The Devil's Children: the Hatfield Lawyers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

WILLIAM WHITLEY 1749-1813 B¢ CHARLES G. TALBERT Part II* on a Small Rise Just South of U. S. Highway 150 and About Two Miles We

WILLIAM WHITLEY 1749-1813 B¢ CHARLES G. TALBERT Lexington, Kentucky Part II* THE WILLIAM WHITLEY HOUSE On a small rise just south of U. S. highway 150 and about two miles west of the town of Crab Orchard, Kentucky, stands the residence which was once the home of the pioneers, William and Esther Whitley. The house is of bricks, which are laid in Flemish bond rather than in one of the English bonds which are more common in Kentucky. In this type of construction each horizontal row of bricks contains alternating headers and stretch- ers, that is, one brick is laid lengthwise, the next endwise, etc. English bond may consist of alternating rows of headers and stretchers, or, as is more often the case, a row of headers every fifth, sixth, or seventh row.1 In the Whitley house the headers in the gable ends are glazed so that a slightly darker pattern, in this case a series of diamonds, stands out clearly. Thus is achieved the effect generally known as ornamental Flemish bond which dates back to eleventh cen- tury Normandy. One of the earliest known examples of this in England is a fourteenth century church at Ashington, Essex, and by the sixteenth century it was widely used for English dwellings.2 Another feature of the Whitley house which never fails to attract attention is the use of dark headers to form the initials of the owner just above the front entrance.3 The idea of brick initials and dates was known in England in the seventeenth cen- tury, one Herfordshire house bearing the inscription, "1648 W F M." One of the earliest American examples was Carthagena in St. -

Martin's Bench and Bar of Philadelphia

MARTIN'S BENCH AND BAR OF PHILADELPHIA Together with other Lists of persons appointed to Administer the Laws in the City and County of Philadelphia, and the Province and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania BY , JOHN HILL MARTIN OF THE PHILADELPHIA BAR OF C PHILADELPHIA KKKS WELSH & CO., PUBLISHERS No. 19 South Ninth Street 1883 Entered according to the Act of Congress, On the 12th day of March, in the year 1883, BY JOHN HILL MARTIN, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. W. H. PILE, PRINTER, No. 422 Walnut Street, Philadelphia. Stack Annex 5 PREFACE. IT has been no part of my intention in compiling these lists entitled "The Bench and Bar of Philadelphia," to give a history of the organization of the Courts, but merely names of Judges, with dates of their commissions; Lawyers and dates of their ad- mission, and lists of other persons connected with the administra- tion of the Laws in this City and County, and in the Province and Commonwealth. Some necessary information and notes have been added to a few of the lists. And in addition it may not be out of place here to state that Courts of Justice, in what is now the Com- monwealth of Pennsylvania, were first established by the Swedes, in 1642, at New Gottenburg, nowTinicum, by Governor John Printz, who was instructed to decide all controversies according to the laws, customs and usages of Sweden. What Courts he established and what the modes of procedure therein, can only be conjectur- ed by what subsequently occurred, and by the record of Upland Court. -

The County Courts in Antebellum Kentucky

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1972 The County Courts in Antebellum Kentucky Robert M. Ireland University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Ireland, Robert M., "The County Courts in Antebellum Kentucky" (1972). United States History. 65. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/65 This page intentionally left blank ROBERT M. IRELAND County Courts in Antebellum Kentucky The University Press of KentacRy ISBN 978-0-8131-531 1-7 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 71-160045 COPYRIGHT 0 1972 BY THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Kentucky State College, Morehead State University, Murray State Univer- sity, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Ofices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 The Anatomy of the County Courts 7 2 The Judicial Business of the County Courts 18 3 The Financial Business of the County Courts 35 4 The Politics of the County Courts 62 5 County Court Patronage 79 6 The County Courts and the Legislature 105 7 Town and Country 123 8 Deficiencies and Reform I45 Conclusion 171 Governors of Kentucky, 1792-1851 '77 Kentucky County Maps 178 An Essay on Authorities 181 Index 187 This page intentionally left blank Preface r IS PERHAPS IRONIC that some of the most outstanding work in pre-Civil War American historiography con- I cerns national political institutions which touched only lightly the daily lives of most citizens. -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

