The County Courts in Antebellum Kentucky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indiana Magazine of History

INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY VOLUMEXXV DECEMBER, 1929 NUMBER4 The Burr Conspiracy In Indiana* By ISAACJ. Cox Indiana in the days of the Burr Conspiracy embraced a much larger area than today-at least technically. It extend- ed westward from the boundary of the recently-created state of Ohio to the Mississippi. The white settlements within this area were, it is true, few and scattering. The occasional clearings within the forests were almost wholly occupied by Indians slowly receding before the advance of a civilization that was too powerful for them. But sparse as was the popu- lation of the frontier territory when first created, its infini- tesimal average per square mile had been greatly lowered in 1804, for Congress had bestowed upon its governor the ad- ministration of that part of Louisiana that lay above the thirty-third parallel. As thus constituted, it was a region of boundless aspira- tions-a fitting stage for two distinguished travelers who journeyed through it the following year. Within its extended confines near the mouth of the Ohio lay Fort Massac, where in June, '1805, Burr held his mysterious interview with Wilkinson,' and also the cluster of French settlements from which William Morrison, the year before, had attempted to open trading relations with Santa Fe2-a project in which Wilkinson was to follow him. It was here that Willrinson, the second of this sinister pair, received from his predecessor a letter warning him against political factions in his new juris- diction.a By this act Governor Harrison emphasized not only his own personal experiences, but also the essential connection of the area with Hoosierdom. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

WILLIAM WHITLEY 1749-1813 B¢ CHARLES G. TALBERT Part II* on a Small Rise Just South of U. S. Highway 150 and About Two Miles We

WILLIAM WHITLEY 1749-1813 B¢ CHARLES G. TALBERT Lexington, Kentucky Part II* THE WILLIAM WHITLEY HOUSE On a small rise just south of U. S. highway 150 and about two miles west of the town of Crab Orchard, Kentucky, stands the residence which was once the home of the pioneers, William and Esther Whitley. The house is of bricks, which are laid in Flemish bond rather than in one of the English bonds which are more common in Kentucky. In this type of construction each horizontal row of bricks contains alternating headers and stretch- ers, that is, one brick is laid lengthwise, the next endwise, etc. English bond may consist of alternating rows of headers and stretchers, or, as is more often the case, a row of headers every fifth, sixth, or seventh row.1 In the Whitley house the headers in the gable ends are glazed so that a slightly darker pattern, in this case a series of diamonds, stands out clearly. Thus is achieved the effect generally known as ornamental Flemish bond which dates back to eleventh cen- tury Normandy. One of the earliest known examples of this in England is a fourteenth century church at Ashington, Essex, and by the sixteenth century it was widely used for English dwellings.2 Another feature of the Whitley house which never fails to attract attention is the use of dark headers to form the initials of the owner just above the front entrance.3 The idea of brick initials and dates was known in England in the seventeenth cen- tury, one Herfordshire house bearing the inscription, "1648 W F M." One of the earliest American examples was Carthagena in St. -

Federal Courts in the Early Republic: Kentucky 1789-1816 by Mary K. Bonsteel Tachau Woodford L

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 68 | Issue 2 Article 10 1979 Federal Courts in the Early Republic: Kentucky 1789-1816 by Mary K. Bonsteel Tachau Woodford L. Gardner Jr. Redford, Redford & Gardner Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Courts Commons, and the Legal History Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Gardner, Woodford L. Jr. (1979) "Federal Courts in the Early Republic: Kentucky 1789-1816 by Mary K. Bonsteel Tachau," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 68 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol68/iss2/10 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEW FEDERAL COURTS IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC: KENTUCKY 1789-1816. By MARY, K. BONSTEEL TACHAU. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978. Pp. 199, Appendix 29. Price: $16.50 Federal Courts in the Early Republic: Kentucky 1789- 1816 was recognized in June, 1979, by the Kentucky Historical Society as the outstanding contribution in Kentucky history published during the past four years. With the proliferation of books and articles on Kentucky history during that period, it is no small achievement for Professor Tachau's work to have been so honored. The legal profession is the ultimate benefac- tor of a work concerning the early history of the federal courts in Kentucky, a work which necessarily deserves discussion in the legal journals of the state. -

