The Effect of Richard Wagner's Music and Beliefs on Hitler's Ideology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23Rd to 27Th September 2020

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23rd to 27th September 2020 Imprint The Richard Wagner Congress 2020 Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn e.V. programme Andreas Loesch (Vorsitzender) John Peter (stellv. Vorsitzender) was created in collaboration with Zanderstraße 47, 53177 Bonn Tel. +49-(0)178-8539559 [email protected] Organiser / booking details ARS MUSICA Musik- und Kulturreisen GmbH Bachemer Straße 209, 50935 Köln Tel: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 00 Fax: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 01 [email protected] RICHARD-WAGNER-VERBAND BONN E.V. and is sponsored by Image sources frontpage from left to right, from top to bottom - Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Deutsche Post / Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - StadtMuseum Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Beethovenhaus Bonn - Stadt Königswinter - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Stadtmuseum Siegburg - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn Current information about the program backpage - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn rwv-bonn.de/kongress-2020 Congress Programme for all Congress days 2 p.m. | Gustav-Stresemann-Institut Dear Members of the Richard Wagner Societies, dear Friends of Richard Wagner’s Music, Conference Hotel Hilton Richard Wagner – en miniature Symposium: »Beethoven, Wagner and the political “Welcome” to the Congress of the International Association of Richard Wagner Societies in 2020, commemorating Ludwig “Der Meister” depicted on stamps movements of their time « (simultaneous translation) van Beethoven’s 250th birthday worldwide. Richard Wagner appreciated him more than any other composer in his life, which Prof. Dr. Dieter Borchmeyer, PD Dr. Ulrike Kienzle, is why the Congress in Bonn, Beethoven’s hometown, is going to centre on “Beethoven and Wagner”. -

“Durch Mitleid Wissend”

“Durch Mitleid wissend” William Kinderman. Wagner’s Parsifal. Oxford University Press, New York, ©2013. 336.p., illus., 93 music examples. [This review first appeared in the December 2013 issue of Wagner Notes and appears here with permission of the author and of the Wagner Society of New York.] Most Wagnerians, amateurs and professionals alike, are sick and tired of being reminded of the darkly embarrassing links that connect their hero to Adolf Hitler. For many, the very name of the German dictator constitutes a disquieting irritant that thoroughly spoils their appreciation of Wagner’s music dramas. They argue, not without reason, that the creator of the Ring tetralogy, of Die Meistersinger, and of Parsifal cannot be held responsible for what his heirs and adherents made of his work. Would that it were so simple! Admittedly, there are good reasons to believe, with Thomas Mann, that the Dresden Kapellmeister and the anarchist revolutionary of 1848/49, had he lived to see it, would have opposed National Socialism and gone into exile, as Mann himself did in 1933. Mann left Germany because, ironically, he was viciously attacked for having besmirched the reputation of the composer, the supreme cultural icon of the opponents of the Weimar Republic on the Right and, as luck would have it, the idol of the Führer. But it cannot be denied that the nationalist and racist spin put on Parsifal is not entirely delusional and that such an interpretation was advanced well before 1933. Wagner’s “last card,” as he jokingly described it, does indeed contain a number of mystifying elements which, with a little bending of the evidence, do lend themselves to ideology-driven appropriation, especially given his many vehement pronouncements about both Germans and Jews. -

Wagner and Bayreuth Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Brahms and Detmold

MUSIC DOCUMENTARY 30 MIN. VERSIONS Wagner and Bayreuth Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) No city in the world is so closely identified with a composer as Bayreuth is with Richard Wag- ner. Towards the end of the 19th century Richard Wagner had a Festival Theatre built here and RIGHTS revived the Ancient Greek idea of annual festivals. Nowadays, these festivals are attended by Worldwide, VOD, Mobile around 60,000 people. ORDER NUMBER 66 3238 VERSIONS Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Felix Mendelssohn, one of the most important composers of the 19th century, was influenced decisively by Berlin, which gave shape to the form and development of his music. The televi- RIGHTS sion documentary traces Mendelssohn’s life in the Berlin of the 19th century, as well as show- Worldwide, VOD, Mobile ing the city today. ORDER NUMBER 66 3305 VERSIONS Brahms and Detmold Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Around the middle of the 19th century Detmold, a small town in the west of Germany, was a centre of the sort of cultural activity that would normally be expected only of a large city. An RIGHTS artistically-minded local prince saw to it that famous artists came to Detmold and performed in Worldwide, VOD, Mobile the theatre or at his court. For several years the town was the home of composer Johannes Brahms. Here, as Court Musician, he composed some of his most beautiful vocal and instru- ORDER NUMBER ment works. 66 3237 dw-transtel.com Classics | DW Transtel. -

Reviving Hitler's Favorite Music

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 9, Number 35, September 14, 1982 Reviving Hitler's favorite music In Seattle, the Weyerhaeuserfamily is promoting Wagner's Ring cycle as a wedgefor the "new dark age" within the U.S. , writes Mark Calney If you want to see true Wagner you must go to Seattle. greeted not by the presence of our local Northwestpatricians -Winifred Wagner in black tie, which one would expect during the German cycle, but rather the flannel shirt and denim set. There were It was precisely 106 years ago in the ancient Bavarian forest cowboys from Colorado, gays from San Francisco, the on the outskirts of the German village of Bayreuth, that the neighborhood Anglican priest, and what appeared to be the first complete cycle of Richard Wagner's The Ring of the entire anthropology department from the local university, Nibelungs was performed. It was a most regal affair. This dispersed among the crowd. I overheard conversations in was to be the unveiling of mankind's greatest artistic achieve Japanese, German, Spanish, and Texan. A number of these ment, a four-day epic opera concerning the mythical birth pilgrims came from around the world-from Switzerland, and destiny of Man, depicting his various struggles amidst a South Africa, Tasmania, Chile, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia flotsamof dragons, dwarfs, and gods. Who was to attend this from 25 different countriesand from every state in the union. festival heralding the "New Age" in Wagner's "democratic For some it was their eighth sojournto this idyllically under theater?" populated part of America, to participate in the revelries of The premier day of Das Rheingold found the Bayreuth the only festival in the world which contiguously performs theater stuffed to the rafters with every imaginable repre the German and English cycles of the Ring (14 days), and sentative of the European oligarchy from Genoa to St. -

05-09-2019 Siegfried Eve.Indd

Synopsis Act I Mythical times. In his cave in the forest, the dwarf Mime forges a sword for his foster son Siegfried. He hates Siegfried but hopes that the youth will kill the dragon Fafner, who guards the Nibelungs’ treasure, so that Mime can take the all-powerful ring from him. Siegfried arrives and smashes the new sword, raging at Mime’s incompetence. Having realized that he can’t be the dwarf’s son, as there is no physical resemblance between them, he demands to know who his parents were. For the first time, Mime tells Siegfried how he found his mother, Sieglinde, in the woods, who died giving birth to him. When he shows Siegfried the fragments of his father’s sword, Nothung, Siegfried orders Mime to repair it for him and storms out. As Mime sinks down in despair, a stranger enters. It is Wotan, lord of the gods, in human disguise as the Wanderer. He challenges the fearful Mime to a riddle competition, in which the loser forfeits his head. The Wanderer easily answers Mime’s three questions about the Nibelungs, the giants, and the gods. Mime, in turn, knows the answers to the traveler’s first two questions but gives up in terror when asked who will repair the sword Nothung. The Wanderer admonishes Mime for inquiring about faraway matters when he knows nothing about what closely concerns him. Then he departs, leaving the dwarf’s head to “him who knows no fear” and who will re-forge the magic blade. When Siegfried returns demanding his father’s sword, Mime tells him that he can’t repair it. -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

