A Visit to Australia's Opal Fields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulse March 2020

South West Hospital and Health Service Getting ready for Harmony Week 2020 from Cunnamulla were (clockwise from left) Tina Jackson, Deirdre Williams, Kylie McKellar, Jonathan Mullins, Rachel Hammond Please note: This photo was taken before implementation of social distancing measures. PULSE MARCH 2020 EDITION From the Board Chair Jim McGowan AM 5 From the Chief Executive, Linda Patat 6 OUR COMMUNITIES All in this together - COVID-19 7 Roma CAN supports the local community in the fight against COVID-19 10 Flood waters won’t stop us 11 Everybody belongs, Harmony Week celebrated across the South West 12 Close the Gap, our health, our voice, our choice 13 HOPE supports Adrian Vowles Cup 14 Voices of the lived experience part of mental health forum 15 Taking a stand against domestic violence 16 Elder Annie Collins celebrates a special milestone 17 Shaving success in Mitchell 17 Teaching our kids about good hygiene 18 Students learn about healthy lunch boxes at Injune State School 18 OUR TEAMS Stay Connected across the South West 19 Let’s get physical, be active, be healthy 20 Quilpie staff loving the South West 21 Don’t forget to get the ‘flu’ shot 22 Sustainable development goals 24 Protecting and promoting Human Rights 25 Preceptor program triumphs in the South West 26 Practical Obstetric Multi Professional Training (PROMPT) workshop goes virtual 27 OUR SERVICES Paving the way for the next generation of rural health professionals 28 A focus on our ‘Frail Older Persons’ 29 South West Cardiac Services going from strength to strength 30 WQ Pathways Live! 30 SOUTH WEST SPIRIT AWARD 31 ROMA HOSPITAL BUILD UPDATE 32 We would like to pay our respects to the traditional owners of the lands across the South West. -

EARLY COOBER PEDY SHOW HOME/DUGOUT - for SALE Coober Pedy Is a Town Steeped in the Rich History of Early Opal Mining and Its Related Industry Tourism

ISSN 1833-1831 Tel: 08 8672 5920 http://cooberpedyregionaltimes.wordpress.com Thursday 19 May 2016 EARLY COOBER PEDY SHOW HOME/DUGOUT - FOR SALE Coober Pedy is a town steeped in the rich history of early opal mining and its related industry tourism. The buying and selling of dugouts is a way of life in the Opal Capital of the World where the majority of family homes are subterranean. A strong real-estate presence has always been evident in Coober Pedy, but opal mining family John and Jerlyn Nathan with their two daughters are self-selling their historic dugout in order to buy an acreage just out of town that will suit their growing family’s needs better. The Nathan family currently live on the edge of town, a few minutes from the school and not far from the shops. Despite they brag one of most historic homes around with a position and a view from the east side of North West Ridge to be envied, John tells us that his growing family needs more space outside. “Prospector’s Dugout has plenty of space inside, with 4 bedrooms plus,” said John. “But the girls have grown in 5 years and we have an opportunity, once this property is sold, to buy an acreage outside of town, and where my daughters can have a trail bike and other outdoor activities where it won’t bother anyone.” “I will regret relinquishing our location and view but I think kids need the freedom of the outdoors when they are growing up,’ he said. John and Jeryln bought the 1920’s dugout at 720 Russell John and Jerlyn Nathan with daughters De’ Arna and Darna on the patio at Prospector’s Dugout. -

Melanie-Hava-Bio-1

Melanie Hava Aboriginal name: "Winden" - green pigeon I am blessed to have been born into interesting and diverse cultures: my father comes from the oldest city in Austria, Enns (Upper Austria) and my mother is from one of the oldest cultures in the world, Aboriginal people of Australia. While celebrating my Austrian heritage, I also identify through my Mum's line as a Mamu Aboriginal woman, Dugul-barra and Wari-barra family groups, from the Johnstone River catchment of the Wet Tropics of Far North Queensland and the adjoining Great Barrier Reef sea country. Reef and rainforest country are important sources for my inspirations. I have known from a very young age that I was going to be an artist. While also being a bookworm and a piano player, art was a world that I frequently retreated into as I grew up. I reckon this is because I was deaf and felt I couldn't join in with groups of people. As a teen and along with my sister Joelene, we created art on didgeridoos and canvas. This art sold very quickly in the little, opal mining outback town of Yowah way out back of western Queensland. This red soil country still influences my works. When I was in my late teens/early twenties, I started playing around with the ideas of combining my Aboriginal and Austrian inspirations. I had already tried my style in Aboriginal, Folk and Abstract arts and I had had a successful first exhibition at Outback at Isa Gallery. So at 23 I travelled to Austria to live with my father's family and absorb as much as I could of the Folk and European culture. -

