2019 Doña Ana County Historical Society Publisher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Center for Public History

Volume 8 • Number 2 • spriNg 2011 CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY Oil and the Soul of Houston ast fall the Jung Center They measured success not in oil wells discovered, but in L sponsored a series of lectures the dignity of jobs well done, the strength of their families, and called “Energy and the Soul of the high school and even college graduations of their children. Houston.” My friend Beth Rob- They did not, of course, create philanthropic foundations, but ertson persuaded me that I had they did support their churches, unions, fraternal organiza- tions, and above all, their local schools. They contributed their something to say about energy, if own time and energies to the sort of things that built sturdy not Houston’s soul. We agreed to communities. As a boy, the ones that mattered most to me share the stage. were the great youth-league baseball fields our dads built and She reflected on the life of maintained. With their sweat they changed vacant lots into her grandfather, the wildcatter fields of dreams, where they coached us in the nuances of a Hugh Roy Cullen. I followed with thoughts about the life game they loved and in the work ethic needed later in life to of my father, petrochemical plant worker Woodrow Wilson move a step beyond the refineries. Pratt. Together we speculated on how our region’s soul—or My family was part of the mass migration to the facto- at least its spirit—had been shaped by its famous wildcat- ries on the Gulf Coast from East Texas, South Louisiana, ters’ quest for oil and the quest for upward mobility by the the Valley, northern Mexico, and other places too numerous hundreds of thousands of anonymous workers who migrat- to name. -

BERNAL-THESIS-2020.Pdf (5.477Mb)

BROWNWOOD: BAYTOWN’S MOST HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOOD by Laura Bernal A thesis submitted to the History Department, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Chair of Committee: Dr. Monica Perales Committee Member: Dr. Mark Goldberg Committee Member: Dr. Kristin Wintersteen University of Houston May 2020 Copyright 2020, Laura Bernal “A land without ruins is a land without memories – a land without memories is a land without history.” -Father Abram Joseph Ryan, “A Land Without Ruins” iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, and foremost, I want to thank God for guiding me on this journey. Thank you to my family for their unwavering support, especially to my parents and sisters. Thank you for listening to me every time I needed to work out an idea and for staying up late with me as I worked on this project. More importantly, thank you for accompanying me to the Baytown Nature Center hoping to find more house foundations. I am very grateful to the professors who helped me. Dr. Monica Perales, my advisor, thank you for your patience and your guidance as I worked on this project. Thank you to my defense committee, Dr. Kristin Wintersteen and Dr. Goldberg. Your advice helped make this my best work. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Debbie Harwell, who encouraged me to pursue this project, even when I doubted it its impact. Thank you to the friends and co-workers who listened to my opinions and encouraged me to not give up. Lastly, I would like to thank the people I interviewed. -

Explosive Weapon Effectsweapon Overview Effects

CHARACTERISATION OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS EXPLOSIVEEXPLOSIVE WEAPON EFFECTSWEAPON OVERVIEW EFFECTS FINAL REPORT ABOUT THE GICHD AND THE PROJECT The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) is an expert organisation working to reduce the impact of mines, cluster munitions and other explosive hazards, in close partnership with states, the UN and other human security actors. Based at the Maison de la paix in Geneva, the GICHD employs around 55 staff from over 15 countries with unique expertise and knowledge. Our work is made possible by core contributions, project funding and in-kind support from more than 20 governments and organisations. Motivated by its strategic goal to improve human security and equipped with subject expertise in explosive hazards, the GICHD launched a research project to characterise explosive weapons. The GICHD perceives the debate on explosive weapons in populated areas (EWIPA) as an important humanitarian issue. The aim of this research into explosive weapons characteristics and their immediate, destructive effects on humans and structures, is to help inform the ongoing discussions on EWIPA, intended to reduce harm to civilians. The intention of the research is not to discuss the moral, political or legal implications of using explosive weapon systems in populated areas, but to examine their characteristics, effects and use from a technical perspective. The research project started in January 2015 and was guided and advised by a group of 18 international experts dealing with weapons-related research and practitioners who address the implications of explosive weapons in the humanitarian, policy, advocacy and legal fields. This report and its annexes integrate the research efforts of the characterisation of explosive weapons (CEW) project in 2015-2016 and make reference to key information sources in this domain. -