Beyond the Racial State

Beyond the Racial State Rethinking Nazi Germany Edited by DEVIN 0. PENDAS Boston College MARK ROSEMAN Indiana University and · RICHARD F. WETZELL German Historical Institute Washington, D.C. GERMAN lflSTORICAL INSTITUTE Washington, D.C. and CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS I Racial Discourse, Nazi Violence, and the Limits of the Racial State Model Mark Roseman It seems obvious that the Nazi regime was a racial state. The Nazis spoke a great deal about racial purity and racial difference. They identified racial enemies and murdered them. They devoted considerable attention to the health of their own "race," offering significant incentives for marriage and reproduction of desirable Aryans, and eliminating undesirable groups. While some forms of population eugenics were common in the interwar period, the sheer range of Nazi initiatives, coupled with the Nazis' willing ness to kill citizens they deemed physically or mentally substandard, was unique. "Racial state" seems not only a powerful shorthand for a regime that prioritized racial-biological imperatives but also above all a pithy and plausible explanatory model, establishing a strong causal link between racial thinking, on the one hand, and murderous population policy and genocide, on the other. There is nothing wrong with attaching "racial. state" as a descriptive label tci the Nazi regime. It successfully connotes a regime that both spoke a great deal about race and acted in the name of race. It enables us to see the links between a broad set of different population measures, some positively discriminatory, some murderously eliminatory. It reminds us how sttongly the Nazis believed that maximizing national power depended on managing the health and quality of the population. -

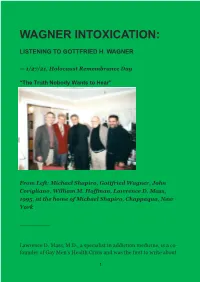

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

The Concept of Bildung in Early German Romanticism

CHAPTER 6 The Concept of Bildung in Early German Romanticism 1. Social and Political Context In 1799 Friedrich Schlegel, the ringleader of the early romantic circle, stated, with uncommon and uncharacteristic clarity, his view of the summum bonum, the supreme value in life: “The highest good, and [the source of] ev- erything that is useful, is culture (Bildung).”1 Since the German word Bildung is virtually synonymous with education, Schlegel might as well have said that the highest good is education. That aphorism, and others like it, leave no doubt about the importance of education for the early German romantics. It is no exaggeration to say that Bildung, the education of humanity, was the central goal, the highest aspiration, of the early romantics. All the leading figures of that charmed circle—Friedrich and August Wilhelm Schlegel, W. D. Wackenroder, Friedrich von Hardenberg (Novalis), F. W. J. Schelling, Ludwig Tieck, and F. D. Schleiermacher—saw in education their hope for the redemption of humanity. The aim of their common journal, the Athenäum, was to unite all their efforts for the sake of one single overriding goal: Bildung.2 The importance, and indeed urgency, of Bildung in the early romantic agenda is comprehensible only in its social and political context. The young romantics were writing in the 1790s, the decade of the cataclysmic changes wrought by the Revolution in France. Like so many of their generation, the romantics were initially very enthusiastic about the Revolution. Tieck, Novalis, Schleiermacher, Schelling, Hölderlin, and Friedrich Schlegel cele- brated the storming of the Bastille as the dawn of a new age. -

The Impact of the Third Reich on Famous Composers by Bwaar Omer

The Impact of the Third Reich on Famous Composers By Bwaar Omer Germany is known as a land of poets and thinkers and has been the origin of many great composers and artists. In the early 1920s, the country was becoming a hub for artists and new music. In the time of the Weimar Republic during the roaring twenties, jazz music was a symbol of the time and it was used to represent the acceptance of the newly introduced cultures. Many conservatives, however, opposed this rise of for- eign culture and new music. Guido Fackler, a German scientist, contends this became a more apparent issue when Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) took power in 1933 and created the Third Reich. The forbidden music during the Third Reich, known as degen- erative music, was deemed to be anti-German and people who listened to it were not considered true Germans by nationalists. A famous composer who was negatively affected by the brand of degenerative music was Kurt Weill (1900-1950). Weill was a Jewish composer and playwright who was using his com- positions and stories in order to expose the Nazi agenda and criticize society for not foreseeing the perils to come (Hinton par. 11). Weill was exiled from Germany when the Nazi party took power and he went to America to continue his career. While Weill was exiled from Germany and lacked power to fight back, the Nazis created propaganda to attack any type of music associated with Jews and blacks. The “Entartete Musik” poster portrays a cartoon of a black individual playing a saxo- phone whose lips have been enlarged in an attempt to make him look more like an animal rather than a human.