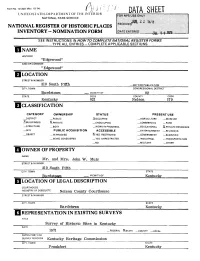

Data Sheet National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) f H ij / - ? • fr ^ • - s - UNITED STATES DHPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DATA SHEET NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC "Edgewood" AND/OR COMMON "Edgewood" STREET & NUMBER 310 South Fifth _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Bardstown —.VICINITY OF 02 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 Nelson 179 UCLA SSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT _ PUBLIC JKOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ZiBUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. and Mrs. John W. Muir STREET & NUMBER 310 South Fifth CITY. TOWN STATE Bardstown VICINITY OF Kentucky LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Nelson County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Kentucky REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Historic Sites in Kentucky DATE 1971 — FEDERAL X STATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Kentucky Heritage Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Frankfort Kentucky DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X.EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Ben Hardin House is a large brick structure located on a sizeable tract of land at the head of Fifth Street in Bardstown. The house consists of two distinct parts, erected at different periods. -

The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 11-15-1994 Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky" (1994). Appalachian Studies. 25. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/25 DAYS OF DARKNESS DAYS OF DARKNESS The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1994 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2010 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1 The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows: Pearce, John Ed. Days of darkness: the feuds of Eastern Kentucky / John Ed Pearce. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8131-1874-3 (hardcover: alk. -

University of Pennsylvania Catalogue, 1834

OF THE OFFICERS AND STUDENTS OF THE UN1YEBSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA. PHILADELPHIA: January, „1834. TRUSTEES THE GOVERNOR OF THE STATE, Ex Officio, President of the Board. RT. REV. WILLIAM WHITE, D. D. WILLIAM RAWLE, LL. D. BENJAMIN R. MORGAN, JAMES GIBSON, HORACE BINNEY, LL. D. WILLIAM MEREDITH, BENJAMIN CHEW, ROBERT WALN, JOHN SERGEANT, LL. D. THOMAS CADWALADER, PETER S. DUPONCEAU, LL. D. NICHOLAS BIDDLE, CHARLES CHAUNCEY, LL. D. JOSEPH HOPKINSON, LL. D. JOSEPH R. INGERSOLL, REY. PHILIP F. MAYER, D. D. PHILIP H. NICKLIN, RT. REY. HENRY U. ONDERDONK, D. D. JOHN C. LOWBER, JAMES S. SMITH, EDWARD S. BURD, JEROME KEATING, GEORGE VAUX, REV. WILLIAM H. DE LANCEY, D. D. JAMES C. BIDDLE, Secretary and Treasurer. REV. PHILIP LINDSLEY, D. D. PROVOST ELECT OF THE UNIVERSITY. ROBERT ADRAIN, LL. D. VICE PROVOST. FACULTY OF ARTS. REV. PHILIP LINDSLEY, D. D. Professor Elect Of Moral Philosophy. ROBERT ADRAIN, LL. D. Professor of Mathematics. REV. SAMUEL B. WYLIE, D. D. Professor of the Hebrew, Greek, and Latin Languages. ALEX. DALLAS BACHE, A. M. Professor of Natural Philosophy and Chemistry. HENRY REED, A. M. Assistant Professor of Moral Philosophy, having charge of the Department of English Literature, A. D. BACHE, Secretary of the Faculty. AUGUSTUS DE VALVILLE, Instructor in French. HERMANN BOKUM, Instructer in German. FREDERICK DICK, Janitor. ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT. REV. SAMUEL W. CRAWFORD, A. M. Principal and Teacher of Classics. THOMAS M'ADAM, Teacher of English. THEOPHILUS A. WYLIE, A. B. WILLIAM ALEXANDER, A. B. Assistants in the Classics. THOMAS M'ADAM, Jr. Assistant in the English School. FACULTY OF MEDICINE. PHILIP SYNG PHYSICK, M. -