1 Failed Filibusters: the Kemper Rebellion, the Burr Conspiracy And

Failed Filibusters: The Kemper Rebellion, the Burr Conspiracy and Early American Expansion Francis D. Cogliano In January 1803 the Congressional committee which considered the appropriation for the Louisiana Purchase observed baldly, “it must be seen that the possession of New Orleans and the Floridas will not only be required for the convenience of the United States, but will be demanded by their most imperious necessities.”1 The United States claimed that West Florida, which stretched south of the 31st parallel from the Mississippi River in the west to the Apalachicola River in the east (roughly the modern state of Louisiana east of the Mississippi, and the Gulf coasts of Mississippi and Alabama, and the western portion of the Florida panhandle) was included in the Louisiana Purchase, a claim denied by the Spanish. The American claim was spurious but the intent behind it was clear. The United States desired control of West Florida so that the residents of the Mississippi Territory could have access to the Gulf of Mexico. Since the American Revolution the region had been settled by Spaniards, French creoles and Anglo-American loyalists. Beginning in the 1790s thousands of emigrants from the United States migrated to the territory, attracted by a generous system of Spanish land grants. An 1803 American government report described the population around Baton Rouge as “composed partly of Acadians, a very few French, and great majority of Americans.” During the first decade of the nineteenth century West Florida became increasingly unstable. In addition to lawful migrants, the region attracted lawless adventurers, including deserters from the United States army and navy, many of whom fled from the nearby territories of Louisiana and Mississippi.2 1 Annals of Congress, 7th Cong. -

Treason Trial of Aaron Burr Before Chief Justice Marshall

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1942 Treason Trial of Aaron Burr before Chief Justice Marshall Aurelio Albert Porcelli Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Porcelli, Aurelio Albert, "Treason Trial of Aaron Burr before Chief Justice Marshall" (1942). Master's Theses. 687. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/687 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1942 Aurelio Albert Porcelli .TREASON TRilL OF AARON BURR BEFORE CHIEF JUSTICE KA.RSHALL By AURELIO ALBERT PORCELLI A THESIS SUBJfiTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OJ' mE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY .roD 1942 • 0 0 I f E B T S PAGE FOBEW.ARD • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 111 CHAPTER I EARLY LIFE OF llRO:N BURR • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • l II BURR AND JEFF.ERSOB ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 24 III WES!ERN ADVDTURE OF BURR •••••••••••••••••••• 50 IV BURR INDICTED FOR !REASOB •••••••••••••••••••• 75 V !HE TRIAL •.•••••••••••••••• • ••••••••••• • •••• •, 105 VI CHIEF JUSTICE lfA.RSlU.LL AND THE TRIAL ....... .. 130 VII JIA.RSHALJ.- JURIST OR POLITICIAN? ••••••••••••• 142 BIBLIOGRAPHY ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 154 FOREWORD The period during which Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and Aaron Burr were public men was, perhaps, the most interest ing in the history of the United States. -