ASME National Historical Mechanical Engineering Landmark Program 1975

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC U.S.S. Texas AND/OR COMM Battleship Texas LOCATION -T& NUMBER San Jacinto Battleground State Park STREETea. &NUr "2? mi. east of Houston on Tex. 13* _NOTFORPUBL1CAT10N CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF Houston STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Texas Harris 201 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —XPUBLIC .XOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _ PARK' —STRUCTURE . —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS .XEDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS ^•.OBJECT _IN PROCESS .XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT -^SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY Contact: C.H. Taylor, Chairman NAME State of Texas, The Battleship Texas Commission STREET & NUMBER EXXON Building; Suite 2695 CITY, TOWN STATE Houston VICINITY OF Texas LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. The Battleship Texas Commission STREET & NUMBER EXXON Building. Suite 26QR CITY, TOWN STATE Houston Texas REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE ASME National Historical Mechanical Engineering Landmark Program DATE 1975 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS ASME United Engineering Center CITY. TOWN New York DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE X_GOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED X_MOVED DATE 1948 —FAIR — UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company built Texas (BB35) in 1911-14. Upon her completion she measured 573 feet long, was 94 3/4 feet wide at the beam, had a normal displacement of 27,000 tons and a mean draft of 28 1/2 feet, and boasted a top speed of 21 knots. -

Merle A. Tuve

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES M E R L E A N T O N Y T UVE 1901—1982 A Biographical Memoir by P H ILI P H . AbELSON Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1996 NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS WASHINGTON D.C. MERLE ANTONY TUVE June 27, 1901–May 20, 1982 BY PHILIP H. ABELSON ERLE ANTONY TUVE WAS a leading scientist of his times. MHe joined with Gregory Breit in the first use of pulsed radio waves in the measurement of layers in the ionosphere. Together with Lawrence R. Hafstad and Norman P. Heydenburg he made the first and definitive measurements of the proton-proton force at nuclear distances. During World War II he led in the development of the proximity fuze that stopped the buzz bomb attack on London, played a crucial part in the Battle of the Bulge, and enabled naval ships to ward off Japanese aircraft in the western Pacific. Following World War II he served for twenty years as director of the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Department of Ter- restrial Magnetism, where, in addition to supporting a mul- tifaceted program of research, he personally made impor- tant contributions to experimental seismology, radio astronomy, and optical astronomy. Tuve was a dreamer and an achiever, but he was more than that. He was a man of conscience and ideals. Throughout his life he remained a scientist whose primary motivation was the search for knowledge but a person whose zeal was tempered by a regard for the aspirations of other humans. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 250/Tuesday, December 31, 2019

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 250 / Tuesday, December 31, 2019 / Notices 72339 (vii) Date Report Delivered to ACTION: Arms sales notice. House of Representatives, Transmittal Congress: December 4, 2019 18–39 with attached Policy Justification [FR Doc. 2019–28189 Filed 12–30–19; 8:45 am] SUMMARY: The Department of Defense is and Sensitivity of Technology. publishing the unclassified text of an BILLING CODE 5001–06–P Dated: December 23, 2019. arms sales notification. Aaron T. Siegel, FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Alternate OSD Federal Register Liaison DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE Karma Job at [email protected] Officer, Department of Defense. or (703) 697–8976. Office of the Secretary BILLING CODE 5001–06–P SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: This [Transmittal No. 18–39] 36(b)(1) arms sales notification is Arms Sales Notification published to fulfill the requirements of section 155 of Public Law 104–164 AGENCY: Defense Security Cooperation dated July 21, 1996. The following is a Agency, Department of Defense. copy of a letter to the Speaker of the VerDate Sep<11>2014 17:30 Dec 30, 2019 Jkt 250001 PO 00000 Frm 00048 Fmt 4703 Sfmt 4703 E:\FR\FM\31DEN1.SGM 31DEN1 khammond on DSKJM1Z7X2PROD with NOTICES 72340 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 250 / Tuesday, December 31, 2019 / Notices BILLING CODE 5001–06–C Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain and Major Defense Equipment (MDE): Transmittal No. 18-39 the United Kingdom Five hundred (500) KMU-556 F/B Joint Notice of Proposed Issuance of Letter of (ii) Total Estimated Value: Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) Kits for GBU-31 2000-lbs Offer Pursuant to Section 36(b)(1) of the Major Defense Equip- $240.5 million ment *. -