Walgett Shire

Walgett Shire WALGETT SHIRE FLOOD EMERGENCY SUB PLAN A Sub-Plan of the Walgett Shire Council Local Emergency Management Plan (EMPLAN) Volume 1 of the Walgett Shire Local Flood Plan Walgett Shire Local Flood Plan AUTHORISATION The Walgett Shire Flood Emergency Sub Plan is a sub plan of the Walgett Shire Local Emergency Management Plan (EMPLAN). It has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the State Emergency Service Act 1989 (NSW) and is authorised by the Local Emergency Management Committee in accordance with the provisions of the State Emergency and Rescue Management Act 1989 (NSW). August 2013 Walgett Shire Flood Emergency Sub Plan Page i Walgett Shire Local Flood Plan CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................................... ii DISTRIBUTION LIST ......................................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................. vi GLOSSARY ..................................................................................................................................................... viii PART 1 - INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................................. -

Safety in Opal Mining Guide

Safety in Opal Mining Opal Miner’s Guide Coober Pedy Mine Rescue emergency phone number is 8672 5999. Andamooka Mine Rescue emergency phone numbers are (Police) 8672 7072, (Clinic) 8672 7087, (Post office) 8672 7007. Mintabie Mine Rescue emergency phone numbers are (clinic) 8670 5032, (SES) 8670 5162, 8670 5037 A.H. South Australia Opal Fields Disclaimer Information provided in this publication is designed to address the most commonly raised issues in the workplace relevant to South Australian legislation such as the Occupational Health Safety and Welfare Act 1986 and the Workers Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1986. They are not intended as a replacement for the legislation. In particular, WorkCover Corporation, its agents, officers and employees : • make no representations, express or implied, as to the accuracy of the information and data contained in the publication, • accept no liability for any use of the said information or reliance placed on it, and make no representations, either expressed or implied, as to the suitability of the said information for any particular purpose. Awards recognition 1999 S.A Resources Industry Awards. Judges Citation for Safety Culture Development Awarded to Safety in Opal Mining Project. ISBN: 0 9585938 5 X Cover: Opals. Black Opals Majestic Opals Safety in Opal Mining Opal miner’s guide A South Australian Project. Funded by: The Mining and Quarrying Occupational Health and Safety Committee. Project Officer: Sophia Provatidis. With input from the miners of Coober Pedy, Mintabie, Andamooka and Lambina. -

Coober Pedy, South Australia

The etymology of Coober Pedy, South Australia Petter Naessan The aim of this paper is to outline and assess the diverging etymologies of ‘Coober Pedy’ in northern South Australia, in the search for original and post-contact local Indigenous significance associated with the name and the region. At the interface of contemporary Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara opinion (mainly in the Coober Pedy region, where I have conducted fieldwork since 1999) and other sources, an interesting picture emerges: in the current use by Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people as well as non-Indigenous people in Coober Pedy, the name ‘Coober Pedy’ – as ‘white man’s hole (in the ground)’ – does not seem to reflect or point toward a pre-contact Indigenous presence. Coober Pedy is an opal mining and tourist town with a total population of about 3500, situated near the Stuart Highway, about 850 kilometres north of Adelaide, South Australia. Coober Pedy is close to the Stuart Range, lies within the Arckaringa Basin and is near the border of the Great Victoria Desert. Low spinifex grasslands amounts for most of the sparse vegetation. The Coober Pedy and Oodnadatta region is characterised by dwarf shrubland and tussock grassland. Further north and northwest, low open shrub savanna and open shrub woodland dominates.1 Coober Pedy and surrounding regions are arid and exhibit very unpredictable rainfall. Much of the economic activity in the region (as well as the initial settlement of Euro-Australian invaders) is directly related to the geology, namely quite large deposits of opal. The area was only settled by non-Indigenous people after 1915 when opal was uncovered but traditionally the Indigenous population was western Arabana (Midlaliri). -