Ohio County, Kentucky, in the Olden Days

Ohio County, Kentucky, in the Olden Days A series of old newspaper sketches of,,. fragmentary,,. history7 • BY HARRISON D. Ti\YLOR El Prepared for publication in book form by his granddaughter MARY TAYLOR LOGAN With an Introduction by OTTO A. ROTHERT El JOHN P. MORTON & COMPANY INCORPORATED LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY 1926 COPYRIGHT, 1926, BY MARY TAYLOR LOGAN From an oil painting, about 1845 HARRISON D. TAYLOR CONTENTS Introduction ............................ Otto A. Rothert Page I Evidences of Prehistoric People and Early Pioneers . 1 II Old Vienna and Calhoun, Barnett's Station, and Hartford. 6 III Indian Depredations. 10 IV How Stephen Statler Came to Hartford. 15 V First Courts and Courthouse . 19 VI The War of 1812. 28 VII "Ralph Ringwood" . 33 VIII Life in the Olden Days. 35 IX Joseph Barnett and Ignatius Pigman, and Their Land Troubles . 42 X Early Land Titles. 47 XI Forests and Farms. 50 XII The First Hanging. 53 XIII Some Early Merchants. 57 XIV Some Pioneer Families . 64 XV Religion of the Pioneers . 69 XVI Old-Time Schools. 73 XVII Three Early Physicians. 76 XVIII Ten Well-Known Lawyers. 80 XIX Slaves and Slavery. 93 XX Harrison D. Taylor's Autobiographical Notes. 97 XXI History of the Taylor Family. 101 APPENDIX A. Act Forming Ohio County in 1798. 115 B. Ohio County as Recorded by Collins in 1847 and in 1877 117 C. Captain John Ho,vell, Revolutionary Soldier. 125 D. Harrison D. Taylor-A Biographical Sketch. 127 E. Ohio County Biographies Published in 1885. 131 F. Ohio County Marriage Records, 1799 to 1840. 135 Index ............................................ -

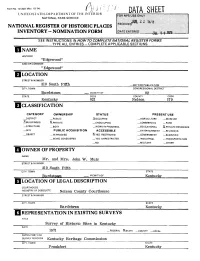

Data Sheet National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) f H ij / - ? • fr ^ • - s - UNITED STATES DHPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DATA SHEET NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC "Edgewood" AND/OR COMMON "Edgewood" STREET & NUMBER 310 South Fifth _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Bardstown —.VICINITY OF 02 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 Nelson 179 UCLA SSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT _ PUBLIC JKOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ZiBUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. and Mrs. John W. Muir STREET & NUMBER 310 South Fifth CITY. TOWN STATE Bardstown VICINITY OF Kentucky LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Nelson County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Kentucky REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Historic Sites in Kentucky DATE 1971 — FEDERAL X STATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Kentucky Heritage Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Frankfort Kentucky DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X.EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Ben Hardin House is a large brick structure located on a sizeable tract of land at the head of Fifth Street in Bardstown. The house consists of two distinct parts, erected at different periods. -

The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 11-15-1994 Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky" (1994). Appalachian Studies. 25. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/25 DAYS OF DARKNESS DAYS OF DARKNESS The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1994 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2010 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1 The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows: Pearce, John Ed. Days of darkness: the feuds of Eastern Kentucky / John Ed Pearce. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8131-1874-3 (hardcover: alk. -

The History of Tippecanoe County Compiled by Quinten Robinson, Tippecanoe County Historian the SETTING Tippecanoe County, Locate

The History of Tippecanoe County Compiled by Quinten Robinson, Tippecanoe County Historian THE SETTING Tippecanoe County, located in west-central Indiana, is about 65 miles northwest of Indianapolis and 100 miles southeast of Chicago. Tippecanoe County is 21 miles east to west and 24 miles north to south and Lafayette, the county seat, is situated on the banks of the Wabash nearly in the center. About one-half the surface consists of broad, fertile, and nearly level plains. The balance consists of gently rolling uplands, steep hillsides or rich alluvial bottoms. Occasional wetlands or bogs are found but those were largely drained by the beginning of the 20th century. The Wabash River flows nearly through the middle of Tippecanoe County from northeast to southwest. Tributaries to the Wabash River that drain the north and west parts of Tippecanoe County are the Tippecanoe River, Burnett Creek, Indian Creek, and Little Pine Creek. Draining the south and east parts of the county are Sugar Creek, Buck Creek, North, South and Middle Forks of the Wildcat Creek, Wea Creek, and Flint Creek. Besides Lafayette, cities and towns in Tippecanoe County are West Lafayette, the home of Purdue University, Battle Ground, West Point, Otterbein, Dayton, Clarks Hill, Romney, Stockwell, Americus, Colburn & Buck Creek. In 2010 county population was set at 172,780 PREHISTORIC TIPPECANOE COUNTY The terrain, the Wabash River, and the creeks you see today in Tippecanoe County came to their present condition about 10,000 years ago as the last continental glacier retreated northward leaving a vastly different landscape than what had existed before the advance of the ice sheets began over 700,000 years ago. -