In Nineteenth Century American Law Practice

St. Mary's Journal on Legal Malpractice & Ethics Volume 7 Number 2 Article 2 10-2017 Ethics and the “Root of All Evil” in Nineteenth Century American Law Practice Michael Hoeflich [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/lmej Part of the Law and Society Commons, Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Legal Studies Commons Recommended Citation Michael Hoeflich, Ethics and the “Root of All Evil” in Nineteenth Century American Law Practice, 7 ST. MARY'S JOURNAL ON LEGAL MALPRACTICE & ETHICS 160 (2017). Available at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/lmej/vol7/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the St. Mary's Law Journals at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Mary's Journal on Legal Malpractice & Ethics by an authorized editor of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE M.H. Hoeflich Ethics and the “Root of All Evil” in Nineteenth Century American Law Practice Abstract. This Article discusses the bifurcated notions on the purpose of working as an attorney—whether the purpose is to attain wealth or whether the work in and of itself is the purpose. This Article explores the sentiments held by distinguished and influential nineteenth-century lawyers—particularly David Hoffman and George Sharswood—regarding the legal ethics regarding attorney’s fees and how money in general is the root of many ethical dilemmas within the arena of legal practice. -

Rediscovering the Republican Origins of the Legal Ethics Codes

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 1992 Rediscovering the Republican Origins of the Legal Ethics Codes Russell G. Pearce Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Russell G. Pearce, Rediscovering the Republican Origins of the Legal Ethics Codes, 6 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 241 (1992-1993) Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/312 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rediscovering the Republican Origins of the Legal Ethics Codes RUSSELL G. PEARCE* I. INTRODUCTION The consensus among leading commentators on legal ethics issues is that the legal ethics codes' embody an adversarial ethic.2 An examination of the historical roots of the legal ethics codes in the work of George Sharswood, a nineteenth century jurist and scholar provides an alternative interpreta- tion.3 Although largely ignored by commentators today, Sharswood's essay 4 on ethics was the original source of most of the modern legal ethics codes. Sharswood believed that a lawyer's principal obligation was the republican pursuit of the community's common good even where it conflicts with ei- ther her client's or her own interests.5 Sharswood defined the common good as the protection of order, liberty, and property in order to provide individ- 6 uals with the opportunity to perfect themselves. -

Military History of Kentucky

THE AMERICAN GUIDE SERIES Military History of Kentucky CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED Written by Workers of the Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of Kentucky Sponsored by THE MILITARY DEPARTMENT OF KENTUCKY G. LEE McCLAIN, The Adjutant General Anna Virumque Cano - Virgil (I sing of arms and men) ILLUSTRATED Military History of Kentucky FIRST PUBLISHED IN JULY, 1939 WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION F. C. Harrington, Administrator Florence S. Kerr, Assistant Administrator Henry G. Alsberg, Director of The Federal Writers Project COPYRIGHT 1939 BY THE ADJUTANT GENERAL OF KENTUCKY PRINTED BY THE STATE JOURNAL FRANKFORT, KY. All rights are reserved, including the rights to reproduce this book a parts thereof in any form. ii Military History of Kentucky BRIG. GEN. G. LEE McCLAIN, KY. N. G. The Adjutant General iii Military History of Kentucky MAJOR JOSEPH M. KELLY, KY. N. G. Assistant Adjutant General, U.S. P. and D. O. iv Military History of Kentucky Foreword Frankfort, Kentucky, January 1, 1939. HIS EXCELLENCY, ALBERT BENJAMIN CHANDLER, Governor of Kentucky and Commander-in-Chief, Kentucky National Guard, Frankfort, Kentucky. SIR: I have the pleasure of submitting a report of the National Guard of Kentucky showing its origin, development and progress, chronologically arranged. This report is in the form of a history of the military units of Kentucky. The purpose of this Military History of Kentucky is to present a written record which always will be available to the people of Kentucky relating something of the accomplishments of Kentucky soldiers. It will be observed that from the time the first settlers came to our state, down to the present day, Kentucky soldiers have been ever ready to protect the lives, homes, and property of the citizens of the state with vigor and courage.