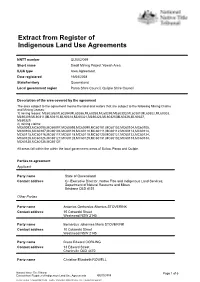

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements NNTT number QI2002/059 Short name Small Mining Project Yowah Area ILUA type Area Agreement Date registered 16/04/2004 State/territory Queensland Local government region Paroo Shire Council, Quilpie Shire Council Description of the area covered by the agreement The area subject to the agreement means the land and waters that are subject to the following Mining Claims and Mining Leases: 1) mining leases: ML60289,ML60294,ML60296,ML60298,ML60299,ML60300,ML60301,ML60302,ML60303, ML60309,ML60311,ML60315,ML60318,ML60321,ML60323,ML60325,ML60326,ML60327, ML60329. 2) mining claims: MC60093,MC60095,MC60097,MC60098,MC60099,MC60101,MC60102,MC60104,MC60105, MC60106,MC60107,MC60108,MC60109,MC60110,MC60111,MC60112,MC60113,MC60114, MC60115,MC60116,MC60117,MC60118,MC60119,MC60120,MC60121,MC60122,MC60124, MC60125,MC60126,MC60127,MC60128,MC60129,MC60131,MC60132,MC60133,MC60134, MC60135,MC60136,MC60137. All areas fall within the within the local government areas of Bulloo, Paroo and Quilpie. Parties to agreement Applicant Party name State of Queensland Contact address C/- Executive Director, Native Title and Indigenous Land Services, Department of Natural Resource and Mines Brisbane QLD 4151 Other Parties Party name Antonius Gerhardus Albertus STOVERINK Contact address 10 Cotswold Street Westmead NSW 2145 Party name Bernardus Johannes Maria STOVERINK Contact address 10 Cotswold Street Westmead NSW 2145 Party name Bruce Edward CORLING Contact address 13 Edward Street Charleville QLD 4470 Party name Christine -

Outback NSW Regional

TO QUILPIE 485km, A THARGOMINDAH 289km B C D E TO CUNNAMULLA 136km F TO CUNNAMULLA 75km G H I J TO ST GEORGE 44km K Source: © DEPARTMENT OF LANDS Nindigully PANORAMA AVENUE BATHURST 2795 29º00'S Olive Downs 141º00'E 142º00'E www.lands.nsw.gov.au 143º00'E 144º00'E 145º00'E 146º00'E 147º00'E 148º00'E 149º00'E 85 Campground MITCHELL Cameron 61 © Copyright LANDS & Cartoscope Pty Ltd Corner CURRAWINYA Bungunya NAT PK Talwood Dog Fence Dirranbandi (locality) STURT NAT PK Dunwinnie (locality) 0 20 40 60 Boonangar Hungerford Daymar Crossing 405km BRISBANE Kilometres Thallon 75 New QUEENSLAND TO 48km, GOONDIWINDI 80 (locality) 1 Waka England Barringun CULGOA Kunopia 1 Region (locality) FLOODPLAIN 66 NAT PK Boomi Index to adjoining Map Jobs Gate Lake 44 Cartoscope maps Dead Horse 38 Hebel Bokhara Gully Campground CULGOA 19 Tibooburra NAT PK Caloona (locality) 74 Outback Mungindi Dolgelly Mount Wood NSW Map Dubbo River Goodooga Angledool (locality) Bore CORNER 54 Campground Neeworra LEDKNAPPER 40 COUNTRY Region NEW SOUTH WALES (locality) Enngonia NAT RES Weilmoringle STORE Riverina Map 96 Bengerang Check at store for River 122 supply of fuel Region Garah 106 Mungunyah Gundabloui Map (locality) Crossing 44 Milparinka (locality) Fordetail VISIT HISTORIC see Map 11 elec 181 Wanaaring Lednapper Moppin MILPARINKA Lightning Ridge (locality) 79 Crossing Coocoran 103km (locality) 74 Lake 7 Lightning Ridge 30º00'S 76 (locality) Ashley 97 Bore Bath Collymongle 133 TO GOONDIWINDI Birrie (locality) 2 Collerina NARRAN Collarenebri Bullarah 2 (locality) LAKE 36 NOCOLECHE (locality) Salt 71 NAT RES 9 150º00'E NAT RES Pokataroo 38 Lake GWYDIR HWY Grave of 52 MOREE Eliza Kennedy Unsealed roads on 194 (locality) Cumborah 61 Poison Gate Telleraga this map can be difficult (locality) 120km Pincally in wet conditions HWY 82 46 Merrywinebone Swamp 29 Largest Grain (locality) Hollow TO INVERELL 37 98 For detail Silo in Sth. -

Corporate Plan 2018 - 2023

CORPORATE PLAN 2018 - 2023 REVIEWED 30 JUNE 2020 - 19 CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR AND CEO 4 PAROO SHIRE COUNCILLORS 5 ABOUT PAROO SHIRE 6 KEY STATISTICS 7 ABOUT THE CORPORATE PLAN 9 COMMUNITY CONSULTATION PROCESS 10 OUR VISION, MISSION AND VALUES 11 MONITORING OUR PROGRESS 11 COUNCIL’S ROLE 11 OUR PRIORITIES FOR 2018 - 2023 12 - 13 PROGRAMS AND SERVICES 14 - 19 Photo credit (bottom image on front cover): Footprints in Mud by M Johnstone 2019 #ParooPride Photography Competition Adult Runner-up 2 PAROO SHIRE COUNCIL 2018 - 2023 CORPORATE PLAN 3 MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR AND CEO We look forward to the coming year as Paroo Shire comes out of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and starts to rebuild its visitor numbers which in turn will re-energise our local businesses. This year is the mid point of our Corporate Plan and a number of our priorities have been achieved, particularly our aim to obtain funding for major infrastructure works. A number of these projects will reach completion this year and will add to the long term sustainability of the Shire. Our staff are at the forefront of service delivery to the community and we extend our appreciation for their efforts and contribution to the organisation. Cr Suzette Beresford Sean Rice Mayor, Paroo Shire Acting CEO, Paroo Shire Council 4 PAROO SHIRE COUNCIL PAROO SHIRE COUNCILLORS Mayor, Cr Suzette Beresford 0427 551 191 [email protected] Deputy Mayor, Cr Rick Brain 0400 088 013 [email protected] Cr James Clark 0499 299 700 [email protected] Cr Patricia Jordan 0427 551 452 [email protected] Cr Joann Woodcroft 0427 551 230 [email protected] 2018 - 2023 CORPORATE PLAN 5 ABOUT PAROO SHIRE Paroo Shire is a rural region located in south west Queensland and includes the townships of Cunnamulla, Eulo, Wyandra and Yowah. -

Dimdimaapril2020.Pdf

2 In this issue: Comics Open House Stories 12 Boomslayer: The Mist 29 The Math Tutor 6 The Blackmailer 28 Secret Agent Zero 34 Vijay and the 36 The Wise Carpenter Anniversary Melon Plant 50 Haddiraj 23 50th Earth Day First & Foremost 32 Fastest Mammal Quest 26 Living Underground Fact-o-Meter 46 Q & A 42 Exotic Foods India File Nature Watch Movie Watch 44 The Ancient City of Lakes 24 My Winter Friend 29 Pawfect Entertainment Hall of Fame 9 Champion of the Curiosities Downtrodden 41 Book Bandit Bhavan’s Turning Point Dimdima Bring out the Winner in You 43 The Star Stroker April 2020 Vol. 4 Issue 11 PUBLISHED BY DR. A VENUGOPALAN, ON BEHALF OF Brain Power BHARATIYA VIDYA BHAVAN, 18, 20, EAST MADA STREET, MYLAPORE, CHENNAI-600 004 AND PRINTED BY 10 Teasers & Puzzles SHRI B. RAJ KUMAR AT RASI GRAPHICS, (P) LTD., NO. 40, PETERS ROAD, ROYAPETTAH, CHENNAI–600 014. 49 Word Whiz EDITOR: MAHUA GUHA 33 Poetry Nook CONSULTING EDITOR: MEERA NAIR ASSISTANT EDITOR: SHWETA MITTAL 45 It Happened to Me COPYRIGHTS: BHARATIYA VIDYA BHAVAN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THROUGHOUT THE WORLD. 47 Jokeshop EDITORIAL, CIRCULATION & DIMDIMA SUBSCRIPTION NEW DELHI OFFICE ADVERTISEMENTS Rs. 375/- for 12 issues. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Rs. 725/- for 24 issues. Mehta Sadan, K. G. Marg, Gora Gandhi Compound, Rs. 1050/- for 36 issues. New Delhi 110001 505, Sane Guruji Marg, Postage Free. Payment by MO or DD in favour Phone: 011-23381847 Tardeo, Mumbai 400034 of Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan payable at Mumbai. Phone: 022–23526025 & 23531991 Please include Rs.100/- extra if you want Email: [email protected] your copy to be sent by courier in Mumbai, CHENNAI OFFICE [email protected] Rs.200/- extra for outside Mumbai. -