President Thomas Jefferson V. Chief Justice John Marshall by Amanda

A Thesis Entitled Struggle to Define the Power of the Court: President Thomas Jefferson v. Chief Justice John Marshall By Amanda Dennison Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Master of Arts in History ________________________ Advisor: Diane Britton ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo August 2005 Copyright © 2005 This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. Acknowledgments Finishing this step of my academic career would not have been possible without the support from my mentors, family, and friends. My professors at the University of Toledo have supported me over the past three years and I thank them for their inspiration. I especially thank Professors Alfred Cave, Diane Britton, Ronald Lora, and Charles Glaab for reading my work, making corrections, and serving as advisors on my thesis committee. I am eternally grateful to the University of Toledo History Department for their financial and moral support. When I came to the University of Toledo, I would not have survived my first graduate seminar, let alone long enough to finish this project without the experience from my undergraduate career at Southwestern Oklahoma State University. I thank Professors Laura Endicott and John Hayden for their constant support, reading drafts, and offering suggestions and Professors Roger Bromert and David Hertzel for encouraging me via email and on my visits back to Southwestern. Ya’ll are the best. I have a wonderful support system from my family and friends, especially my parents and brother. Thank you Mom and Dad for your encouragement and love. -

Library of Congress Classification

E AMERICA E America General E11-E29 are reserved for works that are actually comprehensive in scope. A book on travel would only occasionally be classified here; the numbers for the United States, Spanish America, etc., would usually accommodate all works, the choice being determined by the main country or region covered 11 Periodicals. Societies. Collections (serial) For international American Conferences see F1404+ Collections (nonserial). Collected works 12 Several authors 13 Individual authors 14 Dictionaries. Gazetteers. Geographic names General works see E18 History 16 Historiography 16.5 Study and teaching Biography 17 Collective Individual, see country, period, etc. 18 General works Including comprehensive works on America 18.5 Chronology, chronological tables, etc. 18.7 Juvenile works 18.75 General special By period Pre-Columbian period see E51+; E103+ 18.82 1492-1810 Cf. E101+ Discovery and exploration of America Cf. E141+ Earliest accounts of America to 1810 18.83 1810-1900 18.85 1901- 19 Pamphlets, addresses, essays, etc. Including radio programs, pageants, etc. 20 Social life and customs. Civilization. Intellectual life 21 Historic monuments (General) 21.5 Antiquities (Non-Indian) 21.7 Historical geography Description and travel. Views Cf. F851 Pacific coast Cf. G419+ Travels around the world and in several parts of the world including America and other countries Cf. G575+ Polar discoveries Earliest to 1606 see E141+ 1607-1810 see E143 27 1811-1950 27.2 1951-1980 27.5 1981- Elements in the population 29.A1 General works 29.A2-Z Individual elements, A-Z 29.A43 Akan 29.A73 Arabs 29.A75 Asians 29.B35 Basques Blacks see E29.N3 29.B75 British 29.C35 Canary Islanders 1 E AMERICA E General Elements in the population Individual elements, A-Z -- Continued 29.C37 Catalans 29.C5 Chinese 29.C73 Creoles 29.C75 Croats 29.C94 Czechs 29.D25 Danube Swabians 29.E37 East Indians 29.E87 Europeans 29.F8 French 29.G26 Galicians (Spain) 29.G3 Germans 29.H9 Huguenots 29.I74 Irish 29.I8 Italians 29.J3 Japanese 29.J5 Jews 29.K67 Koreans 29.N3 Negroes.