2016 Summer the Medallion

SUMMER 2016 Waco’ s Awakening Burgeoning Brazos Trail City A New Hot Spot for Cultural Tourism CONTENTS SUMMER 2016 TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION John L. Nau, III, Chair John W. Crain, Vice Chair THC OUTREACH Robert K. Shepard, Secretary 10 History Afloat East Texas Paddling Earl Broussard, Jr. Trail Lets Visitors Float Thomas M. Hatfield Through the Past. Wallace B. Jefferson Tom Perini Gilbert E. “Pete” Peterson Judy C. Richardson 11 Cemetery Queries Daisy Sloan White Three Frequently Asked Questions Answered by THC Staff. Executive Director: Mark Wolfe FEATURE Medallion Staff: 6 Waco’s Awakening Chris Florance Burgeoning Brazos Trail Division Director City a New Hot Spot Andy Rhodes Managing Editor for Cultural Tourism. Judy Jensen Senior Graphic Design Coordinator ISSN 0890-7595 Vol. 54, No. III thc.texas.gov [email protected] ON THE COVER: Waco’s historic suspension bridge. Photo: Andy Rhodes. VISIT US ON THE WEB FAST FACTS thc.texas.gov These numbers show the significant economic impact Learn more about the real places telling the real stories of Texas. of cultural travel in Waco. texastimetravel.com The Texas Heritage Trails Program’s travel resource texashistoricsites.com 1.3 6,300 $26.4 The THC’s 20 state historic properties thcfriends.org MILLION VISITORS JOBS SUPPORTED MILLION VISITOR Friends of the Texas Historical Commission ANNUALLY TO WACO’S BY WACO TOURISM CONTRIBUTION TO WACO’S SILO DISTRICT STATE TAX REVENUE Source: Waco Convention & Visitors Bureau TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION thc.texas.gov 2 LEADERSHIP LETTER My Fellow Texans, Senate District 22 in the heart of Texas is a perfect microcosm of our state: part rural, part suburban, part urban. -

Texas Public Safety Threat Overview 2013 (PDF)

UNCLASSIFIED Texas Public Safety Threat Overview 2013 Texas Public Safety Threat Overview 2013 A State Intelligence Estimate Produced by the Texas Department of Public Safety In collaboration with other law enforcement and homeland security agencies February 2013 1 UNCLASSIFIED Texas Public Safety Threat Overview 2013 Executive Summary (U) Texas faces the full spectrum of threats, and the state’s vast size, geography, and large population present unique challenges to public safety and homeland security. Texas employs a systematic approach to detect, assess, and prioritize public safety threats within seven categories: crime, terrorism, motor vehicle crashes, natural disasters, public health threats, industrial accidents and cyber threats. (U) Crime threatens the safety, security and freedom of people. Sadly, one needs only to look to our neighbor to the south to view the impact that organized crime can have on a nation and its citizens. Some 60,000 men and woman have been killed in Mexico since 2006, with a substantial number of brutal tortures and beheadings. (U) Index crimes measured by the Uniform Crime Reporting system have decreased throughout Texas and the nation, which is encouraging, as the eight index crimes include homicide, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, larceny, and arson. These are referred to as index crimes because they were selected in the 1930s to provide an index of the general level of criminal activity. From 2010 to 2011, the most recent year for which complete data is available, the volume of index crimes in Texas declined 6.4 percent and the crime rate declined 8.3 percent. -

