Götterdämmerung (‘Twilight of the Gods’)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SM358-Voyager Quartett-Book-Lay06.Indd

WAGNER MAHLER BOTEN DER LIEBE VOYAGER QUARTET TRANSCRIPTED AND RECOMPOSED BY ANDREAS HÖRICHT RICHARD WAGNER TRISTAN UND ISOLDE 01 Vorspiel 9:53 WESENDONCK 02 I Der Engel 3:44 03 II Stehe still! 4:35 04 III Im Treibhaus 5:30 05 IV Schmerzen 2:25 06 V Träume 4:51 GUSTAV MAHLER STREICHQUARTETT NR. 1.0, A-MOLL 07 I Moderato – Allegro 12:36 08 II Adagietto 11:46 09 III Adagio 8:21 10 IV Allegro 4:10 Total Time: 67:58 2 3 So geht das Voyager Quartet auf Seelenwanderung, überbringt klingende BOTEN DER LIEBE An Alma, Mathilde und Isolde Liebesbriefe, verschlüsselte Botschaften und geheime Nachrichten. Ein Psychogramm in betörenden Tönen, recomposed für Streichquartett, dem Was soll man nach der Transkription der „Winterreise“ als Nächstes tun? Ein Medium für spirituelle Botschaften. Die Musik erhält hier den Vorrang, den Streichquartett von Richard Wagner oder Gustav Mahler? Hat sich die Musikwelt Schopenhauer ihr zugemessen haben wollte, nämlich „reine Musik solle das nicht schon immer gewünscht? Geheimnisse künden, die sonst keiner wissen und sagen kann.“ Vor einigen Jahren spielte das Voyager Quartet im Rahmen der Bayreuther Andreas Höricht Festspiele ein Konzert in der Villa Wahnfried. Der Ort faszinierte uns über die Maßen und so war ein erster Eckpunkt gesetzt. Die Inspiration kam dann „Man ist sozusagen selbst nur ein Instrument, auf dem das Universum spielt.“ wieder durch Franz Schubert. In seinem Lied „Die Sterne“ werden eben diese Gustav Mahler als „Bothen der Liebe“ besungen. So fügte es sich, dass das Voyager Quartet, „Frauen sind die Musik des Lebens.“ das sich ja auf Reisen in Raum und Zeit begibt, hier musikalische Botschaften Richard Wagner versendet, nämlich Botschaften der Liebe von Komponisten an ihre Musen. -

“Durch Mitleid Wissend”

“Durch Mitleid wissend” William Kinderman. Wagner’s Parsifal. Oxford University Press, New York, ©2013. 336.p., illus., 93 music examples. [This review first appeared in the December 2013 issue of Wagner Notes and appears here with permission of the author and of the Wagner Society of New York.] Most Wagnerians, amateurs and professionals alike, are sick and tired of being reminded of the darkly embarrassing links that connect their hero to Adolf Hitler. For many, the very name of the German dictator constitutes a disquieting irritant that thoroughly spoils their appreciation of Wagner’s music dramas. They argue, not without reason, that the creator of the Ring tetralogy, of Die Meistersinger, and of Parsifal cannot be held responsible for what his heirs and adherents made of his work. Would that it were so simple! Admittedly, there are good reasons to believe, with Thomas Mann, that the Dresden Kapellmeister and the anarchist revolutionary of 1848/49, had he lived to see it, would have opposed National Socialism and gone into exile, as Mann himself did in 1933. Mann left Germany because, ironically, he was viciously attacked for having besmirched the reputation of the composer, the supreme cultural icon of the opponents of the Weimar Republic on the Right and, as luck would have it, the idol of the Führer. But it cannot be denied that the nationalist and racist spin put on Parsifal is not entirely delusional and that such an interpretation was advanced well before 1933. Wagner’s “last card,” as he jokingly described it, does indeed contain a number of mystifying elements which, with a little bending of the evidence, do lend themselves to ideology-driven appropriation, especially given his many vehement pronouncements about both Germans and Jews. -

Assenet Inlays Cycle Ring Wagner OE

OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 1 An Introduction to... OPERAEXPLAINED WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson 2 CDs 8.558184–85 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 2 An Introduction to... WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson CD 1 1 Introduction 1:11 2 The Stuff of Legends 6:29 3 Dark Power? 4:38 4 Revolution in Music 2:57 5 A New Kind of Song 6:45 6 The Role of the Orchestra 7:11 7 The Leitmotif 5:12 Das Rheingold 8 Prelude 4:29 9 Scene 1 4:43 10 Scene 2 6:20 11 Scene 3 4:09 12 Scene 4 8:42 2 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 3 Die Walküre 13 Background 0:58 14 Act I 10:54 15 Act II 4:48 TT 79:34 CD 2 1 Act II cont. 3:37 2 Act III 3:53 3 The Final Scene: Wotan and Brünnhilde 6:51 Siegfried 4 Act I 9:05 5 Act II 7:25 6 Act III 12:16 Götterdämmerung 7 Background 2:05 8 Prologue 8:04 9 Act I 5:39 10 Act II 4:58 11 Act III 4:27 12 The Final Scene: The End of Everything? 11:09 TT 79:35 3 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 4 Music taken from: Das Rheingold – 8.660170–71 Wotan ...............................................................Wolfgang Probst Froh...............................................................Bernhard Schneider Donner ....................................................................Motti Kastón Loge........................................................................Robert Künzli Fricka...............................................................Michaela -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

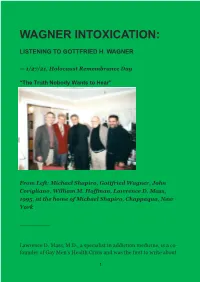

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

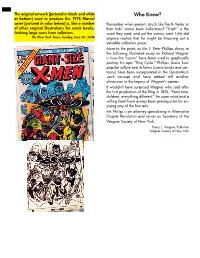

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Ebook Download Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around

WAGNERS RING TURNING THE SKY AROUND - AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RING OF THE NIBELUNG 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M Owen Lee | 9780879101862 | | | | | Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around - An Introduction to the Ring of the Nibelung 1st edition PDF Book It is even possible for the orchestra to convey ideas that are hidden from the characters themselves—an idea that later found its way into film scores. Unfamiliarity with Wagner constitutes an ignorance of, well, Wagnerian proportions. Some of my friends have seen far more than these. This section does not cite any sources. Digital watches chime the hour in half-diminished seventh chords. The daughters of the Rhine come up and pull Hagen into the depth of the Rhine. The plot synopses were helpful, but some of the deep psychological analysis was a bit boring. Next he encounters Wotan his grandfather , quarrels with him and cuts Wotan's staff of power in half. The next possessor of the ring, the giant Fafner, consumed with greed and lust for power, kills his brother, Fasolt, taking the spoils to the deep forest while the gods enter Valhalla to some of the most glorious and ironically triumphant music imaginable. Has underlining on pages. John shares his recipe for Nectar of the Gods. April Learn how and when to remove this template message. It's actually OK because that's what Wotan decreed for her anyway: First one up there shall have you. See Article History. Politics and music often go together. It left me at a whole new level of self-awareness, and has for all the years that have followed given me pleasures and insights that have enriched my life. -

From Page to Stage: Wagner As Regisseur

Wagner Ia 5/27/09 3:55 PM Page 3 Copyrighted Material From Page to Stage: Wagner as Regisseur KATHERINE SYER Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to pro- duction matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flour- ished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage produc- tion in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increas- ingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production. -

Read Book Wagner on Conducting

WAGNER ON CONDUCTING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Wagner,Edward Dannreuther | 118 pages | 01 Mar 1989 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486259321 | English | New York, United States Richard Wagner | Biography, Compositions, Operas, & Facts | Britannica Impulsive and self-willed, he was a negligent scholar at the Kreuzschule, Dresden , and the Nicholaischule, Leipzig. He frequented concerts, however, taught himself the piano and composition , and read the plays of Shakespeare, Goethe, and Schiller. Wagner, attracted by the glamour of student life, enrolled at Leipzig University , but as an adjunct with inferior privileges, since he had not completed his preparatory schooling. Although he lived wildly, he applied himself earnestly to composition. Because of his impatience with all academic techniques, he spent a mere six months acquiring a groundwork with Theodor Weinlig, cantor of the Thomasschule; but his real schooling was a close personal study of the scores of the masters, notably the quartets and symphonies of Beethoven. He failed to get the opera produced at Leipzig and became conductor to a provincial theatrical troupe from Magdeburg , having fallen in love with one of the actresses of the troupe, Wilhelmine Minna Planer, whom he married in In , fleeing from his creditors, he decided to put into operation his long-cherished plan to win renown in Paris, but his three years in Paris were calamitous. Living with a colony of poor German artists, he staved off starvation by means of musical journalism and hackwork. In , aged 29, he gladly returned to Dresden, where Rienzi was triumphantly performed on October The next year The Flying Dutchman produced at Dresden, January 2, was less successful, since the audience expected a work in the French-Italian tradition similar to Rienzi and was puzzled by the innovative way the new opera integrated the music with the dramatic content. -

Was Hitler a Darwinian?

Was Hitler a Darwinian? Robert J. Richards The University of Chicago The Darwinian underpinnings of Nazi racial ideology are patently obvious. Hitler's chapter on "Nation and Race" in Mein Kampf discusses the racial struggle for existence in clear Darwinian terms. Richard Weikart, Historian, Cal. State, Stanislaus1 Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that's almost in shape of a camel? Shakespeare, Hamlet, III, 2. 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Issues regarding a Supposed Conceptually Causal Connection . 4 3. Darwinian Theory and Racial Hierarchy . 10 4. The Racial Ideology of Gobineau and Chamberlain . 16 5. Chamberlain and Hitler . 27 6. Mein Kampf . 29 7. Struggle for Existence . 37 8. The Political Sources of Hitler’s Anti-Semitism . 41 9. Ethics and Social Darwinism . 44 10. Was the Biological Community under Hitler Darwinian? . 46 11. Conclusion . 52 1. Introduction Several scholars and many religiously conservative thinkers have recently charged that Hitler’s ideas about race and racial struggle derived from the theories of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), either directly or through intermediate sources. So, for example, the historian Richard Weikart, in his book From Darwin to Hitler (2004), maintains: “No matter how crooked the road was from Darwin to Hitler, clearly Darwinism and eugenics smoothed the path for Nazi ideology, especially for the Nazi 1 Richard Weikart, “Was It Immoral for "Expelled" to Connect Darwinism and Nazi Racism?” (http://www.discovery.org/a/5069.) 1 stress on expansion, war, racial struggle, and racial extermination.”2 In a subsequent book, Hitler’s Ethic: The Nazi Pursuit of Evolutionary Progress (2009), Weikart argues that Darwin’s “evolutionary ethics drove him [Hitler] to engage in behavior that the rest of us consider abominable.”3 Other critics have also attempted to forge a strong link between Darwin’s theory and Hitler’s biological notions. -

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan Und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding)

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding) Background information and performance circumstances Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was the greatest exponent of mid-nineteenth-century German romanticism. Like some other leading nineteenth-century musicians, but unlike those from previous eras, he was never a professional instrumentalist or singer, but worked as a freelance composer and conductor. A genius of over-riding force and ambition, he created a new genre of ‘music drama’ and greatly expanded the expressive possibilities of tonal composition. His works divided musical opinion, and strongly influenced several generations of composers across Europe. Career Brought up in a family with wide and somewhat Bohemian artistic connections, Wagner was discouraged by his mother from studying music, and at first was drawn more to literature – a source of inspiration he shared with many other romantic composers. It was only at the age of 15 that he began a secret study of harmony, working from a German translation of Logier’s School of Thoroughbass. [A reprint of this book is available on the Internet - http://archive.org/details/logierscomprehen00logi. The approach to basic harmony, remarkably, is very much the same as we use today.] Eventually he took private composition lessons, completing four years of study in 1832. Meanwhile his impatience with formal training and his obsessive attention to what interested him led to a succession of disasters over his education in Leipzig, successively at St Nicholas’ School, St Thomas’ School (where Bach had been cantor), and the university. At the age of 15, Wagner had written a full-length tragedy, and in 1832 he wrote the libretto to his first opera.