A Prospector's Guide to Opal in the Yowah-Eromanga Area

October, 1967 QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT MINING JOURNAL 453 A PROSPECTOR'S GUIDE TO OPAL IN THE YOWAH-EROMANGA AREA By J. H. BROOKS, B.Sc., Supervising Geologist (Economic Geology), Geological Survey of Queensland. An inspection of the Little Wonder area, west of Ero- The original find is said to have been in the vicinity of the manga, and the Yowah area, west of Cunnamulla, was made existing Water claim at Whisky Flat. Production has come from 13th to 15th July, 1967, in company with Mr. W. J. from this area and particularly from its extension to the Page, Acting Mining Warden, Cunnamulla, and Mr. A. J. west known as "Evans lead". Opal has also been won from Saunders, Inspector of Mines. the old Southern Cross and Brandy Gully areas. White, The main opal mining activity in South Western Queens- grey, blue and colourless "potch" is of common occurrence land is currently centred on the two areas visited, although and black potch has also been found. Precious opal mostly information from various miners indicates that there has occurs in the form of matrix opal. Wood opal is not un- been some activity in recent years in the Karoit, Black Gate common but the cell structure is usually almost obliterated. and Duck Creek areas in the Cunnamulla district, in the Combinations of potch and precious opal with unusual Kyabra area, north-west of Eromanga, and in the Canaway patterns (picture stones) are, found and are in demand for Downs area, north of Quilpie. Two claims have also been making up into novelty settings. -

South West Queensland Floods March 2010

South West Queensland Floods March 2010 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Floodwaters inundate the township of Bollon. Photo supplied by Bill Speedy. 2. Floodwaters at the Autumnvale gauging station on the lower Bulloo River. Photo supplied by R.D. & C.B. Hughes. 3. Floodwaters from Bradley’s Gully travel through Charleville. 4. Floodwaters from Bungil Creek inundate Roma. Photo supplied by the Maranoa Regional Council. 5. Floodwaters at the confluence of the Paroo River and Beechal Creek. Photo supplied by Cherry and John Gardiner. 6. Balonne River floodwaters inundate low lying areas of St. George. Photo supplied by Sally Nichol. 7. Floodwaters from the Moonie River inundate Nindigully. Photo supplied by Sally Nichol. 8. Floodwaters from the Moonie River inundate the township of Thallon. Photo supplied by Sally Nichol. Revision history Date Version Description 6 June 2010 1.0 Original Original version of this report contained an incorrect date for the main flood peak at Roma. Corrected to 23 June 2010 1.1 8.1 metres on Tuesday 2 March 2010. See Table 3.1.1. An approximate peak height has been replaced for Bradley’s Gully at Charleville. New peak height is 4.2 28 June 2010 1.2 metres on Tuesday 2 March 2010 at 13:00. See Table 3.1.1. Peak height provided from flood mark at Teelba on 01 July 2010 1.3 Teelba Creek. See Table 3.1.1. 08 Spectember Peak height provided from flood mark at Garrabarra 1.4 2010 on Bungil Creek. See Table 3.1.1.