Hispanic Texans

texas historical commission Hispanic texans Journey from e mpire to Democracy a GuiDe for h eritaGe travelers Hispanic, spanisH, spanisH american, mexican, mexican american, mexicano, Latino, Chicano, tejano— all have been valid terms for Texans who traced their roots to the Iberian Peninsula or Mexico. In the last 50 years, cultural identity has become even more complicated. The arrival of Cubans in the early 1960s, Puerto Ricans in the 1970s, and Central Americans in the 1980s has made for increasing diversity of the state’s Hispanic, or Latino, population. However, the Mexican branch of the Hispanic family, combining Native, European, and African elements, has left the deepest imprint on the Lone Star State. The state’s name—pronounced Tay-hahs in Spanish— derives from the old Spanish spelling of a Caddo word for friend. Since the state was named Tejas by the Spaniards, it’s not surprising that many of its most important geographic features and locations also have Spanish names. Major Texas waterways from the Sabine River to the Rio Grande were named, or renamed, by Spanish explorers and Franciscan missionaries. Although the story of Texas stretches back millennia into prehistory, its history begins with the arrival of Spanish in the last 50 years, conquistadors in the early 16th cultural identity century. Cabeza de Vaca and his has become even companions in the 1520s and more complicated. 1530s were followed by the expeditions of Coronado and De Soto in the early 1540s. In 1598, Juan de Oñate, on his way to conquer the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, crossed the Rio Grande in the El Paso area. -

A History of the National Bureau of Standards

WORLD WAR Ii RESEARCH (1941-45) CHAPTER 'TI! ThE EVENT OF WAR" The second worldwide war was foreshadowed in the Japanese in of Ethiopia in 1935, and Hitler's march into the Rhineland in 1936. Isolated and safeguarded by successive Neutrality Acts passed in 1935, 1936, and 1937, which barred the sale of arms or munitions to any warring nation, America watched the piecemeal fall of small nations, Austria and Czechoslovakia to Hitler, Albania to Musso- lini. With the German attack on Poland in September 1939, Britain and France declared war against the dictators and World War II began. The first amendments to the Neutrality Acts were enacted. By temperament strongly neutral and still in the grip of depression, the Nation had willed belief in Chamberlain's "peace in our time" until shaken by the occupation of Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939. But cer- tain of war and of America's inevitable involvement was the small band of foreign-born scientists, their spokesman Niels Bohr, who had recently arrived in this country. Shepherding atomic research here, Bohn at once urged restriction in all Allied countries of the publication of further data on the possibility of nuclear fission. Many individual scientists refrained, but control of publication in American scientific journals did not become effec. five until almost a year later, following Hitler's invasion of Denmark and Norway. The National Bureau of Standards, convinced by the physicists on its Advisory Committee on Uranium of the certainty of a general war, began to put its affairs in order. On September 1, 1939, the day Germany marched into Poland, and one week before the President declared a state of limited national emergency, Dr. -

In Defense of Freedom-The Early Years

WALTER G. BERL IN DEFENSE OF FREEDOM - THE EARLY YEARS This article describes the events that led to the founding of the Applied Physics Laboratory. It summarizes the development of a novel fuze for rotating antiaircraft ammunition and the organization that achieved it, continues with a discussion of the early stages of the development of a new technology for the delivery of warheads-the guided missile, and concludes with a brief sketch of Merle A. Tuve' s career that led to his involvement with these programs. INTRODUCTION On 11 September 1939, only ten days after the German days from near the city to the Channel coast where they army invaded Poland and World War II began, President could function more effectively) and proximity-fuzed Franklin D. Roosevelt sent the first of many notes to shells were deployed for the first time in the European Winston Churchill in which he proposed that Churchill theater, only one in twenty of the flying bombs succeeded reply with "anything you may want me to know about."! in their mission. In early September, the V-I launching One such message, No. 831, from Churchill to President sites were captured by the advancing Allied forces and Roosevelt, dated 26 November 1944, read: the V-I attacks ceased.2 Halfway around the world, in the Pacific, a similar Cherwell [Churchill's Science Advisor] has told me how very drama was unfolding. In October 1944, strong American kind the US Army and Navy were in showing him their latest developments in many fields .... Perhaps, if you thought it forces appeared in the Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. -

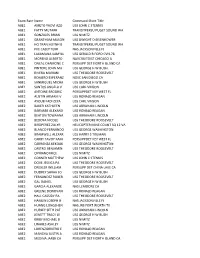

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE