenboim, at the Metropolitan Opera with Runnicles in the celebrated Otto Schenk production returning with Luisi in the Lepage Ring Cycle and in the Götz Friedrich production at Deutsche Oper Berlin with Rattle were performed to wide critical acclaim. He was described in the international press as "an exemplary Siegmund, terrific of voice", "THE Wagnerian tenor of his generation" and "a turbo-charged tenor". During this season’s engagements Simon makes his debut at: Tanglewood with the Boston Symphony and Andris Nelsons and the Toronto Symphony with Sir Andrew Davis and Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana with Henrik Nánási as Siegmund in concert performances of Die Walküre. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2012). Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century. In: Lawson, C. and Stowell, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. (pp. 643-695). Cambridge University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6305/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521896115.027 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/2654833/WORKINGFOLDER/LASL/9780521896115C26.3D 643 [643–695] 5.9.2011 7:13PM . 26 . Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century IAN PACE 1815–1848 Beethoven, Schubert and musical performance in Vienna from the Congress until 1830 As a major centre with a long tradition of performance, Vienna richly reflects -

ARSC Journal, Vol.21, No

Sound Recording Reviews Wagner: Parsifal (excerpts). Berlin State Opera Chorus and Orchestra (a) Bayreuth Festival Chorus and Orchestra (b), cond. Karl Muck. Opal 837/8 (LP; mono). Prelude (a: December 11, 1927); Act 1-Transformation & Grail Scenes (b: July/ August, 1927); Act 2-Flower Maidens' Scene (b: July/August, 1927); Act 3 (a: with G. Pistor, C. Bronsgeest, L. Hofmann; slightly abridged; October 10-11and13-14, 1928). Karl Muck conducted Parsifal at every Bayreuth Festival from 1901 to 1930. His immediate predecessor was Franz Fischer, the Munich conductor who had alternated with Hermann Levi during the premiere season of 1882 under Wagner's own supervi sion. And Muck's retirement, soon after Cosima and Siegfried Wagner died, brought another changing of the guard; Wilhelm Furtwangler came to the Green Hill for the next festival, at which Parsifal was controversially assigned to Arturo Toscanini. It is difficult if not impossible to tell how far Muck's interpretation of Parsifal reflected traditions originating with Wagner himself. Muck's act-by-act timings from 1901 mostly fall within the range defined in 1882 by Levi and Fischer, but Act 1 was decidedly slower-1:56, compared with Levi's 1:47 and Fischer's 1:50. Muck's timing is closer to that of Felix Mottl, who had been a musical assistant in 1882, and of Hans Knappertsbusch in his first and slowest Bayreuth Parsifal. But in later summers Muck speeded up to the more "normal" timings of 1:50 and 1:47, and the extensive recordings he made in 1927-8, now republished by Opal, show that he could be not only "sehr langsam" but also "bewegt," according to the score's requirements. -

From Page to Stage: Wagner As Regisseur

Wagner Ia 5/27/09 3:55 PM Page 3 Copyrighted Material From Page to Stage: Wagner as Regisseur KATHERINE SYER Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to pro- duction matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flour- ished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage produc- tion in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increas- ingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production. -

The Nuremberg Party Rallies, Wagner, and the Theatricality of Hitler And

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 Cathedral of Light: The his imagery and music by the Nazi Party.7 Hitler was obsessed with Wagnerian operas. It was the only type of Nuremberg Party Rallies, music he listened to with any enthusiasm, and he could Wagner, and The Theatricality be heard whistling it perfectly.8 He was witnessed to be visibly calmed by the music of Wagner when agitated. of Hitler and the Nazi Party According to Goebbels, Hitler had a “strong inner need Stacey Reed for art,” and was known to, in the middle of important History 395 political negotiations or tactical battles to go by himself Fall 2012 or with a few comrades, to sit in a theater and listen to “the heroically elevated measures of a Wagnerian music The National Socialist, or Nazi, Party was drama in artistic unison with his political being.”10 This keenly aware of the power of the arts, the elements of was a tendency that began long before his appointment the theatre, and the power of spectacle on the minds and as Chancellor. Already a passionate follower of Wagner's attitudes of the German people. This was especially true works, Hitler was further directed on his path towards of music, and they found fertile ground in the minds of Führer when, upon meeting Wagner's son-in-law at the people through the imagination of Richard Wagner his Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth in September, 1923, and his great, nationalistic Operas. The Nazi Party the master of the house told him that he saw in Hitler, engaged with the political philosophy of the composer Germany's savior.11 Hitler would go on to make Wagner and elevated the enjoyment of his art to a key ritual of a central part of his Nazi Mythos, incorporating his works the cult of Nazism.